Who Owns the Map? Copyright & Work-Made-for-Hire Rules for Residential Maps in Japan

TL;DR

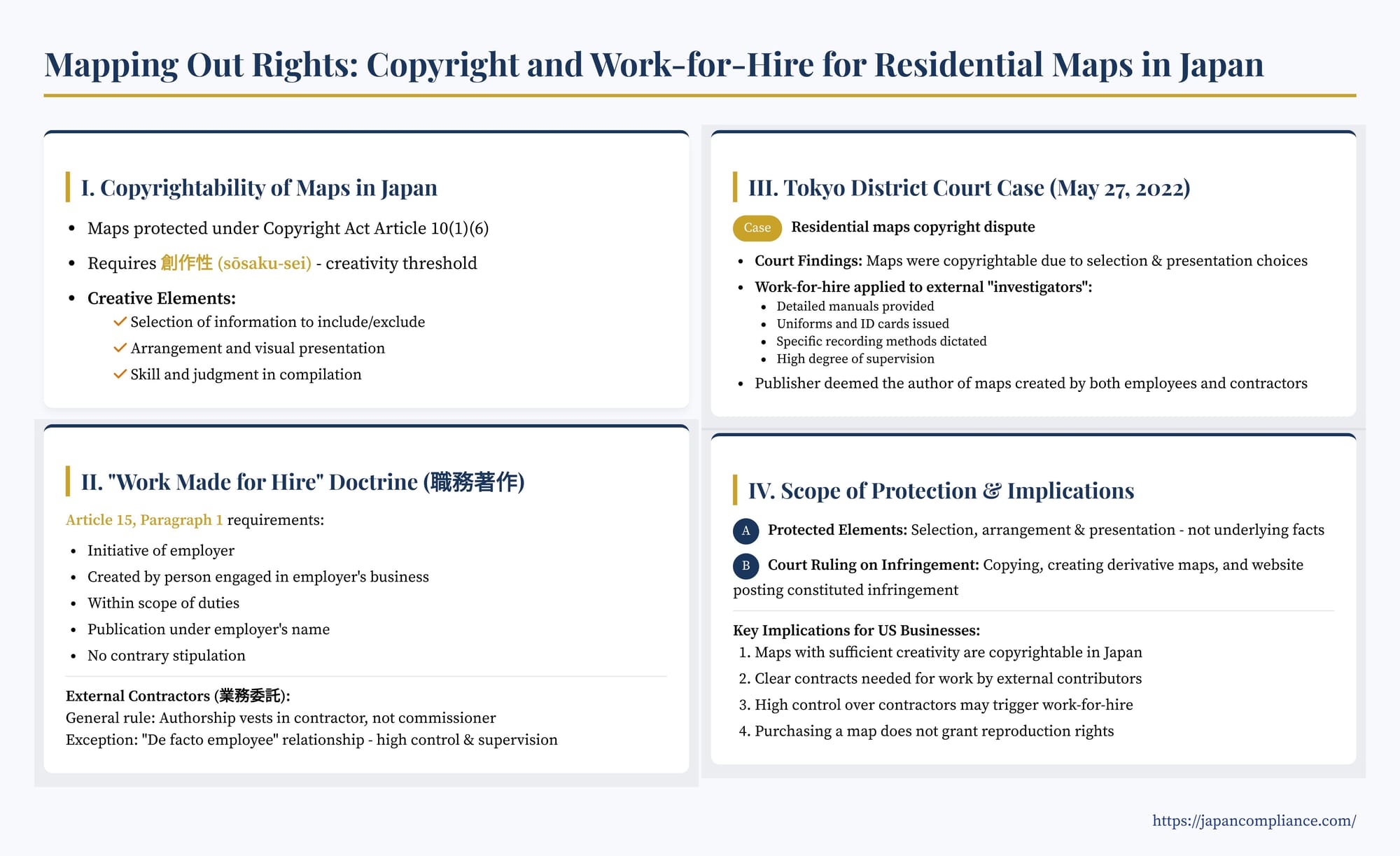

Japan’s 2022 Tokyo District Court decision confirms that detailed residential maps can be copyrighted and that, where a publisher tightly directs both employees and “quasi-employee” contractors, authorship vests in the company under Article 15. Clear contracts are still vital.

Table of Contents

- Copyrightability of Maps in Japan

- The Work-Made-for-Hire Rule (Article 15)

- Employees vs. Independent Contractors

- “De-facto employee” test

- Tokyo District Court (27 May 2022) Key Facts & Holding

- Practical Contract Tips

- Implications for U.S. Businesses

In the digital age, maps and geographical data are ubiquitous, forming the backbone of countless business services, from logistics and delivery to real estate and marketing. While often perceived as purely factual compilations, the creation of detailed maps, particularly specialized ones like residential maps (jūtaku chizu), involves significant labor, skill, and potentially, creative expression. This raises important questions about copyright protection and authorship, especially when such maps are created through complex processes involving multiple contributors, including employees and external contractors.

A Tokyo District Court judgment on May 27, 2022 (Reiwa 4), brought these issues to the forefront, affirming the copyrightability of detailed residential maps and clarifying the application of Japan's "work made for hire" doctrine in determining authorship. This case offers valuable insights for U.S. companies that create, use, or commission map-based data or similar compilations in Japan.

Copyrightability of Maps in Japan: More Than Just Facts

Under Japan's Copyright Act (Chosakken Hō), maps can be protected as "works of drawing, or works of a scientific nature such as plans, charts, models, or other diagrammatic works" (Article 10, Paragraph 1, Item 6). However, like in many jurisdictions, copyright protects the expression of information, not the underlying facts themselves. For a map to be copyrightable, it must embody "creativity" (創作性 - sōsaku-sei), meaning it must be an "expression of thoughts or sentiments in a creative way, which falls within the literary, scientific, artistic, or musical domain" (Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 1).

- Creativity in Cartography: While maps represent objective geographical realities, the threshold for creativity in this context isn't necessarily high artistic originality. Instead, it often lies in:

- Selection of Information: The cartographer makes choices about what information to include (e.g., building names, resident names, specific public facilities, road classifications, house footprint shapes – kakō-waku) and what to omit from the vast amount of available data.

- Arrangement and Presentation: The way this selected information is arranged, symbolized, and visually presented on the map also involves creative choices. This includes the use of specific symbols, colors, layout, and the overall design aimed at making the map easily searchable and understandable for its intended purpose.

- Effort and Skill: While effort (rōryoku) and cost alone do not confer copyright, the skill, experience, and judgment applied in the selection, compilation, and representation processes contribute to the creative expression.

In the Tokyo District Court case of May 27, 2022, the court recognized the copyrightability of highly detailed residential maps. It reasoned that these maps were not mere mechanical reproductions of existing data like city planning diagrams. Instead, they incorporated information gathered through extensive fieldwork by investigators (including precise building footprint shapes), historical data from previously created maps, and a specific selection and presentation of details (such as building names, resident names, and easily identifiable illustrations for facilities) tailored to the needs of users of residential maps. The court found that the map publisher's long-standing expertise and choices in what information to include and how to display it constituted a creative expression, making the maps eligible for copyright protection.

This contrasts with a historical reluctance in some earlier Japanese judicial thought to readily grant copyright to utilitarian maps, which were sometimes seen as having limited scope for creative expression due to their emphasis on functionality. The 2022 decision signals a recognition that even practical, information-rich maps can embody sufficient originality in their selection and presentation.

Authorship: The "Work Made for Hire" Doctrine in Japan

Once copyrightability is established, determining the author is crucial, as the author is the initial owner of the copyright. When works are created in a corporate setting, Japan's "work made for hire" doctrine (職務著作 - shokumu chosaku), outlined in Article 15 of the Copyright Act, often comes into play.

Article 15, Paragraph 1 (General Works Made for Hire):

This provision states that the authorship of a work (other than a computer program, which has a separate provision in Paragraph 2) made by an employee of a legal person (e.g., a company) or other employer, in the course of their duties and at the initiative of that employer, is attributed to the employer as author, unless otherwise stipulated in a contract, work rules, or the like at the time of creation. A further condition is that the work must be made public under the name of the employer as author (or if not made public, the work is attributed to the employer if it would have been made public under its name).

The key requirements are:

- Initiative of the Employer: The creation of the work must be initiated or commissioned by the employer.

- By a Person Engaged in the Business of the Employer (Employee): The work must be created by someone "engaged in the business" of the employer. This clearly includes direct employees.

- In the Course of Duties: The creation must fall within the scope of the employee's job responsibilities.

- Publication Under the Employer's Name (or intent to do so): The work is made public under the employer's name, or if unpublished, the circumstances suggest it would have been.

- No Contrary Stipulation: There must be no contract, work rules, or other agreement at the time of creation stating that the individual creator retains authorship.

Application to Works by External Contractors (業務委託 - gyōmu itaku):

The application of the work-made-for-hire doctrine becomes more nuanced when individuals who are not direct employees, such as external contractors or commissioned parties (persons under a gyōmu itaku keiyaku – service entrustment agreement, or ukeoi keiyaku – contract for work), are involved in the creation process.

- General Rule for Contractors: As a general principle, if a work is created by an independent contractor, authorship (and initial copyright ownership) vests in the individual contractor, not the commissioning party, unless there is a specific contractual agreement transferring the copyright to the commissioner. The work-made-for-hire doctrine under Article 15 typically does not automatically apply to true independent contractors because they are not "persons engaged in the business of the employer" in the same way as employees.

- The "De Facto Employee" Consideration: However, Japanese courts may look at the substance of the relationship rather than just the label of the contract. If an external contractor works under conditions that closely resemble an employment relationship – for example, working under the direct and detailed supervision and control of the commissioning company, using the company's equipment and facilities, and having little independent discretion – there's a possibility they could be deemed a "person engaged in the business of the employer" for the purposes of Article 15.

- The Supreme Court decision in the RGB Adventure case (April 11, 2003, Minshu Vol. 57, No. 4, p. 469) indicated that when employment status is disputed, whether someone is a "person engaged in the business of a legal person, etc." under Article 15(1) should be determined by comprehensively considering factors like the actual mode of work, the presence of direction and supervision, and whether payments are remuneration for labor, to see if there is a substantive employer-employee-like relationship. Subsequent lower court decisions have often followed this substantive approach.

The Tokyo District Court (May 27, 2022) on Contractors and Work-for-Hire:

In the residential map copyright case, the map publisher (Plaintiff X) used both its own employees and external contractors ("investigators" - chōsain) to gather data and create the maps. The defendants argued that Plaintiff X could not claim authorship for portions created by these external investigators.

The court, however, found that the work-made-for-hire doctrine did apply, attributing authorship to Plaintiff X even for the contributions of the external investigators. The court's reasoning was based on the high degree of control and supervision Plaintiff X exercised over these investigators:

- Plaintiff X provided detailed investigation manuals to the contractors.

- Contractors were required to wear uniforms supplied by Plaintiff X and carry identification cards issued by Plaintiff X.

- Plaintiff X dictated specific methods for recording information (addresses, names, terrain, building types, etc.) onto survey manuscripts.

- The investigation methods used by external contractors were not different from those used by Plaintiff X's direct employees performing similar tasks.

Based on these factors, the court concluded that the investigations and the recording of results onto the maps by both employees and external contractors were performed "under the direction and supervision of Plaintiff X, as part of the execution of duties for Plaintiff X." Since Plaintiff X also published the maps under its own name, the conditions for work-made-for-hire under Article 15, Paragraph 1 were met, and Plaintiff X was deemed the author.

This aspect of the ruling is significant because it extends the "work made for hire" principle to individuals who might be formally classified as external contractors, provided the commissioning company exercises a degree of control and supervision akin to that over employees. This underscores the importance for companies to clearly define relationships and intellectual property ownership in their contracts with any external parties involved in creative work. The court, in this instance, did not heavily weigh the "remuneration for labor" aspect that was also mentioned in the RGB Adventure Supreme Court case when considering external contractors, focusing more on the element of direction and supervision.

It is also important to note a potential interaction with Japan's Subcontract Act (Shitauke Hō – Act against Delay in Payment of Subcontract Proceeds, Etc. to Subcontractors). While Article 15 of the Copyright Act itself states that work-for-hire applies "unless otherwise stipulated," the Subcontract Act requires that when a parent事業者 (oya jigyōsha - principal entrepreneur) commissions information-based deliverables (like software or content) from a下請事業者 (shitauke jigyōsha - subcontractor), the written order (the "Article 3 document") must clearly state the scope of any transfer or license of intellectual property rights. This means that relying solely on the default work-for-hire rule without clear contractual language might be insufficient or problematic under the Subcontract Act.

Scope of Copyright Protection for Maps

The Tokyo District Court decision also implicitly touches upon the scope of copyright protection for maps. While the underlying geographical facts (location of roads, buildings, etc.) are not copyrightable, the creative expression in the selection, arrangement, and presentation of these facts is.

In the case, the defendant company had purchased the plaintiff's residential maps, made reduced photocopies, cut and pasted portions to create their own delivery route maps, and added their own information (e.g., apartment building names, number of mailboxes). These derivative maps were then photocopied and distributed to delivery staff. The defendant also posted images of these derivative maps on its website.

The court found these actions (copying, creating derivative maps for distribution, and public transmission via the website) to constitute copyright infringement (infringement of the rights of reproduction, transfer, and public transmission). This indicates that even if a user adds their own information to a copyrighted map, the unauthorized reproduction and adaptation of the copyrighted base map's creative elements can still lead to infringement.

The defendants had argued that their use of the maps was not for the purpose of enjoying the thoughts or sentiments expressed therein (a potential defense under Article 30-4 of the Copyright Act concerning reproduction incidental to data analysis). However, the court rejected this, finding that the defendants were indeed using the information contained in the maps (such as building locations and roads) for their business, and this involved reproducing the plaintiff's copyrighted expression.

Implications for U.S. Businesses

The May 27, 2022, Tokyo District Court decision offers several important takeaways for U.S. companies:

- Detailed Maps Can Be Copyrightable: Do not assume that maps or map-like databases are devoid of copyright protection in Japan simply because they contain factual information. Sufficient creativity in the selection, arrangement, and presentation of data can lead to copyrightable works. This is particularly relevant for companies involved in GIS, logistics, real estate, or any field that relies on customized or value-added mapping.

- "Work Made for Hire" Requires Careful Management:

- For works created by direct employees within the scope of their duties and at the company's initiative, authorship will generally vest in the company if published under its name and there's no contrary agreement.

- For works created by external contractors, freelancers, or commissioned parties, authorship (and initial copyright) presumptively belongs to the individual creator. To secure rights, companies must have clear contractual agreements in place that explicitly transfer copyright ownership to the commissioning company.

- However, as the 2022 case illustrates, if a company exercises significant direction and supervision over external contractors, making the relationship substantively similar to that with an employee regarding the specific work creation, a Japanese court might still apply the work-made-for-hire doctrine in favor of the commissioning company, even without an explicit copyright transfer clause for those specific deliverables (though having one is always best practice). The level of control is a key factual determination.

- Contracts are Key: Regardless of the default rules, clear contractual provisions are essential to define IP ownership, usage rights, and authorship for any creative work, whether developed internally, by employees, or by external parties. This includes specifying how IP developed by contractors will be handled and ensuring that any necessary rights are assigned to the company. For プログラムの著作物 (puroguramu no chosakubutsu - program works, i.e., software), Article 15, Paragraph 2 has a slightly different work-for-hire rule that more readily attributes authorship to the employer unless otherwise specified, without the "publication under employer's name" requirement.

- Scope of Permissible Use: Purchasing a copyrighted map or database does not automatically grant the right to reproduce, adapt, or publicly distribute it, even for internal business purposes that go beyond mere viewing. Licenses for such uses must be obtained, or companies risk infringement claims. Modifying and repurposing copyrighted map data for internal operational tools, as the defendant did, can still be infringing if it involves reproducing the copyrighted expression of the original map.

As businesses increasingly rely on sophisticated geographical information and data compilations, understanding the nuances of Japanese copyright law, particularly concerning the originality of such works and the rules governing authorship in corporate and contractual settings, is vital for protecting investments and avoiding costly legal disputes. The 2022 Tokyo District Court decision serves as a reminder that even seemingly utilitarian works like residential maps can be valuable copyrighted assets demanding careful legal consideration.