Merger Control in Japan: Understanding Economic Analysis Tools like UPP/GUPPI

TL;DR

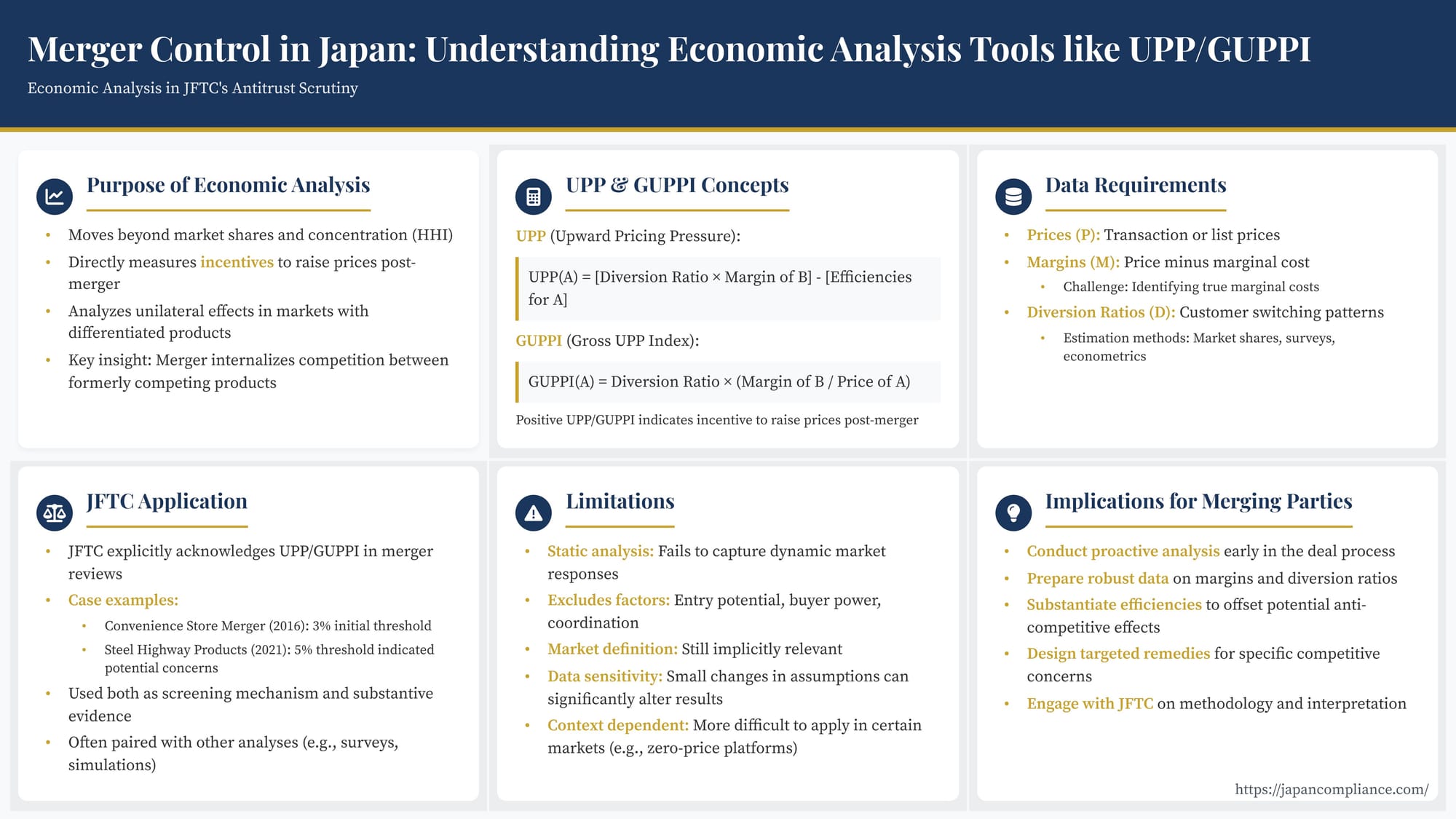

- Japan’s JFTC increasingly uses UPP/GUPPI to gauge unilateral price-rise incentives when rivals merge.

- High diversion ratios + high margins → large GUPPI; 5 % often triggers deeper review.

- Reliable inputs—prices, margins, diversion—are critical; efficiencies can offset pressure in a full UPP.

- These tools complement, not replace, market-definition, entry analysis, and qualitative evidence.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Economic Analysis in Antitrust

- Why UPP/GUPPI? Predicting Incentives

- How UPP Works

- GUPPI: A Simplified Screening Index

- Data Needs & Estimation Challenges

- Use by the JFTC: Case Examples

- Limits & Complementary Evidence

- Practical Advice for Merging Parties

- Conclusion: A Key—but Partial—Tool

Introduction: Economic Analysis in Antitrust Scrutiny

Merger control regimes around the world aim to prevent transactions that are likely to substantially lessen competition and harm consumers, typically through increased prices, reduced output, or diminished innovation. In Japan, the Antimonopoly Act (AMA) prohibits mergers that may result in a substantial restraint of competition in any particular field of trade, with the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) responsible for reviewing transactions exceeding certain thresholds.

Historically, merger analysis heavily relied on defining relevant markets and calculating market shares and concentration levels (like the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index or HHI). While these structural indicators remain important, competition authorities globally, including the JFTC, increasingly employ more sophisticated economic analysis tools to predict the potential competitive effects of a merger more directly, especially concerning "unilateral effects." Unilateral effects occur when the merger eliminates substantial competition between the merging parties themselves, enabling the merged entity to profitably raise prices or reduce quality/innovation on its own, even without coordinating with remaining competitors.

Among the key tools used to assess unilateral effects, particularly in markets with differentiated products (where brands, features, or locations make products imperfect substitutes), are Upward Pricing Pressure (UPP) analysis and its simpler variant, the Gross Upward Pricing Pressure Index (GUPPI). Understanding these tools is becoming increasingly important for businesses contemplating mergers that may attract JFTC scrutiny. This article provides an overview of UPP and GUPPI, explaining their underlying logic, data requirements, application within the JFTC's framework, limitations, and implications for merging parties.

Why Economic Analysis? Predicting Post-Merger Incentives

The core objective of using economic analysis like UPP/GUPPI in merger review is to move beyond static market structures and analyze the dynamic incentives facing the merged firm. A horizontal merger combines the ownership of previously competing products or services. This internalization of competition changes the calculus for pricing decisions.

Before the merger, if Firm A raised the price of its Product 1, some customers might switch to Firm B's competing Product 2. Firm A loses these sales entirely. After Firm A and Firm B merge, if the merged entity raises the price of Product 1, some switching customers will now divert to Product 2, which is also owned by the merged entity. The profit margin earned on these recaptured sales to Product 2 creates an incentive for the merged firm to raise the price of Product 1 – this is the fundamental insight captured by UPP analysis.

UPP and GUPPI attempt to quantify this newly created incentive, providing a more direct assessment of potential price increases than market shares alone, especially where products are differentiated and compete closely.

Understanding Upward Pricing Pressure (UPP)

UPP analysis directly measures the predicted pressure on the price of one of the merging firm's products (say, Product A) following the merger. It balances the upward pressure created by recapturing sales diverted to the merging partner's product (Product B) against the downward pressure that might result from merger-specific cost savings (efficiencies).

Conceptually, the UPP for Product A can be thought of as:

UPP (Product A) = [Profit Gained from Sales Diverted to Product B] - [Cost Savings for Product A]

Let's break down the components:

- Profit Gained from Diverted Sales: This depends on two key factors:

- Diversion Ratio (Dab): This measures the proportion of sales lost by Product A (due to a small hypothetical price increase) that are captured by the merging partner's Product B. A high diversion ratio indicates that Products A and B are close substitutes in the eyes of consumers.

- Profit Margin of Product B (Mb): This is the price of Product B minus its marginal cost of production. A higher margin on the product capturing the diverted sales creates a stronger incentive to raise the price of the other product.

The upward pressure component is essentially(Dab * Mb).

- Marginal Cost Savings / Efficiencies (Ea): The merger might allow the combined firm to produce Product A more cheaply due to economies of scale, rationalized production, or other synergies. These marginal cost savings create a downward pressure on price, potentially offsetting the upward pressure from diverted sales.

Interpretation:

- If UPP(A) is positive, it indicates a net incentive for the merged firm to raise the price of Product A post-merger.

- If UPP(A) is negative, it suggests that efficiencies might be sufficient to counteract the incentive to raise prices due to eliminated competition.

- The magnitude of the positive UPP value gives an indication of the strength of the upward pricing pressure.

Gross Upward Pricing Pressure Index (GUPPI): A Simplified Screen

Calculating merger-specific efficiencies accurately can be complex and contentious. GUPPI is a simplified metric that focuses solely on the price-increasing incentive created by the elimination of competition between the merging products, ignoring any potential efficiencies.

Conceptually:

GUPPI (Product A) = [Profit Gained from Sales Diverted to Product B] / [Price of Product A]

Or, more commonly expressed as:

GUPPI (Product A) = Dab * (Mb / Pa)

Where Dab is the diversion ratio from A to B, Mb is the margin of Product B, and Pa is the price of Product A. Mb / Pa represents the percentage margin of Product B.

Use and Interpretation:

- GUPPI is often used as an initial screening tool. If GUPPI values are low, it suggests that even without considering efficiencies, the incentive to raise prices might be limited.

- Competition authorities in various jurisdictions sometimes use indicative thresholds for GUPPI (e.g., 5% or 10%). Values exceeding these thresholds may trigger closer scrutiny but are not determinative of illegality. The JFTC has referenced a 5% threshold in published case summaries as potentially indicating competitive concerns.

- Because it ignores efficiencies, GUPPI provides an estimate of the gross upward pressure; the net effect on prices could be lower (or even negative) if significant efficiencies exist (which would be captured by a full UPP analysis).

Data Requirements and Estimation Challenges

Applying UPP and GUPPI requires reliable data on three key inputs: prices, margins, and diversion ratios. Obtaining and validating this data presents practical challenges.

1. Prices (P): Usually the most straightforward input, based on actual transaction prices or list prices, depending on the industry.

2. Margins (M): Calculating the relevant profit margin (Price - Marginal Cost) is often difficult.

* Marginal Cost: The cost of producing one additional unit is the theoretically correct measure but is rarely directly observable from standard accounting data.

* Proxies: Average Variable Cost (AVC) is often used as a proxy for marginal cost. However, determining which costs are truly variable versus fixed over the relevant time horizon for a pricing decision can be debated. Legal commentary highlights that excluding costs with variable characteristics, even if classified as fixed for accounting (e.g., certain advertising or R&D expenses crucial for maintaining differentiation), could potentially underestimate the true marginal cost and thus overestimate the margin and the resulting UPP/GUPPI. Careful consideration of the specific business's cost structure is needed.

* Accounting Data: Relying solely on accounting data provides an approximation; the economic concept of marginal cost may differ.

3. Diversion Ratios (D): Estimating how customers would switch between products in response to a price change is perhaps the most challenging aspect. Common methods include:

* Market Shares: A simple approach assumes diversion is proportional to market shares among alternatives. However, this may not accurately reflect substitution patterns, especially if some products are much closer substitutes than others. It might overestimate diversion if customers switch outside the defined market or underestimate it if the merging products are particularly close competitors. Using appropriate, recent market share data is crucial, avoiding periods with unusual economic conditions.

* Customer Surveys: Asking customers directly about their purchasing behavior and hypothetical switching patterns in response to price changes. Well-designed surveys can provide valuable insights but are susceptible to biases and hypothetical responses may not reflect real-world behavior. Pilot testing is recommended.

* Econometric Analysis: Using statistical techniques on historical sales and pricing data to estimate demand elasticities and cross-elasticities, from which diversion ratios can be derived. This is often the most sophisticated approach but requires extensive, high-quality data and complex modeling.

The reliability of UPP/GUPPI analysis heavily depends on the quality and robustness of the underlying data and the chosen estimation methods. Merging parties and the JFTC often engage in detailed discussions about these inputs.

UPP/GUPPI in the JFTC's Merger Review Framework

The JFTC explicitly acknowledges the use of economic analysis, including UPP/GUPPI, in its merger reviews, integrating it with the framework set out in its Merger Guidelines.

- Assessing Unilateral Effects: UPP/GUPPI directly inform the assessment of potential unilateral effects. High diversion ratios and margins between the merging parties' products, leading to high UPP/GUPPI values, indicate that the parties are close competitors and the merger removes a significant competitive constraint. This relates to Guideline factors concerning the degree of differentiation and substitution between products.

- Evaluating Efficiencies: While GUPPI ignores efficiencies, a full UPP analysis requires their quantification. The JFTC's Guidelines state that the authority will consider efficiencies, but generally only those that are merger-specific, likely to be achieved, verifiable, and potentially sufficient to counteract anti-competitive effects (e.g., by leading to lower costs passed on to consumers). A negative UPP calculation could support an efficiency defense.

- Transparency and Case Examples: The JFTC has increased transparency regarding its use of economic analysis. Published case summaries provide insights into practical application:

- Convenience Store Merger (2016): GUPPI was used as a tool to screen numerous local geographic areas where the competitive impact might be relatively large. Customer surveys were conducted to estimate diversion ratios for specific store locations. Areas showing higher GUPPI values (one group averaged 4.8%, exceeding the initial 3% screen) were subject to more detailed examination.

- Steel Highway Products Merger (2021): The JFTC calculated GUPPI using two methods (customer surveys and market shares) for different products (guardrails, guard pipes, etc.). It explicitly mentioned a 5% threshold, noting that GUPPI values generally exceeding this for guardrails suggested potential competitive concerns, while values below 5% for guard pipes did not. This analysis, alongside a simple merger simulation estimating price effects, informed the JFTC's assessment.

These examples show the JFTC utilizing GUPPI both as a screening mechanism and as quantitative evidence supporting its substantive analysis, often in conjunction with other methods like surveys or simulations.

Limitations and the Need for Complementary Analysis

While valuable, UPP and GUPPI analyses have inherent limitations and should not be viewed as conclusive proof of competitive effects. Legal and economic commentary emphasizes several caveats:

- Static Analysis: The basic UPP/GUPPI framework is static. It typically assumes that competitors' prices and product offerings remain unchanged post-merger. It doesn't capture dynamic responses like competitors repositioning their products to compete more aggressively, or the merged firm itself repositioning products, which could either mitigate or exacerbate competitive concerns.

- Exclusion of Other Factors: The standard analysis doesn't explicitly incorporate factors like the potential for new entry into the market, the bargaining power of large buyers (buyer power), or coordinated effects (where the merger makes collusion among remaining firms more likely). These require separate assessment under the Merger Guidelines.

- Market Definition Still Matters: While sometimes presented as an alternative to formal market definition, the interpretation of UPP/GUPPI results often implicitly relies on assumptions about the relevant set of competing products used to calculate diversion ratios. Furthermore, assessing factors like entry or buyer power often requires defining the relevant market.

- Data Sensitivity: Results can be sensitive to the underlying data and estimation methods used for margins and diversion ratios. Small changes in assumptions can sometimes lead to significantly different UPP/GUPPI values.

- Context is Crucial: The interpretation of UPP/GUPPI values should always be done within the broader context of the industry, market dynamics, and other qualitative evidence.

- Specific Market Challenges: Applying these tools straightforwardly can be difficult in certain contexts, such as zero-price digital platforms (where price increases aren't the primary concern) or mergers involving potentially failing firms (where the competitive counterfactual is complex).

Therefore, UPP/GUPPI analysis should be seen as one piece of the puzzle, complementing, rather than replacing, traditional merger analysis tools like market definition, concentration measures, and the assessment of qualitative evidence (e.g., internal company documents assessing competition, customer testimony, industry reports).

Implications for Merging Parties

For companies considering mergers subject to JFTC review, particularly horizontal mergers involving competing, differentiated products:

- Conduct Proactive Analysis: It is often advisable to conduct internal UPP/GUPPI assessments early in the deal process to anticipate potential JFTC concerns. This can inform deal strategy and identify areas needing further justification.

- Engage with the JFTC: Be prepared to discuss the methodology, data sources, and results of any economic analyses (yours or the JFTC's). Transparency and robust data can strengthen your position. Having credible estimates of margins and diversion ratios is crucial.

- Substantiate Efficiencies: If relying on efficiencies to offset potential anti-competitive effects indicated by GUPPI, be prepared to provide detailed, verifiable evidence that meets the JFTC's standards (merger-specificity, likelihood, etc.). A quantitative UPP analysis incorporating these efficiencies can be persuasive.

- Consider Remedies: If high UPP/GUPPI values indicate significant competitive concerns, economic analysis can potentially help in designing targeted remedies, such as divesting specific overlapping products or assets that are the primary drivers of the upward pricing pressure.

Conclusion: A Valuable Tool in the JFTC's Toolkit

UPP and GUPPI have become established tools in the assessment of unilateral effects in merger reviews globally and are increasingly utilized by the JFTC in Japan. They offer a valuable framework for directly quantifying the incentive for a merged firm to raise prices by internalizing competition between differentiated products, moving beyond purely structural analyses. As demonstrated by JFTC case examples, GUPPI, often using indicative thresholds, serves as a useful screening device, while a full UPP analysis allows for the incorporation of potential efficiency defenses.

However, these tools are not a substitute for comprehensive competitive analysis. Their limitations—being static, data-sensitive, and excluding factors like entry or dynamic responses—mean they must be interpreted cautiously and complemented by traditional market analysis and qualitative evidence. For merging parties, understanding the principles behind UPP/GUPPI, proactively gathering relevant data, and being prepared to engage with the JFTC on economic analyses are essential components of navigating the Japanese merger control process successfully. The trend suggests that the sophistication and importance of economic analysis in JFTC reviews will likely continue to grow.

- Human Rights in Japanese Supply Chains: Contractual Strategies and Legal Liabilities

- Japan’s 5-Year Rule for Fixed-Term Contracts: Avoiding Pitfalls for Employers

- Employee Inventions in Japan: Rights, “Reasonable Benefit,” and Procedures

- JFTC | “Guidelines to Application of the Antimonopoly Act Concerning Review of Business Combinations”

https://www.jftc.go.jp/en/legislationgls/antimonopoly_guidelines/files/2023_merger_guidelines.pdf - JFTC | Press Release Archive: Cases Citing GUPPI/UPP Analysis

https://www.jftc.go.jp/en/pressreleases/index.html