Mortgage vs. Assignment: Japanese Supreme Court on Priority Over Rental Income

Date of Judgment: January 30, 1998

Case Name: Claim for Collection of Attached Claim

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

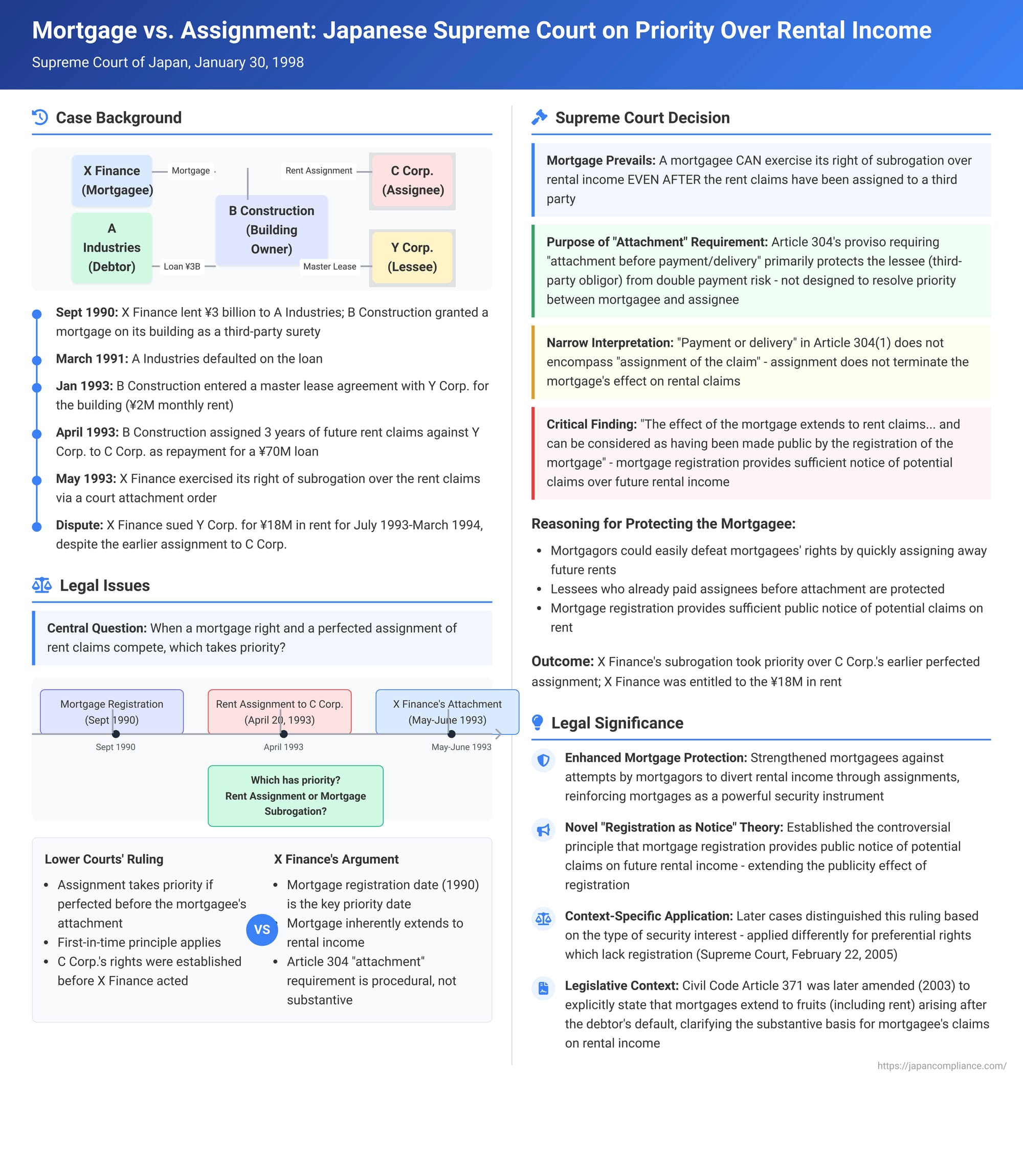

When a property is mortgaged, the lender (mortgagee) typically looks to the property's capital value as security. However, if the mortgaged property generates rental income, can the mortgagee also claim these rents, especially if the mortgagor defaults? This right, known as "subrogation over property" (butsujō daii), allows a mortgagee to pursue certain proceeds or substitutes derived from the mortgaged asset. A critical question arises when the mortgagor assigns future rental income to another party before the mortgagee attempts to exercise this right of subrogation. Which right takes precedence: the assignee's perfected right to the rent, or the mortgagee's subsequent attempt to claim it via subrogation? The Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark judgment on this contentious issue on January 30, 1998.

The Factual Tangle: A Loan, A Mortgage, Leases, and a Rent Assignment

The case involved a complex web of financial arrangements and property rights:

- The Loan and Mortgage: In September 1990, X Finance lent ¥3 billion to A Industries. As security for this substantial loan, B Construction (acting as a third-party surety) granted a mortgage to X Finance over a building it owned ("the Building"). This mortgage was duly registered.

- Debtor's Default: A Industries subsequently defaulted on the loan in March 1991 and was declared bankrupt in December 1992.

- Leasing of the Mortgaged Building: B Construction, the owner of the Building, had been leasing it out. Initially, it generated a total monthly rent of over ¥7.07 million from multiple tenants. In January 1993, B Construction entered into a new master lease agreement for the entire Building with Y Corp.. Under this master lease, Y Corp. would pay a monthly rent of ¥2 million, provided a ¥100 million security deposit, and was granted the freedom to assign its lease or sublet the premises (with the original tenants presumably becoming sub-lessees of Y Corp.). This master lease was also registered.

- Assignment of Rent Claims: On April 19, 1993, C Corp. lent ¥70 million to B Construction. The very next day, April 20, 1993, B Construction, as a form of substitute performance (daibutsu bensai) for this loan from C Corp., assigned its future rent claims against Y Corp. (for the period from May 1993 to April 1996 – three years' worth of rent) to C Corp.. Y Corp. (the lessee) formally consented to this assignment by executing a document with a certified date (kakutei hizuke), which is a method in Japan for perfecting a claim assignment against the debtor and third parties.

- Mortgagee's Attempt at Subrogation: On May 10, 1993, X Finance, the mortgagee, initiated steps to exercise its right of subrogation over the rental income from the Building. It obtained a court order attaching B Construction's rent claims against Y Corp., up to the outstanding amount of its loan to A Industries (which was over ¥3.8 billion at this point). This attachment order was formally served on Y Corp. (the lessee and thus the debtor of the rent claims) on June 10, 1993.

- The Lawsuit: X Finance later adjusted its attachment (withdrawing it for rents due from April 1994 onwards after securing an attachment on Y Corp.'s sub-rental income) and sued Y Corp. directly for the collection of rents due from July 1993 to March 1994, amounting to ¥18 million (based on the ¥2 million monthly rent payable by Y Corp.). Y Corp. defended this by asserting that the rent had already been validly assigned to C Corp. and that this assignment, being perfected before X Finance's attachment, took priority.

The Lower Courts' Position: Assignment Wins if Perfected First

The District Court initially found for X Finance, not on the basis of priority, but by holding that B Construction's assignment of rents to C Corp. constituted an abuse of rights intended to obstruct X Finance's collection efforts. However, the High Court reversed this. It held that C Corp.'s assignment of the rent claim, having been perfected by Y Corp.'s consent with a certified date before X Finance's attachment order for subrogation was served, took priority. The High Court rejected X Finance's abuse of rights argument. X Finance appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other things, that the priority between a mortgagee's right of subrogation over rent and an assignment of that rent should be determined by the date of the mortgage registration, not by the timing of the subrogation attachment versus the perfection of the assignment.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision (January 30, 1998): Mortgagee Subrogation Prevails

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's core finding on priority and ruled largely in favor of X Finance, establishing a significant precedent.

- Purpose of the "Attachment" Requirement for Subrogation (Civil Code Article 304(1) proviso): The Court began by interpreting the purpose of the proviso in Article 304, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code (which is applied to mortgages via Article 372). This proviso states that a creditor exercising subrogation must "attach" the target claim (e.g., rent) "before its payment or delivery." The Supreme Court reasoned that this requirement is primarily intended to protect the third-party obligor (the lessee, Y Corp., in this case). Because the mortgage's effect extends to the rent claim (the object of subrogation), the lessee paying rent directly to the mortgagor-lessor could be placed in an unstable legal position, potentially facing a second demand from the mortgagee. The attachment by the mortgagee clarifies the situation: before the attachment order is served on the lessee, the lessee can safely pay the lessor (or an assignee like C Corp. if the assignment is valid against the lessor); after service, the lessee should pay the attaching mortgagee (or deposit the funds if there are conflicting claims) to avoid the risk of double payment.

- "Payment or Delivery" in Article 304(1) Does NOT Include "Assignment": This was a crucial part of the Supreme Court's reasoning. It held that the phrase "payment or delivery" in the proviso does not encompass the "assignment of the claim" itself.

- Mortgagee Can Exercise Subrogation Even After a Perfected Assignment: Consequently, the Supreme Court concluded that a mortgagee (X Finance) can exercise its right of subrogation by attaching the rent claim even after that rent claim has been assigned by the mortgagor-lessor (B Construction) to a third party (C Corp.) and that assignment has been perfected against third parties (e.g., through consent with a certified date from the lessee Y Corp.).

- Key Reasons for Prioritizing the Mortgagee's Subrogation in this Context: The Court provided several grounds for this significant conclusion:

- Linguistic Interpretation: The words "payment or delivery" in Article 304(1) do not naturally or obviously include the concept of "assignment of a claim". There is no inherent legal reason why an assignment of the rent claim should automatically terminate the mortgage's effect on that claim.

- Continued Protection for the Third-Party Obligor (Lessee): Even if the mortgagee is allowed to attach the rent claim after it has been assigned, the lessee (Y Corp.) is not unduly prejudiced. If the lessee has already paid rent to the assignee (C Corp.) before being served with the mortgagee's attachment order, that payment is valid and discharges the lessee's obligation for that period, effective even against the mortgagee. For any rent not yet paid, the lessee can protect themselves by depositing the rent with a legal deposit office if there are conflicting claims.

- Publicity of the Mortgage's Effect on Rental Income: The Court controversially stated: "the fact that the effect of the mortgage extends also to the rent claim which is the object of subrogation can be considered as having been made public by the registration of the mortgage securing the principal obligation". This suggests that the mortgage registration itself serves as a form of public notice regarding the mortgagee's potential claim over future rental income.

- Preventing Easy Evasion by the Mortgagor: If a perfected assignment of rent claims always took priority over a mortgagee's subsequent attempt at subrogation, mortgagors could easily defeat the mortgagee's rights by quickly assigning away future rents before the mortgagee had a chance to react and attach them. The Court stated that "this would unfairly harm the interests of the mortgagee".

- Application to the Facts: Based on this reasoning, X Finance's subrogation, effected by attaching the rent claims, was held to take priority over C Corp.'s earlier perfected assignment of those same rent claims. The Supreme Court found that X Finance was entitled to the ¥18 million in rents it claimed. It therefore reversed the High Court's decision on this point and upheld the District Court's award to X Finance.

The Rationale Behind the "Attachment" Requirement Revisited

This judgment offered a distinct interpretation of the "attachment" requirement in Article 304(1) for mortgage subrogation, diverging from some traditional views:

- Traditional Theories:

- The "Priority Preservation Theory," often associated with older case law, viewed the attachment as a necessary step for the subrogating creditor to "preserve their priority" against other claimants. Under this view, if a third party (like an assignee) perfected their rights to the claim before the mortgagee's attachment, the subrogation would typically be defeated.

- The "Specificity Maintenance Theory," popular in academic circles, argued that a security interest inherently extends to the value substitutes of the collateral. Attachment was seen as necessary merely to keep these proceeds identifiable and prevent them from commingling with the debtor's general assets. This theory was more amenable to allowing subrogation despite prior assignments, as long as the proceeds hadn't actually been paid out.

- The 1998 Judgment's Focus: The Supreme Court in this case uniquely emphasized the "Third-Party Obligor Protection" (i.e., protecting the lessee from double payment) as the primary purpose of the attachment requirement for mortgage subrogation. It coupled this with the groundbreaking assertion that the mortgage registration itself provides public notice of the mortgagee's potential future claim on rents.

Impact and the Broader Context of Subrogation Law

This 1998 decision was widely seen as a significant strengthening of mortgagees' rights to claim rental income, particularly against strategies by mortgagors to assign away such income streams, potentially to the detriment of the mortgagee.

- Distinction from Subrogation for Statutory Preferential Rights: It's crucial to contrast this ruling with how subrogation works for other types of security interests, particularly statutory preferential rights (sakidori tokken), such as the one for the sale of movables. These preferential rights, unlike mortgages, generally lack a comprehensive public registration system. In a later case concerning a preferential right for the sale of movables (Supreme Court, February 22, 2005, Minshū Vol. 59, No. 2, p. 314, which followed on from the M78 case discussed previously), the Supreme Court held that a perfected assignment of the resale proceeds claim does defeat a subsequent attempt at subrogation by the holder of the preferential right. The explicit reason given for this different outcome was the lack of public notice for the underlying preferential right, as compared to the registered publicity of a mortgage. This established that the nature and publicity of the underlying security right are critical factors in determining the priority of subrogation against assignments.

- Complex Subsequent Rulings on Mortgage Subrogation: The broad pronouncements in the 1998 judgment, especially regarding the all-encompassing publicity effect of mortgage registration for future rent claims, have been the subject of ongoing academic discussion and have been implicitly nuanced by later Supreme Court decisions in different contexts. For example:

- In a case involving a mortgagee's subrogation over rent versus a lessee's right to set off a claim against the lessor (Supreme Court, March 13, 2001, Minshū Vol. 55, No. 2, p. 363, the "M85 case"), the Court, while still acknowledging that mortgage registration publicizes the subrogation right, held that a set-off by the lessee using a claim acquired before the mortgagee's attachment of the rent was generally permissible and could be asserted against the mortgagee.

- In a case concerning subrogation versus an assignment order obtained by a general creditor over expropriation compensation money (Supreme Court, March 12, 2002, Minshū Vol. 56, No. 3, p. 555), the Court held that the mortgagee's subrogation only prevailed if their attachment was effected before the assignment order was served on the third-party obligor (the entity owing the compensation).

These later decisions suggest that while the 1998 judgment provided strong protection for mortgagees against assignments of future rent, the precise interplay and priority rules in other scenarios involving different types of competing claims or third-party actions may involve additional considerations beyond simply the date of mortgage registration.

The Ongoing Doctrinal Debate

Legal commentators suggest that the 1998 judgment represents a significant, perhaps policy-driven, effort to protect mortgagees from attempts to dilute their security over rental income through assignments. However, its broad theoretical assertion that mortgage registration alone serves to publicize a future, potential right of subrogation over yet-to-be-accrued rent claims remains a point of sophisticated academic debate. The Civil Code was amended in 2003, with changes to Article 371 explicitly stating that a mortgage extends to fruits (including rent) arising after the debtor's default. While this 1998 judgment dealt with the law prior to that amendment, the amendment itself now provides a clearer substantive basis for a mortgagee's claim to post-default rental income, operating alongside the subrogation mechanism. The interaction between the principles of this 1998 judgment and the amended Article 371 continues to be analyzed by scholars. Some suggest that the 1998 judgment's strong stance might be best understood in its specific context of preventing strategic assignments designed to undermine mortgage security, rather than as an overarching redefinition of subrogation principles for all scenarios.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of January 30, 1998, stands as a landmark decision in Japanese mortgage law. It decisively prioritized a mortgagee's right to exercise subrogation over rental income from the mortgaged property, even against a third party who had previously taken a perfected assignment of those future rent claims from the mortgagor. The Court's reasoning, emphasizing the protective function of mortgage registration as public notice of the mortgagee's potential claim on rents and interpreting the "attachment" requirement for subrogation primarily as a measure to safeguard the lessee, marked a significant bolstering of mortgagees' security over income-producing properties. While subsequent case law has introduced further nuances in different factual contexts, this judgment remains a critical authority, highlighting the judiciary's efforts to strike a balance between protecting secured creditors and addressing the rights of other parties involved in transactions concerning the income generated by mortgaged real estate.