Memory vs. Truth: How Japan's High Court Defined Perjury Over a Century Ago

When a witness takes the stand in a court of law, they swear an oath to tell the truth. But what, precisely, is the "truth" that a witness is bound to tell? Is it the objective, factual reality of what happened? Or is it the honest, subjective contents of their own memory? This philosophical question has profound legal consequences. What if a witness deliberately lies, but their statement, by pure chance, turns out to be objectively true? Conversely, what if a witness testifies honestly and faithfully according to their memory, but their memory is mistaken? Which of these scenarios constitutes the crime of perjury?

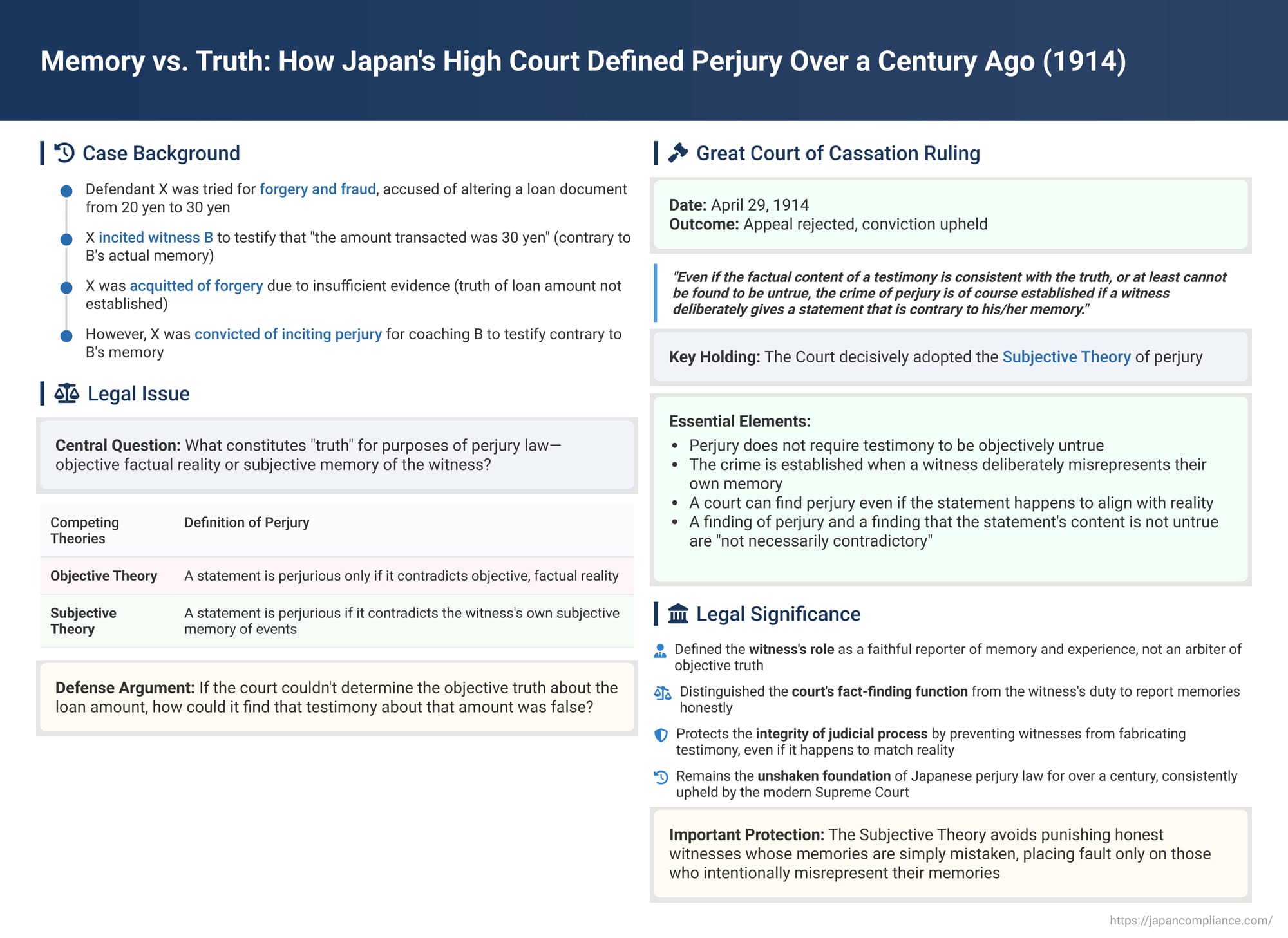

This fundamental question was answered in a landmark decision by Japan's Great Court of Cassation (the predecessor to the modern Supreme Court) on April 29, 1914. The ruling, which has stood as the unshakable foundation of Japanese perjury law for over a century, established that for a witness, the only legally relevant truth is the truth of their own memory.

The Facts: The Forgery Trial and the Coached Witness

The case arose from an underlying criminal trial for forgery and fraud.

- The Underlying Case: The defendant, X, was on trial, accused of altering a loan document from 20 yen to 30 yen and then fraudulently collecting the higher amount.

- The Incitement: To defend against these charges, X, through two intermediaries, incited a witness, B, to give specific testimony in the fraud trial. B was coached to testify that, "I remember that the amount transacted was 30 yen, but I do not remember whether a separate 10 yen loan document in E's name was also given to X at that time."

- The Verdicts: The court ultimately acquitted X of the underlying forgery and fraud charges due to insufficient evidence. This meant that the objective truth of whether the original loan was for 20 yen or 30 yen was never legally established. Despite this, the court found X guilty of the separate crime of inciting perjury for having coached B to give the aforementioned testimony.

The Legal Question: Subjective Memory vs. Objective Reality

The defense appealed the perjury incitement conviction, arguing that it was a logical contradiction.

- The Defense's Argument: How can the court convict someone for inciting "false" testimony when the court itself found there was insufficient evidence to determine the actual truth of the matter? If the underlying fact is unproven, they argued, testimony about that fact cannot be proven to be false.

- The Competing Theories: This argument placed two competing theories of perjury directly at odds:

- The Objective Theory: A statement is perjurious only if it is contrary to objective, factual reality. Under this view, the defense's argument would be strong.

- The Subjective Theory: A statement is perjurious if it is contrary to the witness's own subjective memory of events, regardless of its objective truth.

The Court's Ruling: Memory is the Measure of a Witness's Truth

The Great Court of Cassation rejected the defense's argument and upheld the conviction, explicitly and decisively adopting the Subjective Theory. In its historic ruling, the Court declared:

"Even if the factual content of a testimony is consistent with the truth, or at least cannot be found to be untrue, the crime of perjury is of course established if a witness deliberately gives a statement that is contrary to his/her memory. That is to say, the crime of perjury does not require the testimony to be untrue as a condition."

The Court explained that, therefore, a court could find a defendant guilty of perjury while simultaneously finding that the content of the perjured statement was not, in fact, untrue, and that these two findings are "not necessarily contradictory."

Analysis: The Role of the Witness in the Search for Truth

The Court's adoption of the Subjective Theory is rooted in a clear and specific understanding of the division of labor within the judicial process.

- The Witness's Duty: The role of a witness is not to determine or speculate on the objective truth. Their sole duty is to act as a faithful and honest conduit for their own memories and experiences. They are to report what they saw, heard, and remember, and nothing more.

- The Court's Duty: The role of the judge or jury is to be the ultimate arbiter of fact. They must take the testimony provided by the witness, weigh it against all other pieces of evidence—which may include conflicting testimony, physical evidence, and expert opinions—and, from this totality, determine the objective truth.

- The Harm of Perjury: The crime of perjury, under the Subjective Theory, is therefore a crime against the integrity of this judicial process. When a witness intentionally lies about what they remember, they are corrupting the evidence at its source. They are feeding fabricated data into the court's fact-finding mechanism. This act creates a grave danger of misleading the judge's "free evaluation of evidence" (jiyū shinshō shugi), even if the lie happens to align with reality by coincidence.

The Subjective Theory also avoids the perilous consequences of the Objective Theory.

- The Objective Theory would absurdly absolve a malicious witness who intended to lie but whose statement happened to be true by chance.

- Even more troublingly, it could punish an honest witness who testifies faithfully according to their sincerely held memory, if that memory later turns out to be mistaken. The Subjective Theory correctly places the legal and moral fault on the intentional act of misrepresenting one's memory, not on the fallibility of memory itself.

Legal scholars have further noted that the duty is to report one's memory of their experiences, not what they may later be convinced is the truth. If a witness who saw event A is later persuaded by others that it was actually event B and comes to believe it, their duty is still to testify that they remember seeing A. To testify "I saw B" would be perjury, because it is a statement contrary to their experiential memory.

Conclusion

The Great Court of Cassation's 1914 decision has remained the unshakable foundation of Japanese perjury law for over a century, and its logic is consistently upheld by the modern Supreme Court. It defines perjury not as a crime against objective truth, but as a crime against the integrity of a witness's own memory. The ruling clarifies the role of a witness with profound simplicity: they are not arbiters of reality, but honest reporters of their own perceptions and recollections. By ensuring that this fundamental duty is strictly enforced, the law protects the integrity of the entire judicial fact-finding process from the corrupting influence of testimony that is known by the witness to be a lie.