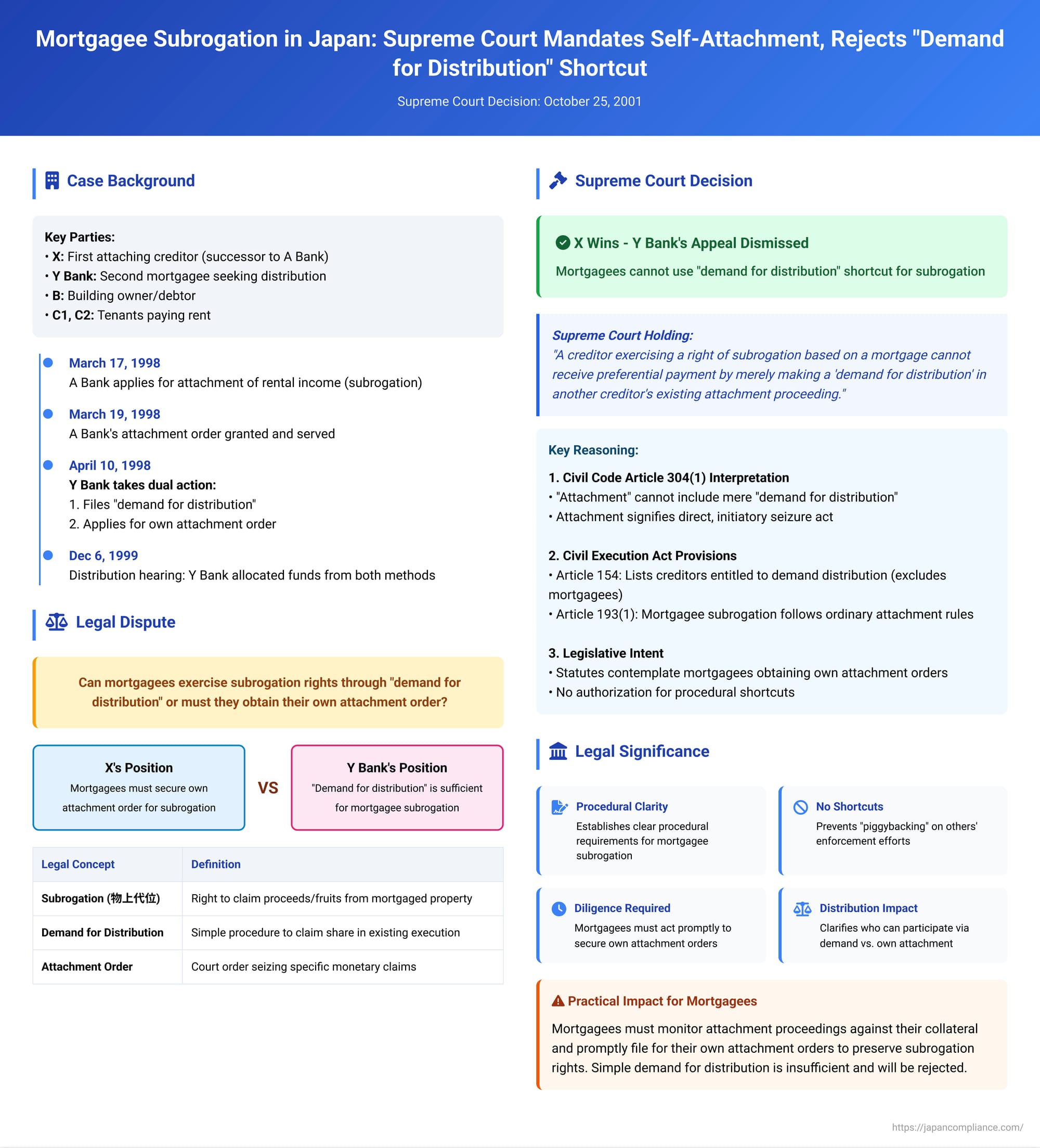

Mortgagee Subrogation in Japan: Supreme Court Mandates Self-Attachment, Rejects "Demand for Distribution" Shortcut

Date of Supreme Court Decision: October 25, 2001

In the intricate dance of creditor claims against a common debtor, Japanese law provides various mechanisms for enforcement. For mortgagees seeking to claim rental income from a mortgaged property under their right of subrogation (物上代位 - butsujō daii), a pivotal question has been the precise procedural path required, especially when another creditor has already initiated attachment proceedings against that same income. A definitive answer came from the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on October 25, 2001 (Heisei 13 (Ju) No. 91), which ruled that mortgagees must secure their own attachment order and cannot simply opt for the potentially quicker route of filing a "demand for distribution" (配当要求 - haitō yōkyū) in the existing proceedings.

The Factual Scenario: Competing Claims on Rental Income

The case involved multiple parties vying for rental income generated by a building owned by B:

- Initial Attachment by A Bank (X's Predecessor): On March 17, 1998, A Bank, holding a neteitōken (a type of revolving mortgage) on B's building, initiated proceedings to exercise its right of subrogation over the rental income due to B from tenants C1 and C2. A Bank applied for and, on March 19, 1998, was granted a債権差押命令 (saiken sashiosae meirei – an order for the attachment of a monetary claim, hereinafter "attachment order"). This order was subsequently served on the tenants. (The plaintiff X later succeeded to A Bank's position after a series of assignments and a merger).

- Y Bank's Actions (Another Mortgagee): Y Bank also held a neteitōken on the same building, with the same priority ranking as A Bank's. On April 10, 1998, Y Bank took two steps concerning the rental income already targeted by A Bank's attachment:

- It filed a "demand for distribution" (haitō yōkyū) with the court in A Bank’s existing attachment case, asserting its own right of subrogation under its mortgage. A demand for distribution is typically a simpler procedure for a creditor to stake a claim to funds being collected through another creditor's execution efforts.

- Separately, Y Bank also applied for and obtained its own attachment order against the same rental income, likewise based on its right of subrogation.

- Deposit and Distribution Plan: Following service of A Bank's attachment order, the tenants (C1 and C2) deposited the rental income with the court. The execution court initially (on March 23, 1999) rejected Y Bank's demand for distribution. However, Y Bank successfully appealed this rejection, and an appellate court decision allowed its demand for distribution to proceed. Subsequently, on December 6, 1999, a distribution hearing was held. The proposed distribution plan allocated specific amounts to the creditors:

- Approximately ¥21.91 million to X (as successor to A Bank, based on the initial attachment order).

- Approximately ¥7.10 million to Y Bank, specifically based on its demand for distribution.

- Approximately ¥3.86 million to Y Bank, based on its own separate attachment order.

- X's Objection: X, the successor to the first attaching creditor, objected to the ¥7.10 million portion allocated to Y Bank that stemmed from Y Bank's demand for distribution. X contended that a mortgagee exercising its right of subrogation over rental income cannot validly do so by merely filing a demand for distribution; instead, it must secure its own attachment order.

The Legal Question: A Proper Path for Mortgagee Subrogation?

The central legal issue before the Supreme Court was whether a "demand for distribution" is a permissible and effective method for a mortgagee to exercise its right of subrogation over rental income that is already the subject of an attachment by another creditor, or whether the mortgagee is obligated to obtain its own, separate attachment order to assert such rights.

The Tokyo District Court (the court of first instance for X's objection suit) had dismissed X's claim, finding no compelling reason to differentiate the procedural requirements for mortgagees from those applicable to statutory lien holders (for whom prior case law had hinted that a demand for distribution might suffice). However, the Tokyo High Court (second instance) reversed this, siding with X. The High Court held that, unlike statutory liens, mortgagees exercising subrogation must obtain their own attachment order and cannot rely on a mere demand for distribution. Y Bank appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Attachment is Indispensable for Mortgagee Subrogation

The Supreme Court, in its ruling of October 25, 2001, upheld the Tokyo High Court's decision and dismissed Y Bank's appeal. The Court definitively stated that a creditor exercising a right of subrogation based on a mortgage cannot receive preferential payment by merely making a "demand for distribution" in another creditor's existing attachment proceeding.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was grounded in a careful interpretation of the relevant provisions of the Civil Code and the Civil Execution Act:

- Interpretation of Civil Code Article 304(1) (applied to mortgages via Article 372):

Article 304, Paragraph 1, proviso of the Civil Code stipulates that a secured creditor (including a mortgagee exercising subrogation) must "attach" (差し押える - sashiosaeru) the proceeds (such as rent) before these proceeds are paid or delivered to the debtor. The Supreme Court held that the term "attachment" in this context cannot be construed to include a mere "demand for distribution." The act of "attachment" signifies a more direct, initiatory act of seizure by the subrogating creditor against the specific claim. - Provisions of the Civil Execution Act:

The Court then examined the relevant articles of the Civil Execution Act:The Supreme Court concluded that these statutory provisions, when read together, do not contemplate or authorize a mortgagee exercising its right of subrogation to do so through the procedural shortcut of a demand for distribution. The legislatively intended path is for the mortgagee to secure its own attachment order against the specific proceeds.- Article 154 (Creditors Entitled to Demand Distribution): This article enumerates the types of creditors who are explicitly authorized to make a demand for distribution in an ongoing execution proceeding against a monetary claim. These typically include creditors holding an enforceable title (like a final judgment) and certain types of statutory lien holders. The Court noted that this provision does not explicitly include mortgagees exercising a right of subrogation.

- Article 193, Paragraph 1 (Execution of Security Interests over Claims): This article governs the procedure for enforcing security interests (which encompasses a mortgagee's right of subrogation over a claim like rent). It generally provides that such enforcement should follow the rules applicable to the ordinary attachment of monetary claims. This implies that the mortgagee should apply for and obtain its own attachment order, providing documents evidencing its security interest.

Distinguishing Mortgages from Statutory Liens

An underlying element of the discussion, as reflected in legal commentary and the lower court proceedings, was the potential distinction between mortgagees and holders of statutory liens (先取特権 - sakidori tokken). Some earlier Supreme Court cases had contained obiter dicta (non-binding judicial remarks) that seemed to suggest that statutory lien holders exercising subrogation might be able to utilize a demand for distribution. This naturally led to arguments that mortgagees should be treated similarly.

However, the Supreme Court's 2001 decision drew a clear line, at least concerning mortgagees. While the judgment itself does not extensively delve into the policy reasons for distinguishing between the two types of security interests in this procedural context, legal scholars have pointed to several factors that might justify different treatment:

- Nature of the Security Right: Mortgages are typically consensual security interests created by contract and made public through registration. Statutory liens, on the other hand, often arise automatically by operation of law to protect specific classes of claims deemed to warrant special protection (e.g., employee wages, funeral expenses, claims of sellers of movable goods). The creditors in the latter category may not have had the same opportunity to negotiate for and formally register a security interest.

- Ease of Enforcement for Mortgagees: Mortgagees, by definition, have their rights documented through a public registration (the mortgage deed). This readily available proof makes it relatively straightforward for them to apply for and obtain their own attachment order when seeking to exercise subrogation over proceeds. The argument is that they may not require the same procedural leniency or shortcuts that might arguably be extended to certain statutory lien holders whose rights might be less formally documented or who might face greater hurdles in initiating full attachment proceedings.

Practical Implications of the Ruling

The Supreme Court's decision has several important practical consequences for mortgagees and the conduct of civil execution in Japan:

- Mortgagees Must Initiate Their Own Attachment: The most direct implication is that mortgagees wishing to exercise their right of subrogation over proceeds (like rental income) that are already the subject of an attachment by another creditor must file for and obtain their own, separate attachment order. They cannot rely on the simpler and potentially quicker procedure of merely filing a demand for distribution in the existing attachment case.

- No "Piggybacking" on Others' Efforts: This ruling prevents mortgagees from simply "piggybacking" on the enforcement efforts of another attaching creditor by using the demand for distribution mechanism to assert their subrogation rights. Each mortgagee wanting to claim such proceeds must take the formal step of initiating its own attachment.

- Procedural Diligence Required: Mortgagees need to be procedurally diligent. If they become aware that rental income or other proceeds from their mortgaged property are being attached by other creditors, they must act promptly to secure their own attachment order if they intend to claim those proceeds via subrogation. Delay could result in the proceeds being distributed without their priority being recognized if they haven't taken the correct procedural steps.

- Impact on Distribution Proceedings: The decision clarifies who is entitled to participate in distribution via a demand for distribution versus who must secure their own attachment. This affects how execution courts will process claims and prepare distribution statements. Y Bank, in this case, was ultimately only entitled to a share based on its own attachment order, not on its disallowed demand for distribution.

- Ongoing Discussion for Statutory Liens: While this judgment is definitive for mortgagees, it has fueled further academic discussion on whether the Supreme Court might, in the future, extend a similar restrictive interpretation (requiring self-attachment) to statutory lien holders, potentially reconsidering the earlier, more lenient hints. This aspect of the law continues to be an area of interest for legal commentators.

The commentary also noted a specific factual nuance in this case: the first attaching creditor, A Bank, had reportedly initiated its attachment somewhat unexpectedly, at a time when Y Bank might have been under the impression that tenants were making voluntary pro rata payments to the creditors. This might have placed Y Bank in a difficult position to react swiftly with its own full attachment. However, the Supreme Court’s decision was based on a broader interpretation of the applicable laws, not on the specific equities of this particular sequence of events for Y Bank.

Concluding Thoughts

The October 25, 2001, Supreme Court decision delivers a clear and unequivocal message to mortgagees in Japan: when exercising the right of subrogation over monetary proceeds like rental income that are already subject to another creditor's attachment, obtaining a separate, self-initiated attachment order is indispensable. The simpler path of filing a "demand for distribution" in the pre-existing attachment proceeding is not a valid method for mortgagees to assert these specific rights. This ruling emphasizes the importance of adhering to distinct procedural requirements for different types of creditors and security interests within the framework of Japanese civil execution law, ensuring that the potent right of mortgage subrogation is exercised through a formal and specific judicial process. It underscores the principle that while substantive rights are foundational, the procedural mechanisms for their enforcement must be correctly navigated.