Mistakes in Tax Filings: Can Japanese Taxpayers Claim 'Error' to Invalidate Their Returns?

Date of Judgment: October 22, 1964

Case Name: Claim for Revocation of Income Tax Assessment Decision, etc. (昭和38年(オ)第499号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

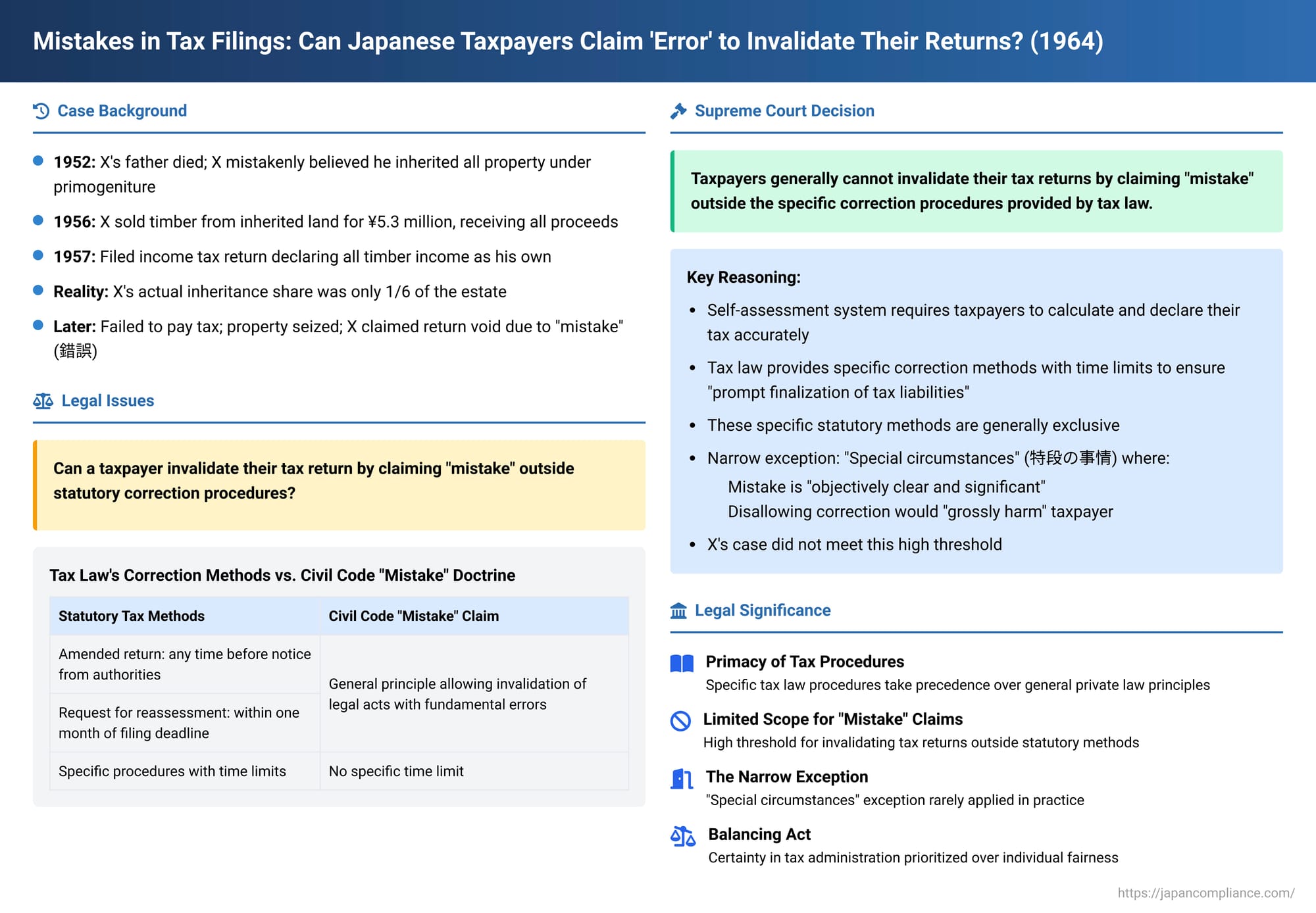

In a foundational judgment delivered on October 22, 1964, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed a critical question regarding the finality of self-assessed tax returns: Can a taxpayer who filed an income tax return based on a fundamental misunderstanding of fact later claim that the entire return is invalid due to this "mistake" (sakugo - 錯誤), particularly when specific statutory procedures for correcting tax returns exist but were not utilized within their prescribed time limits? The Court largely affirmed the principle that statutory correction methods are generally exclusive, setting a high bar for any direct claim of invalidity based on taxpayer error.

The Inheritance Misunderstanding: A Costly Error

The plaintiff, X, was the eldest son of a landowner who had passed away in 1952 (Showa 27). X, being unaware of the then-applicable co-heirship system (共同相続制度 - kyōdō sōzoku seidō) under Japanese inheritance law, mistakenly believed that he, as the eldest son, had inherited all of his father's property under the older system of primogeniture (家督相続 - katoku sōzoku). In reality, the father's assets, including timber on mountain land, were co-inherited by X and two other individuals, with X's actual share being only one-sixth of the estate.

In July 1956, X, acting as the sole seller and presumably under the continued misapprehension that he was the sole owner, sold the timber from the inherited mountain land for a price of ¥5,300,000. He received the entire sales proceeds himself.

Subsequently, on March 12, 1957, X filed his income tax return for the 1956 tax year. Consistent with his mistaken belief, he reported the entire income derived from the timber sale as his own personal income. Based on this declaration, his taxable income was calculated at ¥3,021,200, resulting in an assessed tax of ¥943,480.

X later failed to pay this assessed tax, leading the tax authorities (Y et al., representing the local tax office head and the State) to seize his property to satisfy the tax delinquency. In response, X filed a lawsuit seeking a declaration that the tax seizure was invalid. His central argument was that his 1956 income tax return was fundamentally flawed and should be considered void due to a "mistake of fact concerning an essential element" (法律行為の要素に錯誤がある - hōritsu kōi no yōso ni sakugo ga aru, referencing principles similar to those in Civil Code Article 95 regarding the voidability of private legal acts due to mistake). He contended that he had declared income that, for the most part, did not actually belong to him.

The lower courts (Wakayama District Court and Osaka High Court) both rejected X's arguments and dismissed his claim. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Dilemma: Taxpayer Mistake vs. Finality of Tax Filings

The case presented a fundamental conflict between the desire to correct substantive errors in tax liability and the need for certainty and finality in tax administration, particularly under a self-assessment system. The key legal questions were:

- Does the general private law principle that a legal act can be voided due to a fundamental mistake by one of the parties apply directly to a public law act such as the filing of a self-assessed tax return?

- Are taxpayers restricted to using only the specific correction procedures (and their time limits) provided within the tax statutes to rectify errors in their returns, or can they later seek to invalidate the entire return based on a claim of mistake, especially if those statutory deadlines have passed?

The old Income Tax Act, applicable at the time, did provide specific mechanisms for taxpayers to correct their filed returns:

- If a taxpayer discovered that their declared tax amount was too low, they could file an amended return (修正申告書 - shūsei shinkokusho) at any time before receiving a corrective assessment notice from the tax authorities (Article 27, paragraph 1 of the old Act).

- If a taxpayer discovered that their declared tax amount was too high, they could file a "request for reassessment" (更正の請求 - kōsei no seikyū) with the tax office, but this was subject to a strict time limit – only within one month after the original tax filing deadline (Article 27, paragraph 6 of the old Act).

X had not utilized these specific statutory procedures within the prescribed timeframes to correct his 1956 return.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Statutory Correction Methods are Generally Exclusive

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, affirming the lower courts' decisions. The Court held that a taxpayer generally cannot invalidate their self-assessed tax return by claiming a mistake of fact outside the specific correction procedures provided by the tax law.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Nature of the Self-Assessment System and Its Correction Mechanisms: The Court emphasized that the Income Tax Act adopted a self-assessment system (申告納税制度 - shinkoku nōzei seido). Under this system, the primary responsibility for calculating and declaring taxable income and tax due rests with the taxpayer, who is presumed to be most familiar with their own financial affairs. The Act provided specific, albeit time-limited, procedures (amended returns and requests for reassessment) for correcting errors in these self-assessed declarations.

- Rationale for Limiting Correction Methods: The very reason the Income Tax Act established these particular methods and limitations for correcting self-assessed returns was to serve the "national fiscal necessity of establishing tax liabilities as promptly as possible" (租税債務を可及的速やかに確定せしむべき国家財政上の要請 - sozei saimu o kakyūteki sumiyaka ni kakutei seshimu beki kokka zaiseijō no yōsei). This approach, the Court found, ensures stability in public finances and was also considered not to impose undue hardship on taxpayers, given the availability of these (albeit time-restricted) corrective avenues.

- Exclusivity of Statutory Correction Methods: Therefore, the Court ruled that when it comes to rectifying errors in the content of a filed tax return, taxpayers are generally bound to use the methods specifically provided by the tax law. They cannot ordinarily assert that the return is invalid due to a mistake in its content through means other than these statutory procedures.

- A Narrow Exception for "Special Circumstances": The Supreme Court did, however, acknowledge a very narrow potential exception to this rule of exclusivity. A taxpayer might be permitted to assert a mistake outside the statutory methods if there are "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō) where the mistake is "objectively clear and significant" (客観的に明白且つ重大 - kyakkanteki ni meihaku katsu jūdai), AND where disallowing correction by means other than the prescribed statutory methods would "grossly harm the taxpayer's interests" (納税義務者の利益を著しく害する - nōzeigimusha no rieki o ichijirushiku gaisuru).

- Application to X's Case: The Court found that X's situation did not meet the high threshold for these "special circumstances."

- X did not allege any clerical errors or miscalculations apparent on the face of the tax return itself.

- The record showed that X alone had acted as the seller of the timber and had personally received all the sales proceeds.

- Under these facts, even if X had indeed made a mistake regarding his true inheritance share (a mistake about the legal ownership of the income source), this did not constitute the kind of "special circumstances" that would permit him to claim his entire tax return was invalid due to mistake, bypassing the statutory correction mechanisms.

- Constitutional Argument Dismissed: X had also argued that the lower courts' decisions violated Article 30 of the Constitution (which establishes the duty to pay taxes as provided by law). The Supreme Court dismissed this claim, stating that since the lower courts' interpretation of the Income Tax Act was found to be correct, the constitutional argument, which was predicated on a violation of the Act, lacked a proper foundation.

Analysis and Implications

This 1964 Supreme Court judgment is a landmark decision in Japanese tax procedure and has several enduring implications:

- Primacy of Tax Law Procedures over General Private Law Principles: The ruling clearly establishes that the specific procedures and time limits set forth in tax statutes for correcting self-assessed tax returns generally take precedence over the direct application of general private law principles, such as those allowing for the voiding of a contract due to a fundamental mistake. For errors leading to overpayment, this principle is often referred to by commentators as the "exclusivity of the request for reassessment" (kōsei no seikyū no haitasei).

- Limited Scope for Direct Claims of "Mistake" to Invalidate Tax Filings: Taxpayers generally cannot unwind their filed tax returns by simply claiming they made a mistake, especially after the statutory deadlines for filing an amended return or a request for reassessment have expired. This promotes finality and certainty in tax administration.

- The Very Narrow "Special Circumstances" Exception: The exception carved out by the Court for "special circumstances" involving an "objectively clear and significant" error that would cause "gross harm" if not otherwise correctable is interpreted very narrowly. Legal commentators have noted that this abstractly defines the outer limits of the exclusivity principle, but its practical application is rare. There has been ongoing scholarly debate about what exactly constitutes sufficient "obviousness" (meihakusei) of an error to meet this high bar – for instance, whether it must be apparent on the face of the return itself or if it includes errors that would have been clear had proper investigation been conducted.

- Tension Between Finality and Substantive Fairness: While the ruling prioritizes the need for prompt finalization of tax liabilities for fiscal stability, it can appear harsh in situations where a taxpayer makes a genuine and significant error but misses the relatively short statutory window for correction (which, for requests for reassessment due to overpayment, was only one month after the filing deadline under the old law).

- Relevance in Contemporary Tax Law: Although the specific articles of the Income Tax Act and the Civil Code's provisions on mistake (Article 95) have undergone revisions since 1964, the fundamental principle established by this Supreme Court decision—the general exclusivity of tax law's own correction mechanisms for self-assessed returns—is considered to remain influential in Japanese tax jurisprudence. The underlying rationale of ensuring prompt finality of tax obligations while providing limited, specific avenues for correction continues to shape the interpretation of current tax procedures.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1964 decision in this case is a foundational judgment in Japanese tax procedural law. It establishes that self-assessed tax returns, once filed, are generally binding, and any errors therein must typically be addressed through the specific statutory avenues provided by tax law, such as amended returns or timely requests for reassessment. A direct claim to invalidate a return based on general principles of mistake is permissible only in very exceptional "special circumstances" involving an objectively clear and significant error that would cause gross harm to the taxpayer if left uncorrected through means other than invalidation. This ruling underscores the importance of taxpayer diligence in preparing returns and the general primacy of statutory tax procedures in maintaining the stability and predictability of tax obligations under Japan's self-assessment system.