Minority Shareholder Rights on Shifting Sands: Shareholding Thresholds and Inspector Appointments in Japan

Case: Appeal against a High Court decision annulling a first-instance decision to dismiss an application for the appointment of an inspector, concerning a petition for permission to appeal.

Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Decision of September 28, 2006

Case Number: (Kyo) No. 12 of 2006

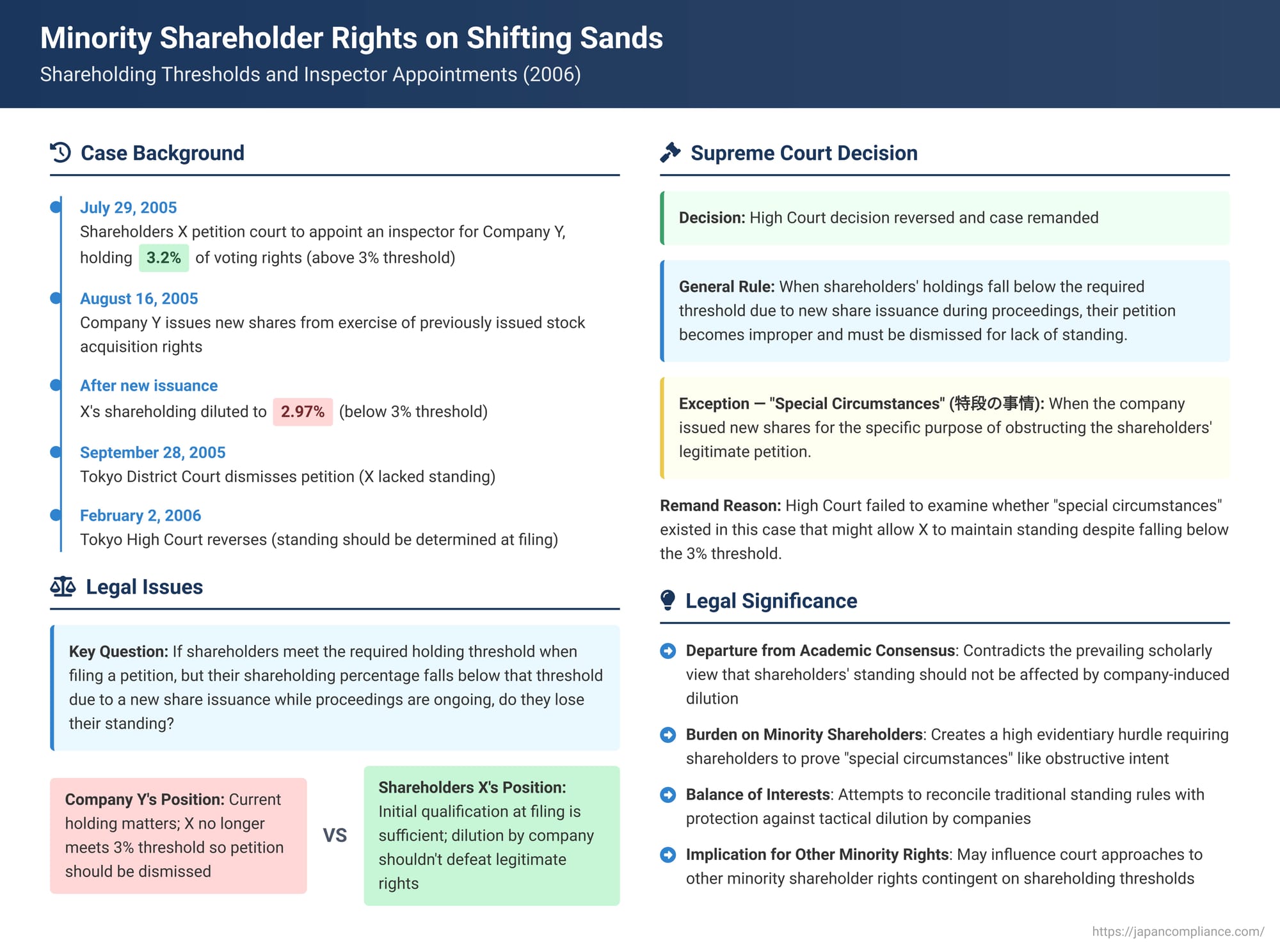

Minority shareholders in Japan possess several statutory rights designed to promote corporate transparency and accountability, one of which is the right to petition a court for the appointment of an inspector (検査役 - kensayaku) to investigate a company's business operations and financial condition if there are grounds to suspect serious wrongdoing. However, exercising this right often requires the petitioning shareholders to meet certain minimum shareholding thresholds. A critical question addressed by the Japanese Supreme Court on September 28, 2006, was whether shareholders who satisfy this threshold at the time they file their petition can lose their legal standing if their shareholding percentage subsequently drops below the required level due to new shares being issued by the company – an event often outside their direct control.

A Shareholder's Watchdog Role Put to the Test: Facts of the Case

The petitioners, X, were a group of shareholders in Company Y. On July 29, 2005, alleging accounting irregularities within Company Y, X filed a petition with the Tokyo District Court. They requested the court to appoint an inspector to investigate Company Y's business and financial affairs, a right provided under Article 294, Paragraph 1 of the then-applicable Commercial Code (a provision similar in substance to Article 358, Paragraph 1 of the current Companies Act).

At the time of filing this petition, X collectively held shares representing approximately 3.2% of the total voting rights in Company Y. This met the statutory requirement then in place, which mandated that such a petition be brought by shareholders holding at least 3% of the total voting rights.

However, a subsequent event altered this situation. On August 16, 2005, while X's petition was still pending before the court, Company Y issued new shares. This new share issuance was not a fresh offering initiated by the company at that moment, but rather resulted from the exercise of stock acquisition rights (新株引受権 - shinkabu hikiukeken) that were attached to corporate bonds Company Y had previously issued in the year 2000. As a consequence of these new shares being issued and the total number of voting shares increasing, X's collective voting power in Company Y was diluted to approximately 2.97%. This figure now fell slightly below the 3% threshold required by statute.

Company Y seized on this development, arguing that X no longer met the necessary shareholding requirement and, therefore, their petition for the appointment of an inspector should be dismissed for lack of standing.

The Lower Courts' Conflicting Views

The Tokyo District Court (court of first instance), in its decision on September 28, 2005, sided with Company Y. It dismissed X's petition, finding that because X's shareholding had fallen below the statutory 3% threshold, they no longer had the requisite standing to pursue the request for an inspector.

X appealed this decision. The Tokyo High Court, in its ruling on February 2, 2006, overturned the District Court's decision. The High Court reasoned that since X had undeniably met the statutory shareholding requirement at the time they filed the petition, their right to request the appointment of an inspector should not be extinguished simply because their shareholding percentage later decreased due to a new share issuance by the company. The High Court emphasized that this dilution was a result of circumstances largely outside X's control. It considered it would be unreasonable and contrary to the legislative intent behind minority shareholder protection rights if a company could effectively nullify such a petition by subsequently issuing new shares. The High Court therefore remanded the case back to the District Court for a substantive examination of X's request. It was this High Court decision that Company Y appealed to the Supreme Court, with the appeal being permitted.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: The "Special Circumstances" Caveat

The Supreme Court overturned the Tokyo High Court's decision and remanded the case back to the High Court for further proceedings.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: Maintaining the Threshold, Barring Abuse

The Supreme Court laid down the following principle:

Even if shareholders satisfy the statutory shareholding requirement (e.g., 3% of total voting rights) for petitioning a court to appoint a company inspector at the moment they file their application, if, during the course of the proceedings, the company issues new shares, and this issuance results in the petitioning shareholders' collective voting rights falling below the legally prescribed threshold, then, unless "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō) exist, the petition becomes improper due to the petitioners lacking the requisite standing (applicant's qualification - 申請人の適格 - shinseinin no tekkaku) and must be dismissed.

The Supreme Court identified one key example of such "special circumstances": if the company issued the new shares for the specific purpose of obstructing or thwarting the shareholders' legitimate petition for an inspector.

In this particular case, X's shareholding had fallen below the 3% threshold due to the new share issuance. Therefore, according to the general rule established by the Supreme Court, their petition would ordinarily become improper. However, the High Court had not examined whether "special circumstances," such as an obstructive intent on the part of Company Y in relation to the new share issuance, were present. Because the existence or non-existence of such special circumstances was critical to the final determination of X's standing, the Supreme Court remanded the case to the High Court for a specific examination of this point.

Analysis and Implications: A Shift in the Landscape for Minority Shareholder Rights

This 2006 Supreme Court decision has significant implications for the exercise of minority shareholder rights in Japan, particularly those rights contingent upon meeting specific shareholding thresholds.

- The Statutory Right to Request an Inspector:

The right of shareholders to request a court-appointed inspector (now under Article 358 of the Companies Act) is a crucial tool. It allows shareholders who suspect fraudulent acts (不正行為 - fusei kōi) or serious violations of laws or the company's articles of incorporation in the company's operations to seek an independent investigation. The shareholding thresholds (e.g., 3% of voting rights or 3% of total issued shares, though the Companies Act also allows these to be lowered by the articles of incorporation) are intended to act as a filter, preventing frivolous or abusive requests while empowering shareholders with a significant enough stake to raise legitimate concerns. - The Traditional View: Shareholding Requirement Must Persist Throughout:

Historically, Japanese case law, including a very old Daishin-in (pre-1947 Supreme Court) decision from 1921, had generally held that the statutory shareholding requirement for exercising such rights must be maintained by the shareholder throughout the entire legal process, up until the court's final decision. In the 1921 case, the shareholder had voluntarily sold some of their shares after filing the petition, causing their holding to drop below the threshold, and their petition was dismissed. Lower courts had, at times, extended this principle to situations where the loss of shareholding percentage was involuntary. - A Departure from the "Prevailing Scholarly View" for Company-Induced Dilution:

Before this 2006 Supreme Court ruling, a significant body of academic opinion (often referred to as the "prevailing view" or tsūsetsu) held that if petitioning shareholders met the threshold at the time of filing, their right should not be extinguished if their share percentage subsequently fell due to new shares being issued by the company itself. The rationale was that shareholders should not lose their legitimately acquired standing due to actions taken by the very entity they were seeking to investigate, especially if those actions were outside their control. The Tokyo High Court's decision in this case was largely in line with this prevailing scholarly view.

The Supreme Court's 2006 decision, however, effectively diverged from this particular scholarly consensus by stating that even in cases of dilution caused by the company's new share issuance, the shareholder's standing is generally lost. The only escape from this outcome is if the shareholders can demonstrate "special circumstances," primarily focusing on an improper, obstructive motive behind the company's share issuance. - Critiques and Concerns Regarding the Supreme Court's Stance:

The Supreme Court's decision has been met with considerable academic discussion and some criticism, particularly from those who favored the High Court's approach or the older prevailing scholarly view.- Critics argue that the primary purpose of the shareholding threshold is to prevent shareholders from abusing the right to request an inspector, not to provide a loophole for companies to thwart legitimate investigations by strategically issuing new shares.

- It is contended that once shareholders have established their standing by meeting the threshold at the time of filing and have presented a prima facie case for investigation, their right to pursue the matter should not be so easily defeated by subsequent actions of the company that are beyond their control.

- Furthermore, the burden of proving "special circumstances," such as the company's improper obstructive purpose, can be extremely difficult for minority shareholders, who typically lack access to the internal decision-making processes of the company's management regarding share issuances.

- Arguments in Support of the Supreme Court's Decision:

Conversely, some legal commentators find the Supreme Court's logic consistent with general principles of legal standing.- The shareholding requirement is a fundamental qualification for being an eligible applicant. As a general rule in legal proceedings, such qualifications or standing requirements must be met not only at the initiation of the action but also maintained throughout its duration.

- In situations like the present case, where new shares were issued due to the exercise of pre-existing stock acquisition rights, it could be argued that petitioning shareholders should have reasonably foreseen the possibility of such dilution.

- There isn't a universally established legal principle that, once standing is acquired, it can never be lost due to the actions of other parties, unless a statute specifically provides for such continuation (as the Companies Act does, for example, in certain derivative suit contexts like Articles 847-2 and 851, to prevent plaintiffs from losing standing if they cease to be shareholders after filing suit, under specific conditions).

- The "Special Circumstances" Exception – A Narrow Path?

The crucial lifeline offered by the Supreme Court is the "special circumstances" exception, with the primary example being a share issuance undertaken by the company with the "purpose of obstructing the shareholders' petition."- Establishing such an improper purpose presents a high evidentiary hurdle for shareholders.

- Some commentators suggest that if company insiders who are opposed to the inspection petition strategically exercise their own stock acquisition rights (or arrange for friendly parties to do so) with the clear aim of diluting the petitioners below the threshold, this might be construed as the company acting with an obstructive purpose, especially if collusion can be inferred.

- An alternative perspective debated by scholars is whether the burden of proof should shift. For instance, if a company issues new shares that it knows will dilute petitioning shareholders below the required threshold after a petition for an inspector has been filed, perhaps the company should then bear the burden of proving a legitimate and compelling business necessity for that share issuance at that particular time. If it cannot, "special circumstances" benefiting the shareholders might be more readily found.

- The possibility of shareholders seeking a court injunction to stop a new share issuance if its primary purpose is deemed to be the obstruction of legitimate shareholder rights (e.g., under Article 210, Item 2 of the Companies Act, concerning grossly unfair share issuances) also exists, but the success of such an injunction in the context of shares issued due to the exercise of pre-existing, validly granted stock acquisition rights would be highly uncertain.

- Potential Impact on Other Minority Shareholder Rights:

Commentary accompanying this decision has noted that its reasoning could potentially influence how Japanese courts approach the requirement of maintaining shareholding thresholds for the exercise of other minority shareholder rights (such as the right to demand the dismissal of a director or the right to inspect the company's accounting books). However, a direct, uncritical application of this specific ruling to all other minority rights is generally cautioned against. The nature of each individual right, the specific statutory language governing it, and the method of its exercise (e.g., whether it's an out-of-court demand versus a judicial proceeding, or a contentious versus a non-contentious matter) would need to be carefully considered.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision of September 28, 2006, establishes a stringent rule for minority shareholders in Japan seeking to utilize the important tool of a court-appointed company inspector. While the right is granted to those meeting an initial shareholding threshold, this standing is precarious. If the company subsequently issues new shares – even as a result of the exercise of previously granted stock acquisition rights – and the petitioning shareholders' stake is diluted below the statutory minimum, their petition will generally be dismissed for lack of standing. The only way to avoid this outcome is for the shareholders to prove "special circumstances," predominantly that the company's new share issuance was motivated by an improper purpose to obstruct their legitimate request for an investigation. This ruling underscores the challenges minority shareholders can face in maintaining their leverage throughout protracted legal battles, particularly when corporate actions can alter shareholding percentages. It places a considerable evidentiary burden on shareholders seeking to invoke the "special circumstances" exception.