Japan’s Supreme Court Affirms Ban on Mixed Medical Care – Key Takeaways from the 2011 Judgment

TL;DR

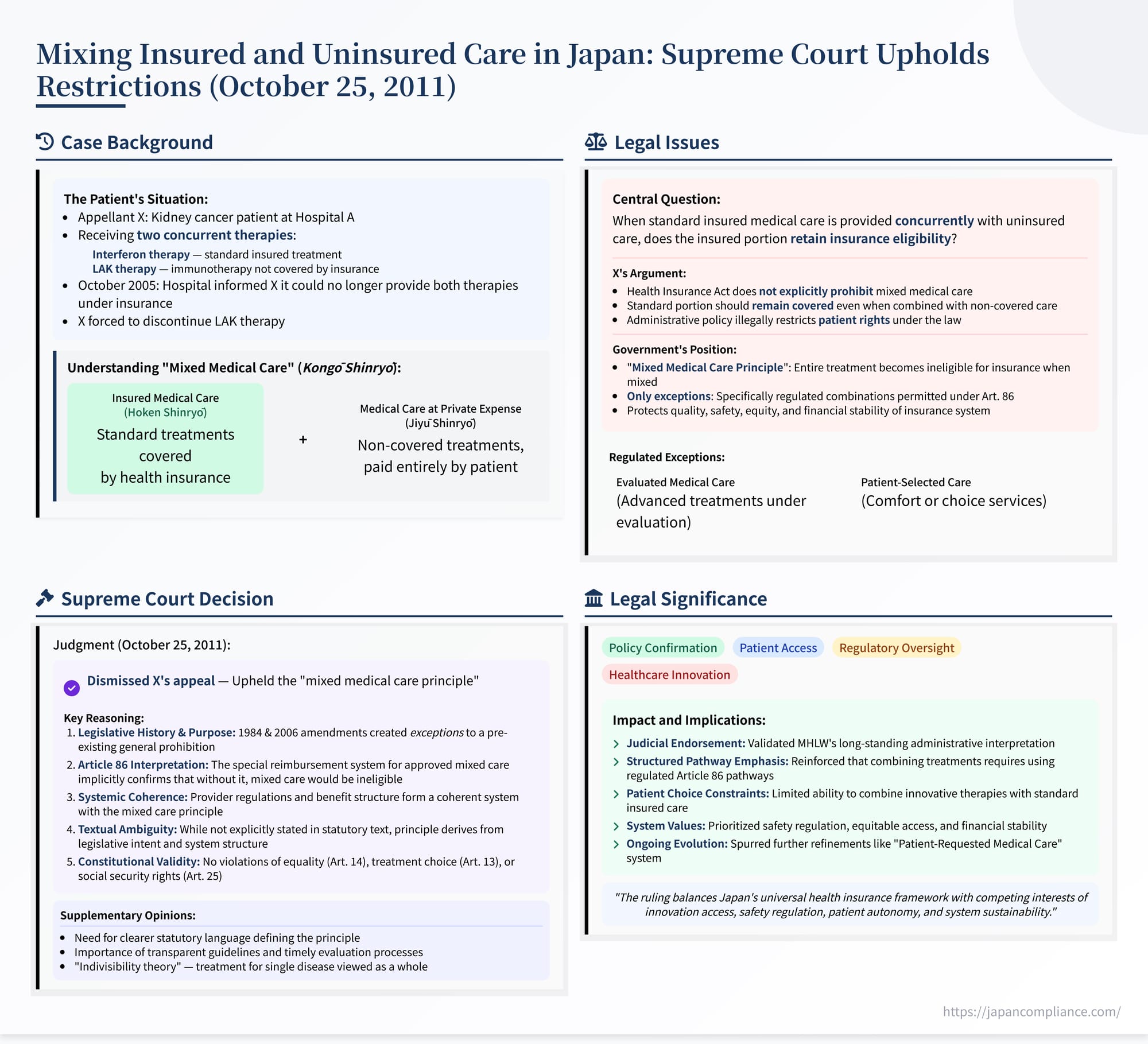

- In 2011 Japan’s Supreme Court confirmed that combining insured and uninsured treatments (“mixed medical care”) generally voids health‑insurance benefits unless strict Article 86 exceptions apply.

- The Court grounded its reasoning in legislative history, system coherence and patient‑safety considerations, rejecting constitutional challenges.

- The decision reinforces regulated pathways (evaluated medical care, patient‑selected care) and limits patients’ ability to obtain public coverage for experimental therapy alongside standard care.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: A Cancer Patient's Treatment Dilemma

- The Legal Challenge: Confirming the Right to Benefits in Mixed Care

- The “Mixed Medical Care Principle” and Legislative Context

- The Supreme Court's Analysis (October 25 2011)

- Supplementary Opinions

- Implications and Significance

- Conclusion

On October 25, 2011, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment clarifying the rules surrounding "mixed medical care" (混合診療 - kongō shinryō) under the country's Health Insurance Act (Case Nos. 2010 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 19 / 2010 (Gyo-Hi) No. 19). The case, titled "Health Insurance Benefit Right Confirmation Case," addressed the fundamental question of whether standard medical treatments covered by health insurance retain their insured status when provided concurrently with treatments not covered by insurance. The Court upheld the long-standing administrative interpretation that, outside specific legal exceptions, combining insured and uninsured care renders the entire episode ineligible for insurance benefits. This decision has profound implications for patient access to advanced or alternative therapies alongside standard care within Japan's universal health insurance system. This analysis examines the case's background, the legal framework, the Supreme Court's reasoning, and the broader significance of the ruling.

Factual Background: A Cancer Patient's Treatment Dilemma

The appellant, X, an individual insured under Japan's Health Insurance Act (HIA), was undergoing treatment for kidney cancer at Hospital A (the Kanagawa Prefectural Cancer Center), an accredited insurance medical institution. The treatment regimen involved two distinct therapies administered concurrently:

- Interferon Therapy: A standard treatment for kidney cancer which, if provided alone, qualifies as "Medical Care Benefits" (療養の給付 - ryōyō no kyūfu) fully covered by the HIA (subject to patient co-payments). This is often referred to as standard "insured medical care" (保険診療 - hoken shinryō).

- LAK Therapy (Lymphokine-Activated Killer cell therapy): An immunotherapy which, at the relevant time, was not covered as a standard Medical Care Benefit and did not qualify under the specific exceptions for advanced or experimental treatments that allow for partial insurance coverage. This type of non-covered treatment is generally termed "medical care at private expense" or "free medical care" (自由診療 - jiyū shinryō).

The combination of these two types of therapy constituted "mixed medical care" (kongō shinryō).

In October 2005, Hospital A informed X that it could no longer continue providing the combined Interferon and LAK therapy regimen under the health insurance system. The hospital cited the prevailing interpretation and administrative guidance from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW). This administrative position, often termed the "principle prohibiting insurance coverage for mixed medical care" (混合診療保険給付外の原則 - kongō shinryō hoken kyūfu-gai no gensoku), holds that when insured medical care is combined with uninsured medical care, the entire course of treatment for that specific illness episode becomes ineligible for any insurance benefits – including the portion that would normally be covered (like the Interferon therapy) – unless the mixed care falls within specific, legally defined exceptions (discussed later).

Faced with this, X was forced to discontinue the LAK therapy component at Hospital A, although X expressed a desire to continue receiving both therapies combined as previously administered.

The Legal Challenge: Confirming the Right to Benefits in Mixed Care

Believing the MHLW's interpretation and the resulting administrative practice to be contrary to the Health Insurance Act and potentially unconstitutional, X filed a lawsuit against the State (Y, representing the government). The suit was framed as an action for confirmation concerning a legal relationship under public law (公法上の法律関係に関する確認の訴え - kōhōjō no hōritsu kankei ni kansuru kakunin no uttae).

X specifically sought a declaratory judgment confirming that, even when receiving mixed medical care (Interferon + LAK therapy), X possessed the legal status and right under the HIA to receive "Medical Care Benefits" (ryōyō no kyūfu) for the portion of the treatment corresponding to standard insured care (the Interferon therapy). Essentially, X argued that the standard care component should remain covered by insurance regardless of its combination with an uncovered therapy.

Lower Court Rulings: The Tokyo District Court initially ruled in favor of X, finding that the HIA did not explicitly support the principle prohibiting coverage for the insured portion of mixed medical care. However, the Tokyo High Court reversed this decision, upholding the MHLW's interpretation and dismissing X's claim. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The "Mixed Medical Care Principle" and Legislative Context

The core of the dispute revolved around the validity and legal basis of the "mixed medical care principle." This principle dictates that, as a general rule, the Japanese health insurance system does not permit the simultaneous provision of insured services and uninsured services within the same course of treatment for a single condition. If such mixing occurs, the entire treatment package, including the otherwise-covered components, falls outside the scope of insurance benefits.

This principle is not explicitly stated in a single article of the HIA. However, its existence has been a long-standing administrative interpretation by the MHLW, underpinning the regulation of healthcare services. The rationale often cited includes:

- Ensuring medical safety and efficacy by limiting coverage to approved treatments.

- Preventing potential abuses where patients might be unduly pressured into accepting expensive, unproven therapies alongside necessary standard care.

- Maintaining fairness and equity in access to care under a universal insurance system, avoiding situations where ability to pay for supplemental non-covered services dictates access to enhanced (or even standard) care.

- Managing the financial resources of the public health insurance system.

Legislative Exceptions: Crucially, the Japanese legislature has created specific, regulated exceptions to this general prohibition. These exceptions allow certain types of non-standard care to be combined with standard insured care, with the standard care portion being covered by a special type of cash benefit reimbursement, while the patient pays the full cost of the non-standard portion.

- Specified Medical Care Costs (tokutei ryōyōhi): Introduced by a 1984 HIA amendment (and applicable under the "Old HIA" - 旧法 kyūhō - relevant to the earlier part of X's treatment), this covered combinations involving specific "patient-selected services" (like private hospital rooms, certain dental materials) and certain "highly advanced medical care" provided at specifically approved institutions.

- Insurance Medical Services Costs for Patient-Selected Services (hokengai heiyō ryōyōhi): Introduced by a 2006 HIA amendment (replacing the tokutei ryōyōhi system and applicable under the current HIA - 法 hō), this refined and expanded the exceptions. It covers combinations involving:

- "Evaluated Medical Care" (評価療養 - hyōka ryōyō): Treatments using advanced medical technology undergoing evaluation for potential future inclusion as standard insured care.

- "Patient-Selected Care" (選定療養 - sentei ryōyō): Services primarily related to patient comfort or choice, such as private rooms, appointments outside standard hours, or certain approved non-standard dental procedures.

These regulated systems (governed primarily by HIA Article 86) allow for flexibility and access to certain non-standard options within a controlled framework, ensuring transparency and preventing the full disqualification of standard care benefits in these specific, approved scenarios. The LAK therapy received by X did not fall under these exceptions at the relevant time.

The Supreme Court's Analysis (October 25, 2011)

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated October 25, 2011, dismissed X's appeal and upheld the mixed medical care principle as a valid interpretation of the HIA. The Court's reasoning was multi-layered, focusing on legislative history, statutory interpretation, systemic coherence, and constitutional considerations.

1. Legislative History and Purpose:

The Court meticulously reviewed the legislative history leading to the 1984 (tokutei ryōyōhi) and 2006 (hokengai heiyō ryōyōhi) amendments. It noted that prior to 1984, regulations under the HIA generally prohibited combining insured and non-insured services, and issues like uncontrolled balance billing for dental materials and private rooms had become significant social problems. The Court concluded that the legislative intent behind creating the tokutei ryōyōhi and hokengai heiyō ryōyōhi systems was precisely to provide regulated exceptions to a pre-existing, albeit unwritten, general principle that mixed medical care was outside the scope of insurance benefits. The parliamentary debates and explanatory materials surrounding these amendments indicated that they were designed on the presumption that the mixed medical care principle was the baseline rule. These systems were created to allow specific, controlled forms of mixed care, not to abolish the underlying general prohibition.

2. Statutory Interpretation of HIA Article 86:

The Court interpreted the language of Article 86 (governing hokengai heiyō ryōyōhi) as supporting the mixed medical care principle. Article 86(1) states that when an insured person receives "evaluated medical care or patient-selected care," the insurer shall provide hokengai heiyō ryōyōhi for "the costs required for that medical care." Article 86(2) specifies how the amount is calculated, referencing the standard fee calculation methods (used for regular ryōyō no kyūfu) and subtracting a co-payment equivalent.

The Court reasoned that the phrase "that medical care" (その療養 / 当該療養 - sono ryōyō / tōgai ryōyō) in Article 86 refers to the entire episode of care received by the patient, encompassing both the non-standard (evaluated or selected) component and the standard insured component provided concurrently. The subsequent calculation focuses primarily on the value of the standard insured component within that episode to determine the amount of the cash reimbursement (hokengai heiyō ryōyōhi). This structure, the Court argued, implicitly acknowledges that without this specific Art. 86 mechanism, the standard component would not be covered when mixed with non-approved uninsured care.

3. Systemic Coherence and Provider Regulations:

The Court emphasized the need for a coherent interpretation of the entire HIA system. Japan's primary insurance benefit is "Medical Care Benefits" (ryōyō no kyūfu), provided in-kind (Art. 63), where patients typically only pay a co-payment. The hokengai heiyō ryōyōhi under Art. 86 is an exceptional cash benefit. The Court argued that allowing the standard portion of unregulated mixed care to remain covered as an in-kind benefit under Art. 63 would render the exceptional cash benefit system of Art. 86 largely meaningless or structurally inconsistent. Why create a specific cash benefit system for the standard portion of approved mixed care if the standard portion of any mixed care was already covered in-kind?

Furthermore, the Court linked the principle to the Ryōyō Tantō Kisoku (Rules for Insurance Medical Care Organs and Doctors), which generally prohibit providers from using unapproved therapies or drugs (Rule 18, 19) and from charging patients more than the standard co-payment (Rule 5), except within the regulated framework of Art. 86 (Rules 5, 5-4). Upholding the mixed medical care principle aligns with these provider-side regulations, reinforcing the goal of limiting healthcare delivery under the insurance system to approved, safe, and effective treatments, and preventing unregulated extra billing.

4. Acknowledgment of Textual Ambiguity:

While strongly endorsing the principle based on legislative history, purpose, and systemic coherence, the Court did acknowledge that the principle is "difficult to say that it is immediately derived solely from the text of Article 86" and that its "purport is not necessarily clearly indicated in the text of the provisions." However, it maintained that the interpretation consistent with the principle could be derived when viewing the HIA system as a whole.

5. Constitutional Validity:

The Court addressed X's constitutional challenges, finding the mixed medical care principle compatible with the Japanese Constitution.

- Article 14(1) (Equality): The Court found no unreasonable discrimination. It held that differentiating between purely insured treatment and mixed treatment, and imposing conditions (like meeting Art. 86 requirements) for covering the latter, has a rational basis related to ensuring medical quality, safety, and managing the insurance system.

- Article 13 (Right to Life, Liberty, Pursuit of Happiness / Treatment Choice): The Court held that the principle does not unduly infringe upon a patient's freedom to choose treatment. While the system restricts insurance coverage for certain combinations, it doesn't prohibit patients from seeking non-covered care entirely at their own expense. Reasonable restrictions on the scope of public insurance benefits are permissible.

- Article 25 (Right to Minimum Standards of Wholesome and Cultured Living / Social Security): Citing established precedents (like the Asahi and Horiki cases), the Court reiterated that the legislature has broad discretion in designing social security systems. The specific structure of insurance benefits, including the limitations imposed by the mixed medical care principle, was deemed not to be "markedly lacking in rationality" as a policy choice balancing various societal interests (patient needs, safety, equity, financial sustainability).

Therefore, the Court concluded that the interpretation of the HIA incorporating the mixed medical care principle did not violate the Constitution.

Supplementary Opinions

The judgment included several supplementary and concurring opinions from individual Justices. While agreeing with the final decision to dismiss the appeal, some opinions expressed reservations or added emphasis:

- One opinion highlighted the lack of explicit textual basis for the principle in the HIA, suggesting legislative clarification would be desirable for legal certainty, especially given the significant impact on patients and providers.

- Another focused on the need for clear guidelines on what constitutes prohibited "mixing," particularly in complex cases involving multiple conditions or providers, to avoid ambiguity and potential "chilling effects" on appropriate care.

- Concerns were raised about the breadth of discretion granted to the MHLW in determining which treatments qualify for the hokengai heiyō ryōyōhi exceptions (especially "evaluated medical care"), emphasizing the need for transparent, timely, and scientifically sound evaluation processes to ensure patient access to beneficial new technologies.

- One opinion elaborated on the underlying logic, suggesting a principle of "indivisibility" (不可分一体論 - fukabun ittai ron) where treatment for a single disease is viewed as a whole, making it logical that introducing a non-covered element affects the insurance status of the entire episode.

Implications and Significance

The 2011 Supreme Court decision solidified the legal standing of the "mixed medical care principle" in Japan, with significant consequences:

- Confirmation of Administrative Practice: It provided judicial endorsement for the MHLW's long-standing interpretation, lending legal weight to administrative guidance restricting unregulated mixed care.

- Reinforcement of Regulated Pathways: It underscores that the only way to receive any health insurance benefit when combining standard care with non-standard care is through the specific, regulated pathways defined under HIA Article 86 (i.e., approved "evaluated medical care" or "patient-selected care").

- Limitations on Patient Choice (within Insurance): While not prohibiting patients from seeking any treatment outside the insurance system entirely at their own expense, the ruling limits their ability to combine desired non-covered treatments with standard insured care and receive insurance benefits for the standard part.

- Emphasis on Safety, Equity, and Finance: The decision reflects a policy orientation prioritizing the integrity, safety standards, equitable access, and financial stability of the universal health insurance system over allowing unrestricted mixing of insured and uninsured services.

- Ongoing Policy Debate: Despite the legal clarification, the ruling did not end the policy debate surrounding mixed medical care. Discussions continue regarding the optimal balance between ensuring access to innovative treatments, patient autonomy, safety regulation, and the sustainability of the public insurance system. Subsequent reforms, like the introduction of the "Patient-Requested Medical Care" (患者申出療養 - kanja mōshide ryōyō) system, represent ongoing efforts to refine the boundaries and procedures within this framework.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's October 25, 2011 judgment confirmed that, under Japan's Health Insurance Act, combining standard insured medical care with uninsured care generally disqualifies the entire treatment episode from insurance benefits, unless the specific requirements for exceptions like "evaluated medical care" or "patient-selected care" under Article 86 are met. While acknowledging the lack of explicit statutory language, the Court derived this "mixed medical care principle" from legislative history, purpose, and the overall structure of the insurance system, finding it both consistent with the Act and constitutionally permissible. The ruling highlights the central role of regulated pathways in managing the interface between standard insured care and medical innovation or patient preferences within Japan's universal healthcare framework.

- Under What Circumstances Can a Japanese Medical Corporation be Dissolved, and What Approvals are Necessary?

- Workers' Comp vs. Consolation Money: Japan's Supreme Court Separates Financial and Non‑Financial Damages (December 1 1966)

- Who Qualifies as a “Medium to Long‑Term Resident” in Japan and How Does the Residence Card System Work?