Missing Employee, Effective Dismissal? Japan's Supreme Court on Notifying Absent Public Servants

A First Petty Bench Ruling from July 15, 1999

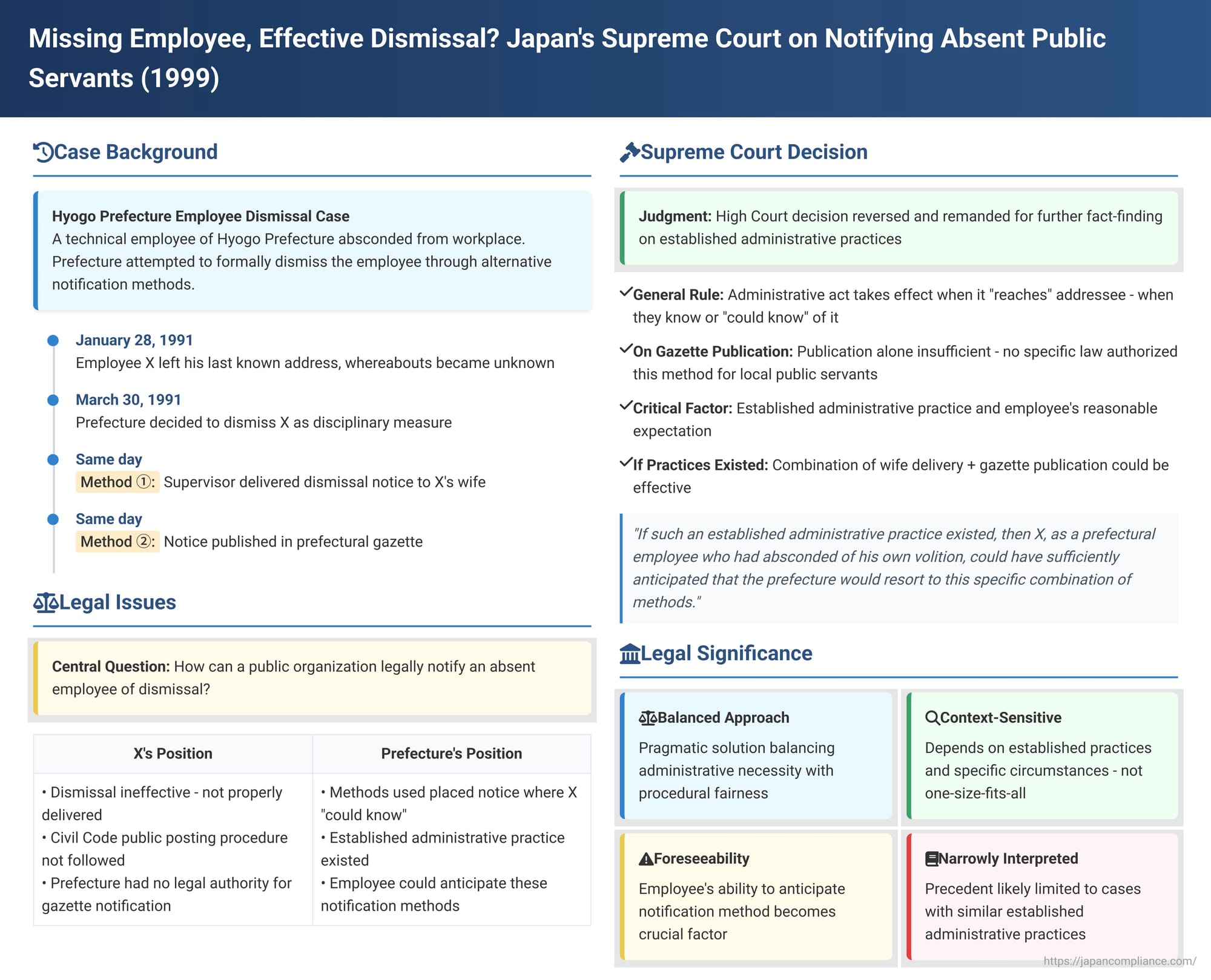

Taking official administrative action against an individual, such as a disciplinary dismissal from employment, typically requires that the person be properly notified for the action to take legal effect. But what happens when the individual's whereabouts are unknown? This complex issue was at the heart of a Japanese Supreme Court decision by its First Petty Bench on July 15, 1999 (Heisei 9 (O) No. 367). The case involved a prefectural public servant who had absconded, and it explored whether the methods used by the prefecture to communicate his dismissal were sufficient for that dismissal to become legally effective.

The Case of X: Abscondment and Dismissal

The plaintiff, X (represented in court by a court-appointed administrator of his property due to his absence), was a technical employee of Y, Hyogo Prefecture, working at one of its civil engineering offices. On January 28, 1991, X left his last known address and subsequently, his location and whether he was even alive became unknown.

Following X's unauthorized and continued absence, the Governor of Hyogo Prefecture decided on March 30, 1991, to dismiss X from his position as a disciplinary measure. An official notice of personnel action (人事発令通知書 - jinji hatsurei tsūchisho) and a written explanation of the reasons for the dismissal (処分説明書 - shobun setsumeisho) were prepared on that date.

The prefecture then took two steps to communicate this decision:

- Delivery to Wife (Method ①): On March 30, 1991, X's supervisor visited X's last known address. The supervisor read aloud the contents of the personnel action notice and the explanation of reasons to X's wife, A, and then delivered these documents to her.

- Publication in Prefectural Gazette (Method ②): Also on March 30, 1991, Y Prefecture published the content of the personnel action notice in the official prefectural gazette (公報 - kōhō). Subsequently, on April 6, 1991, a copy of this gazette was mailed to X's last known address.

The Legal Framework: Delivery of Dismissal Orders

The procedure for disciplinary actions against local public servants is generally governed by the Local Public Service Act (地方公務員法 - Chihō Kōmuin Hō), which in turn allows for details to be stipulated by local ordinances.

- Hyogo Prefecture had an "Ordinance concerning Procedures and Effects of Disciplinary Dispositions of Employees." Article 2 of this ordinance required that a disciplinary dismissal "must be effected by delivering to the said employee a written document stating the reasons therefor".

- Critically, this prefectural ordinance did not contain any specific provisions detailing how to proceed with notification if the employee's whereabouts were unknown and direct delivery of the written document was impossible. This contrasted with the rules for national public servants, where the National Personnel Authority regulations explicitly allowed for publication in the national Official Gazette (Kanpō) to substitute for direct delivery in cases of unknown whereabouts.

- While Japan's Civil Code (then Article 97-2, now Article 98) provided a formal procedure for "notification by public posting" (公示送達 - kōji sōtatsu) for declarations of intent when a recipient's location is unknown, the prefecture had not formally invoked this specific Civil Code procedure.

The Dispute: Did the Dismissal Legally Take Effect?

X (through his property administrator) filed a lawsuit, contending that the disciplinary dismissal had not legally taken effect. The argument was that the dismissal order had not been delivered directly to X as required, nor had it been served through any other legally appropriate method, such as the formal notification by public posting stipulated in the Civil Code.

The lower courts came to different conclusions:

- The Kobe District Court (first instance) held that even if formal Civil Code public posting wasn't used, a disposition could take effect if an "appropriate method by which the person subject to the disposition could know of the disposition" was employed. It found that the methods used by Hyogo Prefecture (delivery to X's wife and publication in the prefectural gazette) were appropriate in this context and, therefore, the dismissal was valid and effective.

- The Osaka High Court (second instance) overturned this. It reasoned that because X had absconded (a more permanent state than a temporary outing), delivery to his wife did not mean the dismissal notice was placed in a state where X himself could know of it. Regarding publication in the prefectural gazette, the High Court stated that without a specific law or ordinance authorizing this method for serving notice on an absent employee, and without invoking the Civil Code's formal public posting procedure, the prefecture could not unilaterally declare its own gazette publication to be effective service. The High Court opined that the "legitimacy of notification by public posting lies in the fact that its existence is generally announced to the other party and the public by law". Thus, it concluded the dismissal had not taken legal effect. Hyogo Prefecture (Y) appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision of July 15, 1999

The Supreme Court overturned the Osaka High Court's decision and remanded the case for further factual findings. The Court's reasoning focused on the concept of foreseeability based on established administrative practice.

Core Reasoning: Foreseeability Based on Established Practice:

- General Principle of Effectuation: The Court began by reiterating the general legal principle that an administrative act, such as a dismissal, takes effect when the declaration of intent "reaches" the addressee. This means either when the addressee actually knows of it, or when it is placed in a state where they "could know of it" (了知し得べき状態 - ryōchi shiubeki jōtai), unless special legal provisions dictate otherwise. This principle had been established in prior Supreme Court cases.

- Prefectural Gazette Publication Alone Insufficient: The Court agreed with the High Court on one point: mere publication of the dismissal notice in the Hyogo prefectural gazette, by itself, could not immediately cause the dismissal to take legal effect. This was because there was no specific law or Hyogo prefectural ordinance that explicitly authorized this method as a substitute for direct delivery to an absent local public servant, unlike the clear rules for national public servants.

- The Crucial Factor – Established Prefectural Practice and Employee's Expectation: The Supreme Court then introduced a critical consideration that the High Court had apparently overlooked. The Prefecture (Y) had argued that it had a long-standing, consistent administrative practice for handling disciplinary dismissals of employees whose whereabouts were unknown. This practice, allegedly based on a 1955 response from a senior official at the then-Autonomy Agency (a national body overseeing local government affairs) to an inquiry from another prefecture, involved:

- Delivering the official order (personnel action notice) and the written explanation of reasons to the cohabiting family members of the absent employee.

- Concurrently, publicizing the content of the disposition in the prefectural official gazette and sometimes in newspapers.

The Supreme Court found that the case record contained indications that such a practice might indeed have been followed in Hyogo Prefecture.

The Court reasoned that if such an established administrative practice existed, then X, as a Hyogo prefectural employee who had "absconded of his own volition and continued in unauthorized absence," could have "sufficiently anticipated" (十分に了知し得た - jūbun ni ryōchi shieta) that the prefecture would resort to this specific combination of methods to effect his disciplinary dismissal.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that if such a practice was indeed established and X, given his circumstances and status as a prefectural employee, could reasonably have foreseen this method of notification, then the disciplinary dismissal—effected approximately two months after he absconded, using these combined methods—should be deemed to have taken legal effect.

Remand for Factual Inquiry:

Because the Osaka High Court had not adequately examined the existence of this alleged established administrative practice in Hyogo Prefecture, nor had it considered whether X could have reasonably foreseen this method of notification, the Supreme Court found that the High Court's judgment was based on an error in the interpretation and application of the law. The case was therefore remanded to the Osaka High Court for further proceedings to determine these factual and related legal points.

"Coming into Effect" (発効 - Hakkō) of Administrative Acts

This case revolves around the legal concept of when an administrative act "comes into effect" or becomes legally operative.

- The general rule in Japanese administrative law is that an act takes effect when its content "reaches" the addressee. This doesn't always mean actual, physical receipt or reading by the addressee; it is often sufficient if the information is placed in a condition where the addressee could reasonably be expected to become aware of it (了知し得べき状態 - ryōchi shiubeki jōtai).

- This case highlights the difficulty in applying this principle when the addressee has made themselves unreachable. The Supreme Court looked for a basis upon which X could have known how the prefecture would proceed.

Serving Notice When Whereabouts are Unknown: A Spectrum of Legal Views

The question of how to validly serve notice on an individual whose whereabouts are unknown, especially when no specific statute dictates the method, has been a subject of varied legal theories in Japan. The legal commentary accompanying the case material outlines several approaches:

- Some argue that any method that makes knowledge possible for the addressee, such as public posting, should suffice (Theory ①).

- Others reject public posting by an administrative agency without explicit statutory authority, citing the fictional nature of such service and potential prejudice to the individual (Theory ②). This view might also reject applying the Civil Code's general provisions for public posting of private declarations of intent.

- A third view (taken by the Osaka High Court in this case) might reject unilateral public posting by an agency but permit the use of the Civil Code's formal public posting procedures (Theory ③).

- Yet another approach suggests balancing administrative necessity against the individual's potential prejudice (e.g., loss of appeal rights) on a case-by-case basis, potentially allowing agency-initiated public posting (e.g., on a bulletin board) if the administrative need is compelling (Theory ④).

- A fifth view, which this Supreme Court judgment appears to align with, suggests that while the Civil Code's public posting provisions might be referred to, no single method is universally applicable or exclusively permissible. The key is to determine, based on the specific circumstances of each case, whether the method used can legally be deemed to have "reached" the addressee (Theory ⑤).

The Supreme Court in this 1999 decision did not lay down a general, universally applicable rule for service on absent local public servants. It specifically refrained from stating that publication in the prefectural gazette alone would be sufficient. Instead, it tied the potential effectiveness of the notification to a combination of (a) delivery to cohabiting family, (b) publication in the prefectural gazette, (c) the existence of an established, consistent administrative practice of using these combined methods, and, crucially, (d) the absconding employee's "sufficient ability to foresee" this specific method being used in their case.

Significance of the Ruling

This Supreme Court judgment is significant for its nuanced approach to a difficult procedural problem:

- It does not create a blanket approval for prefectures to use their own gazettes as a general means of service by public posting for absent employees in the absence of specific legal authorization.

- However, it opens the door for such methods (especially when combined with other efforts like notification to family) to be considered effective if a consistent, known administrative practice exists, and if the employee, due to their status and actions, could reasonably have anticipated that such a practice would be applied to them. The employee's own conduct (absconding) and their status as a public servant (who might be expected to be aware of their employer's established procedures) were important contextual factors.

- The ruling emphasizes a fact-intensive inquiry. The precedential value for other cases of "service on absentees" where such specific, foreseeable local practices might not exist is, as the commentary suggests, likely to be "interpreted narrowly". Nevertheless, it does provide a general judicial approach: to consider all specific circumstances when judging whether notice can be deemed to have effectively "reached" an absent individual.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1999 decision in the case of the absent Hyogo prefectural employee offers a pragmatic, albeit context-dependent, solution to the challenge of effectuating a disciplinary dismissal when the employee is missing. It balances the need for administrative bodies to take necessary personnel actions with the requirement that such actions be properly communicated to be legally effective. The judgment underscores that while direct, personal notification is the ideal, and while legally prescribed methods for dealing with absentees (where they exist) must be followed, a combination of other notification efforts, if part of a well-established and reasonably foreseeable administrative practice, might suffice to bring an administrative act into legal effect. The ruling implicitly encourages public employers to have clear, consistent, and ideally legally grounded procedures for such eventualities.