Mapping the Limits of Transparency: Japan's Supreme Court on Disclosing Preliminary Dam Site Information

Judgment Date: March 25, 1994

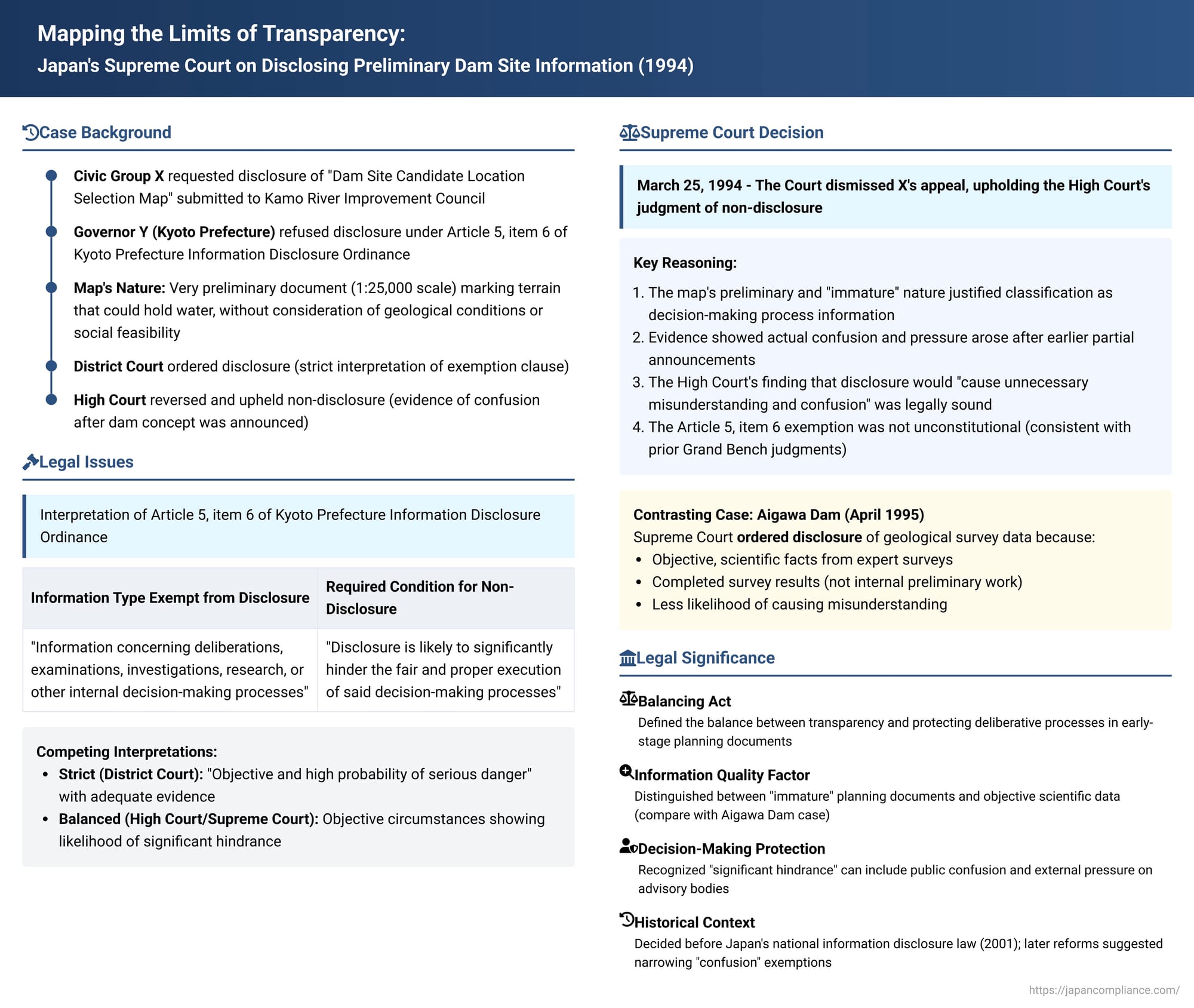

Public access to government information, especially during the early planning stages of major public works projects, is a critical component of democratic accountability and informed citizen participation. However, this principle often clashes with the government's need to conduct internal deliberations and preliminary studies frankly and without undue external pressure or public confusion. A Japanese Supreme Court decision from March 25, 1994 (Heisei 5 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 110), addressed this tension in a case concerning the disclosure of a preliminary map identifying potential dam sites, interpreting a local government's information disclosure ordinance before the advent of a national disclosure law.

The Kamo River Controversy: A Request for a Map

The case originated in Kyoto Prefecture, where X, a civic group, sought the disclosure of a specific document: a "Dam Site Candidate Location Selection Map" (hereinafter, "the map"). This map had been submitted to the Kamo River Improvement Council, an advisory body established by Y, the Governor of Kyoto Prefecture, to gather a wide range of opinions from experts and others regarding the Kamo River improvement plan. The Council's meetings were conducted privately.

The disclosure request was triggered after a press conference following the Council's fifth meeting. At this conference, it was announced that a dam concept was under consideration and that related drawings, including the map, had been presented to the Council. Upon learning this, X filed a request under the Kyoto Prefecture Information Disclosure Ordinance (Showa 63 Kyoto Pref. Ordinance No. 17, hereinafter "the Ordinance") for the disclosure of the map.

Governor Y decided to withhold the map entirely. The legal basis for this non-disclosure was Article 5, item 6 of the Ordinance. This provision exempted from disclosure "information concerning deliberations, examinations, investigations, research, or other internal decision-making processes of the Prefecture or the State, etc., the disclosure of which is likely to significantly hinder the fair and proper execution of said or similar decision-making processes" (often referred to as "information in the decision-making process" or ishi keisei katei jōhō).

The map in question was described as a very preliminary document. It had been prepared by the relevant prefectural department as study material for the dam concept. Using a 1:25,000 topographical map as a base, department staff had identified terrain in the Kamo River basin that could potentially hold water, marking these as dam site candidate locations with reference numbers on a watershed map. Despite its title, the map did not incorporate any consideration of crucial factors such as geological conditions, other natural elements, or the social feasibility of land acquisition. It was, therefore, an "immature" document representing a very early stage of consideration.

The Legal Tug-of-War: Lower Court Battles

X challenged the Governor's non-disclosure decision in court. The Kyoto District Court, in its first instance ruling, sided with X and ordered the map's disclosure. The District Court underscored the importance of the "right to know" (a principle often invoked in information disclosure contexts, though not explicitly a constitutionally enumerated right in Japan in the same way as freedom of speech) and posited that restrictions on disclosure must be based on rational reasons and limited to the necessary minimum. It interpreted the "significant hindrance" clause in Article 5, item 6 of the Ordinance to require an "objective and high probability of serious danger" and found that the Governor had not provided adequate evidence to meet this stringent standard regarding the map.

However, the Osaka High Court, hearing the appeal, reversed the District Court's decision and upheld the Governor's refusal to disclose the map. The High Court based its judgment on several factors: (1) the reasons why the Kamo River Improvement Council meetings were held in private; (2) the current status of the Council's deliberations; (3) the preliminary and unrefined nature of the map itself; and (4) evidence that after the dam concept and the map's submission to the Council were publicly announced, council members and prefectural staff faced approaches and even demands regarding the dam construction, to the extent that some council members expressed a desire to resign. Based on these findings, the High Court concluded that the map constituted "immature information within a decision-making process" and that its disclosure was "likely to cause unnecessary misunderstanding and confusion among residents and significantly hinder the fair and proper conduct of the council's decision-making," thereby falling under the Article 5, item 6 exemption.

The Supreme Court's Verdict (March 25, 1994): Upholding Non-Disclosure

X appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, dismissed X's appeal, thereby affirming the High Court's judgment that upheld the non-disclosure of the map.

The Supreme Court found that, under the facts lawfully established by the High Court, the determination that the map contained information falling under Article 5, item 6 of the Ordinance, and that the Governor's decision to withhold it was therefore lawful, was justifiable and without legal error in its process. The Court also summarily rejected X's argument that Article 5, item 6 of the Ordinance was unconstitutional (allegedly infringing upon Article 21, paragraph 1 of the Constitution, which guarantees freedom of expression, and other constitutional provisions). The Court stated that the constitutionality of such provisions, which allow for the non-disclosure of information within the decision-making processes of governmental bodies if disclosure would significantly hinder such processes, was clear by reference to the reasoning in several of its own prior Grand Bench judgments.

Decoding the "Decision-Making Process Information" Exemption

The central legal issue revolved around the interpretation of Article 5, item 6 of the Kyoto Ordinance, a type of exemption commonly found in information disclosure laws to protect internal governmental deliberations.

The interpretive guidelines for the Kyoto Ordinance itself shed some light on the rationale behind this exemption. They explain that information within an administrative agency's decision-making process, even if it has been formally processed as a document (e.g., signed off, circulated), might still represent only one stage in an ongoing process. Such information can include "immature" data that has not yet been thoroughly examined or discussed internally, or study materials whose accuracy has not been fully vetted. The guidelines suggest that disclosing such preliminary or unrefined information could:

- Cause unnecessary misunderstanding or confusion among the public.

- Unfairly benefit or disadvantage certain users of the information.

- Hinder free and frank exchanges of opinions within the administrative agency.

- Make it difficult to obtain necessary materials for internal review.

It is for these reasons that the Ordinance allows such information to be withheld.

However, legal commentary points out a potential risk: if administrative agencies prioritize their own interest in ensuring the smooth conduct of internal deliberations and interpret this exemption too broadly, it could undermine the overarching goals of the information disclosure system itself, such as promoting open governance and facilitating citizen participation. Therefore, a careful balance is required when deciding on the disclosure of "decision-making process information," involving a case-by-case consideration of the requester's interest in access versus the agency's interest in protecting its deliberative processes. Ideally, from the perspective of fostering transparency and aligning with the spirit of freedom of information, such exemptions should be interpreted narrowly.

Regarding the standard of "significant hindrance" (ichijirushii shishō) required by Article 5, item 6, the commentary suggests that while an abstract risk or mere possibility of hindrance is insufficient—requiring an objective and concrete risk—the very strict standard articulated by the District Court (requiring "objective and high probability of serious danger" supported by "adequate evidence") might have been an overly narrow interpretation of the Ordinance's text. The High Court and the Supreme Court, in contrast, appeared to adopt a more literal, and arguably less stringent, interpretation of "likelihood of significant hindrance," finding the non-disclosure justified based on the objective circumstances presented by the Governor, particularly the actual repercussions following the initial announcement about the dam concept.

X raised other legal points, including the alleged unconstitutionality of Article 5, item 6 and an argument that the legality of the non-disclosure decision should be judged based on the circumstances existing at the time of the conclusion of oral arguments in the fact-finding (lower court) stages. The Supreme Court dismissed these arguments, affirming the High Court's judgment and aligning with established precedents and prevailing scholarly opinion on these matters.

Comparing Cases: Why This Map Stayed Secret but Other Data Was Released

The Supreme Court's decision in the Kamo River map case can be better understood when contrasted with other rulings on similar issues. A notable comparison is the Aigawa Dam litigation in Osaka. In that case, residents sought disclosure of geological survey data related to a planned dam. While the first instance court denied disclosure, the Osaka High Court (in a June 1994 decision, shortly after the Kamo River SC ruling) ordered the disclosure of the geological data. The Supreme Court subsequently upheld this disclosure order (April 1995).

The different outcomes in the Kamo River and Aigawa Dam cases appear to hinge on the nature of the information requested:

- In the Aigawa Dam case, the non-disclosed information was inferred to be objective, scientific facts from geological surveys conducted by experts, along with their objective, scientific analyses. Such information was deemed unlikely to cause misunderstanding in the planning process. Furthermore, this data had been obtained through outsourcing to an external geological survey company, making it a completed survey result rather than a purely internal prefectural document.

- In contrast, the Kamo River map was a very preliminary, internal document created by administrative staff merely by identifying potentially suitable terrain from a topographical map, without any expert review of geology or socio-economic factors. While it indicated the administration's internal thinking about potential dam sites, its immaturity was evident.

Both the Kamo River and Aigawa Dam Supreme Court rulings are considered leading cases regarding the disclosure of information generated during the deliberation and study phases of public works projects. Another relevant Supreme Court decision (June 29, 2004) ordered the disclosure of an environmental impact assessment preparatory document for the Tokai Loop Expressway project, classifying it as a technical document prepared according to established guidelines and inherently intended for eventual publication.

The Evolving Landscape of Information Disclosure in Japan

The legal and societal context surrounding information disclosure in Japan has continued to evolve since the 1994 Kamo River decision. For instance, a 2010 report by a Cabinet Office "Administrative Transparency Review Team" proposed amendments to the national Act on Access to Information Held by Administrative Organs. One proposal was to delete the phrase "information that is likely to unduly cause confusion among the public" from the analogous exemption for deliberation and examination information (Article 5, item 5 of the national Act), citing concerns that such wording is excessively vague and susceptible to arbitrary interpretation by administrative agencies.

Statistics show a significant increase in information disclosure requests at the national level, with requests to administrative agencies reaching a record high in FY2019. This indicates a growing public demand for transparency. Moreover, there is a broader shift in administrative style towards encouraging public participation from the early stages of planning for public projects. Achieving efficient, high-quality administration while ensuring accountability to the public remains a key contemporary challenge.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1994 decision in the Kamo River dam site map case represents an important early judicial pronouncement on the scope of information disclosure concerning internal governmental planning documents. By upholding the Kyoto Governor's decision to withhold a preliminary and "immature" map, the Court gave significant weight to the potential for "significant hindrance" to the ongoing decision-making process, particularly in light of the actual confusion and pressure that arose from earlier, limited announcements. This case, especially when viewed alongside others like the Aigawa Dam ruling, illustrates the courts' efforts to draw lines based on the nature, maturity, and source of the information in question. While a product of its time, interpreting a local ordinance before the full development of national information disclosure law and practice, the Kamo River decision highlighted key tensions and interpretative challenges that continue to be relevant in the ongoing quest to balance governmental transparency with the effective functioning of administrative deliberation.