More Than Just Code: Japanese Supreme Court on "Defects" in Construction When Agreed Specifications Aren't Met

Judgment Date: October 10, 2003

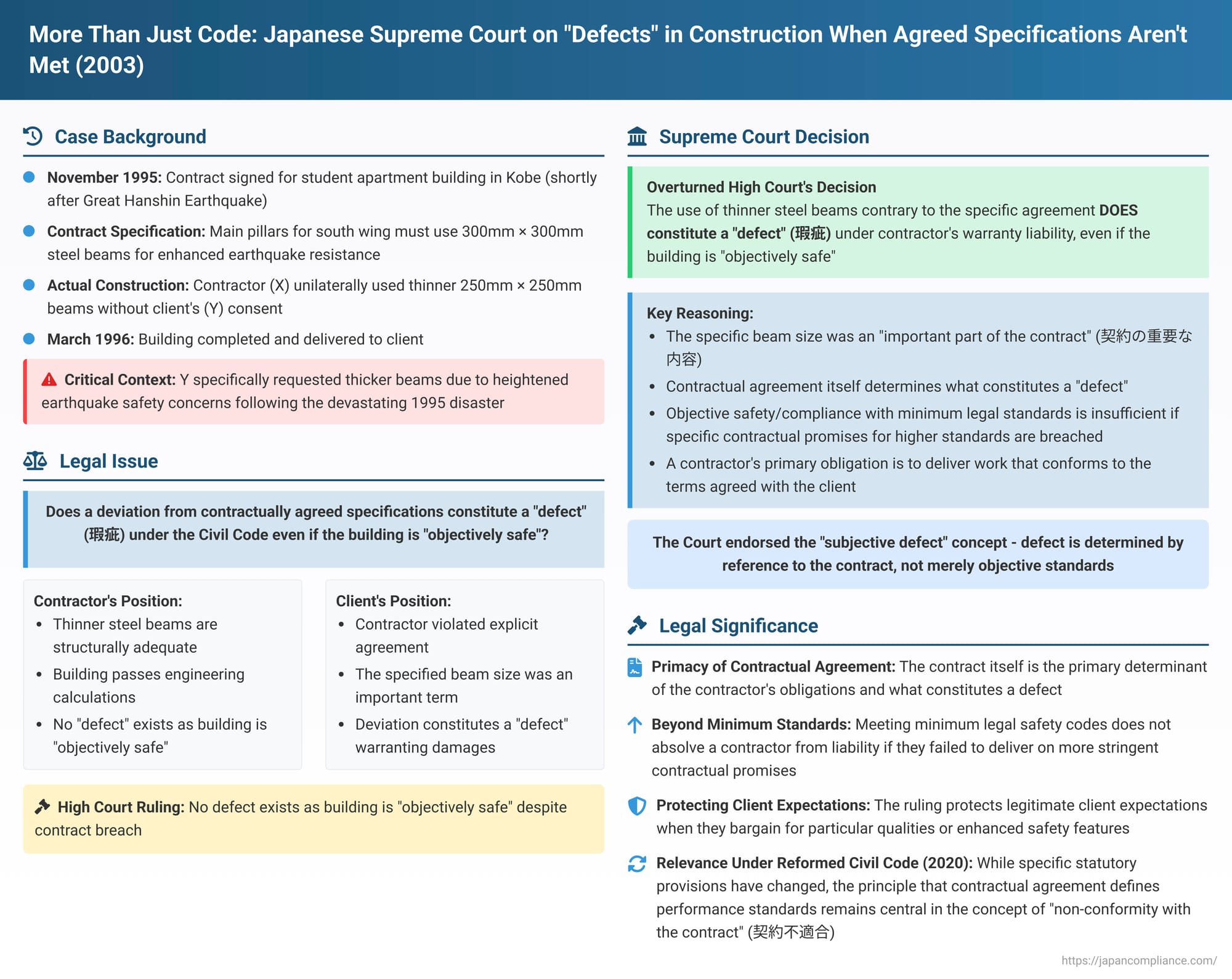

When a client commissions a building, they expect it not only to be safe and comply with legal standards but also to be built according to the agreed-upon plans and specifications. But what happens if a contractor deviates from a specific, important contractual requirement – for instance, using slightly less robust materials than promised for key structural elements – yet the resulting building is still deemed "objectively safe" according to engineering calculations and meets minimum building codes? Does such a deviation constitute a "defect" (瑕疵 - kashi) under Japan's (former) Civil Code, entitling the client to remedies? The Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, addressed this critical question in a judgment on October 10, 2003 (Heisei 15 (Ju) No. 377), clarifying that the contractual agreement itself plays a paramount role in defining what constitutes a defect.

The Construction Project: Heightened Safety Concerns Post-Earthquake

The case involved Y (the client and defendant/appellant in the Supreme Court) who, in November 1995, contracted with X (a building contractor and plaintiff/respondent) to construct a student studio apartment building ("the Building") in Kobe City. The timing of this contract was significant: it was shortly after the devastating Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake of January 1995, an event that saw many buildings collapse, leading to numerous fatalities, including university students in their lodgings. Consequently, Y was particularly concerned about the earthquake resistance and overall safety of the new building.

Reflecting these heightened concerns, during the contract negotiations, Y specifically requested a modification to the initial design for the main structural pillars of the building's south wing. To enhance seismic resistance, Y insisted, and X agreed, that these pillars should be constructed using thicker steel beams with cross-sectional dimensions of 300mm x 300mm. This specific agreement on the pillar size became, as the Supreme Court later noted, an "important part of the contract" (契約の重要な内容 - keiyaku no jūyō na naiyō).

However, during construction, X, the contractor, unilaterally decided to use thinner steel beams with dimensions of 250mm x 250mm for these main pillars. X did so without obtaining Y's consent, apparently reasoning that these thinner beams were still structurally safe according to engineering calculations and would meet regulatory requirements. The building was largely completed by early March 1996 and handed over to Y on March 26, 1996.

The Dispute: Was a Contract Breach a "Defect" if the Building Was Objectively Safe?

When X sued Y for the remaining balance of the contract price, Y counter-argued. Y claimed that the work was defective, citing, among other issues, the use of undersized steel for the main pillars in the south wing. Y asserted a right to damages for these defects, seeking to offset this amount against X's claim for the unpaid contract price.

The Osaka High Court (the lower appellate court) acknowledged that X had indeed breached the contract by using 250mm x 250mm steel beams instead of the agreed-upon 300mm x 300mm ones. However, it concluded that since structural calculations indicated the building was still safe for residential use with the thinner beams, there was no "defect" (kashi) in the construction work concerning these pillars that would give rise to warranty liability. The High Court did award Y some damages for other, unrelated minor defects but largely upheld X's claim for the remaining payment. Y appealed to the Supreme Court, challenging the High Court's finding that the use of thinner-than-agreed steel beams for crucial structural members did not constitute a legally recognized "defect."

The Supreme Court's Landmark Interpretation: Contractual Agreement Defines the "Defect"

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision on this critical point and remanded the case for recalculation of damages, affirming that X's deviation from the agreed-upon specifications did constitute a defect.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Importance of the Specific Agreement: The Court highlighted the factual context: Y's explicit concern for enhanced seismic safety following a major earthquake, leading to the specific agreement with X to use more robust 300mm x 300mm steel beams for the main pillars. This agreement wasn't a minor detail; it was a deliberate and crucial modification to the original design, aimed at achieving a higher level of safety, and had become an "important part of the contract."

- "Defect" as Non-Conformity with Important Contractual Terms: The Court ruled that because X had violated this specific and important contractual agreement regarding the pillar dimensions, the construction work on the south wing's main pillars indeed suffered from a "defect" (瑕疵がある - kashi ga aru) within the meaning of the contractor's warranty liability (瑕疵担保責任 - kashi tanpo sekinin) under the former Civil Code.

- Objective Safety vs. Contractual Obligation: The Supreme Court decisively rejected the High Court's view that objective safety or compliance with minimum legal standards was sufficient to negate a defect if specific contractual promises for higher standards were breached. The Court emphasized that a contractor's primary obligation is to deliver work that conforms to the terms of the contract agreed upon with the client. If the parties specifically bargain for and agree upon a particular quality, material, or dimension (especially for an important element like structural support intended to provide enhanced safety), then failing to meet that agreed standard is a defect, even if the resulting work happens to pass minimum legal safety codes or be deemed "structurally sound" by some objective calculation using the lesser materials.

This ruling effectively endorsed what legal commentators refer to as a "subjective defect" concept. A defect is not merely an objective flaw or a failure to meet external standards; it is, more fundamentally, a failure of the work to conform to the specific qualities and characteristics promised and agreed upon in the contract between the particular parties, especially concerning important aspects of the work.

The Supreme Court also briefly addressed a procedural point regarding the set-off of damages against the contractor's claim for the remaining payment. It confirmed (following a 1997 precedent) that when a client declares an offset of their damage claim against the contractor's claim, the client becomes liable for default interest on any post-set-off remaining balance owed to the contractor from the day after the declaration of set-off is made.

Analyzing the "Subjective Defect" Concept and Its Significance

The Supreme Court's 2003 decision was a significant clarification in Japanese construction contract law:

- Primacy of Contractual Agreement: It underscored that the contract itself is the primary determinant of the contractor's obligations and what constitutes a defect. If a higher standard or specific feature is explicitly agreed upon as an important term, that becomes the benchmark.

- Beyond Minimum Standards: Simply meeting minimum legal safety standards (like those in the Building Standards Act - 建築基準法) does not absolve a contractor of liability if they have failed to deliver on more stringent or specific contractual promises that were important to the client.

- Protecting Client Expectations: The ruling protects the legitimate expectations of clients who bargain for particular qualities or safety features, especially when those features are central to their reasons for entering the contract (as Y's desire for enhanced seismic safety was here).

- Distinction from Mere "Breach of Contract": While the High Court saw the use of thinner steel as a breach of contract, it hesitated to call it a "defect" because the building was still deemed safe. The Supreme Court clarified that such a breach of an important agreed specification is precisely what can constitute a defect for the purposes of warranty liability, entitling the client to remedies such as damages for repair, replacement, or diminution in value.

- "Important Part of the Contract": The ruling implicitly suggests that not every minor deviation from plans would constitute a remediable defect. The deviation must relate to an "important part of the contract," or a "respected agreement" between the parties. In this case, the size of main structural pillars directly linked to earthquake resistance, a specifically highlighted concern of the client, clearly met this threshold of importance.

Relevance Under Japan's Reformed Civil Code (Effective April 2020)

This Supreme Court judgment was rendered under the provisions of Japan's former Civil Code. In 2017, Japan enacted a major reform of its Civil Code concerning contract law, with the new provisions taking effect in April 2020. These reforms substantially changed the legal framework for liability for defective goods and services, including construction work:

- Abolition of "Kashi Tanpo Sekinin": The old, specialized system of "defect warranty liability" (瑕疵担保責任 - kashi tanpo sekinin), including the specific term "kashi" (defect) and articles like 634 and 635, was abolished.

- Introduction of "Non-Conformity with the Contract" (契約不適合 - keiyaku futekigō): The new Civil Code now uses a unified concept of "non-conformity with the contract" to govern a seller's or contractor's liability if the delivered goods or completed work do not match what was agreed.

- Contractual Terms as the Benchmark: The new Article 562 (mutatis mutandis applied to contracts for work via Article 559) explicitly states that if the subject matter delivered does not conform to the "kind, quality, or quantity ... as provided in the contract," the buyer/client has rights to demand repair, replacement, price reduction, or damages, and may also cancel the contract under general cancellation rules (Arts. 541, 542).

- Statutory Codification of the "Subjective" Approach: The reformed Civil Code, by making "conformity with the contract" the central criterion, essentially codifies and reinforces the "subjective defect" approach championed by this 2003 Supreme Court ruling. The primary focus is now explicitly on whether the work delivered matches the agreed terms of the specific contract between the parties.

- Elimination of Article 635 Proviso: The controversial proviso in former Article 635, which prohibited contract cancellation for defects in completed buildings, has been removed. Under the new law, cancellation is a potential remedy for non-conforming construction work, subject to the general rules for contract cancellation (e.g., material breach, opportunity to cure).

While the specific statutory provisions interpreted by the 2003 Supreme Court have been superseded, the underlying principle of the judgment—that the terms specifically agreed between the parties are paramount in defining the contractor's obligations and determining whether their work is "defective" or "non-conforming"—remains highly relevant and is, in fact, more explicitly embedded in Japan's current Civil Code. This case was an important judicial step towards recognizing the centrality of the contractual agreement in defining performance standards.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's October 2003 decision in the defective pillar case was a crucial affirmation that a contractor's failure to adhere to important, specifically agreed-upon specifications constitutes a legal "defect," even if the resulting work meets minimum objective safety standards. By prioritizing the contractual agreement, the Court underscored that clients are entitled to receive what they bargained for, especially when those bargained-for elements relate to critical aspects like enhanced safety. Although the Japanese Civil Code has since been reformed, this ruling's emphasis on the agreed terms of the contract as the benchmark for performance remains a cornerstone of Japanese contract law, now more clearly reflected in the concept of "non-conformity with the contract."