Manipulating Creditor Votes in Civil Rehabilitation: Supreme Court Defines "Improper Means"

Date of Decision: March 13, 2008 (Heisei 20)

Case Name: Permitted Appeal Against Appellate Decision Annulling Rehabilitation Plan Confirmation

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

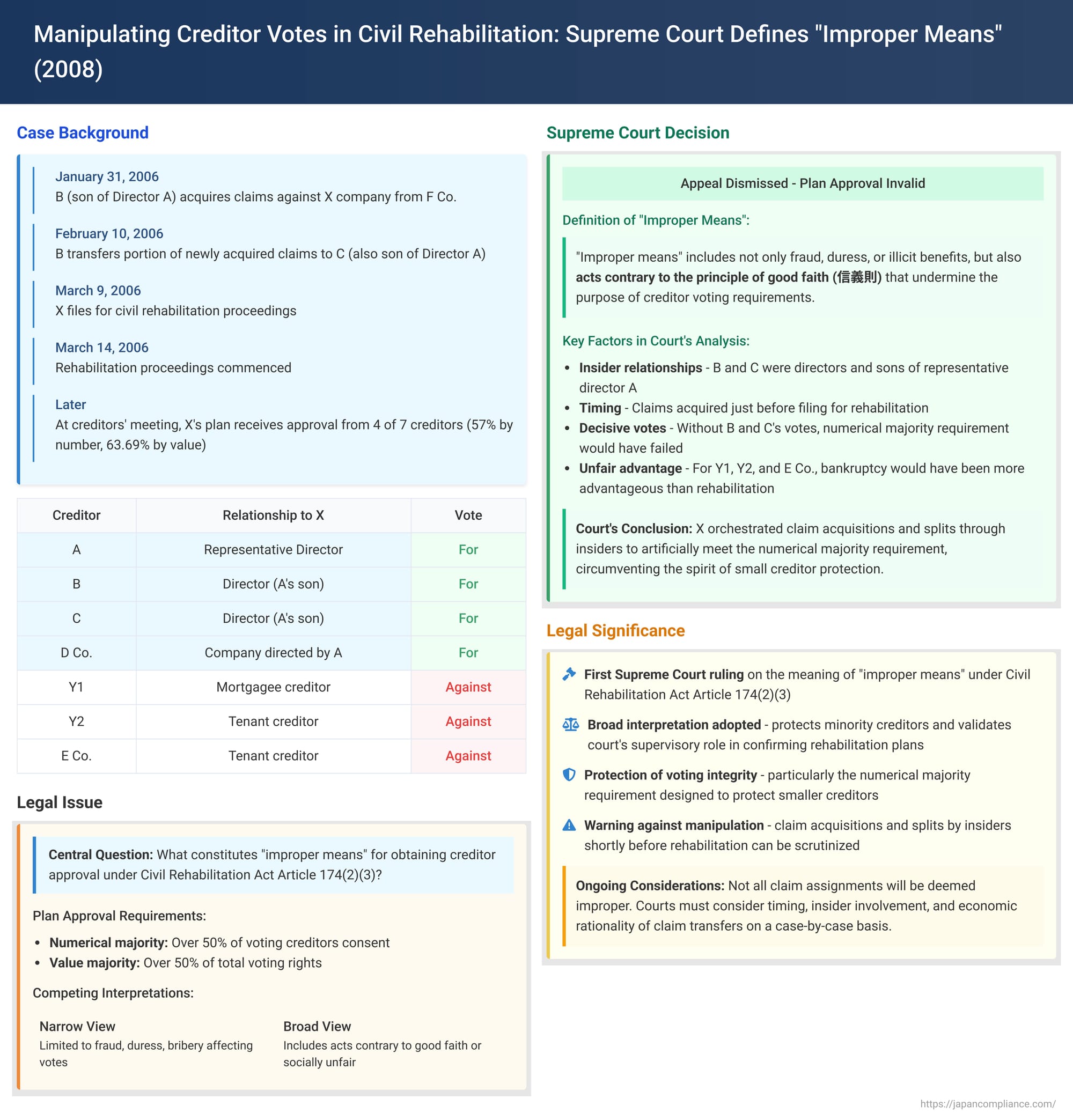

This blog post examines a 2008 Supreme Court of Japan decision that addressed a critical issue in corporate civil rehabilitation proceedings: what constitutes "improper means" for obtaining creditor approval of a rehabilitation plan? The case specifically involved allegations that a debtor company, through its insiders, orchestrated claim assignments just before filing for rehabilitation to artificially satisfy the voting requirements for plan approval.

Facts of the Case

The debtor, X (appellant before the Supreme Court), was a real estate leasing company whose representative director was A. X's primary asset was a commercial building. X had borrowed a total of 800 million yen, for which mortgages were established on this building. Due to failures in stock investments and other factors, X's business collapsed, and foreclosure on the building by the mortgagees became inevitable.

B and C, sons of A and also directors of X, initially held no claims against X. However, on January 31, 2006, B acquired claims against X from a third party, F Co., knowing these claims were likely uncollectible. On February 10, 2006, B transferred a portion of these newly acquired claims to C.

On March 9, 2006, X filed for commencement of civil rehabilitation proceedings with the Tokyo District Court, and proceedings were initiated on March 14. On March 31, X applied for and received permission from the rehabilitation court to extinguish the existing mortgages on its building, arguing the building was indispensable for business continuation. (The decision text details a more complex original mortgage structure involving H and I, with Y1 eventually acquiring these mortgage rights, and G providing new financing for X to pay off the extinguished security interest's value ).

X submitted a rehabilitation plan. At the creditors' meeting, all seven of X's registered rehabilitation creditors attended. The plan was approved by four creditors: A (X's representative director), B (A's son and X's director), C (A's son and X's director), and D Co. (a company whose representative director was also A). These four represented a majority in the number of voting creditors and held 63.69% of the total amount of voting rights. (The decision text notes that D, E, A, and company C voted for the plan. For consistency with the anonymization key derived from the PDF facts summary and the decision's focus on B and C (D and E in decision text) acquiring claims, we'll refer to the voting sons as B and C).

It was noted that if X were to go into bankruptcy, no distribution to creditors was anticipated. However, for Y1 (the principal mortgagee creditor, an opponent of the plan) and Y2 (a tenant with a security deposit claim, also opposing), X's bankruptcy would have been more advantageous. In bankruptcy, Y1 could have potentially recovered more through an orderly sale of the building combined with other collateral, rather than the value assigned under the rehabilitation plan's security interest extinguishment. For Y2 (and another tenant, E Co.), bankruptcy would have allowed a broader scope for setting off their security deposit claims against rent obligations owed to X.

The rehabilitation court (court of first instance's first instance) initially approved the plan, finding no grounds for non-approval. However, the High Court (original instance court for the appeal against plan approval) reversed this decision, finding that the plan approval was tainted by grounds for non-approval under Article 174, Paragraph 2, Items 3 (resolution obtained by improper means) and 4 (plan contrary to the general interests of creditors) of the Civil Rehabilitation Act. X then filed a permitted appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision not to approve the rehabilitation plan .

The Court's reasoning focused on Article 174, Paragraph 2, Item 3 of the Civil Rehabilitation Act ("when the resolution on the rehabilitation plan has been effected by improper means"):

- Purpose of Court Confirmation of Rehabilitation Plans:

The Court explained that the requirement for court confirmation, even after a plan is approved by creditors, is to allow the rehabilitation court to re-examine whether the plan is suitable for achieving the Act's objectives (as stated in Article 1: appropriate adjustment of civil legal relations between the debtor and creditors, thereby aiming to rehabilitate the debtor's business or economic life). This judicial review serves a supervisory function, protecting minority creditors and, by extension, the general interests of all rehabilitation creditors. - Interpretation of "Improper Means":

Given this purpose, the phrase "when the resolution on the rehabilitation plan has been effected by improper means" under Article 174(2)(iii) is not limited to situations where voting rehabilitation creditors were subjected to fraud, duress, or the provision of illicit benefits. It also includes cases where the approval of the rehabilitation plan was achieved through acts contrary to the principle of good faith (信義則 - shingi-soku). The Court referenced Article 38, Paragraph 2 of the Act (which imposes a duty of fairness and good faith on the rehabilitation debtor) in support of this broader interpretation. - Application to the Facts of the Case:

The Supreme Court highlighted the following factual circumstances:- For certain creditors of X (namely Y1, Y2, and E Co.), X undergoing civil rehabilitation was less favorable for their debt recovery than if X were to go through bankruptcy proceedings. It was anticipated that if X filed for rehabilitation and submitted the plan, it would only secure the consent of A (X's representative director) and D Co. (the company A also represented), and thus the plan would not be approved due to failing the numerical majority requirement.

- Just before X filed for rehabilitation, B (a director of X and son of A, who previously held no claims against X) acquired a likely uncollectible claim against X (the decision text details this as F Co.'s claim against company C, which X had guaranteed, being acquired by D – who corresponds to B in the summary – and then D assigned part of this guarantee claim against X to E – who corresponds to C in the summary).

- B and C then registered these acquired claims as rehabilitation claims and exercised their voting rights in favor of X's rehabilitation plan.

- It was clear that without B's and C's affirmative votes, the requirement for approval by a majority in number of voting creditors (as per Article 172-3, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Act) would not have been satisfied. Their votes were decisive in meeting this "numerical majority" or "head-count" requirement and securing the plan's passage.

- Conclusion on "Improper Means":

The Supreme Court concluded that the rehabilitation plan was approved, despite an initial expectation that it would fail to secure the necessary majority in number, because B and C (directors of X) acquired and split a likely worthless claim, thereby creating a situation where four parties closely related to X (A, B, C, and D Co.) constituted a numerical majority of the voting creditors. This series of actions, orchestrated by X's insiders, was deemed to be a circumvention of the spirit of creditor protection (particularly small creditor protection) embodied in the numerical majority requirement of Article 172-3(1)(i), and thus constituted an act contrary to the principle of good faith by X and its affiliates. Therefore, the resolution approving the plan was held to have been effected by "improper means". The High Court's similar finding was affirmed .

Commentary and Elaboration

1. Background: Voting Requirements in Civil Rehabilitation

For a rehabilitation plan to be approved by creditors in Japan, it must satisfy two primary voting thresholds (Civil Rehabilitation Act Article 172-3, Paragraph 1):

- Majority in Number: Consent from a majority of the rehabilitation creditors who exercise their voting rights.

- Majority in Value: Consent from creditors holding more than one-half of the total amount of voting rights of all creditors entitled to vote.

This case centered on the manipulation of the "majority in number" requirement (often referred to as 頭数要件 - kazuatari yōken or atama-kazu yōken).

2. Academic Discussion on "Improper Means"

Article 174, Paragraph 2, Item 3 of the Civil Rehabilitation Act, which allows the court to refuse confirmation of a plan if its approval was achieved by "improper means," was inherited from similar provisions in older Japanese insolvency statutes (e.g., the Composition Act and the old Corporate Reorganization Act). Under the old Composition Act, "improper means" was generally understood to encompass actions like fraud, bribery, or duress affecting creditors' votes, or voting by fictitious creditors. A narrow interpretation, limiting it only to undue influence by third parties on the voting process, was not generally adopted. Even under the Civil Rehabilitation Act prior to this Supreme Court decision, legal commentators generally favored a broad interpretation of "improper means," considering it to include any act contrary to good faith or acts deemed unfair by societal standards.

3. Significance of the Supreme Court's Decision

- This was the Supreme Court's first interpretation of "improper means" under Article 174(2)(iii) of the Civil Rehabilitation Act.

- The Court explicitly adopted a broad interpretation, stating that "improper means" includes not only clear-cut illicit acts like fraud or bribery but also extends to "acts contrary to the principle of good faith" (shingi-soku). This aligns with the established practical approach and prevailing academic views. (The commentary notes that the High Court had used the phrase "unfair means not condoned by law," which the Supreme Court rephrased as "acts contrary to good faith").

- Notably, the Supreme Court did not address the High Court's additional finding that the plan was also non-approvable under Article 174(2)(iv) (i.e., being contrary to the general interests of creditors).

4. Rationale for the Broad Interpretation

The Supreme Court justified its broad interpretation by referring to the purpose of requiring court confirmation of an already creditor-approved plan: it allows the court, from a supervisory (or "guardian-like") perspective, to protect minority creditors and thereby ensure the protection of the general interests of all rehabilitation creditors. The numerical majority requirement itself is understood to be a mechanism for protecting small-value creditors. Therefore, actions designed to circumvent this requirement were seen by the Court as undermining this protective purpose and thus constituted "improper means". (The decision does not, however, delve into a deeper explanation of why such protection for minority/small creditors is necessary or how it specifically serves the general interest of all creditors).

5. Factors in the Supreme Court's Factual Assessment

In applying its interpretation to the facts, the Supreme Court emphasized:

- That B and C were insiders of the debtor company X (being directors and sons of the representative director A).

- The causal link between the claim assignments to B and C and the satisfaction of the numerical majority requirement for plan approval; without their votes, the plan would have failed this threshold.

- The Court did not explicitly discuss the subjective intent of A, B, or C (e.g., a specific intent to circumvent the voting requirements), focusing instead on the objective nature and effect of their actions.

- The reference to Article 38, Paragraph 2 of the Act (debtor's duty of fairness and good faith) in the Court's reasoning likely reflects the involvement of these insiders in the manipulative claim transfers. The finding was specifically a breach of good faith by "the rehabilitation debtor X and its affiliates".

6. Scope of "Improper Means" Post-Decision

This decision confirms a broad understanding of "improper means." The commentary suggests a possible typology of such acts, including:

- Influencing a voter to vote against their true intentions or preventing them from voting.

- Artificially increasing the number of creditors by unjustifiably splitting claims (as seen in this case).

- A creditor improperly inflating their own claim amount or voting power (e.g., by acquiring worthless claims to boost voting share).

- A creditor forging documents to substantiate inflated claims.

This case primarily involved the second type, with elements of the third, orchestrated by insiders.

7. Future Issues for Consideration

While this case presented a relatively clear-cut scenario of vote manipulation, the assignment of claims is generally a legitimate commercial activity, often used as a means of investment recovery. Therefore, not every instance of claim splitting or assignment leading to a shift in voting majorities will automatically constitute "improper means". Future cases will need to carefully consider factors such as:

- The time gap between the claim assignment and the filing of the rehabilitation petition.

- The degree of involvement of the debtor or its insiders in the claim assignment process.

- The economic rationality (or lack thereof) behind the claim assignment.

A nuanced, fact-specific analysis will be required in subsequent cases to determine where the line is drawn.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2008 decision serves as a significant warning against attempts to manipulate creditor voting in civil rehabilitation proceedings. By broadly defining "improper means" for plan approval to include bad faith actions by debtors or their insiders aimed at artificially satisfying voting thresholds, the Court has reinforced the integrity of the rehabilitation process. This ruling underscores the importance of genuine creditor consent and the court's role in safeguarding the rights of all creditors, particularly minority and small-value creditors, from collusive or manipulative practices designed to circumvent statutory protections.