More Than an Eyesore: How Graffiti on a Public Toilet Redefined Property Crime in Japan

Is graffiti art or vandalism? While this debate rages in cultural circles, the legal world faces a more pragmatic question: is it a crime, and if so, how serious is it? Can an act that only affects a building's surface, without breaking its windows or cracking its walls, be considered a serious offense equivalent to taking a sledgehammer to the structure? In Japan, the distinction between minor mischief and a major felony can hinge on the answer.

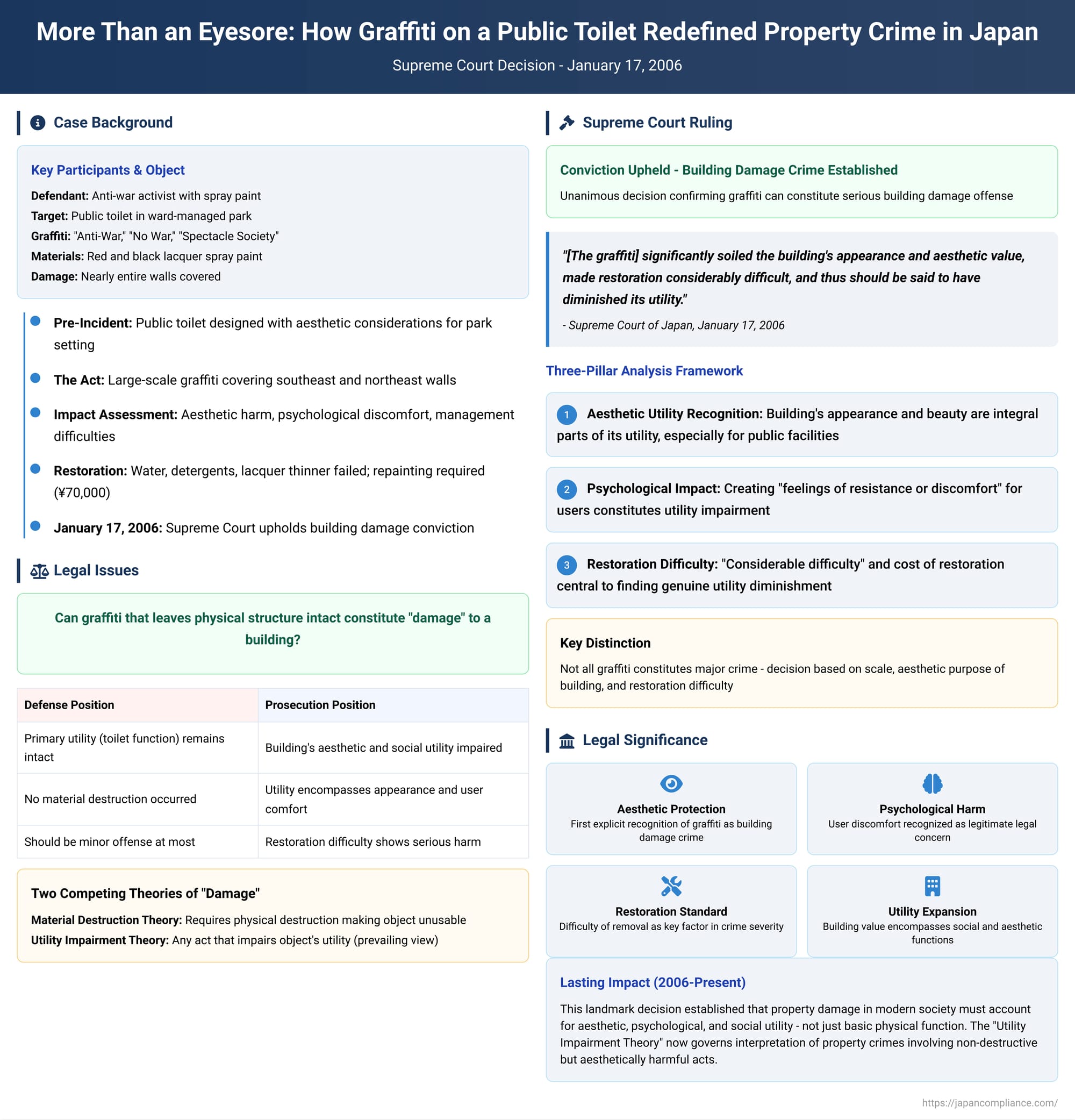

A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on January 17, 2006, provided a definitive and powerful answer. In a case involving large, spray-painted slogans on a public toilet, the nation's highest court established that graffiti can, in fact, constitute the serious crime of Damage to a Building, expanding the legal understanding of what it means to "damage" property.

The Facts: "Anti-War" on a Public Toilet Wall

The case centered on a public restroom located in a ward-managed park. The building was not a simple, utilitarian structure; its design had been given considerable thought to ensure its appearance and aesthetic value were appropriate for a public park.

The defendant, using two cans of red and black lacquer spray paint, covered the building's white exterior walls with large, bold slogans, including "Anti-War," "No War," and "Spectacle Society." The graffiti was extensive, blanketing almost the entire surface of the building's southeast and northeast walls, save for a few small areas that already had other graffiti.

The impact of this act was multifaceted:

- Aesthetic Harm: The court found that due to the size, shape, and color of the text, the building's appearance became unsightly and strange, and its aesthetic value was significantly harmed.

- Psychological Impact: The altered appearance was deemed capable of creating feelings of resistance or discomfort for potential users.

- Managerial Difficulty: From the perspective of the park's administrator, it was judged difficult to continue making the building available for public use in its defaced state.

- Difficulty of Restoration: The graffiti proved to be highly resistant to cleaning. It could not be removed with water or liquid detergents. Even lacquer thinner failed to remove it completely. The only way to fully restore the building's appearance was to repaint the walls, a process estimated to cost approximately 70,000 yen.

The defendant was charged and convicted of Damage to a Building in the lower courts, and the case was appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Question: What Does "Damage" Mean?

The core of the legal dispute was the definition of "damage" (sonkai) under Article 260 of the Penal Code. The defense argued that the defendant's actions did not impair the primary utility of the building—its function as a toilet—and therefore did not constitute "damage" in the criminal sense. This argument forced the court to confront a long-standing theoretical debate in Japanese criminal law.

There are two main theories regarding the definition of "damage":

- The Material Destruction Theory (busshitsuteki sonkai setsu): This is a narrower view, holding that "damage" requires the material, physical destruction of an object's substance, which in turn renders it unusable.

- The Utility Impairment Theory (kōyō shingai setsu): This is the broader and prevailing view in both case law and academic scholarship. It defines "damage" as any act that impairs the utility of an object.

While both theories agree that physical destruction constitutes damage, they diverge in cases like this one, where the physical structure of the building was left intact. Japanese courts have historically favored the broader Utility Impairment Theory.

The Supreme Court's Analysis: Expanding the Idea of "Utility"

The Supreme Court unanimously upheld the conviction, solidifying the Utility Impairment Theory and providing a detailed framework for its application. The Court's reasoning was that the defendant's graffiti "significantly soiled the building's appearance and aesthetic value, made restoration considerably difficult, and thus should be said to have diminished its utility."

This decision was significant for several reasons:

1. "Utility" Includes Aesthetics and Appearance

The Court explicitly rejected the defense's narrow definition of the toilet's utility. It affirmed that a building's purpose is not limited to its most basic physical function. In this case, because the building was a public facility designed with aesthetics in mind, its "appearance and beauty" were considered an integral part of its utility. This approach aligns with some academic views that a building's beauty is a utility worth protecting, especially when its harm reduces the building's use-value to a degree that it is no longer suitable for its original purpose.

2. Psychological and Emotional Impact is a Factor

The Court's consideration of the "feelings of resistance or discomfort" experienced by users is crucial. This connects the ruling to a long-standing principle in Japanese property crime jurisprudence. An early, famous precedent held that urinating into a sake flask and pot constituted property damage, not because the objects were physically broken, but because they were rendered unusable from an emotional or psychological standpoint. The 2006 graffiti decision followed this logic, confirming that making a building psychologically difficult or unpleasant to use can be a form of utility impairment. While some critics argue this could open the door to punishing intangible acts, like spreading a rumor that a toilet is haunted, case law to date has limited this principle to tangible acts like graffiti, posting bills, or physical contamination.

3. Difficulty of Restoration is a Key Metric

The Court placed significant weight on the fact that the graffiti was not easily removable. The "considerable difficulty" and cost of restoration were central to its finding that the building's utility was truly diminished. This implicitly distinguishes serious criminal damage from minor defacement that can be easily cleaned. The commentary suggests this factor is particularly important for distinguishing the felony of Damage to a Building from a violation of the Minor Offenses Act. While a very old precedent stated that the ease of restoration does not affect the establishment of the crime, later cases, including this one, show that it is a critical factor in practice, especially in cases without physical destruction.

Conclusion: A Modern Definition of Harm

The 2006 Supreme Court decision was the first to explicitly recognize graffiti as an act capable of constituting the serious crime of Damage to a Building. In doing so, it did not create a new legal theory but rather applied the existing "Utility Impairment" doctrine to a modern problem, confirming its breadth and flexibility.

The ruling established that, in the eyes of the law, a building's value and utility are not confined to its structural integrity. They also encompass its aesthetic role, its appearance, and the public's ability to use it without psychological discomfort. The Court did not declare all graffiti to be a major crime; its decision was a careful, holistic judgment based on the immense scale of the graffiti, the significant harm to the building's specific aesthetic purpose, and the considerable difficulty of restoring it to its original state. The decision sends a clear message: damaging the social, aesthetic, and psychological utility of a building can be just as serious as damaging its physical form.