Mixed Medical Care in Japan: Supreme Court Upholds Restrictions on Health Insurance Coverage

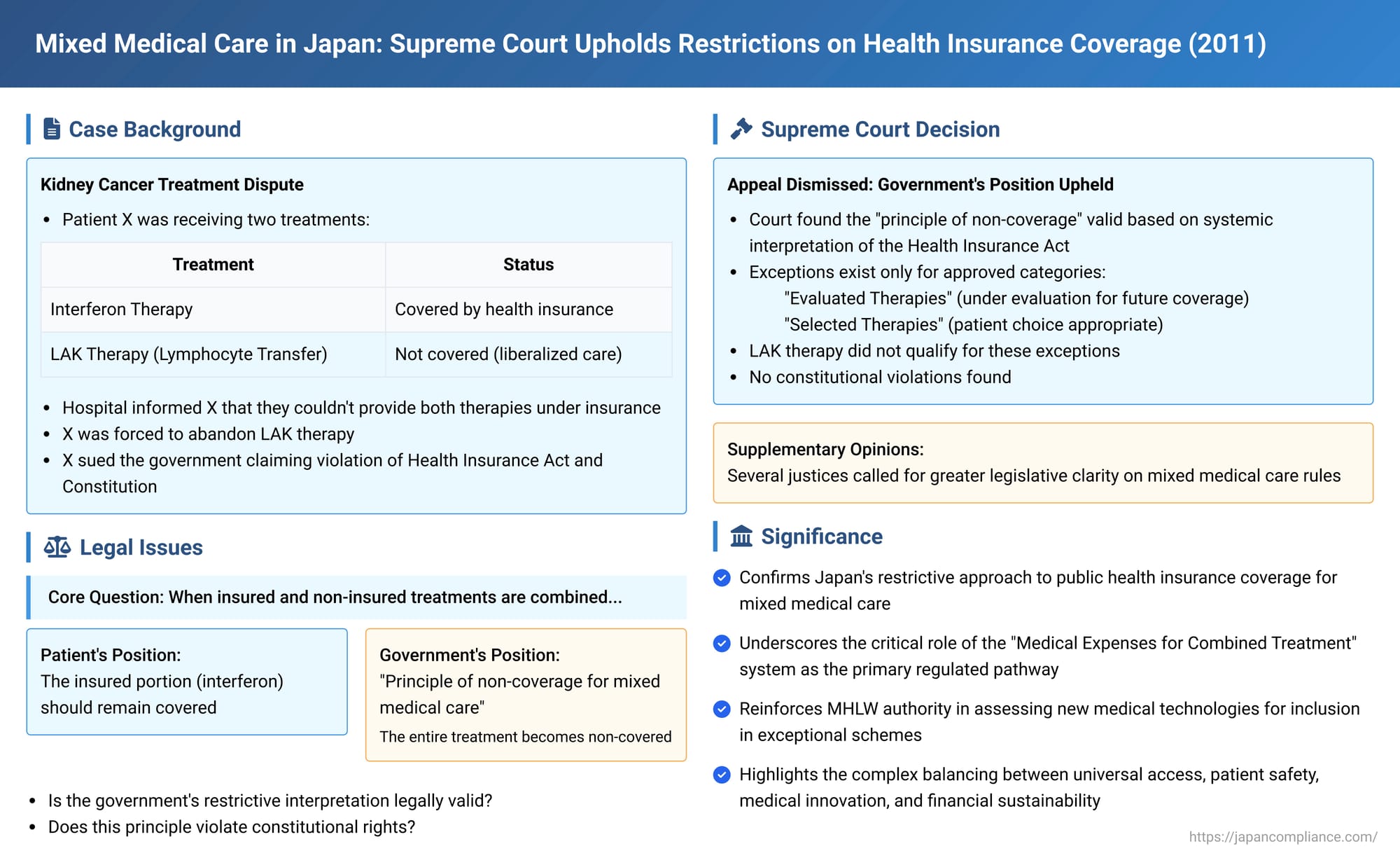

"Mixed medical care" (kongō shinryō)—the practice of combining medical treatments covered by public health insurance with those that are not (such as advanced or experimental therapies)—has long been a contentious issue in Japan's healthcare system. A central question is whether the portion of care that would normally be insured remains covered when mixed with non-insured treatments. On October 25, 2011, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment (Heisei 22 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 19, Heisei 22 (Gyo-Hi) No. 19) addressing this, ultimately upholding the government's restrictive stance.

The Patient's Dilemma: Kidney Cancer Treatment and an Insurance Hurdle

The plaintiff, X, a beneficiary of Japan's public health insurance system, was receiving treatment for kidney cancer at an insurance-designated hospital. The treatment plan involved a combination of:

- Interferon therapy, which, if administered alone, would qualify as standard insured medical care (hoken shinryō) covered by health insurance as a "benefit in kind" (ryōyō no kyūfu).

- LAK therapy (Activated Autologous Lymphocyte Transfer Therapy using Interleukin-2), an advanced treatment considered "liberalized medical care" (jiyū shinryō) and not covered by standard health insurance.

The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) had a long-standing interpretive policy known as the "principle of non-coverage for mixed medical care" (kongō shinryō hoken kyūfu-gai no gensoku). According to this principle, when insured medical care is combined with non-insured medical care in a "mixed medical care" setting, the entire course of treatment, including the part that would normally be insured, generally falls outside the scope of health insurance benefits. Exceptions are made only for specific, legally defined circumstances.

Following this MHLW principle, the hospital informed Plaintiff X that it could not continue providing the combined interferon and LAK therapy under the health insurance scheme. This forced X to abandon the LAK therapy component of the treatment. X subsequently filed a lawsuit against the Japanese government (Y), arguing that the MHLW's interpretation and its application in this manner violated the Health Insurance Act and the Constitution of Japan. X sought a court declaration confirming their right to receive health insurance benefits for the interferon therapy portion, even when it was administered in conjunction with the LAK therapy.

The Tokyo District Court initially ruled in favor of Plaintiff X. However, the Tokyo High Court overturned this decision, dismissing X's claim. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Verdict (October 25, 2011): The Government's Stance Upheld

The Supreme Court dismissed Plaintiff X's appeal, thereby siding with the government and affirming the legality of the "principle of non-coverage for mixed medical care."

Core Reasoning: Systemic Interpretation of the Health Insurance Act

The Court's judgment rested on a comprehensive interpretation of the Health Insurance Act, its legislative history, and its overall systemic design:

- The Principle as a Starting Point: The Court acknowledged that the "principle of non-coverage for mixed medical care" is not explicitly and comprehensively spelled out in the Health Insurance Act for every conceivable situation.

- Exceptional Systems Prove the Rule: However, the Court found that specific systems established within the Act, such as the former "Specified Medical Care Costs" (Tokutei Ryōyōhi) system and the current "Medical Expenses for Combined Treatment with Insurance and Non-Insurance Coverage" (Hokengai Heiyō Ryōyōhi) system (governed by Article 86 of the Act), were designed and legislated with the pre-existing principle of non-coverage for mixed medical care as their underlying premise.

- How the Exceptional Systems Work: These systems allow for a form of insurance coverage (typically a cash reimbursement equivalent to the cost of the insured portion of care) only when standard insured treatments are combined with specific, approved categories of non-insured treatments. These categories are:

- "Evaluated Therapies" (Hyōka Ryōyō): These include advanced medical procedures and technologies that are undergoing evaluation for future inclusion in the standard insurance benefit package (e.g., certain advanced medical care provided at designated institutions, clinical trials).

- "Selected Therapies" (Sentei Ryōyō): These cover services where patient choice is deemed appropriate, such as electing for a private hospital room or certain high-cost dental materials.

- LAK Therapy's Status: The Court noted that LAK therapy, the advanced treatment Plaintiff X was receiving, did not qualify as an approved "evaluated therapy" at the relevant time (it had previously been considered advanced medical care but was later removed from the approved list due to questions about its efficacy).

- Conclusion on Mixed Care: Therefore, the Supreme Court reasoned that when a patient undergoes mixed medical care where the non-insured component (like LAK therapy in this instance) is not one of these specially approved types, the general "principle of non-coverage for mixed medical care" applies. This means the entire course of treatment, including the parts that would be insurable if provided alone (like the interferon therapy), falls outside the scope of health insurance benefits. The Court found that the legislative intent, overall coherence of the Health Insurance Act, and the practical difficulty of separating components of care supported this interpretation, even if the statutory language itself wasn't perfectly explicit on this point.

Constitutional Considerations: No Violation Found

Plaintiff X had also argued that this interpretation violated constitutional rights. The Supreme Court rejected these claims:

- It held that it is permissible for the government to rationally limit the scope of medical services covered by public health insurance, considering the need to ensure the quality, safety, and efficacy of treatments, as well as the financial constraints of the system.

- The "principle of non-coverage for mixed medical care," as interpreted by the Court, was not found to create unreasonable discrimination (contrary to Article 14, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution – equality under the law), nor was it deemed to unjustly infringe upon patients' freedom to choose their medical treatment (related to Article 13 – respect for individuals and the right to pursue happiness).

- Furthermore, the Court concluded that this principle was not conspicuously lacking in rationality as a component of Japan's social security system (related to Article 25 – the right to maintain minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living, and the state's duty to promote social welfare and security). The Court referenced major precedents on legislative discretion in social security matters, such as the Asahi litigation and the Horiki litigation.

The "Why" Behind the Principle: Policy Considerations

The "principle of non-coverage for mixed medical care" is rooted in several policy objectives:

- Ensuring Medical Safety and Efficacy: A primary goal is to ensure that treatments covered or subsidized by the public health insurance system meet established standards of safety and effectiveness. Allowing unregulated mixing could introduce unproven or unsafe therapies into a patient's care regimen while still leveraging public funds for other parts of that care.

- Maintaining Equity ("Public Medical Equality Theory"): Historically, as noted in the commentary, one of the justifications was to prevent a two-tiered system where individuals with greater financial means could access non-insured advanced treatments in conjunction with standard insured care, potentially leading to inequities in access to the benefits of the public insurance system or diverting resources.

- Financial Sustainability of the Insurance System: Controlling the range of services eligible for insurance coverage is essential for managing the costs and ensuring the long-term financial viability of Japan's universal health insurance system.

Calls for Legislative Clarity (Supplementary Opinions)

Despite upholding the government's interpretation, the Supreme Court's judgment included several supplementary opinions from the participating Justices. A common theme in these opinions was the acknowledgment that the "principle of non-coverage for mixed medical care" lacks a clear, explicit, and easily understandable statutory basis for all its applications. Justices, including Justice Tahara, pointed out the complexities and potential for confusion, emphasizing that it would be desirable for the legislature to establish clearer and more explicit rules regarding mixed medical care. Justice Tahara's opinion specifically highlighted the need for clear criteria on how the principle applies in various complex clinical scenarios to avoid "chilling effects" (ishuku shinryō) where medical institutions might hesitate to provide potentially beneficial (even if non-insured) care due to uncertainty about insurance implications.

Implications for Patients and the Healthcare System

The Supreme Court's 2011 decision has significant implications:

- It confirms Japan's generally restrictive approach to public health insurance coverage for mixed medical care. Patients who opt to combine standard insured treatments with advanced or experimental therapies not specifically approved under the "evaluated therapy" or "selected therapy" frameworks risk losing insurance coverage for the standard care components as well.

- It underscores the critical role of the "Medical Expenses for Combined Treatment with Insurance and Non-Insurance Coverage" system (Article 86 of the Health Insurance Act) as the primary regulated pathway for patients to receive some insurance benefits when undergoing mixed medical care. Access to this system depends on the non-insured treatment being officially recognized as an "evaluated therapy" or a "selected therapy."

- The ruling reinforces the authority of the MHLW in the rigorous process of assessing new medical technologies and deciding whether they meet the criteria for inclusion in these exceptional schemes, thereby becoming eligible for partial insurance subsidization when used in combination with standard care.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2011 judgment in the mixed medical care case affirmed the Japanese government's long-standing restrictive policy. While acknowledging the lack of perfectly explicit statutory language to cover every nuance of this principle, the Court found it to be a justifiable interpretation derived from the overall structure, legislative intent, and systemic coherence of the Health Insurance Act. The decision also deemed this policy constitutional. The case highlights the complex balancing act inherent in any universal health insurance system: providing access to necessary and effective care for all, ensuring patient safety, fostering medical innovation, and maintaining financial sustainability, all while navigating the evolving demands and choices of patients seeking the best possible treatments. The calls from within the Court for greater legislative clarity, however, remain a pertinent reminder of the need for transparency in rules that so profoundly affect patient care and access.