When Treatment Standards Matter: Japan’s Supreme Court on High‑Cost Medical Expense Benefits (1986)

TL;DR

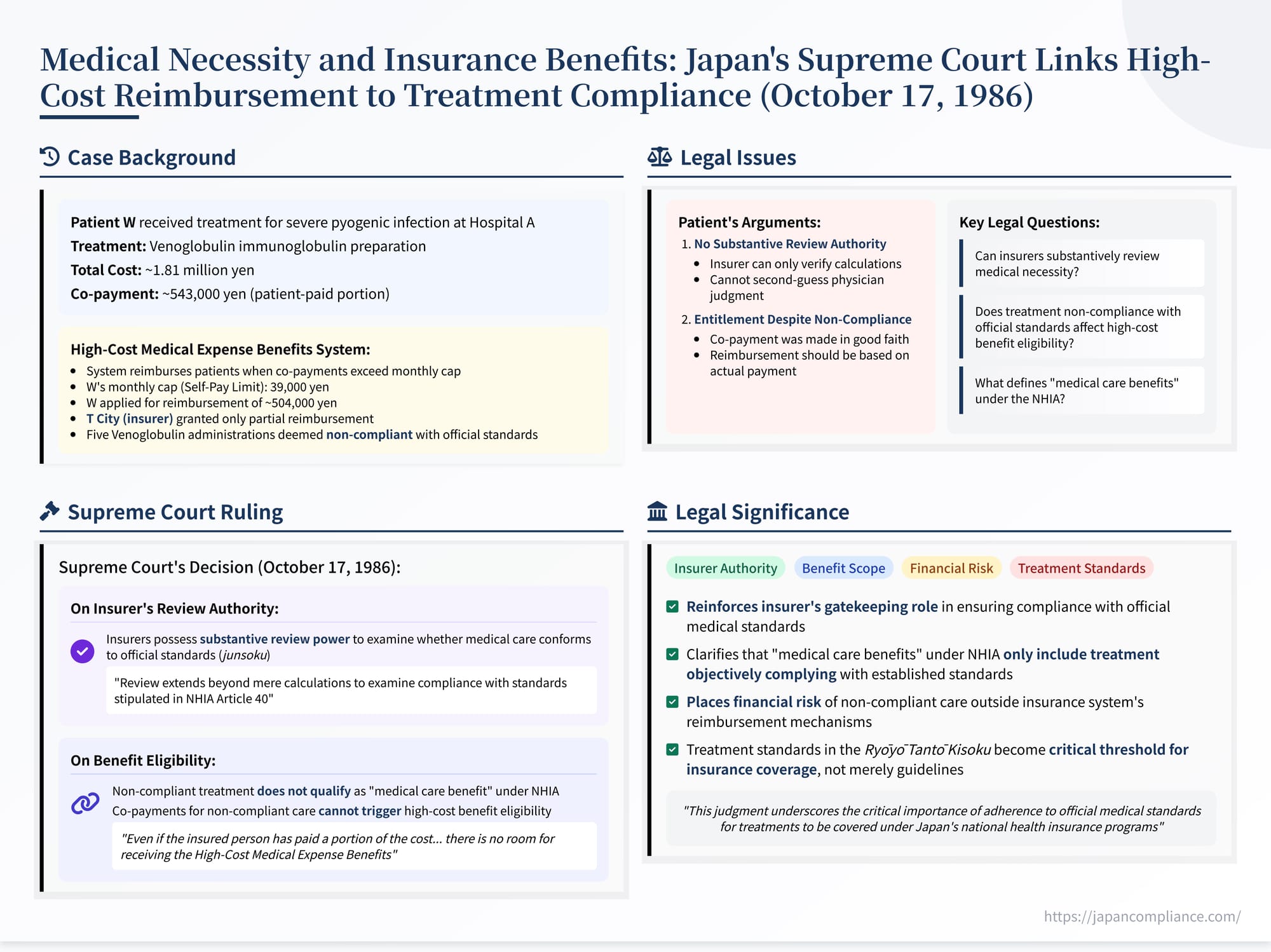

In its 17 October 1986 ruling (Case No. 1986 (Gyo‑Tsu) 68), the Supreme Court of Japan confirmed that insurers may conduct substantive reviews of claimed treatments under the National Health Insurance Act and may deny High‑Cost Medical Expense Benefits when underlying care violates official standards. Non‑compliant care is deemed outside “medical care benefits,” so co‑payments tied to such care are ineligible for reimbursement.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: High Co‑Payments and Disputed Treatment

- The Legal Challenge: Questioning Review Authority and Benefit Eligibility

- The Supreme Court’s Decision (October 17, 1986)

- Implications and Significance

- Conclusion

On October 17, 1986, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a significant ruling in a case involving a challenge to a decision on High-Cost Medical Expense Benefits (高額療養費 - kōgaku ryōyōhi) under the National Health Insurance Act (Case No. 1986 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 68). This judgment addressed fundamental questions about the scope of the insurer's authority to review the appropriateness of medical treatments and, crucially, whether patients are entitled to reimbursement for high co-payments if the underlying medical care received does not conform to official standards. The Court affirmed the insurer's power of substantive review and held that non-compliant treatment falls outside the scope of insured benefits, thereby precluding eligibility for high-cost reimbursement related to that portion of care. This analysis examines the case facts, the legal arguments, and the enduring implications of the Supreme Court's decision.

Factual Background: High Co-Payments and Disputed Treatment

The appellant, W, was an individual insured under Japan's National Health Insurance Act (NHIA). After suffering severe hemorrhaging, W underwent surgery at Hospital A, an accredited insurance medical institution under the NHIA. Following the surgery, W was diagnosed with a serious pyogenic infection. To treat the infection while preventing its worsening, physicians at Hospital A determined that administering an immunoglobulin preparation, Venoglobulin, was necessary and proceeded to administer it until W's condition stabilized.

Hospital A calculated the cost of W's medical care for the month according to the fee schedule regulations established by the Minister of Health and Welfare (as prescribed by NHIA Article 45, Paragraph 2, referencing the Health Insurance Act provisions at the time). The total calculated cost amounted to approximately 1.81 million yen. Under the NHIA, insured individuals are typically responsible for a percentage of their medical costs as a co-payment (一部負担金 - ichibu futankin). W paid Hospital A approximately 543,000 yen, representing this co-payment portion.

Japan's health insurance system includes a safety net mechanism called High-Cost Medical Expense Benefits (kōgaku ryōyōhi), governed by Article 57-2 of the NHIA. This system reimburses insured individuals for the portion of their monthly co-payments that exceeds a statutory cap (the "Self-Pay Limit," which was 39,000 yen per month for W at the time). W applied to the insurer, T City (the appellee), for these benefits, seeking reimbursement of approximately 504,000 yen (the co-payment paid minus the self-pay limit).

However, a complication arose during the review process. T City had delegated the task of reviewing fee claims to the Gifu Prefecture National Health Insurance Medical Fee Review Committee. This committee examined the claim submitted by Hospital A and determined that five specific administrations of Venoglobulin provided to W were not appropriate or necessary according to the standards set forth in the official Rules for Insurance Medical Care Organs and Doctors in Charge of Insurance Medical Care (療養担当規則 - Ryōyō Tantō Kisoku). These rules define the scope and standards for treatment eligible for insurance coverage. The committee concluded that these specific administrations did not qualify as expenses for "medical care benefits" (ryōyō no kyūfu) covered under the NHIA.

Consequently, T City recalculated the eligible medical expenses. It deducted the cost associated with the disallowed Venoglobulin administrations from the total amount claimed by Hospital A, arriving at an adjusted eligible cost of approximately 1.52 million yen. Based on this revised amount, T City determined that W's legally required co-payment should have been approximately 457,000 yen. T City then issued a decision granting W High-Cost Medical Expense Benefits based on this lower co-payment amount – reimbursing W approximately 418,000 yen (457,000 yen minus the 39,000 yen limit). This decision effectively constituted a partial denial (fushikyū shobun) of W's claim, refusing reimbursement for the portion of the co-payment W had actually paid that corresponded to the non-compliant Venoglobulin treatments.

The Legal Challenge: Questioning Review Authority and Benefit Eligibility

W contested T City's partial denial and filed a lawsuit seeking its revocation. The case eventually reached the Supreme Court with two primary legal arguments advanced by W:

- Lack of Substantive Review Authority: W argued that the insurer (T City, acting through its delegated committee) lacked the legal authority under the NHIA to conduct a substantive review of the medical necessity or appropriateness of the treatment provided. W contended that the insurer's review should be limited to verifying calculations and ensuring procedural compliance, and that second-guessing the clinical judgment of the treating physician regarding compliance with the Ryōyō Tantō Kisoku was beyond the insurer's power and potentially violated the constitutional separation of powers.

- Eligibility Despite Non-Compliance: Alternatively, W argued that even if some part of the treatment was deemed non-compliant with the official standards, W had paid the co-payment in good faith based on the treatment received. W asserted entitlement to High-Cost Medical Expense Benefits based on the actual co-payment made, regardless of the subsequent review finding parts of the underlying care non-compliant.

The lower courts (Gifu District Court and Nagoya High Court) rejected W's arguments and dismissed the claim, leading to the appeal before the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (October 17, 1986)

On October 17, 1986, the Supreme Court dismissed W's appeal, affirming the lower courts' decisions. The Court systematically addressed and rejected both of W's main arguments.

1. Affirming the Insurer's Power of Substantive Review:

The Court first addressed the scope of the insurer's review authority under NHIA Article 45, Paragraph 4, which mandates insurers to review and pay claims submitted by medical institutions. The Court definitively held that this review power is not merely formalistic or limited to calculations. It explicitly extends to a substantive examination of whether the medical care provided, for which fees are claimed, actually conforms to the standards (準則 - junsoku) stipulated in NHIA Article 40 (which are detailed in the Ryōyō Tantō Kisoku).

The Court reasoned that the legislative intent for such substantive review was evident from other provisions within the NHIA. Specifically, Article 45, Paragraph 5 allows insurers to delegate review functions to specialized bodies (like the Prefectural Review Committees or the Social Insurance Medical Fee Payment Fund). Articles 87 through 89 detail the establishment and operation of these committees, often composed of medical experts, representatives of insurers, and public interest representatives, equipped to assess the appropriateness of care. The existence of this structured, expert-driven review mechanism, the Court concluded, clearly indicated that the "review" mentioned in Article 45(4) was intended to encompass the substantive medical aspects of the claim, including compliance with official treatment standards.

Therefore, W's argument predicated on the insurer lacking substantive review power was based on a faulty premise and was rejected. The Court found no violation of law in the lower courts' affirmation of this authority.

2. Linking Treatment Compliance to Benefit Eligibility:

The Court then turned to the core issue: the relationship between the compliance of the medical treatment received and the patient's eligibility for insurance benefits, particularly High-Cost Medical Expense Benefits.

The Court laid out the following legal principles under the NHIA system:

- Insurance medical institutions have a duty towards the insurer to provide medical care that conforms to the standards (junsoku) set forth in Article 40.

- Consequently, the scope of medical care that an insured person is entitled to receive as an NHIA "medical care benefit" (ryōyō no kyūfu) under Article 36 is inherently limited by these same standards.

- If a medical treatment provided by an institution, when viewed objectively, does not conform to these official standards, then that specific treatment does not qualify as a "medical care benefit" (ryōyō no kyūfu) as defined and covered by the NHIA.

3. Impact on High-Cost Medical Expense Benefits:

Building on this, the Court drew a direct conclusion regarding High-Cost Medical Expense Benefits (Article 57-2):

- These benefits are specifically designed to alleviate the burden of co-payments made for eligible medical care benefits (ryōyō no kyūfu).

- Therefore, if a treatment received does not qualify as an eligible benefit because it fails to meet the official standards, any co-payment made by the insured person relating to that non-compliant portion cannot trigger eligibility for High-Cost Medical Expense Benefits.

- The Court stated unequivocally: "even if the insured person has paid a portion of the cost to the medical care handling institution under the name of co-payment, there is no room for receiving the High-Cost Medical Expense Benefits stipulated in Article 57-2 thereof."

The Court found the lower courts' reasoning on this point to be correct and found no legal error. W's arguments were characterized as being based on a unique, unsupported interpretation of the law.

Implications and Significance

This 1986 Supreme Court decision carries significant implications for the functioning of Japan's health insurance system and the relationship between patients, providers, and insurers:

- Reinforcement of Insurer's Gatekeeping Role: The judgment firmly establishes the insurer's authority (whether exercised directly or through delegated review bodies) to act as a gatekeeper, ensuring that payments are made only for medical care that meets the officially defined standards of necessity and appropriateness (Ryōyō Tantō Kisoku). This confirms that the review process is not merely about validating bills but about overseeing the substance of care provided under the insurance umbrella.

- Defining the Scope of "Insured Benefits": The ruling clarifies that the term "medical care benefits" (ryōyō no kyūfu) under the NHIA is not synonymous with any treatment a doctor provides. It is specifically limited to care that objectively complies with the established standards. Treatment falling outside these standards, even if provided with therapeutic intent, is not considered an insured benefit.

- Allocation of Financial Risk for Non-Compliant Care: By denying High-Cost Medical Expense Benefits for co-payments related to non-compliant care, the Court effectively places the financial risk of such care (at least concerning the co-payment portion) primarily outside the insurance system's direct reimbursement mechanisms. If care is deemed non-compliant, the insurer is not obligated to cover it, nor is it obligated to reimburse the patient for high co-payments made for it. This implies that the financial consequences of providing or receiving non-standard care must be resolved between the provider and the patient.

- Relevance in Evolving Payment Systems: At the time of this ruling (1986), High-Cost Medical Expense Benefits were typically paid retrospectively to the patient after they had paid the full co-payment at the provider's office. Modern Japanese health insurance systems increasingly utilize mechanisms where patients, by presenting a "Limit Application Certificate" (限度額適用認定証 - Gendogaku Tekiyō Ninteishō), only pay up to their statutory monthly limit at the point of service. The provider then bills the insurer for the remainder, including the high-cost portion. While this "in-kind" benefit system changes the immediate cash flow (potentially shifting the upfront burden of disallowed costs more towards the provider if claims are later reduced), the fundamental principle established by this Supreme Court decision remains valid: eligibility for any insurance payment, whether directly for services or as high-cost benefit relief, is contingent upon the underlying medical care complying with the Ryōyō Tantō Kisoku.

- Unresolved Provider-Patient Issues: The ruling focuses on the insurer-patient relationship regarding high-cost benefits. It does not directly address the separate issue of whether a patient like W, who paid a co-payment for care later deemed non-compliant, could potentially seek a refund of that payment from the provider (Hospital A) based on principles like unjust enrichment or contract law. This provider-patient dimension remains outside the scope of this judgment but is a practical consequence of the ruling's allocation of risk away from the insurer.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision of October 17, 1986, is a foundational ruling in Japanese health law jurisprudence. It confirms that insurers possess the authority to substantively review medical treatments against official standards and, more critically, establishes that medical care failing to meet these standards falls outside the definition of insured "medical care benefits" under the National Health Insurance Act. Consequently, patients cannot claim High-Cost Medical Expense Benefits for co-payments associated with such non-compliant care. This judgment underscores the critical importance of adherence to official medical standards for treatments to be covered under Japan's national health insurance programs and clarifies the financial boundaries of the insurance system when standards are not met.