Mortgaged Building, Leased Land: Does the Land Lease Transfer with the Building in Japan?

Date of Judgment: May 4, 1965

Case Name: Claim for Removal of Building and Vacant Possession of Land

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

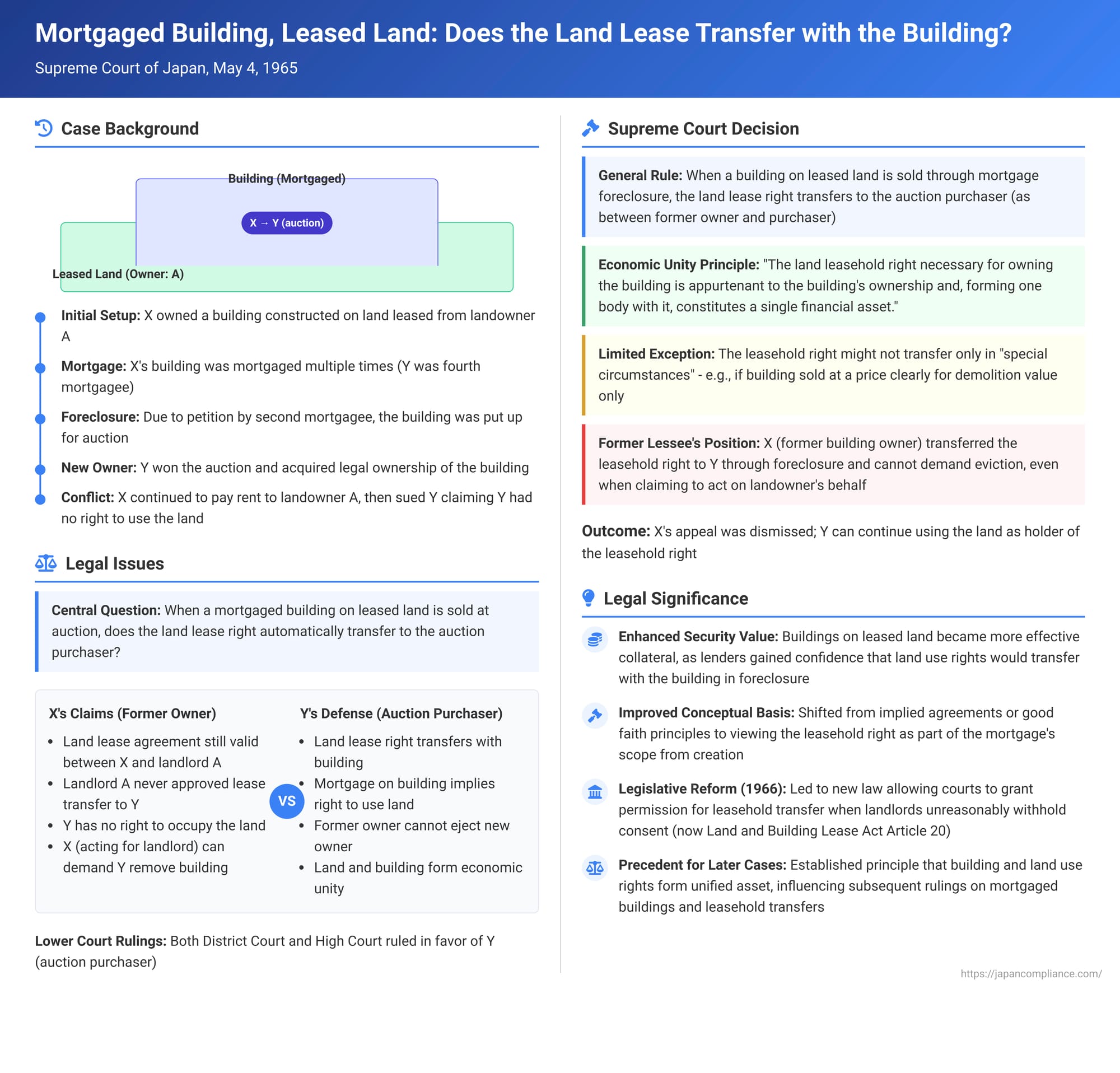

In Japan, it's common for buildings to be constructed on land leased from another party. This arrangement raises a critical legal question when the building owner mortgages the building: if the mortgage is foreclosed and the building sold, what happens to the underlying land lease right (shakuchi-ken)? Does the auction purchaser of the building also acquire the right to use the land, or can the original lessee (the mortgagor) or the landowner interfere with the purchaser's use of the land? A landmark Supreme Court of Japan judgment on May 4, 1965, provided significant clarification on this issue, establishing that the land lease right generally transfers with the mortgaged building.

The Factual Matrix: A Foreclosure and a Determined Former Owner

The case involved X, who owned a building (the "Building") that she had constructed on land (the "Land") leased from landowner A for the purpose of building ownership.

- X had taken out several mortgages on the Building. The fourth mortgage was held by Y.

- Due to a petition by C (the second mortgagee), the Building was put up for a mortgage foreclosure auction. Y, the fourth mortgagee, emerged as the successful bidder and legally acquired ownership of the Building.

- Despite Y's acquisition of the Building, X continued to pay rent for the Land to the landowner, A. A, in turn, continued to recognize X as the legitimate lessee of the Land and had not given consent for X's land leasehold right to be transferred or subleased to Y, the new building owner.

- In a somewhat unusual legal maneuver, X (the former building owner and original lessee of the land) filed a lawsuit against Y (the new building owner). X sued "by way of subrogation for the landowner A" (A ni daii shite), demanding that Y remove the Building from the Land and return vacant possession of the Land.

X's argument was that since her lease agreement with A for the Land was still ongoing, and A had not approved any lease transfer to Y, Y had no right to occupy the Land from A's perspective. X claimed that if A did not directly sue Y, Y would be able to use the Land indefinitely without right or payment, creating a disorderly situation.

Y countered that when a building on leased land is mortgaged, it is implied that the land lease right will also be transferred or subleased to any auction purchaser if the mortgage is foreclosed. Therefore, Y argued, X could not demand Y's eviction, even by purporting to act on behalf of the landowner.

The District Court and the High Court both ruled in favor of Y, dismissing X's claim. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling (May 4, 1965)

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, affirming the lower courts' decisions that X could not evict Y. The Court's reasoning established a crucial principle:

- Land Leasehold Right Generally Transfers with the Building: The Court held that when a building owned by a land lessee is sold through a mortgage foreclosure auction, and the auction purchaser acquires ownership of that building, the land leasehold right necessary for the ownership and use of that building also transfers to the auction purchaser, as between the former building owner (mortgagor) and the auction purchaser. This general rule applies unless there are "special circumstances," such as the building being sold at a price that clearly presupposes its imminent demolition. (The Supreme Court noted that the High Court had also considered the possibility of a sublease relationship arising between X and Y, a view the Supreme Court itself did not adopt, but it stated this particular difference in reasoning did not affect the ultimate outcome of the case.)

- Rationale – Economic Unity of Building and Land Use Right: The Court's core rationale was the inherent link between the building and the right to use the land it sits on: "The land leasehold right necessary for owning the building is appurtenant to the said building's ownership and, forming one body with it, constitutes a single financial asset. Therefore, when a mortgage is created on the building, the land leasehold right should, in principle, be construed as being included within the scope of the objects to which the mortgage's effect extends."

- Position of the Former Lessee (X): Given this principle, the Supreme Court concluded that X, the former owner of the Building, had, through the mortgage foreclosure process, effectively transferred her land leasehold right to Y along with the Building. Consequently, X could not subsequently, by purporting to subrogate for the landowner A, demand that Y vacate the Land. The landowner A's lack of consent to the transfer of the leasehold right to Y was a separate issue concerning Y's ability to assert the leasehold against A, but it did not give X (the former lessee) grounds to evict Y.

- Burden of Proof for "Special Circumstances": The Court also clarified that the burden of proving any "special circumstances" (e.g., that the building was sold for demolition value only, implying the leasehold was not intended to transfer) rested on X, the former building owner. X had not met this burden.

The "Scope of Mortgage" Doctrine for Leased Land Rights

This 1965 judgment was significant because it provided a clearer and more robust legal basis for the transfer of land use rights with a mortgaged building than previous case law had offered. Earlier decisions by the Great Court of Cassation (Japan's highest court before the post-WWII system) had also affirmed the transfer of such rights but had often relied on more tenuous grounds, such as inferring an implied agreement between the mortgagor and the auction purchaser to transfer the leasehold, or invoking principles of good faith.

The Supreme Court, in this case, shifted the focus from the presumed intentions at the time of auction to the objective scope of the mortgage at the time of its creation. By reasoning that the land leasehold right forms an economic unity with the building and is thus encompassed by the mortgage on the building, the Court treated the leasehold right as part of the mortgage security from the outset. This approach is considered superior because it means that upon foreclosure, the issue is a direct transfer of the leasehold right, rather than the creation of a new sublease (which would keep the original lessee involved in the land use relationship). Furthermore, at the time of this judgment, Japanese law generally did not permit the direct creation of a mortgage over a leasehold right itself (as distinct from a mortgage over the building). Treating the leasehold right as falling within the scope of the building's mortgage was therefore a practically necessary interpretation to allow such rights to be effectively included in the security package.

While the judgment does not explicitly state whether its reasoning is based on an analogy to Civil Code Article 87, Paragraph 2 (which states that an "appurtenance" follows the disposition of the "principal thing") or Article 370 (which defines the scope of a mortgage on an immovable), its emphasis on the leasehold right being "appurtenant" to the building and forming "one financial asset" with it strongly aligns with the concept of an accessory right that follows the principal. The prevailing academic theory at the time also supported the idea that the site utilization right was an "accessory right" to the building, often invoking Article 87(2) by analogy.

Implications and Benefits of this Rule

The principle established by this judgment has several important benefits:

- Enhanced Security Value of Buildings on Leased Land: It allows buildings on leased land to be used more effectively as collateral for loans. Lenders can have greater confidence that if they foreclose on the building, the essential right to keep the building on the land will also pass to the purchaser, preserving the building's value as an ongoing concern rather than just its demolition value.

- Simplified Enforcement: By including the value of the land lease right within the scope of the building mortgage, it simplifies the enforcement process. Execution courts do not need to undertake complex valuations to try and separate the value of the leasehold from the value of the building itself when distributing auction proceeds. The mortgagee has a priority claim over the entire proceeds representing the unified asset.

The Landowner's Consent Dilemma (Civil Code Article 612)

Despite the Supreme Court's clarification that the leasehold right transfers from the former lessee to the auction purchaser, a significant practical issue remained: Article 612, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code requires a lessee to obtain the lessor's (landowner's) consent to assign the leasehold right or to sublet the leased property. Without such consent, the assignee (the auction purchaser, in this context) cannot assert the leasehold right against the non-consenting landowner. The landowner could still potentially demand that the auction purchaser remove the building from the land.

If this were the end of the matter, the auction purchaser, despite "acquiring" the leasehold right from the former lessee, would be in a precarious position. They might only be able to recover the building's market value by exercising a statutory right (under then Land Lease Act Article 10, now Land and Building Lease Act Article 13) to demand that the landowner purchase the building if the lease is terminated due to refusal of consent for transfer. The valuable leasehold right itself could be lost without compensation, which would severely undermine the utility of mortgaging buildings on leased land.

Legislative Solution: Permission in Lieu of Consent

Recognizing this problem, the Japanese Diet enacted legislation shortly after this Supreme Court judgment (Act No. 93 of 1966), which introduced Article 9-3 into the old Land Lease Act (this provision was later succeeded by Article 20 of the current Land and Building Lease Act). This crucial legislative reform provides that if a building on leased land is acquired by a third party through an auction or public sale, and the landowner refuses to consent to the transfer of the land leasehold right to that third party, even though the transfer would cause no disadvantage to the landowner, the court may, upon the application of the third party (the auction purchaser), grant permission for the transfer in lieu of the landowner's consent.

This legislative measure was a vital complement to the Supreme Court's 1965 ruling. It effectively ensures that the transfer of the land leasehold right with the building upon mortgage foreclosure can be made fully effective against the landowner, provided there is no genuine prejudice to the landowner's interests. This significantly strengthened the legal framework for using buildings on leased land as security.

Post-1965 Developments

Later Supreme Court cases built upon the principles established in 1965. For instance, a judgment on March 11, 1977, clarified the situation where a lessee-mortgagor transfers the land leasehold right to a third party (with the landowner's consent) before the mortgage on the building is foreclosed. The Court held that the third-party assignee of the leasehold acquires it subject to the pre-existing mortgage on the building (which, as per the 1965 ruling, implicitly covers the leasehold right). If the building mortgage is subsequently foreclosed, the auction purchaser who acquires the building and the associated leasehold right will prevail over this third-party assignee. The assignee loses their leasehold right first against the auction purchaser, and then, once the auction purchaser obtains the landowner's consent (or court permission in lieu thereof), they also lose their status as lessee vis-à-vis the landowner, effectively exiting the lease relationship without a claim for damages against the landowner for this ousting.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of May 4, 1965, was a pivotal moment in Japanese property and mortgage law. By establishing that a mortgage on a building constructed on leased land generally extends its effect to include the essential land leasehold right, the Court recognized the economic reality of these combined assets and enhanced their viability as security. This principle, that the building and its site utilization right are treated as a unified whole in foreclosure, supported by subsequent legislative measures allowing courts to substitute permission for a landowner's unreasonably withheld consent, has created a more stable and predictable legal environment for financing and transactions involving buildings on leased land in Japan.