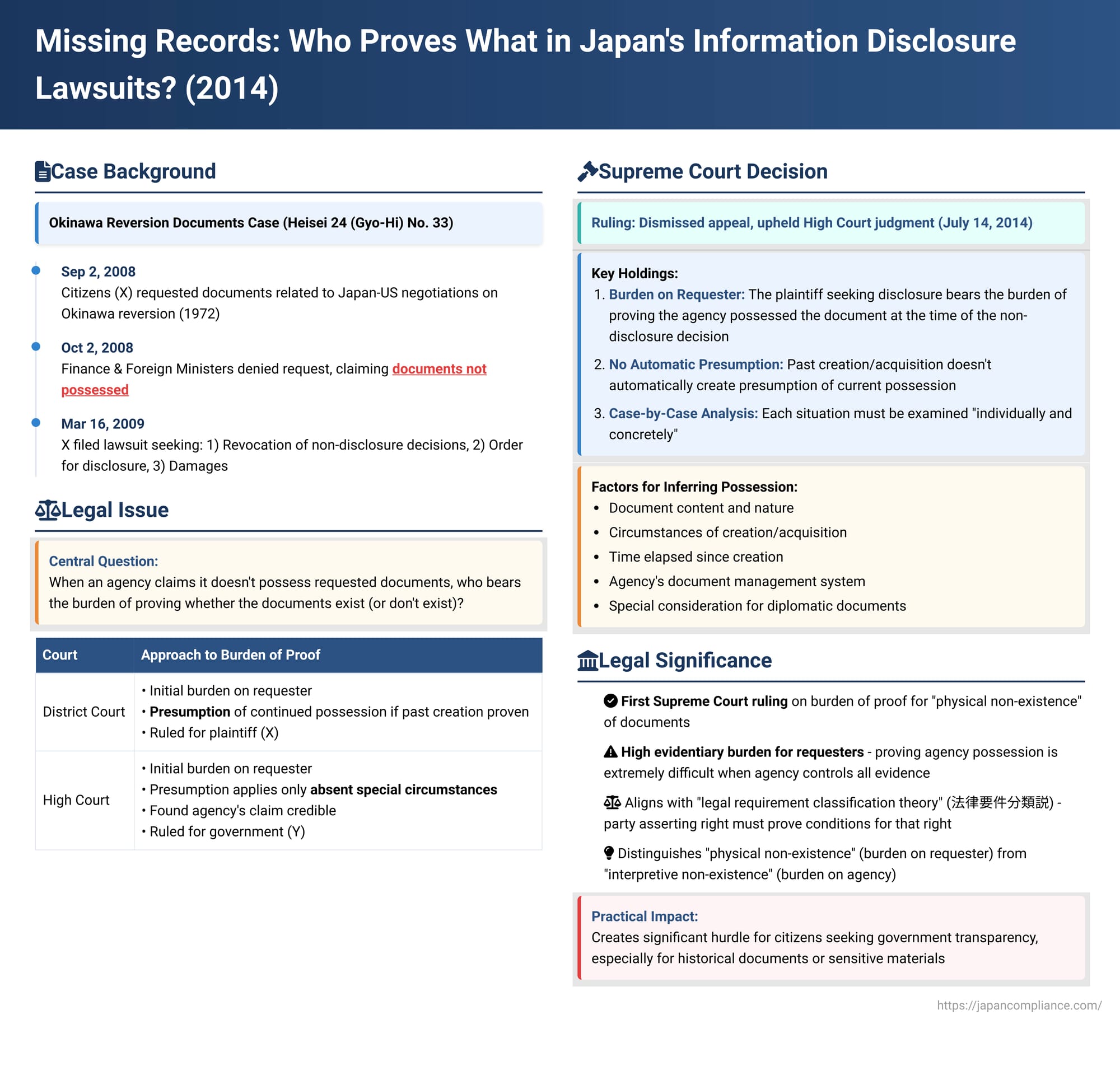

Missing Records: Who Proves What in Japan's Information Disclosure Lawsuits?

Judgment Date: July 14, 2014

Case Number: Heisei 24 (Gyo-Hi) No. 33 – Claim for Revocation of Non-Disclosure Decision of Documents, etc.

Japan's Information Disclosure Act grants citizens the right to access documents held by administrative organs, a vital tool for transparency and accountability. However, a common hurdle arises when an agency responds to a request by stating it simply does not possess the requested documents. This leads to a critical legal question: in a subsequent lawsuit challenging such a non-disclosure decision, who bears the burden of proving whether the agency actually holds (or does not hold) the documents in question? A 2014 Supreme Court decision provided a significant, and for requesters, challenging answer.

The Okinawa Reversion Documents Case

The case involved a group of citizens (X and others) who, on September 2, 2008, filed information disclosure requests with Japan's Finance Minister and Foreign Minister. They sought access to specific government documents related to the historical negotiations between Japan and the United States concerning the financial burdens associated with the 1972 reversion of the Ryukyu Islands (including Okinawa) and the Daito Islands to Japanese administration.

On October 2, 2008, both Ministers issued non-disclosure decisions. Their common reason was that their respective ministries did not possess the requested documents.

Dissatisfied, X and others filed a lawsuit against the State (Y) on March 16, 2009, seeking:

- Revocation of the non-disclosure decisions.

- A court order compelling the disclosure of the documents.

- Damages for emotional distress caused by the non-disclosure.

Lower Courts' Approaches to Proof and Presumption

The lower courts grappled with how to handle the burden of proof regarding the agencies' possession of the documents:

- The Tokyo District Court (first instance) ruled that the plaintiffs (X and others) had the burden to prove two things:

- That at some point in the past, agency officials had, in the course of their duties, created or obtained the administrative documents in question, and the agency had thereby come to possess them.

- That this state of possession had continued thereafter.

However, the District Court also held that if the plaintiffs successfully proved the first point (initial creation/acquisition), then, considering that administrative documents are normally managed systematically within an agency, the second point (continued possession) would be factually presumed. The burden would then shift to the agency (Y) to prove that the documents were subsequently disposed of, transferred, or otherwise ceased to be in its possession before the time of the non-disclosure decision. The District Court ultimately found the non-disclosure decisions in this case to be illegal.

- The Tokyo High Court (second instance) agreed that the plaintiffs bore the initial burden of proving both past creation/acquisition and continued possession. It also agreed that if past creation/acquisition was proven, continued possession at the time of the non-disclosure decision would be factually presumed, provided there were no special circumstances that would prevent such a presumption. However, the High Court added that if the agency presented counter-evidence suggesting such "special circumstances" and raised doubts about continued possession, this presumption would be broken. In this specific case, the High Court found there was reasonable doubt that these particular historical diplomatic documents had been under a standard, systematic management regime. It therefore concluded that the non-disclosure decisions were lawful, overturning the District Court.

X and others then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling (July 14, 2014): Plaintiff Bears the Burden of Proving Possession

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by X and others, thereby upholding the High Court's decision that the non-disclosure was lawful. The Supreme Court laid out its reasoning on the burden of proof and the inference of possession:

Burden of Proof for Agency Possession

- Legal Basis: The Information Disclosure Act defines an "administrative document" (the target of disclosure requests) as a document created or obtained by agency officials, used organizationally by those officials, and "held" (保有している - hoyū shiteiru) by the administrative agency (Article 2, Paragraph 2). The right to request disclosure is specifically for documents "held" by the agency (Article 3).

- Possession as a Requirement: The Court stated that the agency's possession of the requested administrative document is a constituent requirement for the right to request disclosure to be established (kaiji seikyūken no seiritsu yōken to sareteiru).

- Plaintiff's Burden: Therefore, in a lawsuit seeking to revoke a non-disclosure decision that was based on the agency's claim of not possessing the document, the person seeking revocation (the plaintiff) bears the burden of pleading and proving that the administrative agency possessed the administrative document at the time of the non-disclosure decision. Legal commentary notes that this allocation aligns with the "legal requirement classification theory" (hōritsu yōken bunrui setsu), a common approach to assigning the burden of proof where the party whose claim depends on a particular legal requirement being met must prove that requirement.

Inferring Possession at the Time of the Non-Disclosure Decision

The Supreme Court then addressed how a plaintiff might meet this burden if direct proof of current possession is unavailable:

- No Automatic Presumption: If a plaintiff proves that agency officials created or obtained the administrative document at some point in the past, but cannot directly prove its possession at the time of the non-disclosure decision, whether such current possession can be inferred is not automatic. It must be examined individually and concretely in each case. This differs from the more default-presumption approach of the District Court.

- Factors for Consideration: The possibility of inferring current possession depends on various factors, including:

- The content and nature of the administrative document.

- The circumstances surrounding its creation or acquisition.

- The length of time that has passed between its creation/acquisition and the non-disclosure decision.

- The agency's system and actual situation of its storage and management of such documents.

- Special Consideration for Certain Document Types: The Court specifically noted that for administrative documents created during diplomatic negotiations with other countries (such as those potentially falling under disclosure exemptions in Article 5, Item 3 of the Act – e.g., information that could harm relations of trust or be disadvantageous in negotiations), it must be considered that their storage systems and situations might differ from the norm. This implies that inferring continued possession of such sensitive documents might be more difficult.

Application to the Okinawa Reversion Documents

Applying these principles to the specific documents requested by X and others:

- The Supreme Court considered the apparent content and nature of these documents related to historical Japan-U.S. negotiations, the circumstances of their creation, and the many years that had passed until the 2008 non-disclosure decisions.

- It also took into account the results of investigations conducted by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Finance (including the pre-reform Ministry of Finance) concerning their document storage and management systems and practices.

- Based on all these legally established circumstances, the Court concluded that even if it were assumed that "these documents" were created by officials of these ministries during "this negotiation," it was insufficient to infer that the ministries still possessed them at the time of "these non-disclosure decisions." No other circumstances were found to support such an inference.

Therefore, X and others had not met their burden of proving that the agencies possessed the documents at the time of refusal, and the non-disclosure decisions were upheld.

Significance of the Ruling

This 2014 Supreme Court decision is highly significant for information disclosure litigation in Japan:

- Clarifies Burden of Proof: It definitively places the burden on the requester (plaintiff) to prove that the agency possessed the requested document at the time of its non-disclosure decision, when the agency claims non-possession. This was the first Supreme Court ruling to clarify the burden of proof for "physical non-existence" of documents.

- Rejects Automatic Presumption of Continued Possession: The ruling moves away from any simple or automatic presumption that if a document once existed within an agency, it is presumed to continue to be held by that agency.

- Emphasizes Case-Specific, Concrete Inquiry: The Court mandates a detailed, case-by-case examination of multiple factors before current possession can be inferred from past creation or acquisition.

- Highlights Challenges with Sensitive/Old Documents: It acknowledges that for certain types of documents, particularly older ones or those involving sensitive matters like diplomatic negotiations, standard document management practices might not have been followed, or special handling might have occurred, making an inference of current possession more difficult.

Challenges for Requesters and Broader Context

This ruling undoubtedly presents significant challenges for citizens seeking information:

- Proving that an agency currently possesses a specific document, especially when the agency denies having it and controls all information about its own record-keeping systems, can be an extremely difficult evidentiary hurdle for an external requester.

- Critics might argue that such a high burden could allow agencies to evade disclosure obligations by simply claiming non-possession, potentially undermining the effectiveness of the Information Disclosure Act.

It is important to consider this ruling in context:

- Physical vs. Interpretive Non-Existence: This case concerned "physical non-existence" (the agency claims the document is nowhere to be found). Legal commentary distinguishes this from "interpretive non-existence," where a document physically exists, but the agency argues it doesn't meet the Act's definition of an "administrative document" (e.g., it's a draft, a personal memo not used organizationally). In cases of interpretive non-existence, the burden is generally understood to be on the agency to prove why the existing document is not subject to disclosure.

- Impact of the Public Records and Archives Management Act: This case involved documents created long before the full implementation of Japan's Public Records and Archives Management Act (公文書管理法 - Kōbunsho Kanri Hō). For documents created and managed under this more recent and stricter legal framework for record-keeping, the factual basis for inferring continued possession might be stronger in future cases.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 2014 decision on the burden of proof in information disclosure cases where an agency claims non-possession sets a demanding standard for requesters. While based on a legal interpretation that places the onus of proving the conditions for a right (including agency possession) on the one asserting that right, the judgment highlights the inherent informational asymmetry and practical difficulties citizens face. It underscores the ongoing tension between the public's right to know and the challenges of verifying an agency's claims about the records it holds, particularly for historical or potentially sensitive materials.