Mistaken Bank Transfer: Whose Money Is It Anyway? A Japanese Supreme Court View

Date of Judgment: April 26, 1996

Case Name: Third-Party Objection Suit

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

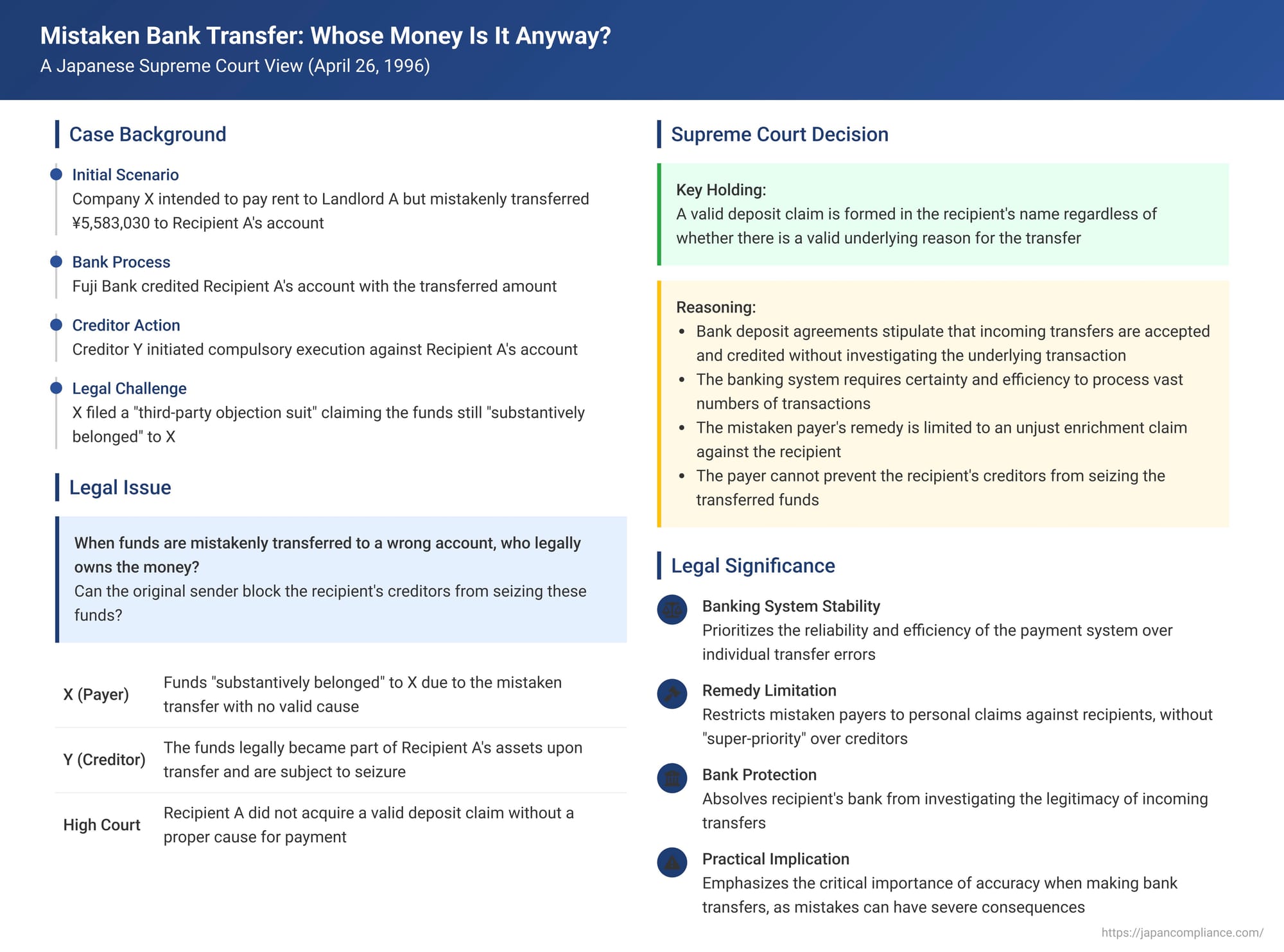

Sending money to the wrong bank account is a common, and often distressing, error in the digital age. When such a mistake occurs, a critical legal question arises: who legally owns the funds once they land in the unintended recipient's account? And what recourse does the person who made the mistaken transfer have, especially if creditors of the unintended recipient attempt to seize those funds? A significant Japanese Supreme Court decision from April 26, 1996, provided a clear, albeit perhaps unsettling for some, answer to these questions, prioritizing the stability of the banking payment system.

A Costly Typo: The Erroneous Bank Transfer

The case unfolded as follows:

- The Intended Transaction: X (a company) intended to pay rent to its landlord, Company A (let's call them "Landlord A"). The payment was supposed to be transferred into Landlord A's bank account at Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank.

- The Mistake: X, however, mistakenly instructed its own bank (Fuji Bank, Ōmori Branch) to transfer a substantial sum of ¥5,583,030 to a different bank account: an account at Fuji Bank, Ueno Branch, belonging to Company A' (let's call them "Recipient A'"). While X had engaged in transactions with Recipient A' in the past, there was no current business relationship between them at the time of the transfer, and X owed no money to Recipient A'. The error was compounded by the fact that the Japanese phonetic renderings of "Landlord A" and "Recipient A'" were identical, likely contributing to the mix-up.

- Funds Credited: Fuji Bank (acting as Recipient A''s bank) duly credited Recipient A''s ordinary deposit account with the transferred amount.

- Creditor's Seizure: Subsequently, Y, who was a creditor of Recipient A', initiated compulsory execution (a seizure) against Recipient A''s Fuji Bank account. This account, at the time of seizure, had a balance of approximately ¥5.72 million, the vast majority of which (the ¥5.58 million) consisted of the funds mistakenly transferred by X.

- Payer's Lawsuit: X (the original payer) filed a "third-party objection suit." This is a legal action under Japan's Civil Execution Act allowing a third party (X) to object to the seizure of property if they claim a right that prevents its transfer or delivery to the seizing creditor (Y). X argued that the mistakenly transferred funds "substantively belonged" to X and should not be available to satisfy Recipient A''s debts to Y.

- Lower Court Rulings: The High Court (and the first instance court) had ruled in favor of X (the payer). The High Court reasoned that for a valid deposit right to be formed in Recipient A''s name as a result of the transfer, there generally needed to be a legitimate underlying legal reason (a "cause") for Recipient A' to receive the funds from X. Since this was a clear mistake and no such cause existed, Recipient A' had not validly acquired a deposit claim against its bank for the mistakenly transferred sum. Therefore, the funds effectively still belonged to X.

Y, the creditor of Recipient A', appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decisive Ruling

The Supreme Court, on April 26, 1996, overturned the High Court's decision. It ruled that Recipient A' did acquire a valid deposit claim against its bank for the mistakenly transferred amount, and therefore X (the payer) could not prevent Y (Recipient A''s creditor) from seizing these funds. X's primary recourse was an unjust enrichment claim against Recipient A'.

Core Rulings of the Supreme Court:

- Deposit Forms Regardless of Underlying Cause between Payer and Recipient:

The Court held that when funds are transferred from a payer into an ordinary deposit account of a recipient at the recipient's bank, a valid ordinary deposit contract for that amount is formed between the recipient and their bank. Consequently, the recipient acquires an ordinary deposit claim (a right to demand the money from the bank) for the transferred amount.

This formation of the deposit claim occurs irrespective of whether a valid underlying legal relationship or cause for payment (e.g., a debt, a purchase) exists between the original payer and the recipient. - Rationale for this Rule:

- Terms of Deposit Agreements: Standard bank deposit agreements (the "ordinary deposit regulations" mentioned by the Court) generally stipulate that incoming funds transferred to an account will be accepted and credited. These agreements do not typically make the validity of the deposit contract between the recipient and their bank conditional upon the existence or validity of any underlying transaction between the payer and the recipient.

- Efficiency and Stability of Payment Systems: Bank transfers are designed to be a safe, inexpensive, and swift method for moving funds. To ensure the smooth and efficient processing of a vast number of high-value transactions, the banking system operates on the principle that intermediary banks do not, and cannot, investigate the existence, validity, or specific details of the underlying legal relationships motivating each fund transfer. Making the validity of a deposit dependent on such external factors would cripple the payment system.

- Payer's Remedy is an Unjust Enrichment Claim against the Recipient:

If, as in this case, funds are transferred without any valid underlying legal reason, and the recipient thereby acquires a deposit claim against their bank for that amount, the original payer (X) may merely acquire an unjust enrichment claim (不当利得返還請求権 - futō ritoku henkan seikyūken) against the recipient (Recipient A') for the mistakenly transferred sum. - Payer Has No Direct Claim on the Deposit Overriding Recipient's Creditors:

Crucially, the Supreme Court stated that the mistaken payer (X) does not acquire a right that would prevent the assignment of the recipient's (Recipient A''s) deposit claim, nor a right that would allow X to block a compulsory execution (seizure) by the recipient's creditors (like Y) against that deposit claim. The payer cannot assert a kind of "super-priority" or "true ownership" over the specific funds once they are validly incorporated into the recipient's bank account balance.

Application to the Facts:

Based on these principles, Recipient A' was deemed to have acquired a valid deposit claim against Fuji Bank for the mistakenly transferred amount. Even though X had no intention of paying Recipient A', X's primary recourse was an unjust enrichment claim against Recipient A'. X could not use a third-party objection suit to stop Y (Recipient A''s creditor) from seizing the funds that were, in the eyes of the banking law, part of Recipient A''s assets (i.e., Recipient A''s claim against Fuji Bank).

Understanding the Implications: A Deeper Dive

This 1996 Supreme Court decision prioritized the objective finality and operational integrity of the bank transfer system over the subjective intentions or errors of individual users in this specific context.

Deposit Formation Mechanics

The ruling affirms that the deposit contract between a recipient and their bank is formed based on the bank's agreement to accept incoming funds (as per its standard terms) and the actual crediting of the account. The "cause" or reason for the transfer between the payer and recipient is external to this recipient-bank relationship for the purpose of deposit formation.

Shift from Some Lower Court Tendencies

Previously, many lower courts had leaned towards the view that if there was no valid underlying reason for the transfer, the recipient didn't truly acquire a right to the deposit, often to protect the mistaken payer. The Supreme Court took a different stance, emphasizing the systemic needs of banking.

The Practical Remedy of "Kumimodoshi" (Reversal)

While the formal legal ruling establishes the recipient's deposit right, in practice, if a mistaken transfer occurs, there is an interbank procedure known as "kumimodoshi" (組戻し) or recall/reversal of the transfer. If the mistaken recipient cooperates and consents, the funds can often be returned to the original payer relatively smoothly. The Supreme Court's decision doesn't negate this practical avenue but addresses the strict legal rights if such cooperation isn't forthcoming or if third-party creditors intervene.

The Payer's Own Error

It was noted in the case background that X (the payer) might have been grossly negligent in providing the wrong account details. While this might have precluded X from voiding their payment instruction to their own bank based on a claim of mistake, the Supreme Court's judgment focused on the separate issue: the formation of the deposit between Recipient A' and Recipient A''s bank.

What About the Mistaken Recipient?

While this judgment formally grants the mistaken recipient (Recipient A') the deposit claim against their bank, it doesn't mean they get a windfall free of consequences.

- Unjust Enrichment: As the Supreme Court stated, Recipient A' is liable to X (the payer) for unjust enrichment.

- Potential Criminal Liability and Abuse of Rights: Subsequent Supreme Court jurisprudence in other cases (e.g., a criminal case from 2003 and a civil case from 2008) has indicated that if a recipient knows funds have been mistakenly transferred into their account, they have a duty to notify their bank. Knowingly withdrawing and spending such funds can constitute fraud. Furthermore, a recipient's attempt to withdraw such funds might be denied by a court as an "abuse of rights" if the circumstances suggest fraudulent intent. So, while the deposit claim is technically formed, the recipient's ability to freely use the mistakenly transferred funds, especially against the interests of the original payer, is significantly constrained by other legal principles.

Protecting the Recipient's Creditors

This 1996 ruling does end up favoring the creditors of the mistaken recipient in a civil execution context, as they can seize the deposit claim which now legally belongs to the recipient. Legal commentators have discussed alternative legal theories that could have, in principle, offered more protection to the mistaken payer (e.g., by constructing a quasi-proprietary claim for the payer over the transferred value, or using trust law concepts), but the Supreme Court, in this civil dispute, did not adopt those approaches, focusing instead on the distinct legal relationships.

Protecting the Recipient's Bank

The decision is highly protective of the recipient's bank (and the banking system generally) by absolving it of the need to investigate the underlying legitimacy of every incoming transfer. This ensures the speed and efficiency of fund transfers.

Conclusion

The 1996 Japanese Supreme Court decision on mistaken bank transfers established a clear, if sometimes stark, rule: once funds are credited to a recipient's bank account, a valid deposit claim is formed in the recipient's name against their bank, regardless of any mistake or lack of underlying debt between the payer and the recipient. The mistaken payer's primary legal remedy is to pursue an unjust enrichment claim against the person who received the funds. They generally cannot directly intervene to reclaim the specific deposit from the recipient's bank account if, for example, a creditor of the recipient seeks to seize it. This ruling underscores the high premium placed on the certainty and efficiency of electronic payment systems, while directing mistaken payers to a personal claim against the unintended beneficiary for recovery. It serves as a strong reminder of the critical importance of accuracy when initiating any bank transfer.