Membership Optional, Maintenance Mandatory? Japan's Supreme Court on Residents' Associations and Fees

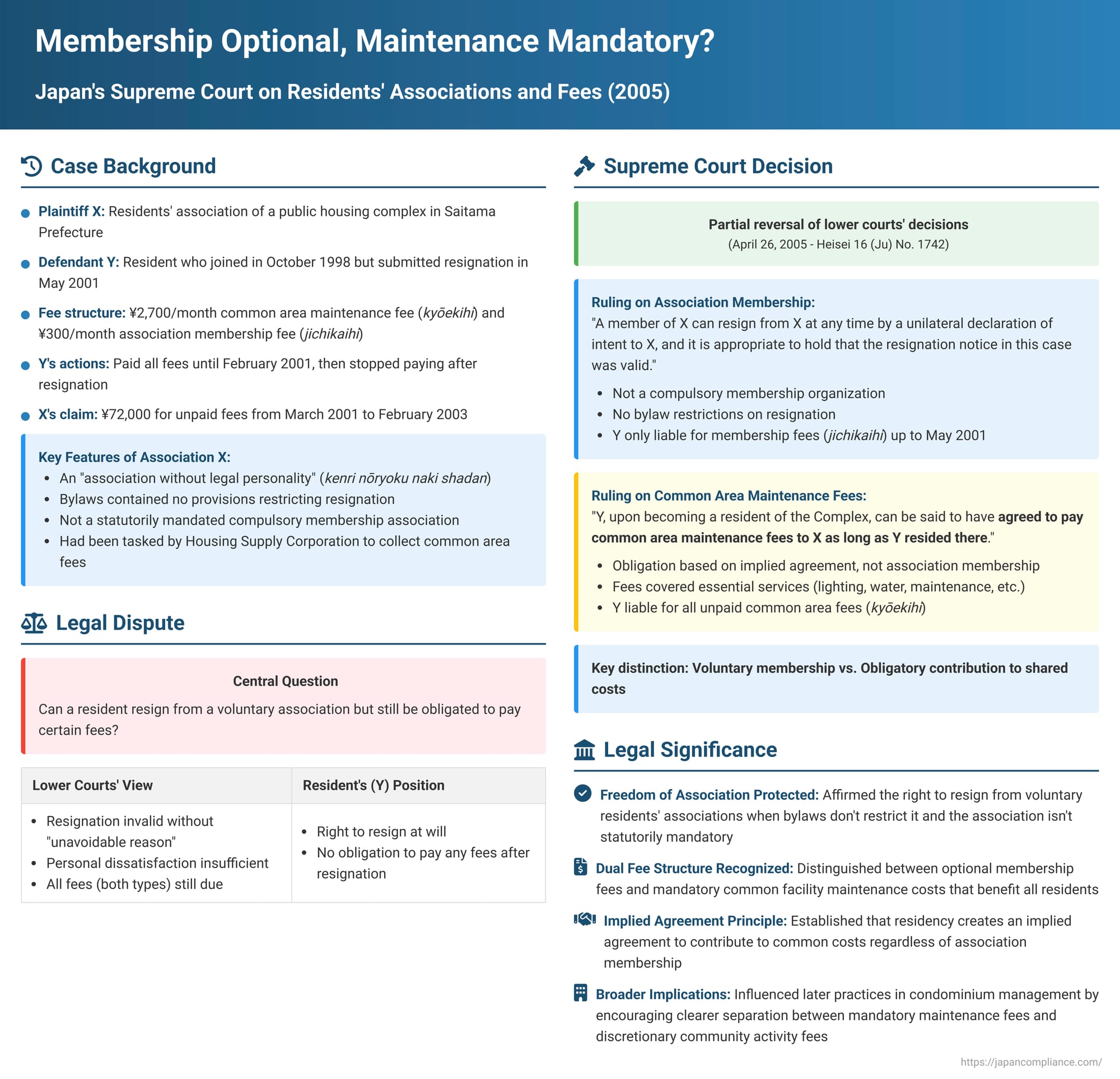

Residents' associations (jichikai) are a common feature of housing complexes in Japan, playing roles in community building, local environment upkeep, and sometimes liaising with property managers. But what happens when a resident, dissatisfied with the association, wishes to leave? Can they freely resign? And upon resignation, are they absolved from all fee obligations, especially those related to the maintenance of common areas they continue to use? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed these questions in a significant judgment on April 26, 2005 (Heisei 16 (Ju) No. 1742), concerning a dispute in a prefectural public housing complex.

The Saitama Public Housing Dispute: A Resident vs. the Association

The plaintiff, X, was the residents' association for "the Complex," a public housing estate comprised of three buildings in Saitama Prefecture. X operated as an "association without legal personality" (kenri nōryoku naki shadan), with its membership consisting of the residents of the Complex. Its stated purposes included fostering fellowship among members and maintaining a comfortable living environment.

The Housing Supply Corporation A, entrusted by the Saitama prefectural government with the management of the Complex, had instructed all residents to pay common area maintenance fees (kyōekihi) to Association X. Association X's bylaws stipulated that it was organized by the residents of the Complex and set the common area maintenance fee at 2,700 yen per month per household, and an association membership fee (jichikaihi) at 300 yen per month per household. Importantly, the bylaws contained no provisions restricting a member's right to resign.

The defendant, Y, became a resident of the Complex on October 1, 1998, and duly joined Association X, paying both the common area maintenance fees and the association membership fees from that month until February 2001. However, citing dissatisfaction with the policies of Association X's leadership, Y submitted a notice of resignation to X on May 24, 2001.

Association X subsequently sued Y for unpaid common area maintenance fees and association membership fees for the period from March 2001 to February 2003, totaling 72,000 yen.

Lower Courts: Resignation Invalid, All Fees Due

The lower courts had found in favor of Association X. The Saitama District Court, while classifying X as a partnership under the Civil Code, noted its similarities to a condominium management association and held Y's resignation invalid because there was no "unavoidable reason" for it. The Tokyo High Court, on appeal, classified X as an association without legal personality but also deemed the resignation invalid. It reasoned that given X's public nature and objectives, resignation based on personal beliefs or feelings was impermissible "as a matter of natural justice" (jōri jō yurusarenai) unless X's operations were significantly unlawful or infringed upon individual rights. Both courts held Y liable for all unpaid fees. Y appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Dual Finding (April 26, 2005): Resignation Valid, but Common Area Fees Still Owed

The Supreme Court partially overturned the lower courts' decisions, making a crucial distinction between the two types of fees:

Part 1: Freedom to Resign from the Voluntary Association (Regarding Jichikaihi)

The Supreme Court first addressed the validity of Y's resignation from Association X and the obligation to pay association membership fees:

- Association X was characterized as an "association without legal personality" established for purposes such as member fellowship, environmental maintenance, and mutual welfare.

- Critically, the Court noted that X was not a compulsory membership organization (kyōsei kanyū dantai).

- Furthermore, its bylaws contained no provisions restricting a member's right to resign.

- Based on these factors, the Supreme Court concluded that "a member of X can resign from X at any time by a unilateral declaration of intent to X, and it is appropriate to hold that the resignation notice in this case was valid".

- The Court stated that "the purposes of X's establishment, its objectives, and its character as an organization do not affect this conclusion".

- Consequently, Y was only liable for the unpaid association membership fees up to the effective date of resignation (May 2001).

Part 2: Obligation to Pay Common Area Maintenance Fees (Kyōekihi) Continues

The Court then turned to the common area maintenance fees, reaching a different conclusion regarding Y's obligation:

- The kyōekihi were defined as costs for maintaining common facilities within the Complex, such as electricity for street and stairway lighting, water for outdoor hydrants, drainage system upkeep, elevator maintenance, and pest control.

- The Housing Supply Corporation A (managing the Complex on behalf of the prefecture) had instructed Association X and all residents that, due to the difficulty of individual residents paying various vendors directly, X would collect the kyōekihi from each resident and make lump-sum payments to the service providers.

- Both Association X and the residents, including Y, had followed this directive; Y had paid kyōekihi to X from October 1998 to February 2001.

- Based on these facts, the Supreme Court found that "Y, upon becoming a resident of...the Complex, can be said to have agreed to pay common area maintenance fees to X as long as Y resided there".

- Therefore, the Court held: "Regardless of whether the resignation notice in this case was valid or not, Y's obligation to pay common area maintenance fees to X does not cease". Y remained liable for all unpaid kyōekihi for the entire period claimed.

Key Distinctions and Underlying Principles

This Supreme Court judgment established important distinctions and principles:

- Voluntary Association Membership vs. Shared Service Costs: The Court clearly separated the voluntary nature of membership in a residents' association (often for social, fellowship, or optional community activities) from the non-optional, practical necessity of all residents contributing to the maintenance and operational costs of shared facilities and services from which they directly benefit.

- Basis of Obligation: The obligation to pay the jichikaihi (association membership fee) stemmed directly from being a member of Association X; thus, it ceased upon valid resignation. In contrast, the obligation to pay the kyōekihi (common area maintenance fee) was found to be based on an agreement (explicit or implied upon moving in and participating in the payment system) linked to continued residency in the Complex and the use of its common facilities.

- Nature of the Association (Voluntary vs. Compulsory): A key factor in permitting resignation from Association X was that it was not a statutorily mandated compulsory membership group, and its own rules did not restrict resignation. This contrasts with, for example, condominium management associations established under the Condominium Ownership Act.

Broader Implications and Relevance

The Supreme Court's 2005 decision has had a lasting impact:

- For Renters' Associations in Public/Private Housing: It provides a clear precedent affirming that residents in rental housing complexes can generally resign from voluntary residents' associations if the bylaws don't prohibit it and the association isn't a legally compulsory body. However, it also confirms that resignation from such an association does not automatically absolve a resident from their obligation to pay for essential common area services, especially if there's an underlying agreement or established practice for such payments.

- Indirect Relevance to Condominiums (Statutory Management Associations):

- It's crucial to note that the freedom-to-resign principle established in this case does not directly apply to statutory condominium management associations (kanri kumiai) formed under Japan's Condominium Ownership Act (COA). For such associations, unit ownership automatically entails membership, and resignation is generally not possible as long as one owns the unit.

- However, the Supreme Court's careful distinction between fees for voluntary association activities (like fellowship) and fees for essential common area maintenance and management is highly relevant to ongoing discussions within the condominium context. There's a recognized need to differentiate between core management expenses (which all unit owners must bear under COA Article 19) and expenses for "community building" or optional activities. This judgment supports the trend towards greater transparency and potentially separate handling of these distinct types of fees, with the latter often being more appropriately managed on a voluntary basis or by a separate, optional residents' group within the condominium. The commentary notes that later revisions to model condominium bylaws by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism moved to clearly separate mandatory management fees from discretionary community activity fees.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2005 decision in the Saitama public housing case skillfully balanced a resident's freedom of association—specifically, the right to dissociate from a voluntary residents' group—with their continuing responsibility as a resident to contribute to the operational costs of the common facilities and services they use. It established that while membership in a non-compulsory association can typically be terminated by unilateral notice if not restricted by bylaws, the obligation to pay for essential shared services often rests on a separate basis, such as an agreement linked to residency, and thus may persist independently of association membership. This ruling provides important guidance for residents' associations, property managers, and residents alike in understanding their respective rights and obligations concerning fees in Japanese housing complexes.