Monju Reactor Challenge: Supreme Court Upholds Direct Nullity Lawsuits Despite Civil Injunction Option

Judgment Date: September 22, 1992

Case Number: Heisei 1 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 131 – Claim for Confirmation of Nullity of Reactor Installation Permit, etc.

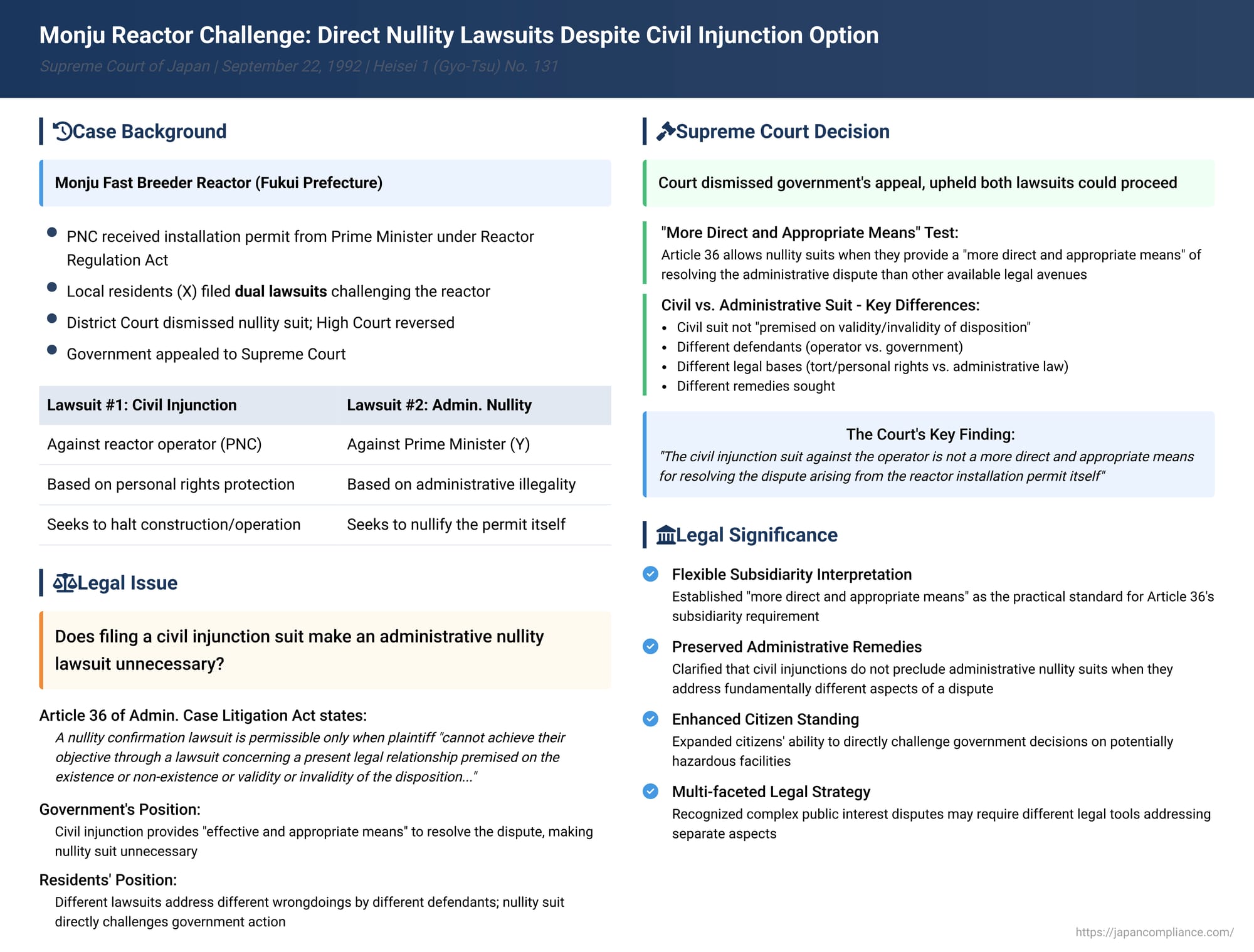

The construction of the Monju fast breeder nuclear reactor in Tsuruga City, Fukui Prefecture, was one of Japan's most controversial public projects, sparking prolonged legal battles. A significant 1992 Supreme Court decision arising from this controversy addressed a critical procedural question: when citizens file both a civil lawsuit to stop a project's operation and an administrative lawsuit to nullify the project's foundational government permit, does the existence of the civil suit render the administrative suit unnecessary or improper? The Court’s answer reinforced a pathway for citizens to directly challenge the legality of such permits.

The Monju Controversy and a Dual Lawsuit Strategy

The former Power Reactor and Nuclear Fuel Development Corporation (hereinafter "PNC" or "the Operator") planned to construct and operate the Monju fast breeder reactor. This plan received an installation permit from the Prime Minister (the Defendant/Appellee, "Y") under the Act on the Regulation of Nuclear Source Material, Nuclear Fuel Material and Reactors (hereinafter "Reactor Regulation Act").

Local residents and others opposing the reactor's construction (the Plaintiffs/Appellants, "X and other residents") launched a two-pronged legal attack:

- A civil injunction lawsuit (minji sashitome soshō) against PNC, seeking to halt the construction and operation of the Monju reactor. This suit was based on the argument that the reactor posed a threat to their lives, health, and other personal rights.

- An administrative lawsuit for nullity confirmation (mukō kakunin soshō) against Y (the Prime Minister), arguing that the reactor installation permit itself was null and void due to grave and obvious flaws in the safety assessment and licensing process.

X and other residents opted for a nullity confirmation suit because the statutory period for filing an administrative objection—which, at the time, was a prerequisite for a revocation suit concerning reactor permits under Article 70 of the Reactor Regulation Act—had already passed. A nullity suit, which asserts that an administrative act is void from its inception due to severe defects, is not subject to such strict time limits and can be a vital tool when other avenues for challenging an administrative act are closed.

Lower Courts Divided on the Nullity Suit's Propriety

The Fukui District Court, which initially handled both lawsuits (though it later separated them for judgment), dismissed the nullity confirmation suit. Its reasoning centered on Article 36 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act. This article restricts the filing of nullity confirmation suits, generally allowing them only when the plaintiff "cannot achieve their objective through a lawsuit concerning a present legal relationship premised on the existence or non-existence or validity or invalidity of the disposition or ruling in question." This is often called the "subsidiarity requirement," implying that a nullity suit is a remedy of last resort.

The District Court viewed the ongoing civil injunction suit as an "effective and appropriate means for the fundamental resolution of this dispute." It implied that through the civil injunction, X and other residents could achieve their ultimate goal of stopping the reactor, making the separate nullity confirmation suit for the permit superfluous and thus lacking the necessary legal interest under Article 36.

However, the Nagoya High Court (Kanazawa Branch), on appeal, reversed this part of the District Court's decision. The High Court found that the nullity confirmation suit did have the requisite legal interest because:

- The civil injunction suit was not legally premised on the invalidity of the reactor installation permit; its basis was the alleged infringement of personal rights by the reactor's operation.

- The civil injunction suit could not be considered a "fundamental means of resolving the dispute" that originated from the government's act of issuing the permit.

- Therefore, the nullity confirmation suit was not an indirect or roundabout means of resolution in this context.

While affirming the permissibility of the nullity suit, the High Court did limit plaintiff standing to residents living within a 20-kilometer radius of the Monju site. Both sides appealed to the Supreme Court – X and other residents on the restriction of standing, and Y (the government) on the High Court's decision to allow the nullity suit. The judgment discussed here pertains to the government's appeal.

The Supreme Court's Stance (September 22, 1992)

The Supreme Court’s Third Petty Bench dismissed the government's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's conclusion that the nullity confirmation suit was permissible despite the concurrent civil injunction suit.

Deconstructing Article 36: The "More Direct and Appropriate Means" Test

The Supreme Court's reasoning relied heavily on its established interpretation of Article 36's subsidiarity requirement. It explicitly cited and reaffirmed the principle laid out in earlier key decisions, including a 1970 case concerning agricultural land acquisition (Sup. Ct., Nov. 6, 1970, Minshū 24-12-1721) and, notably, a 1987 case concerning a land exchange disposition (Sup. Ct., Apr. 17, 1987, Minshū 41-3-286 – previously discussed).

According to this established interpretation, the condition that a plaintiff "cannot achieve their objective through a lawsuit concerning a present legal relationship premised on the... validity or invalidity of the disposition" includes not only situations where it's factually or legally impossible to get relief through such other suits (like party-public law suits or civil suits where the disposition's invalidity is a preliminary issue). Crucially, it also includes cases where the nullity confirmation suit itself is a "more direct and appropriate means of dispute resolution" (yori chokusai-teki de tekisetsu na sōshō keitai) for the conflict stemming from the administrative disposition, when compared to those other potential legal avenues.

Applying the Test: Civil Injunction vs. Nullity Confirmation in the Monju Case

The Supreme Court then applied this "more direct and appropriate means" test to the specific circumstances of the Monju litigation:

- Nature of the Civil Injunction Suit: The Court found that the civil injunction suit filed by X and other residents against PNC (the Operator), which was based on alleged infringements of personal rights due to the reactor's construction or operation, could not be considered a "lawsuit concerning a present legal relationship premised on the... validity or invalidity of the disposition" within the meaning of Article 36. The civil suit’s focus is on preventing future harm from the reactor's physical presence and operation, irrespective of the permit's formal validity. Academic commentary leading up to this decision had criticized the first instance court for treating the civil injunction suit as relevant to the subsidiarity analysis of Article 36, even though such an injunction suit is not typically a sōten soshō (a suit where the validity of an administrative act is a preliminary issue that must be decided to resolve the main private law dispute).

- Comparative Appropriateness: Furthermore, the Supreme Court held that, when compared to the nullity confirmation suit (which directly targets the legality of the Prime Minister's permit), the civil injunction suit is not a "more direct and appropriate" means for resolving the dispute arising from the reactor installation permit itself. The dispute over the permit specifically concerns the legality of the government's authorization – whether the safety reviews were adequate, whether legal procedures were followed, etc. A civil injunction against the operator doesn't resolve these questions about the underlying governmental act.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that the fact that X and other residents could, and indeed did, file a civil injunction suit against the operator did not strip their nullity confirmation suit against the government of the necessary requirements under Article 36.

Key Distinction: Different Suits, Different Aims

The crux of the Supreme Court's decision lies in recognizing the distinct functions and aims of the two lawsuits:

- The civil injunction suit primarily addresses the actions of the private (or quasi-private) operator (PNC) and seeks to prevent direct harm to the plaintiffs' personal rights. Its legal basis is tort law or personality rights, not administrative law governing the permit.

- The nullity confirmation suit directly challenges the legality of the administrative disposition (the installation permit) issued by the state. It questions the foundation of the operator's authority to build and run the reactor.

While related, these suits target different defendants and different legal wrongs. One does not necessarily obviate the need for the other, especially when the plaintiffs' goal includes a definitive judicial pronouncement on the lawfulness of the government's initial authorization. The commentary explains that the scope of review and focus are different; the civil injunction deals with personal rights infringement, while the nullity suit examines the procedural and substantive legality of the permit.

Implications of the Monju Judgment

This Supreme Court decision had several important implications:

- It firmly entrenched the "more direct and appropriate means" test as a flexible and practical standard for interpreting Article 36's subsidiarity requirement.

- It clarified that the availability of a civil injunction suit against an operator, which is not legally premised on the invalidity of an underlying administrative permit, generally does not preclude a separate nullity confirmation suit against the government concerning that permit.

- The ruling ensured that an important avenue for judicial review—the nullity confirmation suit—remains accessible for citizens seeking to challenge the fundamental legality of potentially hazardous facilities like nuclear reactors, particularly when other forms of administrative litigation (such as revocation suits) may be procedurally barred by time limits or other prerequisites.

- It implicitly acknowledges that complex public interest disputes often have multiple facets, and different legal tools may be necessary to address them comprehensively. Challenging the operator's actions and challenging the state's authorization are not mutually exclusive endeavors.

Concluding Thoughts

The 1992 Monju judgment concerning the legal interest to sue is a significant affirmation of citizens' ability to directly question the legality of governmental decisions that have profound and far-reaching consequences. By applying the "more direct and appropriate means" test, the Supreme Court ensured that procedural rules designed to prevent unnecessary litigation do not inadvertently shield potentially void administrative acts from judicial scrutiny. This decision underscores a judicial willingness to look at the practical realities of dispute resolution and the distinct roles that different types of lawsuits can play in holding both private actors and public authorities accountable.