Manpower vs. Woman Power: Japan's Supreme Court on Business Name Similarity and Broad-Sense Confusion

Judgment Date: October 7, 1983

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Case Number: Showa 57 (O) No. 658 (Claim for Injunction Against Use of Trade Name, etc.)

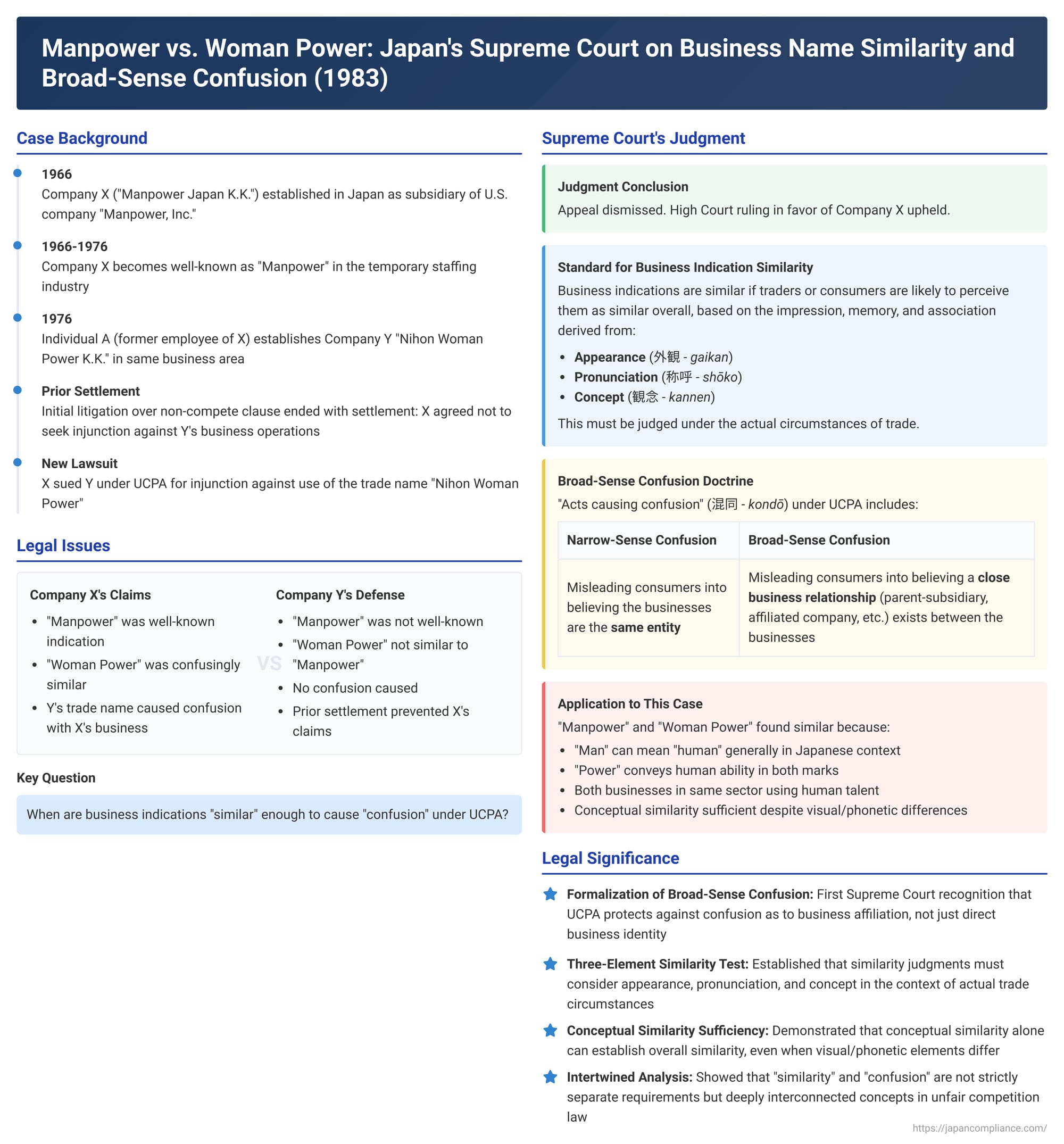

The "Nippon Woman Power" case (日本ウーマン・パワー事件), decided by the Japanese Supreme Court in 1983, is a significant judgment in the field of unfair competition law. It provided crucial clarifications on two key aspects: first, the criteria for determining when business indications (such as trade names or common names) are "similar" enough to cause issues; and second, the scope of "acts causing confusion," explicitly affirming that this includes not only direct misidentification of business entities but also broader "broad-sense confusion" where consumers might mistakenly believe an affiliation or other close relationship exists between businesses. This ruling has had a lasting impact on how well-known business identifiers are protected in Japan.

The Business Background: Staffing Services and a Spin-Off

The dispute arose in the burgeoning business services sector, specifically temporary staffing and office work contracting.

- Company X (Plaintiff/Appellee): Company X, legally "Manpower Japan Kabushiki Kaisha," was established in Japan in 1966. It was a subsidiary of the globally renowned U.S. corporation "Manpower, Inc.," a pioneer and world leader in the temporary staffing industry. Company X operated under its formal trade name and, significantly, was also widely known by its common name or通称 (tsūshō), "Manpower". It provided a range of office support services, including dispatching interpreters, translators, typists, secretaries, and various other skilled office personnel to client companies.

- Company Y (Defendant/Appellant): Company Y, legally "Nihon Woman Power Kabushiki Kaisha" (Nippon Woman Power Inc.), was established in April 1976 by Individual A. Individual A was a former employee of Company X. Company Y entered the same line of business as Company X – providing temporary staffing and office processing services.

- Prior Litigation and Settlement: Before the present lawsuit, Company X had initiated legal action (a request for a provisional disposition) against Company Y and Individual A, alleging a breach of a non-compete clause in A's employment contract with X, which prohibited competitive activities for two years post-resignation. This earlier dispute concluded with a court-mediated settlement. Under the terms of this settlement, Company Y and Individual A offered an apology to Company X, and, in return, Company X agreed not to seek an injunction against Company Y's business operations themselves.

The Legal Claims and Lower Court Findings

Subsequently, Company X filed the instant lawsuit against Company Y. This time, the claim was not based on the non-compete clause but on Japan's (then-effective) Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA). Company X argued that Company Y's use of its trade name "Nihon Woman Power Kabushiki Kaisha" constituted an act of unfair competition under Article 1, Paragraph 1, Item 2 of the old UCPA. This provision (broadly equivalent to Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the current UCPA) prohibited the use of a business indication identical or similar to another person's well-known business indication in a manner that causes confusion with that other person's business. Company X sought an injunction to prevent Company Y from using its trade name and also requested the cancellation of Y's trade name from the commercial register.

Company Y raised several defenses:

- It argued that Company X's trade name ("Manpower Japan Kabushiki Kaisha") and its common name ("Manpower") were not, in fact, "well-known" (周知 - shūchi) as required by the UCPA.

- It contended that the use of its trade name ("Nihon Woman Power Kabushiki Kaisha") did not cause any misidentification or confusion with Company X's business.

- It invoked the prior court settlement, arguing that Company X, having agreed not to enjoin Y's business operations, was now acting in breach of the principle of good faith and fair dealing (信義誠実の原則 - shingi seijitsu no gensoku) by bringing this new lawsuit targeting Y's trade name.

Lower Court Rulings:

Both the first instance court and the appellate High Court ruled substantially in favor of Company X.

- Well-Knownness of X's Indications: The courts found that, by the time Company Y was established in 1976, Company X's trade name and, particularly, its common name "Manpower" had achieved well-known status. This was based on evidence of Company X's expanding business operations, its growing scale, and its advertising expenditures.

- Similarity of Indications and Likelihood of Confusion: The courts also found that Company Y's trade name was confusingly similar to Company X's indication "Manpower." While acknowledging the visual and phonetic differences between "Man" and "Woman," the first instance court noted that these words are antonyms, which can create a conceptual link. It also considered evidence of actual instances where confusion had occurred. Consequently, the courts affirmed the likelihood of misidentification or confusion.

- Estoppel Defense Rejected: The courts rejected Company Y's defense based on the prior settlement. They interpreted the settlement as Company X only relinquishing its right to seek an injunction against Company Y's business activities in general (based on the non-compete claim). It did not, in their view, constitute a waiver of X's separate right to seek an injunction against the specific use of Y's trade name if that use constituted an act of unfair competition.

Company Y appealed these findings to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Rulings

The Supreme Court dismissed Company Y's appeal, thereby upholding the lower courts' decisions in favor of Company X. The Supreme Court's judgment provided crucial clarifications on the standards for assessing the similarity of business indications and the scope of actionable confusion under the UCPA.

I. On the Similarity of Business Indications (類似性 - ruijisei)

The Court laid down a general standard for determining whether one business indication is "similar" to another for the purposes of the UCPA:

"In judging whether a certain business indication is similar to another person's business indication as per [old UCPA] Article 1, Paragraph 1, Item 2, it is appropriate to use as a standard whether, under the actual circumstances of trade, traders or consumers are likely to perceive both indications as similar overall, based on the impression, memory, association, etc., derived from their appearance (外観 - gaikan), pronunciation (称呼 - shōko), or concept (観念 - kannen)."

Applying this standard to the specific facts:

- The Court identified the essential part (要部 - yōbu) of Company X's business indication as its well-known common name "Manpower". The essential part of Company Y's trade name was "Woman Power".

- While acknowledging the difference between "Man" and "Woman," the Court considered the contemporary understanding of English in Japan:

- The word "Man" is not only known to mean male but can also refer to "human" generally, thus capable of encompassing "woman".

- The word "Power" is understood to mean not just physical strength but also human ability, talent, or intellectual capacity.

- The Court noted the context of their businesses: both Company X and Company Y were headquartered in Tokyo and engaged in the same business of temporary staffing and office services, a field that inherently utilizes human abilities and intellect. Their customer bases were also common.

- Conclusion on Similarity: Given these factors, the Supreme Court concluded that, for their shared customer base, both "Manpower" and "Woman Power" would likely evoke the concept of human ability or intellectual resources. They were therefore likely to be perceived as conceptually similar. Additionally, the "Japan" part of X's formal trade name and the "Nihon" (Japan) part of Y's trade name are identical in meaning, further contributing to potential overlap. Consequently, the Court found that Company X's business indication ("Manpower") and Company Y's trade name ("Nihon Woman Power") were likely to be perceived by the relevant consumers as similar overall. The High Court's finding of similarity was thus affirmed as justifiable.

II. On "Acts Causing Confusion" (混同 - kondō) – Endorsement of Broad-Sense Confusion

This was a particularly significant part of the judgment. The Supreme Court explicitly defined the scope of "acts causing confusion":

"The phrase 'acts that cause confusion' in [old UCPA] Article 1, Paragraph 1, Item 2 includes not only acts whereby a person using an identical or similar indication to another's well-known business indication misleads others into believing that they and the said other person are the same business entity (this is often referred to as 'narrow-sense confusion')."

"It also includes acts that mislead others into believing that a close business relationship, such as that of a parent company and subsidiary, or an affiliated company relationship (系列関係 - keiretsu kankei), etc., exists between the two entities." This is the doctrine of "broad-sense confusion" (広義の混同 - kōgi no kondō).

Applying this to the facts, the Supreme Court stated:

"In the present case,... Company Y, by using a business indication similar to Company X's well-known business indication, committed acts that either misled others into believing that Company Y and Company X were the same business entity OR that a close business relationship existed between them. Ultimately, it can be said that Company Y committed acts that caused confusion with Company X's business activities."

The High Court's finding to this effect was also deemed justifiable.

Understanding the Significance: Broad-Sense Confusion and Intertwined Requirements

The Nippon Woman Power case is a cornerstone in Japanese unfair competition law for several reasons:

- Formal Endorsement of "Broad-Sense Confusion": While the precise scope of "confusion" was not the most fiercely contested point in this specific appeal, the Supreme Court's clear and explicit articulation that "acts causing confusion" under the UCPA include broad-sense confusion (mistaken belief of affiliation, sponsorship, etc.) was highly significant. It provided strong precedential authority for a broader interpretation of actionable confusion, which had been developing in lower courts. This stance was subsequently reaffirmed by the Supreme Court in later cases under both the old and current UCPA (e.g., the Football Symbol Mark case and the Snack Chanel case ). This recognizes the complex ways consumers can be misled in modern markets where corporate groups, licensing, and other affiliations are common.

- The Interplay of "Similarity" and "Confusion": The UCPA, like many intellectual property statutes, lists "similarity" of indications and "causing confusion" as if they are distinct requirements for establishing a claim. However, the PDF commentary accompanying the Nippon Woman Power case suggests that the Supreme Court's approach, here and in trademark law generally, often treats these concepts as deeply intertwined rather than as entirely separate hurdles.

- The Court's method for judging "similarity"—a holistic assessment of appearance, pronunciation, and concept, viewed through the prism of actual trade circumstances and how consumers perceive the marks—is, in effect, very close to determining whether a likelihood of confusion exists. If indications are deemed similar under this comprehensive test, it's often because they are similar in a way that is likely to lead to source confusion.

- The commentary argues that this pragmatic approach allows the Supreme Court to achieve a degree of consistency in regulatory philosophy across different intellectual property laws (UCPA, the old Commercial Code provisions on trade names, and the Trademark Law), all of which, in their own ways, aim to protect source identifiers and prevent misattribution in the marketplace.

- For instance, if "similarity" were judged solely on the literal, physical attributes of the marks "Manpower" and "Woman Power" in isolation, one might conclude they are dissimilar due to the clear visual and phonetic differences between "Man" and "Woman." However, by factoring in the conceptual link (as antonyms, yet both pertaining to human capability in the context of staffing services) and the realities of their shared business sector and customer base, the Court found a similarity that was pertinent to the likelihood of source confusion.

- Critique of Strictly Separating "Similarity" and "Confusion": The PDF commentary raises a thoughtful critique: Is it truly useful to treat "similarity" and "confusion" as entirely distinct legal requirements? If business indications are so different that no reasonable consumer could be confused, then the UCPA's protection isn't triggered. Conversely, if they are similar enough to create a realistic potential for confusion, then the analysis of "similarity" itself inherently incorporates considerations of how consumers perceive these indications and how they might be misled. The very assessment of an indication's characteristics (appearance, sound, meaning) is inevitably done from the consumer's viewpoint concerning its capacity to function as a clue to identify a particular business entity.

Conclusion

The Nippon Woman Power Supreme Court judgment stands as a vital precedent in Japanese unfair competition law. It solidified the framework for assessing the similarity of business names and other commercial indications by mandating a holistic, context-sensitive approach that considers appearance, pronunciation, concept, and actual trade realities. Even more crucially, it unequivocally affirmed that the "confusion" prohibited by the UCPA is not limited to consumers mistaking one business for another entirely (narrow-sense confusion) but also extends to "broad-sense confusion," where consumers are misled into believing a non-existent affiliation or other close commercial relationship exists between the parties. This ruling provided more robust protection for established businesses against a wider range of deceptive practices and has significantly shaped the interpretation and application of unfair competition principles in Japan, ensuring that the law remains responsive to the complexities of modern commercial branding and corporate structures.