Film-Script Edits & Moral Rights in Japan: 2024 Osaka Case

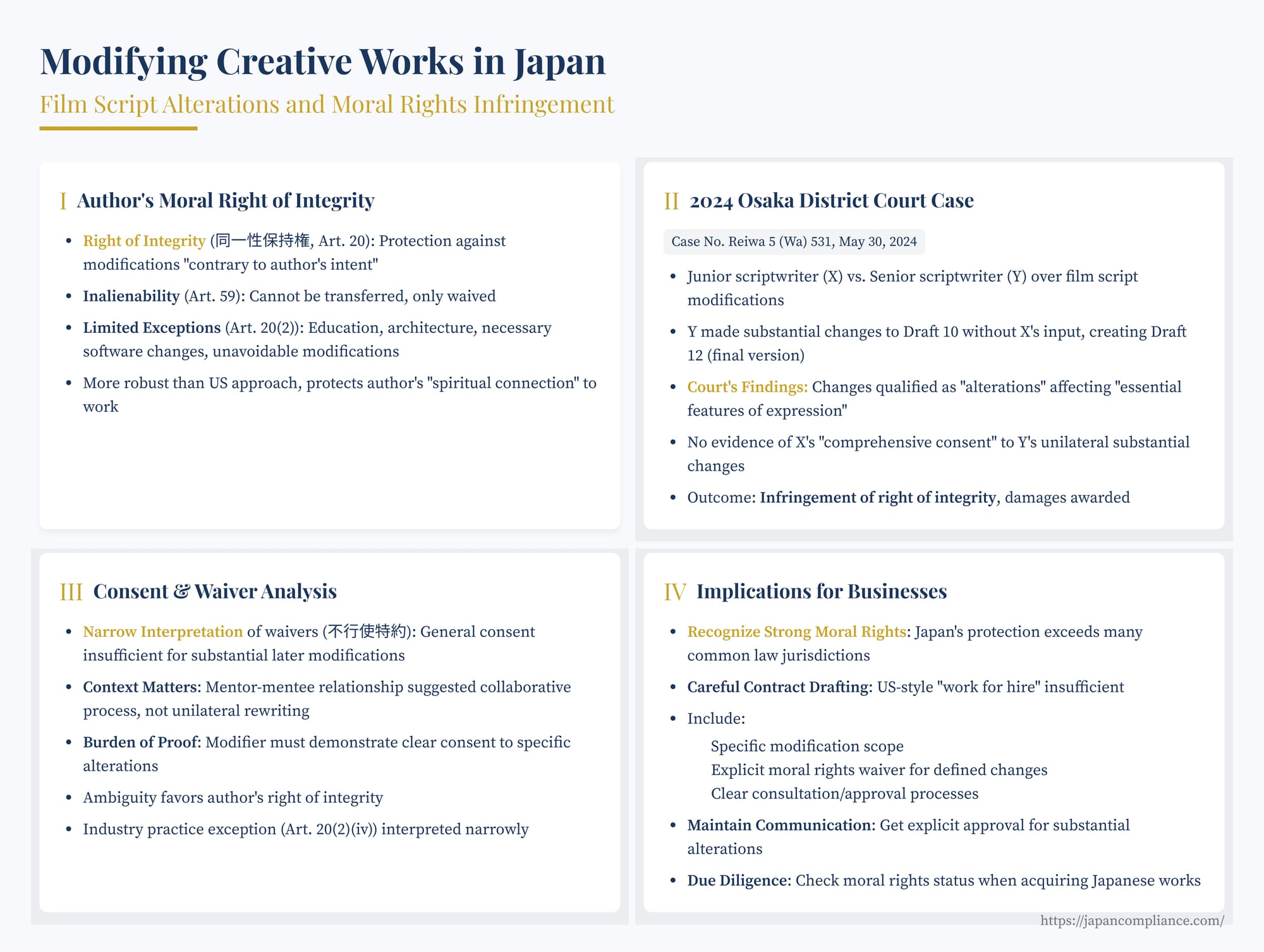

TL;DR: A 2024 Osaka court held that extensive script changes without explicit consent infringed a co-author’s moral right of integrity. The ruling shows how narrowly Japanese courts interpret waivers and how crucial clear contracts and ongoing consultation are for international film projects.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Understanding the Author’s Moral Right of Integrity in Japan

- The Case Study: Osaka District Court, May 30 2024 – Script Alterations

- Analyzing Consent and Waiver of Moral Rights

- Implications for Businesses in Creative Industries

- Conclusion

Introduction

Creative collaboration, particularly in industries like filmmaking and publishing, often involves multiple hands shaping a final work. Scripts are rewritten, manuscripts edited, designs adapted. While such modifications are frequently necessary for practical or artistic reasons, they can sometimes clash with the original creator's vision and their inherent connection to the work. In jurisdictions like Japan, which grant authors strong "moral rights," these clashes can lead to significant legal disputes.

Unlike economic rights (like reproduction or distribution) which can be freely transferred or licensed, moral rights (chosakusha jinkaku ken 著作者人格権) under Japanese copyright law protect the author's personal and spiritual relationship with their creation. One of the most crucial of these is the "right of integrity" (douitsusei hoji ken 同一性保持権), which gives authors the power to object to alterations of their work that go against their intentions. This concept often differs significantly from the intellectual property landscape familiar to US businesses, where moral rights protection is generally more limited.

A May 30, 2024, decision by the Osaka District Court (Case No. Reiwa 5 (Wa) 531) provides a compelling case study on the application of the right of integrity in the context of film script modifications involving collaborating writers. The case highlights the importance of understanding authorial consent and the potential pitfalls of altering creative works without explicit permission, even within a collaborative or mentoring relationship. This article analyzes Japan's moral right of integrity, examines the Osaka court's ruling, discusses the complexities surrounding consent and waiver, and explores the implications for businesses engaging in creative partnerships with Japanese authors.

1. Understanding the Author's Moral Right of Integrity in Japan

Japanese Copyright Act grants authors several distinct moral rights alongside their economic rights. These are personal to the author and fundamentally non-transferable.

- Moral Rights vs. Economic Rights: Economic rights concern the commercial exploitation of a work (copying, selling, adapting for profit) and can be licensed or assigned to others (e.g., publishers, studios). Moral rights protect the author's reputation and personal bond with the work. The three main moral rights are:

- Right to Make Public (Art. 18): The right to decide if, when, and how an unpublished work is released.

- Right of Attribution/Paternity (Art. 19): The right to be identified as the author and to decide how their name is displayed.

- Right of Integrity (Art. 20): The right central to the Osaka case – the right to preserve the integrity of the work and its title against alterations, cuts, or modifications (kaihen 改変) made "contrary to [the author's] intent" (sono i ni hanshite その意に反して).

- Inalienability (Art. 59): A defining feature of moral rights in Japan (and many civil law jurisdictions) is their inalienability. They belong exclusively to the author and cannot be sold, assigned, or transferred to another party, even if the economic rights are sold. They generally last for the author's lifetime (though protection against acts damaging the author's honor after death exists under Art. 60).

- Waiver and Consent (Fukoushi Tokuyaku 不行使特約): While rights themselves cannot be transferred, an author can agree not to exercise their moral rights, either generally or concerning specific modifications. This agreement (often called a fukoushi tokuyaku, or non-exercise agreement) is crucial in practice, especially in industries requiring adaptation. However, the validity and, more importantly, the scope of such consent (particularly if implied or broadly worded) are often subjects of dispute, as the Osaka case illustrates. Japanese courts tend to interpret waivers of moral rights cautiously.

- Statutory Exceptions to the Right of Integrity (Art. 20(2)): The law recognizes that some modifications are unavoidable or necessary. Article 20(2) lists specific exceptions where alterations do not infringe the right of integrity, even without the author's explicit consent. These include:

- Modifications necessary for school education purposes.

- Modifications to architectural works (expansion, remodeling, etc.).

- Necessary modifications for adapting computer programs to specific hardware or improving functionality.

- Other modifications deemed unavoidable in light of the work's nature, its purpose of use, and customary practices (shakai tsuunen 社会通念) in the relevant field. This last category is somewhat flexible but requires demonstrating the modification was essentially inevitable or standard practice.

2. The Case Study: Osaka District Court, May 30, 2024 – Script Alterations

This case involved a dispute between a junior scriptwriter (Plaintiff X) and a well-known senior scriptwriter (Defendant Y) over modifications made during the development of a film ("Film F," based on a pre-existing novel).

- Factual Background:

- X had been receiving guidance and advice from Y on scriptwriting. Y suggested X write a script based on a specific novel.

- X wrote several drafts under Y's mentorship, culminating in Draft 8.

- At a key meeting (Meeting ①) involving X, Y, the film's director (B), and the producer (A), it was agreed to proceed with making the film based on Draft 8, and certain revision principles were discussed. X and Y agreed they would share screenwriting credit.

- X subsequently produced Draft 9 based on the meeting, Y made revisions, and X, following Y's instructions, created Draft 10.

- Y then undertook substantial revisions of Draft 10, creating Draft 11, which was sent to X. X expressed surprise and dissatisfaction to Director B about numerous changes X hadn't been informed of.

- Y, B, and the producer held another meeting (X was not present). Y then created Draft 12 based on Draft 11.

- Draft 12 was designated the final shooting script (ketteikou 決定稿), and the film was produced based on it.

- X sued Y (specifically, not the production company or director), claiming the alterations made between Draft 10 (the last version X directly worked on) and Draft 12 (honken henkou 本件変更 - the disputed changes) infringed X's moral right of integrity in Draft 10. X sought monetary damages and a published apology as a measure to restore honor (under Copyright Act Art. 115).

- Key Legal Issues:

- Did Y's changes qualify as "alterations" (kaihen) sufficient to trigger the right of integrity under Article 20(1)?

- If so, were these alterations made "contrary to X's intent," or had X consented (explicitly or implicitly) to Y making such changes?

- The Court's Decision: The court found Y had infringed X's right of integrity and awarded damages, though it denied the request for a published apology.

- Finding of "Alteration": The court determined that Y's modifications were not merely superficial corrections or typo fixes. They involved substantive changes, adding Y's own interpretations and nuances regarding character motivations, dialogue, and scene descriptions. These changes affected the "essential features of the form of expression" (hyougen keishiki jou no honshitsu-teki tokuchou) in X's Draft 10 and were not trivial. (Legal commentators noted this point wasn't the main area of contention between the parties).

- Finding of "Contrary to Intent" (Lack of Consent): This was the crux of the dispute.

- Y's Defense: Y argued that at Meeting ①, X had given comprehensive consent (houkatsuteki doui) to future alterations. Y claimed that by agreeing to share credit, X implicitly accepted that Y, as the senior and renowned writer whose name was attached, would need to make necessary changes to ensure the script's quality.

- X's Position: X countered that the agreement was for collaboration, where X would continue to be involved under Y's guidance, not for unilateral rewriting by Y without X's input or approval.

- Court's Analysis: The court carefully examined the circumstances of Meeting ① and the subsequent interactions between X and Y. It found no sufficient evidence that X had given comprehensive consent for Y to make any and all alterations. Instead, the court inferred that the understanding reached was an extension of the existing mentoring relationship: X consented to Y providing advice and suggestions, which X would then incorporate. The court concluded that substantial changes significantly altering the content or expression, like those made by Y between Draft 10 and 12, required X's specific, individual consent, which was never obtained. Therefore, the alterations were deemed "contrary to X's intent."

3. Analyzing Consent and Waiver of Moral Rights

The Osaka court's decision highlights the careful scrutiny applied to claims of consent or waiver regarding moral rights in Japan.

- Narrow Interpretation of Waivers: As noted by legal commentators analyzing this case and prior precedents, Japanese courts often interpret agreements not to exercise moral rights (waivers or fukoushi tokuyaku) narrowly. General or implied consent given at the outset of a project may not be sufficient to cover substantial modifications made later, especially if those modifications go beyond what was reasonably contemplated by the author or strictly necessary for the work's intended use. Cases like the Dinosaur Illustration judgment (Tokyo High Ct., Sep 21, 1999), which required fresh consent for significant alterations beyond the initially agreed scope, exemplify this cautious approach.

- Context is Crucial: The Osaka court heavily relied on the specific context of the relationship between X and Y – that of a junior writer being mentored by a senior figure. This context supported the interpretation that X's agreement was primarily to receive guidance within a collaborative process, not to grant carte blanche for unilateral rewriting. In a different scenario, such as a clear work-for-hire agreement with explicit waiver clauses (common in the US, but needing careful drafting in Japan), the outcome regarding consent might differ.

- The Burden of Proving Consent: The case suggests the burden often falls on the party claiming consent (the modifier, producer, etc.) to demonstrate clearly that the author agreed, either explicitly or through undeniable implication, to the specific type and extent of alterations made. Ambiguity tends to favor the author's right of integrity.

- Importance of Explicit Contractual Terms: The dispute underscores the critical importance of clear contractual language. Parties involved in collaborative creation or adaptation should explicitly address:

- The scope of permissible modifications (e.g., minor edits vs. substantial rewriting).

- The process for approving changes (e.g., consultation required, author's final approval needed).

- Specific agreements regarding the non-exercise of moral rights, detailing the circumstances covered. Relying on implied consent or industry norms alone is risky.

- Industry Practice Exception (Art. 20(2)(iv)): While not the deciding factor here, the exception allowing modifications unavoidable due to "customary practices" is relevant in industries like film. Standard script development often involves revisions by directors, producers, or script doctors. However, this exception is generally interpreted narrowly and likely wouldn't cover substantial creative rewriting by a co-author contrary to the original author's expressed intent, unless such a practice was demonstrably and universally accepted as unavoidable for that specific type of collaboration.

4. Implications for Businesses in Creative Industries

The Osaka decision carries important lessons for businesses, particularly non-Japanese companies, involved in creating or adapting works with Japanese authors.

- Awareness of Strong Moral Rights: Businesses must recognize that Japan provides robust protection for authors' moral rights, exceeding that found in many common law jurisdictions like the US (outside specific areas like visual arts under VARA). The right of integrity, in particular, grants authors significant control over modifications.

- Careful Contract Drafting: Standard US-style contracts relying heavily on "work made for hire" doctrines or broad assignments of "all rights" may be insufficient to effectively manage moral rights in Japan. Contracts should include:

- Specific Clauses on Modifications: Clearly outlining the anticipated scope and nature of potential edits or adaptations.

- Explicit Moral Rights Waiver/Agreement: A carefully drafted clause where the author agrees not to exercise their moral rights (especially the right of integrity) concerning specific, defined types of modifications necessary for the project's purpose. Broad, boilerplate waivers may be challenged.

- Consultation/Approval Processes: Defining how significant changes will be discussed and approved with the original author.

- Collaborative Process Management: Beyond contracts, maintaining open communication with Japanese creators throughout the development process is crucial. Discussing proposed changes, seeking input, and obtaining explicit approval for substantial alterations can prevent disputes and preserve relationships, even if contractual waivers are in place. Ignoring the author's intent, even if believed to be contractually permitted, can lead to litigation and reputational damage.

- Due Diligence in Acquisitions: When acquiring rights to Japanese works, businesses should perform due diligence on the status of moral rights and any existing waivers or agreements related to modifications.

Conclusion

The May 2024 Osaka District Court decision regarding film script alterations serves as a potent illustration of the strength and application of the author's moral right of integrity (douitsusei hoji ken) under Japanese copyright law. The ruling confirms that substantive changes adding a collaborator's distinct interpretations can infringe this right, and significantly, that claims of authorial consent to modifications will often be interpreted narrowly by the courts. Implied or comprehensive consent given early in a collaboration may not cover later, substantial alterations made without the original author's specific agreement.

This case underscores the critical need for clarity and careful management in creative collaborations involving Japanese authors. Businesses must move beyond assumptions based on practices in jurisdictions with weaker moral rights regimes. Respecting the author's personal connection to their work, clearly defining the scope of permissible modifications contractually, and maintaining open communication throughout the creative process are essential steps to avoid infringing the powerful right of integrity and ensure successful, legally sound collaborations in Japan.

- Navigating Japan’s Evolving IP Landscape: Key Considerations for UGC, Derivative Works and Creator Rights

- Spoiler Alert: Legal Responses to Unauthorized Content Disclosure in Japan’s Manga and Anime Industry

- AI Inventorship in Japan: The DABUS Case Appeal and Its Implications for Global IP Strategy

- Agency for Cultural Affairs — Author’s Moral Rights Guide (JP)

https://www.bunka.go.jp/seisaku/chosakuken/seidokaisetsu/jinken.html