Modernizing Dispute Resolution in Japan: 2023 Reforms to Arbitration, ADR, and Civil Procedure IT

TL;DR

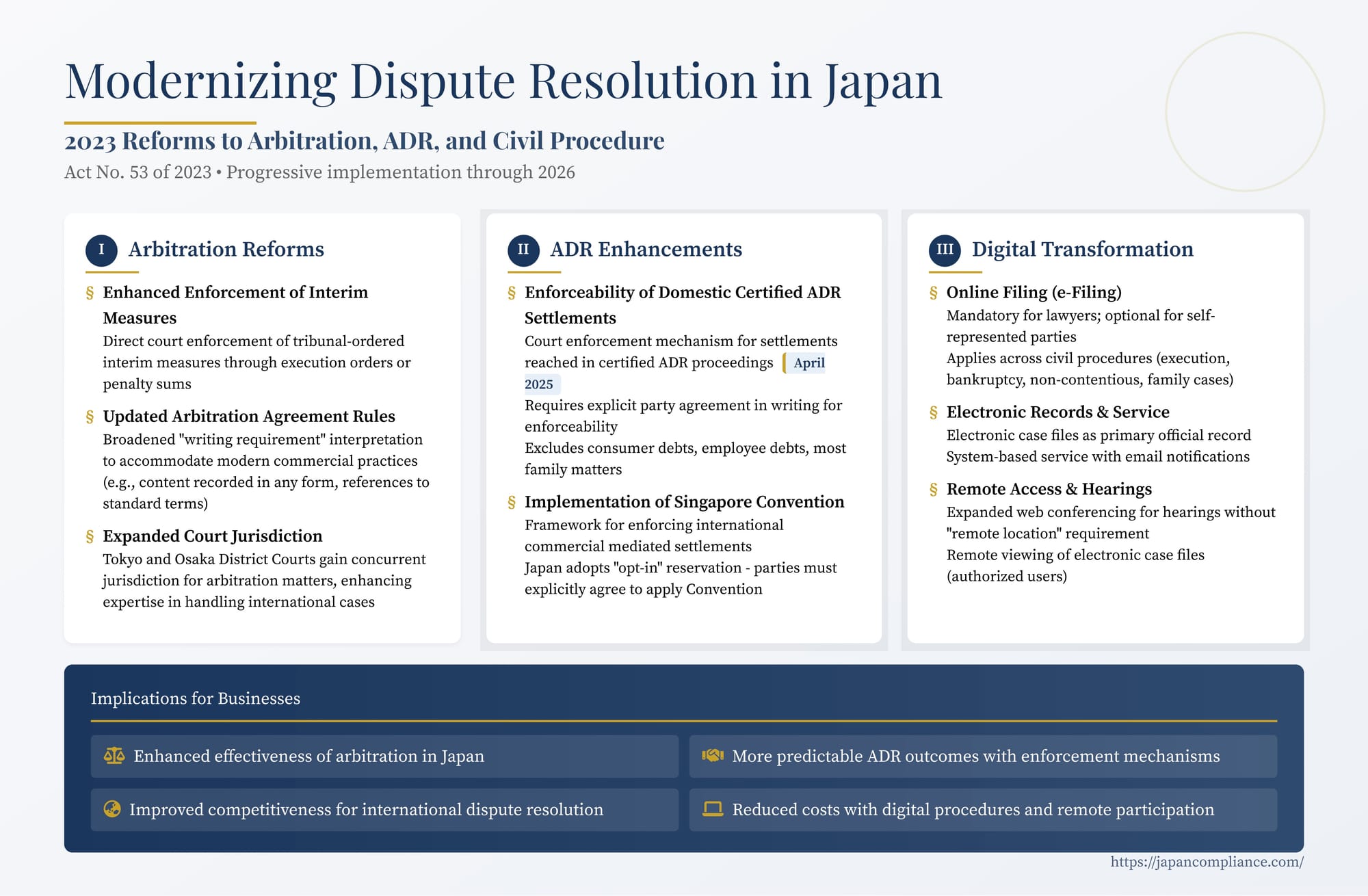

- Japan’s June 2023 reform package aligns the Arbitration Act with the 2006 UNCITRAL Model Law, letting courts enforce arbitral interim measures and expanding Tokyo/Osaka court jurisdiction.

- Certified ADR settlements will soon be directly enforceable, while a new act implements the Singapore Convention, enabling cross-border enforcement of mediated agreements.

- Together with IT-litigation rules due by 2026, these changes make Japan a more attractive, tech-ready seat—but companies must update clauses, templates and internal playbooks.

Table of Contents

- Strengthening Arbitration

- Enhancing ADR and Implementing the Singapore Convention

Japan has embarked on a significant modernization of its legal infrastructure for resolving disputes, aiming to enhance efficiency, align with international standards, and leverage digital technology. Following major revisions to the Code of Civil Procedure in 2022 focused on IT integration in litigation, the Japanese Diet enacted a further package of laws in June 2023 (collectively, Act No. 53 of 2023, alongside Acts Nos. 15, 16, and 17) extending these reforms to arbitration, Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR), and a wide range of other civil and family procedures. These changes, scheduled to take effect progressively (with many key IT components likely aligning with the main civil procedure IT rollout expected by 2026), represent a comprehensive effort to update how legal disputes are managed and resolved. For businesses operating internationally and domestically, these reforms promise greater efficiency but also require adaptation to new processes.

Strengthening Arbitration

Japan's Arbitration Act (仲裁法, Chūsaihō), enacted in 2003, is based on the 1985 UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration. While providing a solid foundation, the need for updates reflecting international developments, particularly the 2006 amendments to the UNCITRAL Model Law, became apparent. The 2023 revisions address key areas to enhance the attractiveness and effectiveness of arbitration seated in Japan.

1. Enforcement of Interim Measures:

- The Challenge: A significant limitation of the previous Arbitration Act was the lack of a mechanism for Japanese courts to directly enforce interim measures (暫定保全措置命令, zantei hozen sochi meirei) ordered by an arbitral tribunal. While tribunals could issue such orders (e.g., to preserve assets or evidence), parties seeking enforcement often had to initiate separate, duplicative provisional remedy proceedings in court, undermining the speed and efficiency of arbitration.

- The Solution: The revised Act introduces a framework (primarily in new Article 49-5) allowing courts to enforce interim measures issued by arbitral tribunals (whether seated in Japan or abroad, subject to reciprocity). This aligns Japanese law with the 2006 UNCITRAL Model Law amendments.

- Types of Measures: The Act explicitly covers various types of interim measures mirroring the Model Law, including orders to maintain or restore the status quo, prevent actions likely to cause harm or prejudice the arbitral process, preserve assets needed to satisfy a subsequent award, and preserve relevant evidence (Revised Arbitration Act, Art. 24(1)).

- Enforcement Mechanisms: Two primary methods for court enforcement are established:

- For measures requiring specific actions (like restoring property or continuing performance under a contract – typically related to Art. 24(1)(iii)), the court can issue an "execution order" (執行決定, shikkō kettei) allowing direct enforcement (e.g., substitute performance).

- For measures prohibiting certain actions (like asset disposal or evidence destruction – typically related to Art. 24(1)(i), (ii), (iv), (v)), the court can, upon finding a breach or likely breach, issue an order requiring the payment of a penalty sum (間接強制金, kansetsu kyōseikin, akin to indirect compulsion) for non-compliance. This penalty order itself becomes enforceable.

- Court Review: The court's role is primarily to assess limited grounds for refusal of enforcement (similar to those for refusing enforcement of arbitral awards, e.g., public policy, procedural fairness issues), rather than re-examining the merits of the interim measure itself.

- Impact: This is arguably the most significant change, making interim relief granted within arbitration potentially much more effective and reducing the need for parallel court proceedings.

2. Arbitration Agreements:

- The requirement for an arbitration agreement to be in writing (Article 13) is maintained, but clarifications were added (Revised Article 13(6)) to explicitly accommodate modern commercial practices. For instance, an agreement can satisfy the writing requirement if its content is recorded in any form, or if a contract refers to a separate document (like standard terms) containing an arbitration clause, making that clause part of the contract. This aligns with the broader interpretation under the 2006 Model Law Option I.

3. Expanded Court Jurisdiction:

- To enhance expertise and efficiency in handling arbitration-related matters (e.g., challenges to awards, enforcement decisions), the revised Act grants concurrent jurisdiction to the Tokyo and Osaka District Courts, alongside the courts previously designated based on party location or the arbitral seat (Revised Arbitration Act, Art. 5(5)). This allows parties to bring cases before courts with potentially greater experience in complex commercial and international arbitration matters. Provisions for discretionary transfer between competent courts are also included.

Enhancing ADR and Implementing the Singapore Convention

Alongside arbitration, the reforms aim to bolster the use and effectiveness of ADR, particularly mediation.

1. Enforcement of Domestic Certified ADR Settlements:

- Background: Japan's ADR Act (Act for Promotion of Use of Alternative Dispute Resolution - 裁判外紛争解決手続の利用の促進に関する法律, Saibangai Funsō Kaiketsu Tetsuzuki no Riyō no Sokushin ni Kansuru Hōritsu) established a system for certifying private ADR providers who meet certain standards. However, settlement agreements reached through these certified procedures previously lacked direct enforceability; parties had to file a separate lawsuit to enforce the settlement if one party failed to comply.

- The Solution: The revised ADR Act (effective April 2025) introduces a mechanism for court enforcement of certain settlement agreements (tokutei wakai) reached in certified ADR proceedings (Revised ADR Act, Art. 27-2).

- Requirements: Enforcement requires that the settlement agreement pertains to a civil dispute, is capable of execution, and importantly, that the parties have explicitly agreed in writing that the settlement can be subject to civil execution.

- Exclusions: Certain types of disputes are excluded from this enforcement mechanism, notably consumer contract disputes (where the consumer is the debtor), individual labor disputes (where the employee is the debtor), and most family disputes (divorce, etc.). However, an exception is made for agreements concerning monetary claims related to family matters, such as child support or alimony, allowing their enforcement through this streamlined process.

- Procedure: Similar to the enforcement of international mediated settlements (see below), a party seeks an "execution order" from the court, which reviews the agreement for specific refusal grounds (e.g., invalidity of the settlement, public policy violations) before granting enforceability.

- Impact: This provides a significant boost to the value of using certified ADR providers in Japan for certain types of disputes, as settlements can now achieve near-judgment finality without requiring a separate enforcement lawsuit, provided the parties agree to it.

2. Implementation of the Singapore Convention on Mediation:

- Background: The UN Convention on International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation (the "Singapore Convention") creates a harmonized framework for the cross-border enforcement of mediated settlement agreements in international commercial disputes. Japan ratified the Convention, and the 2023 legislative package includes the enabling act: the "Act on Special Measures concerning the Implementation Procedures for International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation" (国際的な和解合意に関する国際連合条約の実施に関する法律, Kokusai-teki na Wakai Gōi ni Kansuru Kokusai Rengō Jōyaku no Jisshi ni Kansuru Hōritsu, or 調停条約実施法, Chōtei Jōyaku Jisshihō).

- Key Features:

- Scope: Applies to written settlement agreements resulting from mediation resolving an international commercial dispute. "International" is defined based on parties having places of business in different states or the place of performance/subject matter being outside the parties' states. "Commercial" excludes consumer, family, inheritance, and employment disputes.

- Enforcement Mechanism: Allows a party to apply to a competent Japanese court (Tokyo or Osaka District Courts have concurrent jurisdiction) for an execution order based on the international mediated settlement agreement.

- Refusal Grounds: The court will grant enforcement unless specific grounds for refusal, mirroring those in Article 5 of the Singapore Convention, are proven by the resisting party (e.g., party incapacity, invalid settlement agreement, mediator misconduct, settlement is not final/binding, public policy violation).

- Japan's Reservation: Japan has invoked the "opt-in" reservation under Article 8(1)(b) of the Convention. This means the Convention (and thus the implementing Act) will only apply if the parties to the settlement agreement have explicitly agreed that the Convention shall apply to their settlement.

- Impact: This makes Japan a more attractive venue for international mediation by providing a streamlined path to enforce resulting settlements, enhancing predictability and reducing costs compared to enforcing settlements as standard contracts. However, parties must remember to include the necessary "opt-in" clause in their settlement agreements for the framework to apply in Japan.

Digital Transformation Across Civil Procedures

Building upon the 2022 Code of Civil Procedure revisions, the 2023 laws extend IT integration to a wide array of related procedures, aiming for a largely paperless system.

Key Changes Common Across Procedures:

- Online Filing (e-Filing): Petitions, motions, briefs, and evidence can generally be filed electronically through a dedicated court portal (事件管理システム, jiken kanri shisutemu - Case Management System). Filing online becomes mandatory for lawyers and certain other representatives, while optional for pro se litigants.

- Electronic Case Records (e-Records): Court records will be created and maintained primarily in electronic format. Documents filed electronically are stored directly, while paper filings are scanned and uploaded by court clerks (with exceptions for sensitive information or documents difficult to digitize). Court-generated documents (orders, judgments, hearing records/調書 chōsho) will also be created and stored electronically.

- Electronic Service (e-Service): Service of documents will increasingly utilize the case management system ("system service"). Parties (especially mandatory e-filers) register contact details (like email) and are notified when a document is made available for download/viewing on the system. Service is deemed effective upon download or after a set period (e.g., one week) from notification if not accessed. Traditional service methods remain for parties not using the system.

- Remote Access and Hearings (e-Court): Provisions for remote viewing of electronic case files (subject to authorization) are included. The use of web conferencing for hearings (審尋, shinjin; or 口頭弁論, kōtō benron, where applicable) is significantly expanded, generally removing the previous requirement for parties to be in a "remote location" and allowing participation via web conference when deemed appropriate by the court, often after hearing the parties' opinions. Telephone conferencing remains an option in some less complex procedures or where web conferencing is not feasible.

Specific Procedural Applications:

- Civil Execution & Preservation: Online filing of execution/preservation petitions, electronic seizure orders, electronic management of distribution tables (配当表, haitōhyō), and potentially online access to enforcement information. Mandatory e-filing applies to lawyers representing parties. The need to physically submit certain documents like certified judgments or real estate registration certificates may be eliminated if verifiable through the system.

- Bankruptcy & Insolvency Procedures: Online filing of petitions and creditor claims, electronic creation of key documents like the list of creditors (債権者表, saikenshahyō), and the possibility of conducting creditors' meetings remotely. Court-appointed trustees/administrators (e.g., 破産管財人, hasan kanzainin) are subject to mandatory e-filing.

- Non-Contentious, Mediation, Labor Tribunal, Personnel, Family Cases: Similar IT integration applies, including e-filing, e-records, and expanded web conferencing options. However, specific rules address the heightened privacy and sensitivity concerns in these areas. For example, access to electronic records in family cases remains tightly controlled, often requiring specific court permission even for parties, and exceptions to full electronic conversion of paper documents exist for highly sensitive materials. Procedures like forming mediation agreements or confirming labor tribunal judgments can also occur electronically.

Implications and Outlook

This comprehensive package of reforms represents a major push to modernize Japan's dispute resolution infrastructure.

- Potential Benefits: The changes promise increased efficiency, potentially reduced costs (less paper, travel), improved access to justice (especially via remote participation), greater transparency in some procedures (like special permission to stay), and better alignment with international best practices in arbitration and mediation enforcement. The ability to enforce arbitral interim measures and international mediated settlements directly in Japan is a significant enhancement for international commerce.

- Challenges and Adaptation: Successful implementation hinges on the robust development and user-friendliness of the court's Case Management System. Ensuring cybersecurity and data privacy within the electronic system is paramount. There will be an adaptation period for courts, lawyers, and parties to become proficient with the new digital workflows. Addressing the digital divide to ensure those uncomfortable with or lacking access to technology are not disadvantaged remains crucial. The precise interpretation and application of new concepts, like the grounds for refusing enforcement of mediated settlements or the practicalities of online hearings in various contexts, will evolve through practice and further judicial interpretation.

Overall, these 2023 reforms signal Japan's commitment to creating a more efficient, accessible, and internationally competitive legal environment for resolving disputes. While full implementation will take time, businesses and their legal advisors should begin familiarizing themselves with these new frameworks and preparing for the transition to more digitized dispute resolution processes in Japan.

- Rethinking Defensive Measures: Hostile Takeovers Under Japan’s 2023 METI Guidelines

- Navigating Cyber Incidents in Japan: APPI Compliance & Cybersecurity Basics Explained

- Post-Pandemic Japanese Labor Law: Dismissal, Relocation & Side-Job Pitfalls Explained

- Ministry of Justice – Outline of 2023 Arbitration & ADR Reform (Japanese PDF)

- JIDRC – Practical Guide to Japan-Seated Arbitration (English)