Money Talks, But Who Does It Belong To? A Japanese Supreme Court Case on Ownership of Misappropriated Funds

Date of Judgment: January 24, 1964

Case Name: Third-Party Objection to Provisional Attachment

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

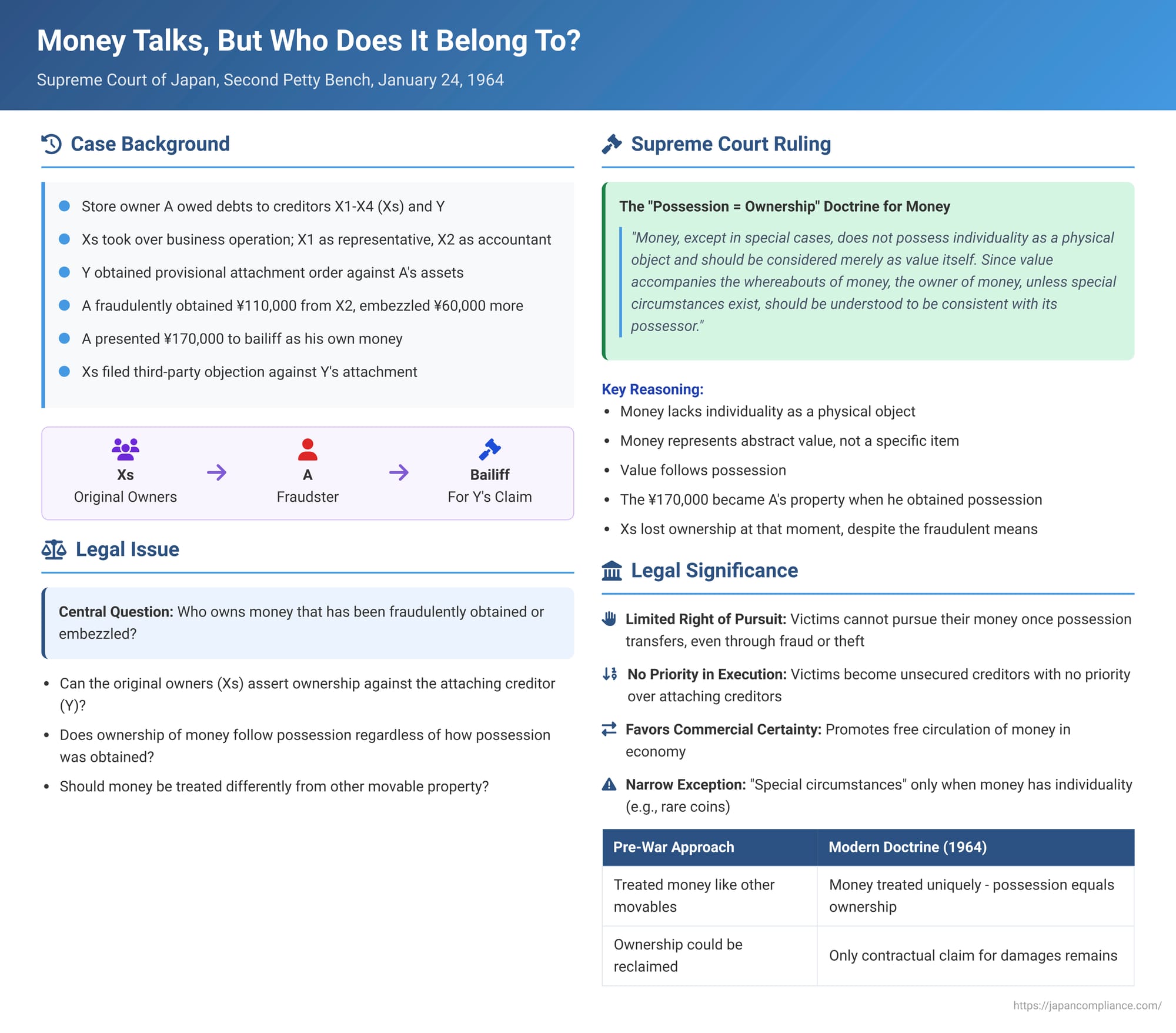

Money, in its tangible form of cash, is a peculiar asset. While it's a physical object, its primary significance lies not in its material composition but in the abstract value it represents. This unique characteristic has led to distinct legal treatment compared to other movable properties, particularly concerning the question of ownership when possession is transferred, especially through illicit means. A pivotal Japanese Supreme Court decision on January 24, 1964, addressed this very issue, solidifying a principle that has profound implications for victims of fraud and embezzlement: the doctrine that, generally, possession of money equates to its ownership.

The Facts of the Case: A Deceptive Scheme Unravels

The case arose from a series of unfortunate events involving a clothing retailer, A, and his creditors.

- The Business Arrangement: A, who operated a retail clothing store, found himself struggling to repay debts owed to a group of creditors, X1, X2, X3, and X4 (the Xs). To manage the situation, A and the Xs reached an agreement: the Xs would formally take over the entire business operation until A's debts to them were fully settled. While A was to continue with the day-to-day de facto management of the store, all sales proceeds were to be used for repaying the debts to the Xs. Under this arrangement, the Xs would provide A with 10% of the sales revenue as living expenses. X1 was designated as the representative of the creditors' group, and X2 was assigned the role of accountant.

- A's Wider Debts and an Attachment: Unknown to the Xs, A also had outstanding debts to another creditor, Y. Y successfully obtained a provisional attachment order against A's assets. Subsequently, a court bailiff arrived at A's store to execute the order.

- A's Deception and Embezzlement: Panicked that the Xs would discover the seizure, especially since the store's merchandise had already been transferred to them, A resorted to deception. He visited X2, the accountant, and, concealing the fact of the provisional attachment, falsely claimed that X1 had instructed him to collect funds for purchasing new inventory. Believing A, X2 handed over approximately ¥110,000 from the Xs' common business funds. In addition to this, A also embezzled around ¥60,000 from the store's sales proceeds.

- Presenting Funds to the Bailiff: A then took the total sum of about ¥170,000 (the defrauded ¥110,000 plus the embezzled ¥60,000) and presented it to the bailiff, falsely claiming that this money was his own, withdrawn from his personal bank account.

- The Lawsuit: Upon learning of these events, the Xs initiated a third-party objection lawsuit (a procedure under the old Code of Civil Procedure Art. 549, now governed by Art. 38 of the Civil Execution Act) against Y, the attaching creditor. The Xs asserted that the seized money rightfully belonged to them and sought to prevent Y from executing the attachment against these funds.

The Legal Journey: Lower Courts and the Supreme Court's Verdict

The dispute progressed through the Japanese court system:

- The District Court: The initial court found in favor of the Xs, recognizing their third-party objection and, by implication, their ownership of the funds.

- The High Court (Fukuoka High Court): Y appealed this decision. The High Court reversed the District Court's ruling. It held that A had acquired ownership of the money obtained through fraud from X2, as well as the embezzled sales proceeds, at the moment he gained possession of them. Consequently, the execution was deemed to be against A's own money, and the Xs' third-party objection was dismissed. The Xs then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court, on January 24, 1964, dismissed the Xs' appeal, affirming the High Court's decision. The core of the Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

"Money, except in special cases, does not possess individuality as a physical object and should be considered merely as value itself. Since value accompanies the whereabouts of money, the owner of money, unless special circumstances exist, should be understood to be consistent with its possessor. Furthermore, a person who actually controls and possesses money should be regarded as the attributor of value, i.e., the owner of the money, irrespective of the reason for its acquisition or whether they have the right to justify its possession (referencing Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, November 5, 1954, Keishu Vol. 8, No. 11, p. 1675)."

Applying this principle, the Supreme Court concluded:

"In the present case... the approximately ¥110,000 became the property of non-party A when it was delivered from appellant X2, and the approximately ¥60,000 became the property of non-party A when it was embezzled; the appellants [Xs] lost their ownership at those respective times."

The High Court's judgment, being in the same vein, was deemed correct.

The "Possession Equals Ownership" Doctrine for Money

The Supreme Court's 1964 decision is a clear articulation of the "possession equals ownership" doctrine (sen'yū = shoyūken setsu) as it applies to money in Japanese law. This doctrine treats money differently from other types of tangible property for several reasons:

- Fungibility and Lack of Individuality: Unlike a unique piece of art or a specific car, one ¥10,000 note is, for all practical purposes, identical to another. Money is valued for the quantum of purchasing power it represents, not its specific physical form.

- Role as a Medium of Exchange: Money's primary function is to facilitate transactions and circulate freely. Attaching enduring ownership rights to specific notes or coins, traceable through multiple hands, would severely impede commerce.

- Value Embodiment: Money is seen less as a "thing" and more as the embodiment of abstract economic value.

This legal approach was notably championed by Professor H S (Suekawa Hiroshi). He argued that because money is highly substitutable and inherently a consumable item meant for exchange, the traditional concept of ownership (which can exist separately from possession) is ill-suited. Instead, for money, the person who actually possesses it is its owner, regardless of how that possession was obtained. This view became influential and was adopted in post-World War II Supreme Court precedents, including a 1953 decision and the 1954 criminal case cited in the 1964 judgment. This doctrine is also the prevailing view in Japanese legal academia.

This contrasts sharply with pre-war judicial practice, which tended to treat money more like other movable goods. Under that older approach, if the underlying act causing the transfer of possession (e.g., fraud) was void, ownership might not pass, and the original owner could potentially reclaim the money unless a third party had acquired it under the rules of immediate acquisition (sokuji shutoku, Article 192 of the Civil Code). The "possession = ownership" doctrine effectively means that Article 192 does not apply to money because ownership itself is deemed to transfer with possession.

However, the doctrine is not absolute. Both the Supreme Court and Professor H S acknowledged an exception for "special circumstances" (tokudan no jijō). This typically refers to situations where money is treated not as a medium of exchange but as an object in itself, such as rare coins in a collection, which are identified and segregated, thereby retaining individuality.

Consequences and Criticisms of the Doctrine

While the "possession = ownership" doctrine promotes the smooth circulation of money, it has significant and often harsh consequences for victims of theft, fraud, or embezzlement:

- Limited Right of Pursuit (tsuikyūkō): If ownership passes with possession, the original owner (like the Xs) loses their proprietary claim to the specific money. They generally cannot pursue and reclaim that money if the wrongdoer (A) passes it to a third party (Y, or any other recipient). This would hold true even if the third party received the money in bad faith.

- It's important to note that a later Supreme Court decision (September 26, 1974) provided some recourse by allowing the victim to claim unjust enrichment from a third-party recipient who acted in bad faith or with gross negligence. This, however, is a claim based on unjust enrichment principles, not a direct assertion of ownership over the original money.

- No Priority in Execution (yūsenkō): As vividly demonstrated by the 1964 case, if the wrongdoer's creditors (like Y) attach the misappropriated money while it's in the wrongdoer's (A's) possession, the victim cannot assert a third-party objection to the seizure based on their original ownership. The money is legally considered the wrongdoer's property at the time of seizure. The victim is relegated to the status of an ordinary unsecured creditor of the wrongdoer, holding, at best, a claim for damages or unjust enrichment, which often has little practical value if the wrongdoer is insolvent.

- This issue also surfaced in a prominent Supreme Court case concerning mistaken bank transfers (April 26, 1996). The Court held that the recipient of a mistaken transfer acquires a claim for the deposited amount against the bank, and the sender merely has an unjust enrichment claim against the recipient. If the recipient's creditors attach the bank account, the sender cannot claim proprietary rights over the mistakenly transferred funds, leading to a "windfall" for the attaching creditor.

These consequences have led to considerable academic criticism of the "possession = ownership" theory's blanket application. Several scholars have proposed alternative theories to provide better protection for victims:

- Professor K S (Shinomiya Kazuo) proposed a distinction between "physical ownership" (butsu shoyūken) of the money as an object and "value ownership" (kachi shoyūken) representing the economic value. In cases of theft or fraud where possession transfers without a genuine intent by the victim to transfer the underlying value, only physical ownership would pass to the wrongdoer, while value ownership would remain with the victim. If this value could be identified or traced (even if commingled, identifiable as a share), the victim could assert a proprietary claim for the return of this value, including raising a third-party objection against the wrongdoer's creditors.

- Professor M K (Katō Masanobu) suggested that victims should have a proprietary claim for value return if the money's value is specific and the wrongdoer is insolvent (if solvent, a personal claim would suffice). For pursuing money into the hands of third parties, he proposed stricter requirements, akin to those for revoking a fraudulent act (Civil Code Art. 424), such as the third party's knowledge of the wrongdoer's insolvency.

Other scholars have explored solutions drawing from trust law principles or advocating for a security interest-like priority for the victim's unjust enrichment claim. For example, Professor H M (Dōgauchi Hiroto) argued for recognizing the principal's ownership of money received by an agent in fiduciary relationships if specificity is met. Professor A O (Ōmura Atsushi) pointed to the possibility of a trust arising for the sender in the recipient's bank account in mistaken transfer cases.

The Elusive "Special Circumstances" and the Challenge of Specificity

The "special circumstances" exception, while acknowledged by the Supreme Court, remains narrowly defined. The primary example is money that is clearly individualized and set aside, such as numismatic collections. A Supreme Court case on April 10, 1992, which recognized money possessed by one heir as co-owned by all heirs (and thus part of the inheritable estate), might be seen as another instance where the simple fact of possession by one did not solely determine ownership for all purposes, potentially falling under such "special circumstances" or a distinct legal context (inheritance).

A significant hurdle for any theory that seeks to allow proprietary claims over money once it has left the victim's direct control is the requirement of "specificity" or "identifiability" (tokuteisei). Money, by its nature, tends to commingle. Once cash obtained by fraud is mixed with the fraudster's other cash, or deposited into a bank account and mixed with other funds, how can the victim's original value be specifically identified and traced to assert a proprietary claim? This is a central challenge.

The debate is particularly acute for money in bank accounts. While some argue that a mistaken transfer, for instance, should result in the sender retaining a proprietary interest in that specific quantum of value within the recipient's account, others contend that upon deposit into a current account, the money loses its individual identity and merges into the bank's general funds, with the depositor merely holding a contractual claim against the bank for that amount. This latter view would suggest that specificity is lost, making proprietary claims difficult. However, alternative views suggest that due to the fungible nature of value, specificity can be maintained within an account for tracing purposes.

Modern Extensions: The Case of Cryptocurrency

The principles debated for physical cash are now finding new battlegrounds with the advent of digital assets. For instance, a Tokyo District Court decision on August 5, 2015, ruled that Bitcoin could not be the object of ownership in the traditional civil law sense because it lacks physical corporeality and the possibility of exclusive physical control. This has sparked extensive academic discussion on the legal nature of cryptocurrencies—whether they constitute property rights, how they are "possessed" or controlled, and whether a doctrine analogous to "possession = ownership" could or should apply to them.

Conclusion

The Japanese Supreme Court's 1964 judgment in the provisional attachment case firmly established that, for money, possession is tantamount to ownership in most circumstances. This doctrine facilitates the velocity of commerce but can leave victims of misappropriation with limited recourse, especially against the wrongdoer's other creditors. While the "special circumstances" exception offers a sliver of possibility for deviating from this rule, its narrow interpretation and the inherent difficulties in proving the specificity of commingled funds mean that the possessor is usually deemed the owner. The ongoing academic debate and the challenges posed by new forms of value like cryptocurrency indicate that the law's struggle to define and regulate the ownership of "value" in its various forms is far from over, continually balancing the needs of transactional certainty against the pursuit of fairness for those wrongfully deprived of their assets.