More Than Just Land: Japanese Supreme Court on Mortgages Covering Garden Stones and Lanterns

Date of Judgment: March 28, 1969

Case Name: Third-Party Objection to Object of Compulsory Execution

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

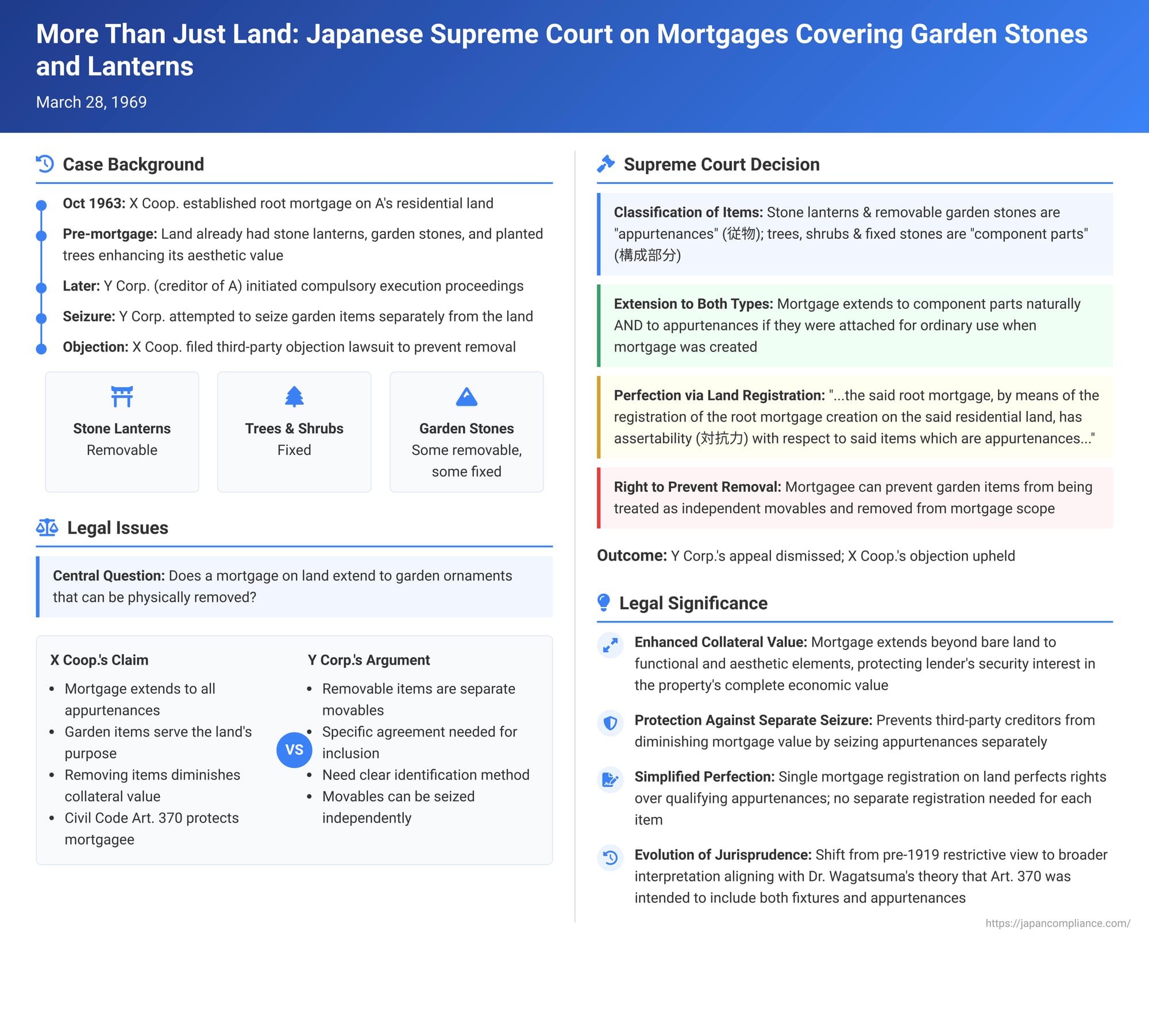

When a mortgage is placed on real property, it's generally understood to cover the land and any buildings on it. But what about items that enhance the property's use and enjoyment, like garden ornaments or landscaping features? Do these "extras" also fall under the mortgage's umbrella? Article 370 of the Japanese Civil Code states that a mortgage extends to "all things which have been added to the mortgaged immovable to form one body therewith," as well as to rights existing over the immovable, unless otherwise provided by specific agreement or law. The interpretation of this provision, particularly concerning "appurtenances" (jūbutsu), was the focus of a significant Supreme Court of Japan judgment on March 28, 1969.

The Serene Garden and the Legal Storm

The dispute centered on a residential property owned by an individual, A.

- The Mortgage: On October 8, 1963, X Coop. (a cooperative, the plaintiff/appellee) entered into an agreement with A to establish a root mortgage (neteitōken) over A's residential land. This root mortgage was intended to secure present and future debts, up to a limit of ¥1.5 million, owed by another party, B, to X Coop. under a current deposit transaction agreement between X Coop. and B. The root mortgage was formally registered on October 10, 1963.

- Pre-existing Garden Features: Importantly, before this root mortgage was created by A, the residential land had already been improved with various garden features to enhance its aesthetic appeal and provide a setting for constant appreciation. These features included stone lanterns (ishidōrō), planted trees and shrubs (ueki), and decorative garden stones (niwaishi). Some of the stone lanterns and a portion of the garden stones could be removed without undue difficulty, while the trees, shrubs, and other garden stones were more firmly fixed or difficult to separate from the land.

- Attempted Seizure by Another Creditor: Subsequently, Y Corp. (the defendant/appellant), which held an enforceable notarial deed for a monetary loan claim against A (the landowner), initiated compulsory execution proceedings. Y Corp. targeted the aforementioned stone lanterns, trees, and garden stones on A's land for seizure to satisfy its claim against A.

- X Coop.'s Objection: X Coop., as the mortgagee, filed a third-party objection lawsuit. X Coop. argued that these garden items were covered by its pre-existing root mortgage on the land, and that their separate seizure and removal by Y Corp. would diminish the overall collateral value of the mortgaged property, thereby impairing X Coop.'s security interest.

Lower Courts: Siding with the Mortgagee

The District Court and the High Court both ruled in favor of X Coop. They found that X Coop.'s root mortgage on the land indeed extended its effect to the disputed garden items. Consequently, they held that X Coop. had the right, based on its mortgage, to prevent these items from being removed from the scope of the mortgage's coverage (characterizing this as a right to prevent obstruction, bōgai haijo, of its mortgage rights). Y Corp.'s attempted execution against these items was therefore blocked. Y Corp. appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that for the root mortgage to cover such items, there needed to be a specific agreement to that effect and a clear method of identifying these items as part of the mortgage (meinin hōhō), which were absent here.

The Supreme Court's Affirmation (March 28, 1969)

The Supreme Court dismissed Y Corp.'s appeal, upholding the lower courts' decisions.

- Classification of the Garden Items: The Court began by categorizing the items in question:

- The stone lanterns and the removable garden stones were deemed "appurtenances" (jūbutsu) of the mortgaged residential land.

- The planted trees, shrubs, and the garden stones that were difficult to remove were considered "component parts" (kōsei bubun) of the land itself.

- Mortgage Extends to Both Component Parts and Appurtenances: The Supreme Court stated that the effect of the root mortgage on the residential land naturally extended to items that were its component parts. Furthermore, crucially, it also extended to the appurtenances, provided these appurtenances were attached to the land for its ordinary use at the time the root mortgage was created. The Court noted that the High Court had properly found this condition of attachment for ordinary use to be met for the stone lanterns and removable garden stones. For this extension to appurtenances, the Court cited a Great Court of Cassation precedent (March 15, 1919, Minroku Vol. 25, p. 473).

- Perfection of Mortgage Effect over Appurtenances via Land Mortgage Registration: The most significant part of the ruling concerned how the mortgage's effect on these appurtenances is asserted against third parties like Y Corp. The Supreme Court held:

"...in such a case, it is reasonable to construe that the said root mortgage, by means of the registration of the root mortgage creation on the said residential land, has assertability (taikōryoku) under Article 370 of the Civil Code with respect to the said items which are appurtenances, as well as, of course, with respect to the said items which are component parts thereof, unless there are special circumstances such as an agreement to exclude them from the effect of the mortgage."

This means that the single act of registering the mortgage on the land itself is sufficient to perfect the mortgage's claim over qualifying appurtenances against third parties. No separate registration or specific identification method for the appurtenances is required.

- X Coop.'s Right to Protect Its Collateral: Based on this, the Supreme Court concluded that X Coop., by virtue of its root mortgage, possessed the right to prevent the garden items (both component parts and appurtenances) from being treated as independent movables and thus removed from the scope of its mortgage lien. Therefore, X Coop. was entitled to demand the exclusion of these items from Y Corp.'s compulsory execution proceedings. The High Court's judgment affirming this was deemed correct.

The Legal Foundation: Civil Code Article 370 and Appurtenances (Jūbutsu)

This judgment revolves around the interpretation of two key Civil Code articles:

- Article 370 (Scope of Mortgage): "A mortgage extends to all things which have been added to the mortgaged immovable to form one body therewith (fuka ittaibutsu), unless otherwise provided for by an act of creation or by the provisions of law. However, this shall not apply if the mortgagor was entitled to separate such things from the mortgaged immovable by exercising a right over another person’s property." The term fuka ittaibutsu literally means "things added to and forming one body with."

- Article 87 (Principal Thing and Appurtenance):

- Paragraph 1: "If the owner of a thing attaches another thing owned by him/her thereto in order to permanently facilitate the use of such thing, the thing so attached is referred to as an "appurtenance" (jūbutsu)."

- Paragraph 2: "An appurtenance follows the disposition of the principal thing."

The historical debate concerned whether the term fuka ittaibutsu in Article 370 was intended to cover only "fixtures" (fugōbutsu – things physically integrated into the immovable, per Article 242) or if it also encompassed "appurtenances" (jūbutsu) which, while serving the principal thing, might retain some physical separability.

Evolution of Judicial Thinking

The Supreme Court's 1969 judgment marked an important step in a long-running jurisprudential development:

- Early View (Pre-Taishō 8): The Great Court of Cassation initially held a restrictive view, suggesting that a mortgage on land did not extend to movable appurtenances, primarily because movables themselves could not be the object of a mortgage under the general Civil Code provisions. Article 370 was seen as applying only to fixtures that lost their independent identity by becoming part of the immovable. This approach was problematic as it could prevent a mortgagee from realizing the full functional value of a property (e.g., a factory with its machinery) if appurtenances were treated separately.

- The Taishō 8 (1919) Shift: Influenced by scholars like Dr. U (Ume Kenjirō), who argued based on Article 87(2) (disposition of principal includes appurtenance), the Great Court of Cassation modified its stance. The 1919 decision held that a mortgage on real property did extend to appurtenances that were already in place at the time the mortgage was created. However, this was still viewed as an application of Article 87(2) rather than a broadening of Article 370, and it didn't explicitly cover appurtenances installed after the mortgage was created.

- Dr. W's (Wagatsuma Sakae) Influence: The highly influential scholar Dr. W conducted extensive historical research into the drafting of Article 370. He concluded that the drafters originally intended the scope of Article 370 (which used different terminology in earlier drafts, such as "increase or improvement") to include both fixtures and appurtenances. The eventual, somewhat ambiguous wording of "things added to and forming one body therewith" was, in his view, a result of imperfect reconciliation with German Civil Code concepts of principal things and appurtenances that were being incorporated into Japanese law at the time. Under Dr. W's interpretation, Article 370 itself provides the basis for a mortgage to extend to appurtenances, regardless of whether they were installed before or after the mortgage, and the mortgage registration on the principal immovable suffices for perfection.

- The 1969 Judgment's Contribution: This Supreme Court judgment is significant because, while affirming the extension of the mortgage to pre-existing appurtenances (consistent with the 1919 Taishō ruling), it explicitly cited Article 370 as the basis for the mortgage registration on the land being sufficient to assert the mortgage's effect over these appurtenances against third parties. This was a crucial clarification. As legal commentary suggests, this implies that the Court also likely views Article 370 as the primary basis for the extension of the mortgage's effect itself to appurtenances, bringing the judicial interpretation more closely in line with Dr. W's influential theory.

Implications of the Judgment

This decision has several important practical implications:

- Enhanced Collateral Value: It allows lenders (mortgagees) to more reliably consider the value of common appurtenances when assessing the overall worth of a mortgaged property. This is because the mortgage's reach is not confined strictly to the bare land or building but includes items that contribute to its functional and economic use.

- Protection Against Third-Party Creditors: General creditors of the mortgagor (like Y Corp. in this case) cannot easily seize and sell off appurtenances of a mortgaged property if those appurtenances are deemed covered by the mortgage. The mortgagee's prior registered right over the principal property effectively shields these related items.

- Perfection Made Simpler: By confirming that the mortgage registration on the principal immovable perfects the mortgage's effect over qualifying appurtenances, the judgment avoids the need for cumbersome separate registration or identification methods for each appurtenance, which would be impractical.

- Potential Extension to Post-Mortgage Appurtenances: Although this case dealt with appurtenances existing at the time the mortgage was created, the judgment's reliance on Article 370 (which doesn't inherently distinguish based on timing of attachment, according to Dr. W's theory) strongly supports the prevailing academic view that a mortgage should also cover appurtenances installed after its creation. Subsequent lower court decisions have indeed affirmed this principle.

Ongoing Discussions and Considerations

The scope of a mortgage's effect on appurtenances continues to be a subject of academic discussion, even after this landmark ruling:

- Focus on Article 370's Application: Some scholars argue that the core issue is simply whether a particular item factually meets the criteria of being "added to and forming one body with" the immovable under Article 370 on a case-by-case basis, rather than getting caught up in semantic debates about "fixtures" versus "appurtenances". However, legal commentary points out that Article 370 itself requires interpretation, and the established legal concepts of fixtures and appurtenances provide necessary criteria for determining what constitutes a relevant "addition" warranting unified treatment with the mortgaged immovable.

- Limits Based on Mortgagor's Intent or Value: Questions have been raised about whether there should be limitations, perhaps based on the mortgagor's reasonable expectations or if the appurtenances are exceptionally valuable relative to the principal property. The general view, however, is that if an item truly qualifies as an appurtenance due to its functional and economic subservience to the principal property, the mortgage should extend to it regardless of its independent value, as parties would typically expect unified treatment. Exceptionally high-value items might, in many cases, not meet the criteria for being mere appurtenances in the first place.

- Residential vs. Commercial Mortgages: Some have suggested that specific considerations might apply to residential mortgages, potentially limiting the mortgage's reach over appurtenances to protect consumer homeowners and their essential belongings. However, the counterargument is that if the dwelling itself can be sold under foreclosure, preserving only certain appurtenances offers limited practical benefit. Protection of essential household goods from seizure is typically addressed by other specific provisions in civil execution law (e.g., Civil Execution Act Article 131) rather than by altering the general scope of mortgage law.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of March 28, 1969, was a pivotal decision in Japanese mortgage law. It clarified that a mortgage on real property extends its protective reach not only to the land and its integral components but also to appurtenances—like the garden stones and lanterns in this case—that serve the ordinary use of the principal property. Crucially, the Court established that the registration of the mortgage on the land itself suffices, under Article 370 of the Civil Code, to assert this extended effect against third parties. This ruling supports a more unified approach to valuing and securing mortgaged assets, strengthens the position of mortgagees, and aligns Japanese law with a functional understanding of how properties and their appurtenances are used and valued together.