Mind the Gap: Navigating Wage Disparity Between Fixed-Term and Indefinite-Term Employees in Japan

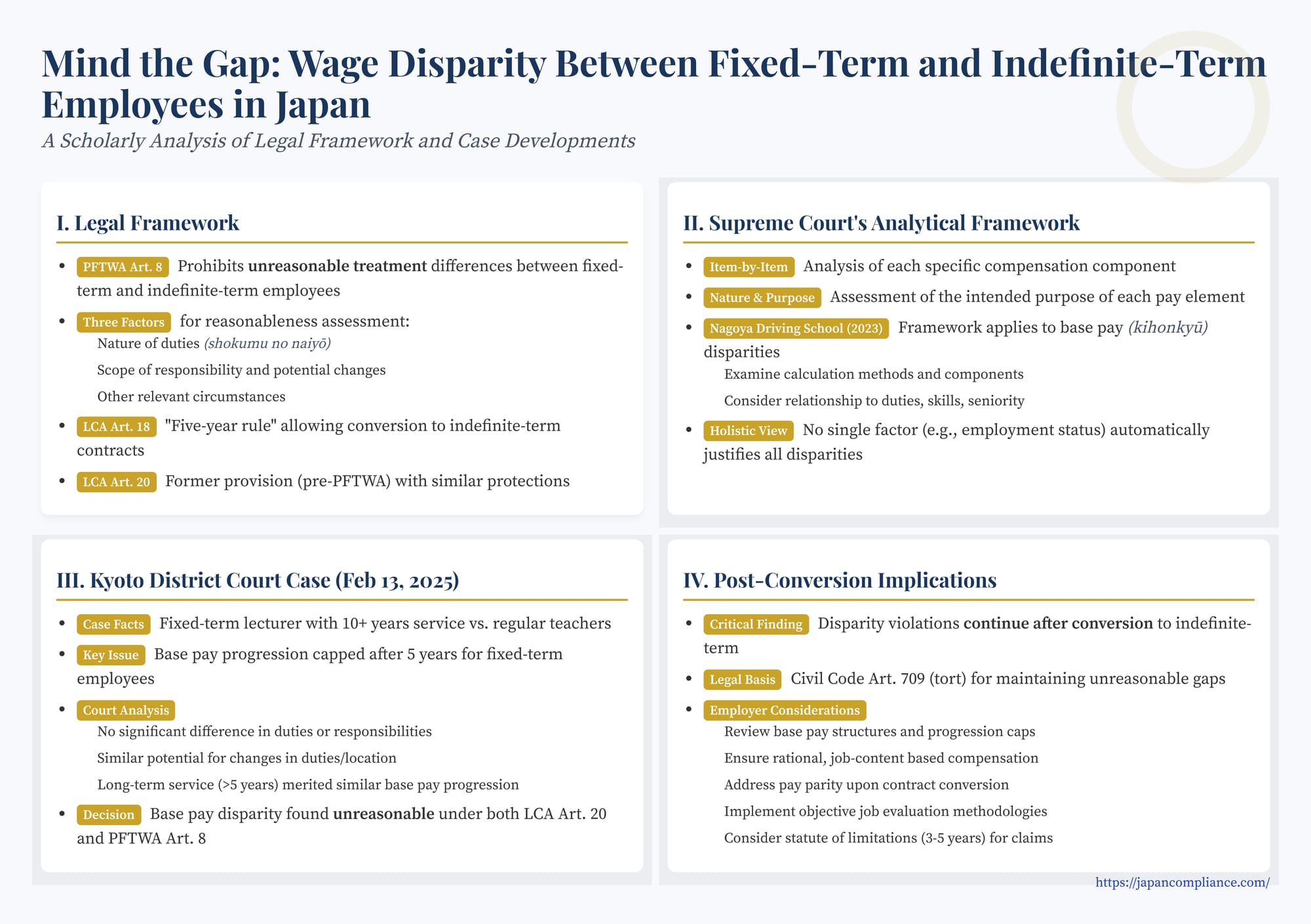

TL;DR: Japan’s Part-Time/Fixed-Term Employment Act and key Supreme Court rulings curb unjust wage gaps, but allow differential treatment when objectively reasonable. HR must document duties, responsibility, and career prospects to defend pay structures and avoid litigation.

Table of Contents

- The Legal Framework: Prohibiting Unreasonable Disparities

- Analyzing Wage Disparities: The Supreme Court's Framework

- Lower Court Application: The Educational Institution Case (Kyoto District Court, 2025)

- The Crucial Question: Disparity After Indefinite Conversion

- Implications for Employers Operating in Japan

- Conclusion: Minding the Gap

Japan's labor market, like many globally, features a diverse workforce operating under various employment arrangements. Alongside traditional indefinite-term employment (muki koyō), often associated with "regular" employees (seishain), the use of fixed-term contracts (yūki koyō) for a significant portion of the workforce is common across many industries. Historically, this distinction often correlated with substantial gaps in wages, benefits, and job security.

In recent years, however, Japan has implemented significant legal reforms aimed at addressing disparities between different employee categories, promoting principles akin to "equal pay for equal work." Central to this effort is the Act on Improvement of Personnel Management and Conversion of Employment Status for Part-Time Workers and Fixed-Term Workers (commonly known as the Part-Time and Fixed-Term Work Act or PFTWA), which prohibits unreasonable differences in treatment.

Navigating this evolving landscape requires employers, including foreign companies operating in Japan, to understand how courts interpret "unreasonable disparities," particularly concerning fundamental elements like base pay (kihonkyū). Furthermore, the interaction between these rules and the right of long-term fixed-term employees to convert to indefinite-term contracts raises critical questions about ongoing wage structures. A recent landmark district court decision sheds light on these complex issues, signaling increased scrutiny of pay practices and potential liability even after contract conversion.

The Legal Framework: Prohibiting Unreasonable Disparities

Several key pieces of legislation govern the treatment of fixed-term and indefinite-term employees:

- Part-Time and Fixed-Term Work Act (PFTWA):

- Article 8 (Prohibition of Unreasonable Treatment): This is the core provision. It forbids treating a fixed-term (or part-time) worker differently from a comparable indefinite-term, full-time ("regular") employee regarding any aspect of their treatment (wages, benefits, education, etc.) if the difference is found to be unreasonable.

- Factors for Reasonableness Assessment: The determination of unreasonableness considers:

- (a) The nature of the workers' duties (shokumu no naiyō).

- (b) The scope of responsibility associated with those duties and the range of potential changes in duties and work location (tōgai shokumu no naiyō oyobi haichi no henkō no hani).

- (c) Other relevant circumstances.

- Item-by-Item Analysis: Crucially, the comparison is made for each specific component of treatment (e.g., base pay, specific allowances, bonuses, benefits). A difference in one item cannot automatically justify a difference in another. The nature and purpose of each specific treatment must be considered in light of factors (a), (b), and (c).

- Labor Contract Act (LCA) - Article 20 (Former):

- Before the PFTWA fully came into effect (April 1, 2020, for large companies; April 1, 2021, for SMEs), the former Article 20 of the LCA contained a similar prohibition against unreasonable disparities specifically for fixed-term versus indefinite-term employees. Many key court precedents were decided under this provision.

- Labor Contract Act (LCA) - Article 18 (Indefinite Conversion Rule):

- Known as the "five-year rule," this article grants fixed-term employees whose total contract period (under repeated renewals with the same employer) exceeds five years the right to request conversion to an indefinite-term contract. Upon such a request, the employer is deemed to have accepted, transforming the contract into one without a fixed term, generally effective from the day after the current fixed term ends. The terms and conditions (except for the contract duration) typically carry over from the previous fixed-term contract unless otherwise agreed.

Analyzing Wage Disparities: The Supreme Court's Framework

For several years, the primary battleground for unreasonable disparity claims under former LCA Article 20 involved various allowances and benefits (e.g., commuting allowance, perfect attendance allowance, housing allowance, retirement benefits, bonuses). A series of landmark Supreme Court decisions in 2018 and 2020 (involving companies like Japan Post, Osaka Medical College, and Metro Commerce) established a consistent analytical framework:

- Focus on Nature and Purpose: The reasonableness of any difference in treatment must be evaluated by examining the nature and purpose of the specific allowance or benefit in question.

- Consideration of the "Three Factors": This purpose must then be assessed in light of the relevant differences (or lack thereof) between the fixed-term and indefinite-term employees concerning (a) duties, (b) scope of change in duties/location, and (c) other circumstances.

- No Single Factor is Determinative: The court emphasized a holistic evaluation, rejecting arguments that certain factors (like the expectation of long-term service for regular employees) automatically justified all disparities.

This framework placed a heavy burden on employers to articulate clear, rational justifications for each specific difference in pay or benefits, tying them directly to the purpose of the component and actual differences in work realities.

Extending the Framework to Base Pay:

While allowances were the initial focus, the question remained whether significant disparities in base pay (kihonkyū) could also be deemed unreasonable. The Supreme Court addressed this in the Nagoya Jidōsha Gakkō (Nagoya Driving School) case (Supreme Court, July 20, 2023). It confirmed that the "nature and purpose" analysis framework does apply to base pay. Assessing the reasonableness of base pay disparities requires analyzing the specific components, calculation methods, and intended purposes of the base pay systems for both fixed-term and indefinite-term employees (e.g., reflecting job duties, skills, seniority, performance) and comparing these against the "three factors" (duties, scope of change, other circumstances).

Lower Court Application: The Educational Institution Case (Kyoto District Court, Feb 13, 2025)

A significant application of this framework occurred in a Kyoto District Court case decided on February 13, 2025. This case involved a full-time fixed-term lecturer at a private high school operated by an educational institution (referred to here as "Institution Y"). The lecturer ("Employee X") had worked continuously for over a decade under renewed one-year contracts before converting to an indefinite-term contract under LCA Article 18.

The core issue was the base pay disparity. Employee X's base salary progression was capped after five years of service, resulting in a substantial and growing gap compared to indefinite-term "regular" teachers (sen'nin kyōin) of similar age and experience employed by Institution Y.

The Kyoto District Court found this disparity unreasonable, violating both former LCA Article 20 and current PFTWA Article 8 for the period before X's contract conversion. Its detailed reasoning provides valuable insight:

- Analyzing Base Pay Components: The court first analyzed the nature and purpose of base pay for both groups.

- Regular Teachers: Their base pay was found to be a composite reflecting age (implicitly linked to experience/cost of living), job capability/skill (shokunōkyū), and rewards for long-term contribution/service (seniority/merit elements). It was less tied to specific assigned duties, as separate allowances covered those aspects (e.g., position allowances).

- Fixed-Term Lecturers (Employee X): Their base pay structure primarily reflected capability and years of service, but critically, only up to a maximum of five years. It lacked the ongoing age-related and long-term service reward components inherent in the regular teachers' system.

- Comparing Work Realities (The Three Factors): The court then compared Employee X's situation with that of comparable non-managerial regular teachers:

- Duties & Responsibilities: Found no significant differences in the actual job content and level of responsibility during the relevant period.

- Scope of Change: Determined that the potential scope for changes in job duties or work location was not meaningfully different between the two groups.

- Other Circumstances: Acknowledged differences in recruitment processes and potential future pathways to management roles but deemed these insufficient to justify the observed gap in current base pay for substantially similar work performed over many years.

- Finding of Unreasonableness: The court concluded that since Employee X had worked long-term (well beyond five years) and performed duties similar to regular teachers, the underlying purposes of the regular teachers' base pay components (reflecting age, capability developed over time, and long-term service) were logically applicable to Employee X as well. Therefore, Institution Y's system, which capped Employee X's base pay progression after five years while comparable regular teachers' pay continued to rise based on age and tenure, lacked rationality and created an unreasonable, widening disparity.

The Crucial Question: Disparity After Indefinite Conversion

Perhaps the most groundbreaking aspect of the Kyoto District Court decision was its analysis of the situation after Employee X converted to an indefinite-term contract on April 1, 2022 (coinciding with a transfer to an administrative role, which the court found permissible).

The PFTWA Article 8 prohibits unreasonable disparities between fixed-term/part-time workers and indefinite-term/full-time workers. Once Employee X became an indefinite-term employee, Article 8 arguably ceased to apply directly to comparisons between X and other indefinite-term employees (like the regular teachers or regular administrative staff). The employer might argue that any remaining pay difference was simply a legacy issue or reflected a different (post-conversion) job role.

However, the court rejected this narrow view. It held that even after the conversion to an indefinite contract, Institution Y's continued payment of a significantly lower wage to Employee X compared to other comparable indefinite-term employees (in this instance, regular administrative staff, given X's transfer) constituted an illegal tort under Article 709 of the Civil Code.

The court's rationale was that the unreasonableness of the wage disparity, established during the fixed-term period based on the lack of justification concerning pay purposes and job realities, did not simply vanish upon conversion. Allowing the employer to perpetuate this unjustified gap indefinitely would undermine the protective intent of the indefinite conversion rule (LCA Art. 18). While PFTWA Article 8 might not directly apply, maintaining such a disparity could potentially violate broader legal principles of fairness, potentially constituting an abuse of rights or violating public order and good morals (Civil Code Art. 90), thus grounding the tort claim.

Implications for Employers Operating in Japan

This district court decision, while potentially subject to appeal, sends a strong signal and has significant implications for employers managing diverse workforces in Japan:

- Base Pay is Not Immune: Significant disparities in base pay between fixed-term and indefinite-term employees performing similar work are subject to rigorous scrutiny. Employers must have clear, objective justifications rooted in the specific nature and purpose of their base pay systems and demonstrable differences in duties, responsibilities, or the scope of potential changes. Simply pointing to different contract types or potential future career paths is unlikely to suffice, especially for long-serving fixed-term staff.

- Scrutiny of Pay Progression: Pay systems that cap the progression of fixed-term employees after a certain number of years while comparable indefinite-term employees continue to advance based on age or tenure are particularly vulnerable to challenge, especially if the fixed-term employees are routinely renewed well beyond the cap period.

- Post-Conversion Pay Parity is Critical: The right to convert to an indefinite-term contract under LCA Article 18 implies more than just job security; it also necessitates a review of the employee's terms and conditions, particularly compensation. Employers cannot simply maintain converted employees on their previous, potentially lower, fixed-term pay scales if those scales create an unreasonable disparity compared to other indefinite-term employees in similar roles or with similar tenure/experience within the company. Creating separate, permanently inferior pay tracks for converted employees carries substantial legal risk. A tort-based claim for damages appears viable if unreasonable gaps persist post-conversion.

- Need for Rational Compensation Structures: Employers should review their compensation systems to ensure that differences between employee categories are based on rational, consistently applied criteria linked to job content, skills, responsibilities, and performance, rather than primarily on employment status (fixed-term vs. indefinite-term).

- Job Evaluation Importance: Implementing objective job evaluation methodologies can help establish the relative value of different roles and provide a more defensible basis for pay differentiation than relying solely on contract type labels.

- Statute of Limitations: While claims can be significant, note that tort claims for damages related to past wage disparities are subject to a statute of limitations (typically 3 years under the Civil Code from when the employee becomes aware of the damage and the liable party, though potentially 5 years if framed as a contract-related claim post-conversion).

Conclusion: Minding the Gap

The legal landscape governing employment relationships in Japan is evolving, with increasing emphasis on fairness and reducing unreasonable disparities between fixed-term and indefinite-term workers. Landmark Supreme Court cases and subsequent lower court decisions, like the one from the Kyoto District Court in February 2025, demonstrate that courts are willing to delve deeply into the nature and purpose of compensation components, including base pay, to assess the reasonableness of differences.

Crucially, the protection against unreasonable treatment doesn't necessarily end when a fixed-term employee exercises their right to convert to an indefinite contract. The potential for ongoing tort liability for maintaining unjustified wage gaps post-conversion adds a significant dimension to managing converted employees. For businesses operating in Japan, this necessitates a proactive and holistic review of compensation structures across all employee categories. Ensuring rational justification for pay differences, particularly for base pay and long-term employees, and carefully managing the terms and conditions of converted employees are essential steps to mitigate legal risks and foster a fairer, more equitable workplace aligned with the direction of Japanese labor law.

- Engaging Japan’s Freelance Workforce: The New Freelance Protection Act and Best Practices for Contracting

- Workforce Management in Japan: Tackling Indirect Discrimination and the New Freelance Act

- When Accidents Happen: Workers' Compensation for Non-Traditional Employees in Japan

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare — Q&A on Equal Pay for Fixed-Term Workers

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/koyou_roudou/koyou/kantoku/