Misled into a Bad Deal? Japanese Supreme Court on Pre-Contractual Duty to Explain and Its Consequences

Date of Judgment: April 22, 2011

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Case No. 1940 (Ju) of 2008 (Damages Claim Case)

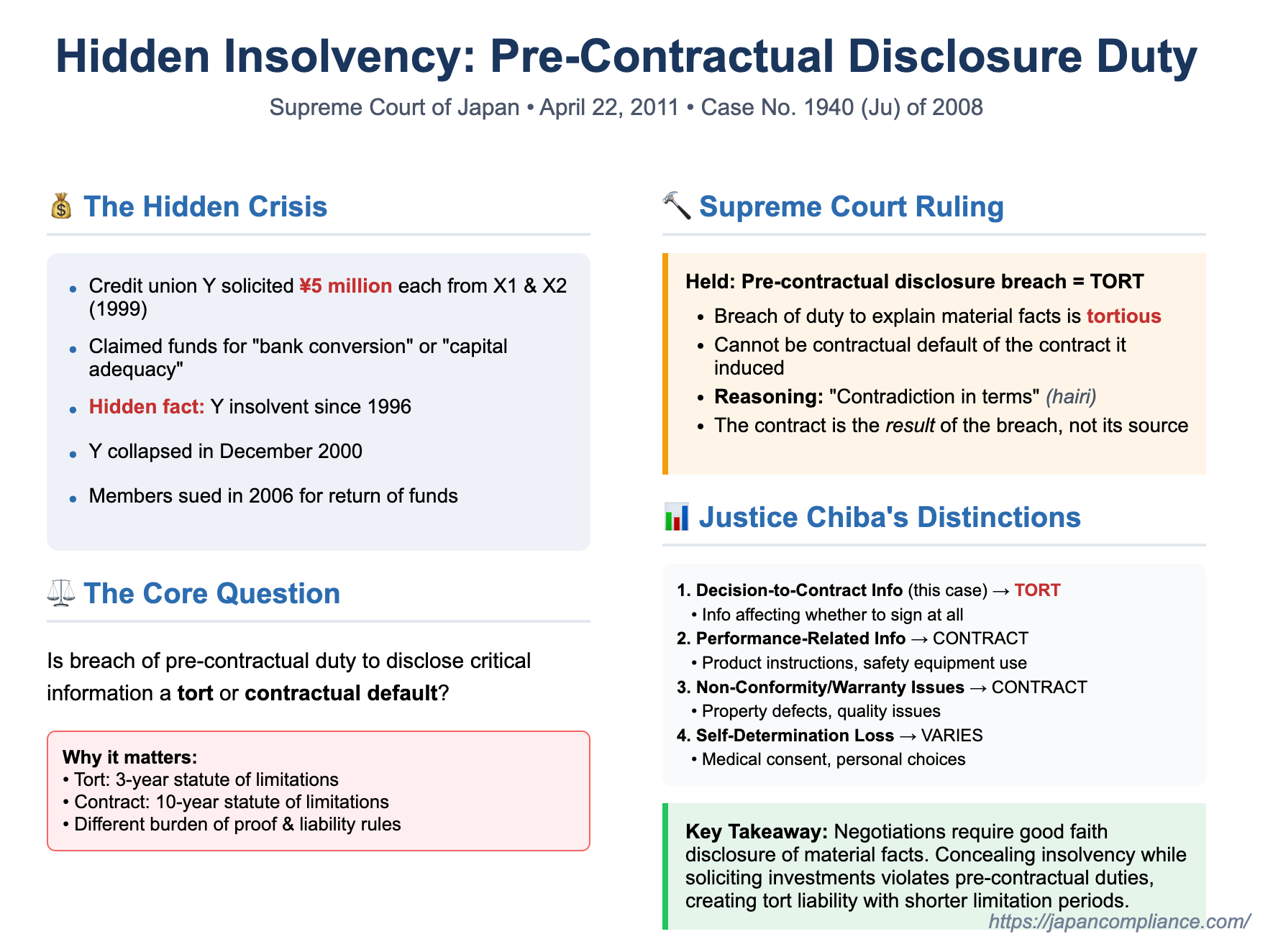

The process of entering into a contract is often preceded by negotiations and exchanges of information. Parties rely on the information provided by each other to make informed decisions. But what happens if one party fails to disclose critical, negative facts about itself or the subject matter of the contract, leading the other party to enter into a deal they would have otherwise avoided? If the misled party suffers a loss as a result, what is the legal nature of their claim for damages? Is it a breach of the contract that was ultimately formed, or is it a separate wrong, a tort, committed during the pre-contractual phase? This crucial distinction, particularly relevant for issues like the statute of limitations, was addressed by the Supreme Court of Japan in a significant decision on April 22, 2011.

The Failing Credit Union and Its Members: Facts of the Case

The defendants (and appellants in the Supreme Court) included Y, a credit cooperative. In March 1999, Y solicited its members, X1 and X2 (the plaintiffs and respondents), to make additional capital contributions to the cooperative. Y's representatives told X1 and X2 that these additional funds were necessary either for Y's planned conversion into an ordinary bank or to improve its capital adequacy ratio. Persuaded by these representations, X1 and X2 each contributed 5 million yen to Y.

However, Y's financial situation was far more precarious than disclosed. As far back as 1996, an inspection by regulatory authorities had revealed that Y was effectively insolvent, with a negative capital adequacy ratio. Despite being urged by the authorities to take urgent corrective measures, Y had failed to resolve its deep-seated financial problems. Ultimately, on December 16, 2000, the Financial Reconstruction Commission of Japan issued a formal disposition against Y, and its business operations collapsed.

Following Y's collapse, X1 and X2 realized they had been induced to make their contributions based on incomplete or misleading information. They argued that at the time Y solicited their funds, Y's management was aware, or should have been aware, of a very real and imminent danger that Y would be declared bankrupt by the regulatory authorities. In such an event, the invested capital contributions made by members like X1 and X2 would likely become irrecoverable. X1 and X2 contended that Y had a duty to explain this critical risk to them before soliciting their contributions but had failed to do so. They further alleged that Y had, in fact, actively deceived them by misrepresenting its financial health as sound.

X1 and X2 filed a lawsuit against Y on September 8, 2006, seeking the return of their 5 million yen contributions each, plus damages for delay. Their primary legal grounds were: (i) tort (unlawful act causing harm), or (ii) unjust enrichment resulting from either fraudulent inducement or fundamental mistake concerning the contract (the mistake claim was added during the second instance appeal). As an alternative (subsidiary) claim, they argued for damages based on (iii) a breach of contractual duty (default) under the capital contribution agreements themselves. The timing of their lawsuit was influenced by a successful outcome in a similar prior lawsuit brought by other contributors against Y.

The Osaka District Court (first instance) and the Osaka High Court (second instance) both found that Y had indeed breached its duty of explanation to X1 and X2. However, they dismissed the primary claims based on tort and unjust enrichment (the right to cancel for fraud was deemed extinguished by the statute of limitations, and the mistake claim was disallowed on the grounds that a capital contribution to a cooperative is a "collective act" not easily undone by individual mistake). Instead, the lower courts partially upheld the alternative claim (iii), finding Y liable for a breach of contractual duty. The High Court, in its reasoning, stated that for culpa in contrahendo (fault in the pre-contractual stage), liability based on the principle of good faith governing contract law should be considered a form of contractual default liability, potentially imposing heavier responsibilities on the defaulting party concerning matters like burden of proof and vicarious liability compared to general tort law. Y appealed this finding of contractual liability to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Question: Contractual Breach or Tort for Pre-Contractual Misinformation?

The pivotal issue before the Supreme Court was the correct legal characterization of liability arising from a breach of a duty to provide critical information before a contract is signed. If such a breach induces the other party to enter into a detrimental contract, is the resulting claim for damages based on a breach of the contract that was eventually formed, or is it based on a tort committed during the negotiation phase? This distinction was critical, particularly for determining the applicable statute of limitations, as tort claims often had a shorter limitation period under the old Civil Code than contractual claims.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Pre-Contractual Breach Sounds in Tort, Not Contract

The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's judgment on the point of contractual liability. The Supreme Court held that a breach of a pre-contractual duty of explanation gives rise to tort liability, not liability for contractual default.

The Core Principle:

The Court laid down the following principle: "If one party to a contract, prior to the conclusion of said contract, violates a duty of explanation under the principle of good faith and fails to provide the other party with information that should influence the decision regarding whether or not to conclude said contract, then the first party may bear liability for damages under tort law for losses suffered by the other party as a result of concluding said contract. However, it should be said that they do not bear liability for damages due to non-performance of an obligation under the said (subsequently concluded) contract."

Reasoning ("Contradiction in Terms" - 背理 - haeri):

The Court's rationale for this conclusion was based on a perceived logical inconsistency: "Because, as stated above, when one party violates a duty of explanation under the principle of good faith, and as a result, the other party concludes a contract they would not have concluded had things been otherwise, thereby suffering loss, the subsequently concluded contract is positioned as a result brought about by the violation of the said duty of explanation. To say that the said duty of explanation is an obligation arising based on the said (subsequently concluded) contract—regardless of whether one calls it a primary contractual obligation or an ancillary duty—must be described as a type of contradiction in terms." The Court further added that even if the principle of good faith governs the legal relationship between parties during the contract preparation stage and gives rise to duties, it does not automatically follow that such duties become obligations under the contract that is subsequently concluded.

Consequence for Statute of Limitations:

Because the liability is characterized as tortious, the statute of limitations applicable to tort claims would apply. Under the old Civil Code (Article 724, first part), this was generally three years from the time the victim became aware of the damage and the identity of the perpetrator. The Supreme Court briefly noted that, considering the purpose of the tort statute of limitations and the way its starting point is defined, this application should not unduly hinder the relief of victims' rights.

Ultimately, based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court quashed the part of the High Court's judgment that had found Y liable for contractual default and, proceeding to rule on the merits of that specific claim itself, dismissed X1 and X2's claims based on contractual default. (While the provided text focuses on this point, the overall context implies that because the contractual claim failed and the tort claims were likely time-barred or otherwise dismissed by the lower courts, this determination was fatal to the plaintiffs' success on the grounds appealed).

Justice Chiba's Concurring Clarification

Justice Chiba Katsumi, in a supplementary concurring opinion, elaborated on the distinction between different types of pre-contractual duties.

- He agreed with the majority that a breach of a pre-contractual duty of explanation, of the type at issue in this case (i.e., concerning information critical to the decision whether to enter into the contract at all), gives rise to tort liability, not contractual default liability. Such duties, he reasoned, arise from the very act of entering into negotiations and are based on good faith governing that preparatory phase, not from the contract that might later be formed.

- However, Justice Chiba distinguished these from other types of duties that might also arise or be discussed in a pre-contractual context but could properly be seen as ancillary duties of the concluded contract itself. He gave examples such as the duty of an electrical appliance seller to give proper instructions on product use to a customer, or a real estate agent's duty to explain the operation of safety equipment in a condominium to a buyer. Such duties, even if the explanation occurs before contract signing, are fundamentally linked to the proper performance and intended purpose of the contract being entered into. Their breach could therefore be treated as a contractual default.

- The duty in the present case—to disclose the credit union's dire financial health before soliciting further capital contributions—was, in Justice Chiba's view, squarely of the first type: it related solely to the members' decision-making process of whether to enter into the contribution agreement, and its relevance was confined to the pre-contractual stage. It was not an ongoing ancillary duty of the contribution agreement once formed.

Unpacking the Duty of Explanation in Contract Negotiations

This Supreme Court decision is a significant marker in the Japanese law concerning "culpa in contrahendo" or pre-contractual liability. It specifically addresses liability for failure to disclose critical information that leads to the formation of a contract.

- Good Faith as the Basis: The underlying principle is that parties entering into negotiations owe each other duties derived from good faith. This can include a positive duty to provide information under certain circumstances.

- When is this Duty Breached? A breach typically occurs when there is a failure to disclose information that is material to the other party's decision to enter into the contract, especially when:

- There is a significant asymmetry of information, knowledge, or experience between the parties (e.g., a financial institution dealing with an ordinary member). This aligns with the protective aims of laws like the Consumer Contract Act.

- The party possessing the information is a professional or expert in the relevant field, implying a heightened responsibility. Many specific laws (e.g., Financial Instruments and Exchange Act, Insurance Business Act) impose statutory explanation duties on professionals, and breaches of these can inform the good faith analysis.

- The concealed information concerns severe negative facts that, if known, would almost certainly lead the other party to refuse the contract (as in this case, where Y was effectively insolvent).

- If the failure to explain relates to matters that could endanger fundamental "integrity interests" like life or physical health (or the economic basis for survival), the duty may be elevated from mere information provision to include warnings or advice.

- Categorizing Pre-Contractual Explanation Duties: The legal commentary around this decision, including Justice Chiba's opinion, helps to categorize different types of pre-contractual explanation duties and their potential legal consequences:

- Decision-to-Contract Explanation Duty (as in this case): Information critical for deciding whether to enter the contract. A breach that induces an unwanted contract is deemed a tort, with damages typically aimed at restoring the party to their pre-contract position (reliance damages).

- Performance-Related Explanation Duty: Information necessary for the proper performance, use, or enjoyment of the subject matter of the contract (e.g., instructions for a product). A breach here is more likely to be treated as a contractual default (breach of an ancillary duty of the concluded contract).

- Duties Overlapping with Non-Conformity/Warranty: For example, the duty of a seller to disclose significant "psychological defects" in a property (like a previous suicide on the premises). Under current law, this might be handled under rules for non-conformity of goods/property. Damages here are not typically aimed at unwinding the contract as in the first category.

- "Loss of Chance" for Self-Determination: This often arises in non-financial contexts, such as medical informed consent. Failure to provide adequate information for a crucial personal decision may lead to damages for emotional harm due to the loss of the opportunity for self-determination, rather than purely financial restitution.

In the specific circumstances of the credit union Y and its members X1 and X2, the information about Y's insolvency was clearly critical. Y possessed this information, while its members did not and could not easily discover it. Y's act of concealing this dire situation while actively soliciting further investment from its members constituted a clear breach of the duty of explanation required by good faith.

Significance of the Ruling

The Supreme Court's 2011 decision carries several important implications:

- Clarification of Legal Nature: It provides a clear pronouncement from Japan's highest court that a breach of the pre-contractual duty to explain material facts that influence the very decision to enter into a contract constitutes a tort, not a breach of the subsequently formed contract.

- Statute of Limitations: This characterization directly impacts the applicable statute of limitations. Under the Civil Code provisions in effect at the time of the underlying events and the lawsuit, tort claims generally had a shorter prescription period (three years from knowledge of harm and perpetrator) than contractual claims (ten years). This decision therefore had practical consequences for the timeliness of claims like those brought by X1 and X2. (Note: The 2017 Civil Code revisions have since modified and, in some respects, harmonized limitation periods, though differences still exist).

- Reinforcement of Good Faith in Negotiations: The ruling underscores the importance of transparency and honesty in the lead-up to contractual agreements. It affirms that the negotiation phase is not without legal duties, and that misleading or failing to inform a counterparty about critical adverse facts can result in liability.

Concluding Thoughts

The 2011 Supreme Court decision draws a distinct line between duties that arise during the pre-contractual negotiation phase and duties that flow from an already concluded contract. For failures in disclosure that are so fundamental that they induce a party to enter into a contract they would otherwise have shunned, the legal remedy, according to this judgment, lies in the realm of tort law. This approach emphasizes the wrongfulness of inducing such a detrimental decision. While the specific impact of this ruling on statutes of limitation has been affected by subsequent general revisions to the Civil Code, its core message about the tortious nature of breaching a duty to explain critical pre-contractual information remains a significant element of Japanese contract and tort jurisprudence. It serves as a caution that the freedom to negotiate does not extend to the freedom to mislead.