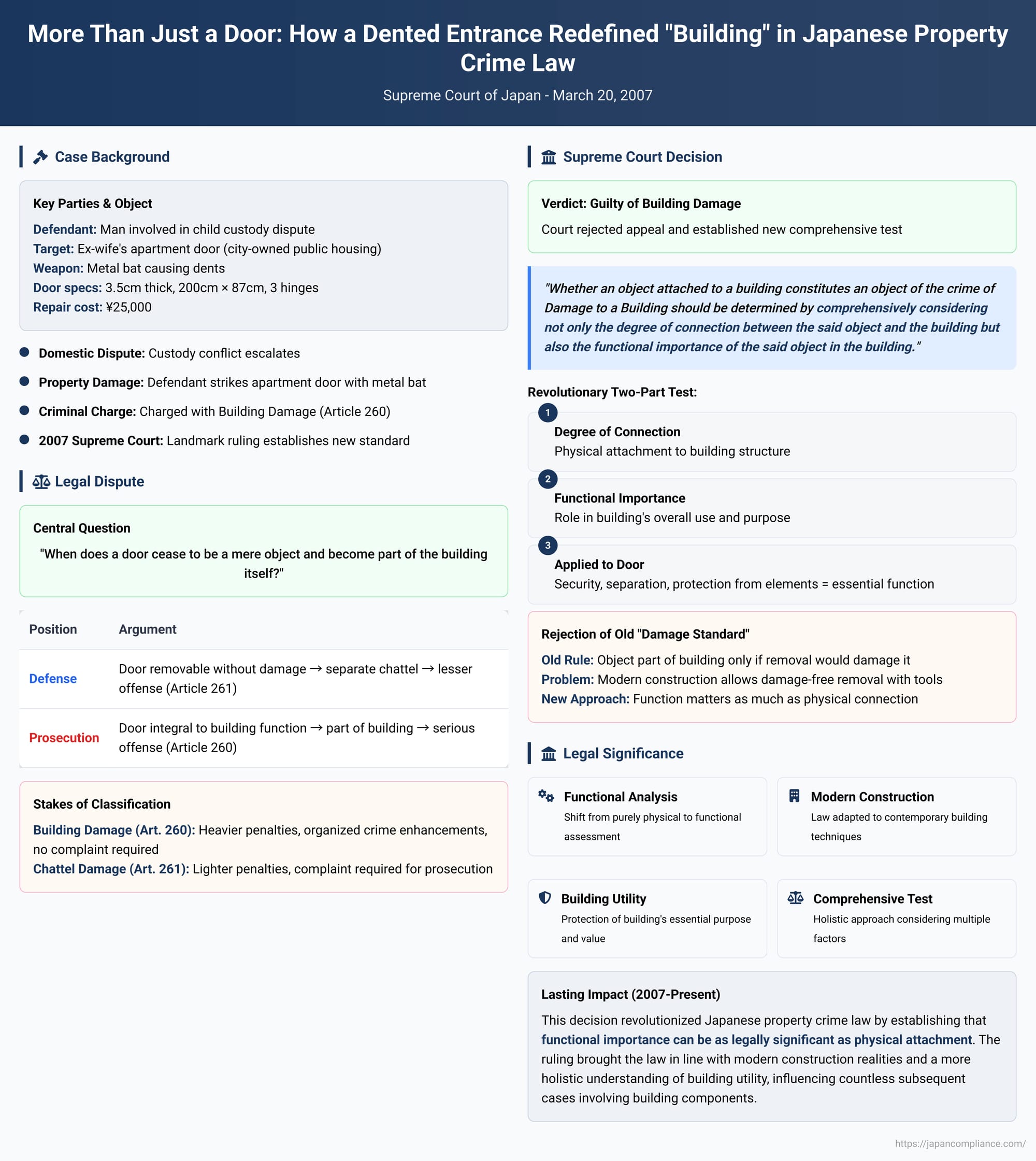

More Than Just a Door: How a Dented Entrance Redefined "Building" in Japanese Property Crime Law

In criminal law, distinctions matter. The legal line between damaging a simple object, like a piece of furniture, and damaging a building can have profound consequences. In Japan, these two offenses are governed by separate articles of the Penal Code, with Damage to a Building (Article 260) carrying significantly heavier penalties, including the possibility of enhancements for organized crime activity or for causing injury or death. Unlike the lesser offense of Damage to a Chattel (Article 261), it is also a crime that can be prosecuted without a formal complaint from the victim. This raises a critical question that blurs the line between architecture and law: when does a component, like a door, a window, or a fixture, cease to be a mere object and become an integral part of the building itself?

For nearly a century, Japanese courts relied on a simple, physical test to answer this question. But on March 20, 2007, the Supreme Court of Japan issued a landmark decision in a case involving a dented apartment door that swept away the old rule and established a new, more nuanced standard based on function as much as form.

The Facts: A Bat, a Door, and a Family Dispute

The case arose from a heated domestic situation. The defendant was involved in a child custody dispute with his ex-wife. Frustrated by their interactions, he went to her apartment, located in a city-owned public housing complex in Shimonoseki, and struck the metal front door with a metal bat. The act did not destroy the door but left it dented. The facts presented in court were specific:

- The door was a standard metal hinged door, approximately 3.5 cm thick, 200 cm high, and 87 cm wide.

- It was attached by three hinges to a frame that was itself fixed to the building.

- Structurally, the door and its frame were connected to the exterior wall, presenting an integrated appearance.

- The estimated cost to repair the dents and repaint the door was 25,000 yen.

The defendant was charged with the serious crime of Damage to a Building. His defense was a direct challenge to the definition of the object he had damaged. He argued that because the door could be easily removed from its frame with the proper tools without causing further destruction, it was not legally part of the building. Instead, he claimed, it was a separate chattel (kibutsu). If he was right, he could only be guilty of the much lesser offense of Damage to a Chattel. The lower courts convicted him of the more serious crime, and he appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Old Rule: The "Damage Standard"

The defendant's argument was based on a legal test that had been the standard in Japan since the era of the Great Court of Cassation, the nation's pre-war highest court. This traditional test, often called the "damage standard" (kison kijun), was elegantly simple:

- An object was considered part of a building if its removal would necessarily cause damage or destruction to the object itself.

- Conversely, if an object could be removed without being damaged, it remained a separate chattel.

Under this rule, items like ceiling boards or permanently installed thresholds were part of the building, while things designed for easy removal, like traditional glass shoji screens, storm shutters, or board doors, were classified as chattels. However, this standard was showing its age. Legal commentators and lower courts had noted that advances in modern construction techniques were making the test obsolete. In many contemporary buildings, essential components are designed to be replaceable and can be removed without damage using specialized tools, blurring the line that the "damage standard" tried to draw.

The Supreme Court's New Test: Connection and Function

The Supreme Court rejected the defendant's appeal and used the opportunity to formally set a new standard. The Court declared that the old "damage standard" was no longer sufficient. It established a new two-part comprehensive test:

Whether an object attached to a building constitutes an object of the crime of Damage to a Building should be determined by comprehensively considering not only the degree of connection between the said object and the building but also the functional importance of the said object in the building.

The court broke down its analysis into these two factors:

- Degree of Connection: This involves the physical attachment of the object to the building.

- Functional Importance: This assesses the role the object plays in the building's overall use and purpose.

Applying this new test to the facts, the Court found that the front door was unquestionably part of the building. It was physically connected to the exterior wall and, more importantly, it served crucial functions for the dwelling. It provided security, separated the residence from the outside world, and offered protection from wind, noise, and other elements.

In a decisive break from the past, the Court explicitly stated that the conclusion was not changed by the fact that the door could be removed without damage using proper tools. The functional role had become just as important as the physical connection.

Analysis: A Shift from Physicality to Functionality

This decision marked a significant evolution in Japanese criminal law, shifting the focus from a purely physical analysis to a functional one. The underlying rationale is tied to the very purpose of the law against damaging buildings. The crime is considered serious because the harm is not just to the damaged component but to the utility of the building as a whole. An object is legally part of a building if its damage impairs that building's essential purpose.

This functional approach could have far-reaching implications:

- Expansion of the Crime: An object with a weak physical connection but immense functional importance could now be considered part of a building. A critical, easily-removable server rack in a data center or a specialized lock on a vault could qualify.

- Limitation of the Crime: Conversely, an object that is permanently and securely affixed but has no real functional importance (e.g., a purely decorative, trivial ornament) might be excluded from the building's definition, even if damaging it requires great effort.

The 2007 ruling brings the law in line with the reality of modern construction and a more holistic understanding of what gives a building value and utility.

A Lingering Question: Was the Building's "Utility" Truly Impaired?

While the Supreme Court settled the question of whether the door was part of the building, the case leaves another critical question unanswered. Even if the door is part of the building, did the defendant's act actually cause enough harm to constitute the completed crime?

Legal commentators have pointed out that one must distinguish between the object of the crime (the building) and the harm of the crime (the impairment of the building's utility). They are not the same thing. The damage in this case was a dent; the door was not broken through, and its core functions of locking and providing a barrier were not destroyed. The repair cost was relatively minor.

This raises a difficult question: Did a small dent truly "damage the utility" of the entire dwelling? If the harm was too minor to be considered a "completed" crime, the defendant could not be convicted of it, as Japanese law does not punish an "attempt" to commit this offense. This creates a potential legal gap: if the damage is minor, a defendant may escape liability for the major offense, but because the object is now legally defined as part of the building, they also cannot be convicted of the lesser offense of damaging a chattel. Some scholars suggest that such cases highlight the need for legislative reform, such as adding fines as a sentencing option for minor damage to buildings, to ensure proportionality.

Conclusion

The 2007 decision on the dented door is a pivotal moment in the history of Japanese property crime law. It replaced a rigid, century-old physical test with a flexible, two-part standard that considers both physical connection and functional importance. In doing so, the Court aligned the law with a modern understanding of buildings as complex, functional systems. While it resolved one major legal question, it also opened the door to new and subtle debates about what level of harm is required to impair a building's utility, a conversation that will continue to shape Japanese law for years to come.