Mandatory Inheritance Registration in Japan: What US Companies & Expatriates Need to Know

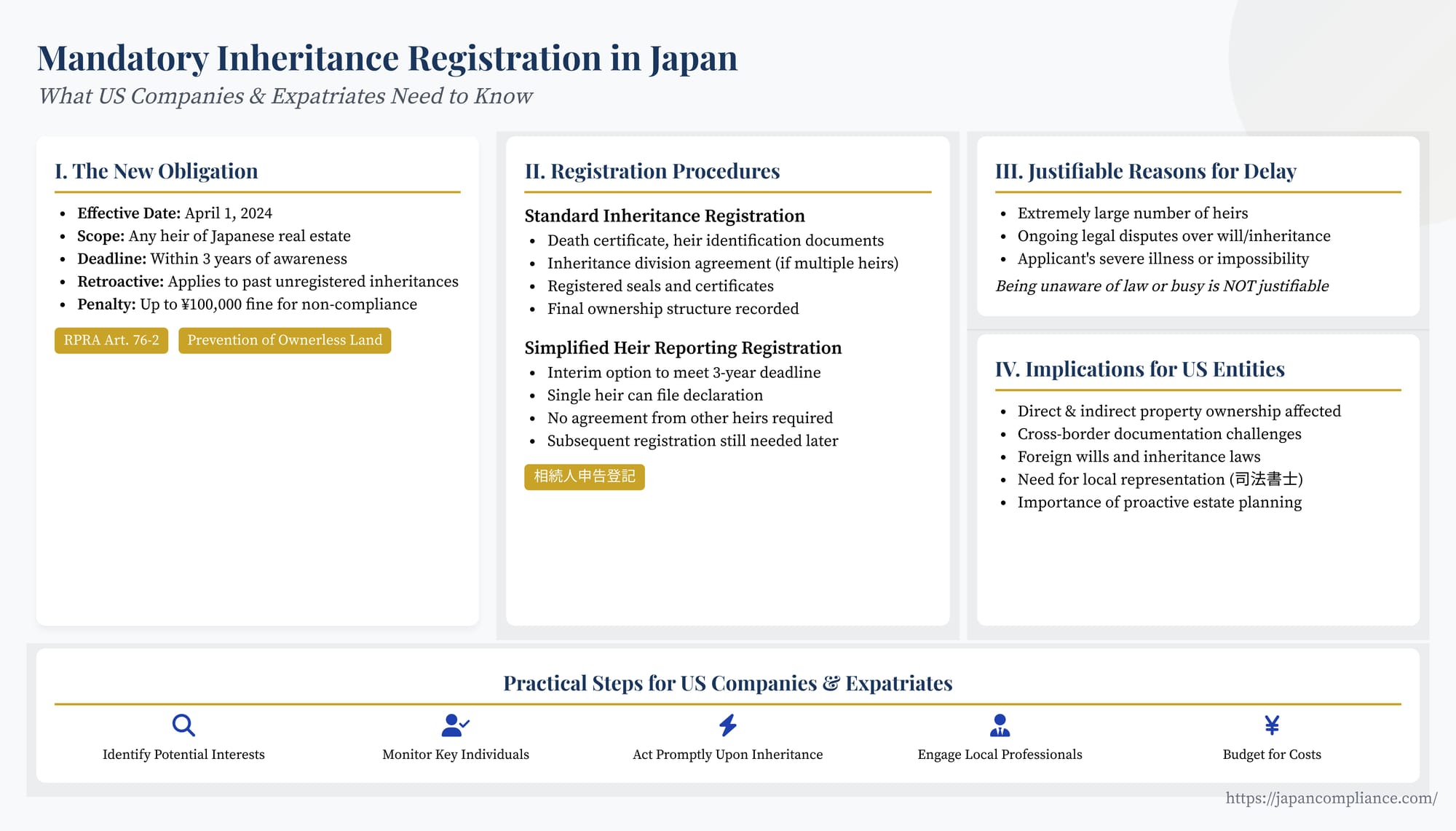

TL;DR: From 1 April 2024, heirs of Japanese real estate must register ownership within three years or face fines. A simplified “heir-reporting” option buys time, but final registration is still required. US companies and expatriates should prepare cross-border documents early and engage local counsel to avoid penalties and title problems.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: A Fundamental Shift in Japanese Real Property Law

- The New Obligation: What Changed on April 1, 2024?

- Rationale: Preventing Future “Ownerless Land”

- Understanding the Registration Procedures

- What Counts as a “Justifiable Reason” for Delay?

- Implications for US Companies and Expatriates

- Practical Steps and Considerations

- Conclusion: Compliance is Key

Introduction: A Fundamental Shift in Japanese Real Property Law

Japan's struggle with "land of unknown ownership" (shoyūsha fumei tochi)—parcels where the legal owner cannot be easily identified due to outdated or missing registry information, often stemming from unrecorded inheritances—has prompted significant legal reforms. As detailed previously, this issue hinders economic activity, redevelopment, and effective land management. A cornerstone of the government's response is the nationwide implementation of mandatory inheritance registration for real estate, a significant departure from the previous optional system.

Effective from April 1, 2024, this new requirement under the amended Real Property Registration Act (不動産登記法 - Fudōsan Tōkihō) directly impacts anyone inheriting property in Japan, including foreign corporations and individuals. Understanding the specifics of this obligation is crucial for US companies with Japanese operations, investments, or subsidiaries holding real estate, as well as for expatriates residing in or owning property within Japan. Non-compliance can lead to penalties and complicate future property transactions.

The New Obligation: What Changed on April 1, 2024?

The central change lies in new provisions within the Real Property Registration Act (RPRA):

- The Core Duty (RPRA Art. 76-2, Para. 1): An individual or entity that acquires ownership of real estate located in Japan through inheritance (including bequests via a will) must apply for the registration of that ownership transfer within three years from the date they become aware of both (a) the commencement of the inheritance (i.e., the death of the previous owner) and (b) their acquisition of the ownership.

- Scope: This obligation applies universally to all types of real estate situated in Japan, regardless of the heir's nationality or residency. If a US company inherits property through a Japanese subsidiary, or an American citizen inherits directly, this rule applies.

- Retroactive Application (Act Supplementary Provisions Art. 5, Para. 6): Crucially, the law applies not only to inheritances occurring on or after April 1, 2024, but also to those that occurred before this date but had not yet been registered. For these past inheritances, the three-year deadline starts either on April 1, 2024, or the date the heir became aware of the inheritance and their ownership, whichever date is later. This means a vast number of previously unregistered inherited properties are now subject to this deadline.

- Penalty for Non-Compliance (RPRA Art. 164, Para. 1): Failure to meet the registration deadline without a "justifiable reason" (seitō na riyū) can result in a non-criminal administrative fine (karyō) of up to ¥100,000. While not a criminal penalty, it represents a clear enforcement mechanism intended to encourage timely registration.

Rationale: Preventing Future "Ownerless Land"

The primary driver behind mandatory registration is the prevention of future ownerless land scenarios. By requiring heirs to update the property registry within a defined timeframe, the government aims to:

- Maintain Accuracy: Ensure the real property registry reflects the current ownership status promptly.

- Prevent Accumulation: Stop the cycle where inheritances go unregistered over multiple generations, leading to an exponential increase in unidentified co-owners and making ownership tracing nearly impossible.

- Facilitate Transactions: Provide clarity and certainty for real estate transactions, development projects, and public works by making it easier to identify and contact landowners.

The increasing number of inheritance registrations observed since the law's passage suggests a growing public awareness and response to this objective.

Understanding the Registration Procedures

Heirs have two main pathways to fulfill their registration obligation:

1. Standard Inheritance Registration (遺産分割等による相続登記 - Isan Bunkatsu nado ni yoru Sōzoku Tōki)

This is the conventional method that results in the final ownership structure being recorded. It typically involves:

- Gathering Documentation: Proving the death of the previous owner (death certificate), identifying all legal heirs (family register extracts - koseki tōhon, certificates of registered matters - tōki jikō shōmeisho, etc.), and establishing the basis for the inheritance (statutory succession rules or a will).

- Inheritance Division Agreement (遺産分割協議 - Isan Bunkatsu Kyōgi): If there are multiple heirs, they usually need to agree on how the inherited property will be divided. This agreement (isan bunkatsu kyōgisho) must often be formalized with registered seals (jitsuin) and seal certificates (inkan shōmeisho) from all agreeing heirs. Alternatively, heirs can register their statutory shares as co-owners.

- Application: Submitting a formal application to the relevant Legal Affairs Bureau (法務局 - Hōmukyoku) with all required documents and payment of registration taxes.

This process can be complex and time-consuming, especially with numerous heirs, heirs residing overseas, or disputes over the inheritance.

2. Simplified Heir Reporting Registration (相続人申告登記 - Sōzokunin Shinkoku Tōki) (RPRA Art. 76-3)

Introduced as part of the 2021 reforms, this is a simplified, interim measure designed to help heirs meet the three-year deadline even if the final inheritance division is not yet complete.

- Procedure: A single heir (or multiple heirs individually) can file a declaration with the Legal Affairs Bureau stating that an inheritance has occurred and identifying themselves as an heir of the deceased registered owner. This application requires proof of the inheritance relationship (e.g., family register extracts) but does not require agreement from other heirs or details of the final property division.

- Effect: Upon successful application, the Legal Affairs Bureau registers the name and address of the reporting heir(s) in the registry, officially noting that an inheritance process is underway. Crucially, filing this report fulfills the initial three-year registration obligation under Art. 76-2.

- Limitations: This registration does not finalize the ownership transfer. It merely records that the filer is an heir. The property's legal ownership status remains based on the inheritance itself (often co-ownership by all heirs).

- Subsequent Obligation: Once the inheritance division agreement is finalized (or a court ruling determines ownership), a further standard inheritance registration reflecting this final outcome must still be filed, generally within three years of that agreement or ruling (RPRA Art. 76-3, Para. 4). The Sōzokunin Shinkoku Tōki itself is typically not erased from the registry even after the final registration.

This simplified option provides breathing room for heirs dealing with complex inheritance settlements, allowing them to meet the initial deadline while continuing negotiations or legal procedures. However, relying solely on this indefinitely leaves the final ownership unclear on the public record.

What Counts as a "Justifiable Reason" for Delay?

The law allows for exceptions to the three-year deadline if there is a "justifiable reason" (seitō na riyū). While the specific scope is determined case-by-case, official guidance suggests reasons might include:

- Situations involving an extremely large number of heirs requiring extensive time for investigation.

- Ongoing legal disputes concerning the validity of a will or the scope of inherited property.

- Cases where the applicant is severely ill or facing circumstances making it practically impossible to proceed with the registration.

Reasons such as simply being unaware of the law, being too busy, or finding the process expensive are generally not considered justifiable. If the deadline is approaching and a final settlement seems unlikely, utilizing the Sōzokunin Shinkoku Tōki system is the recommended approach to avoid potential penalties.

Implications for US Companies and Expatriates

The mandatory registration requirement presents specific considerations for foreign entities and individuals with ties to Japanese real estate:

- Direct Ownership and Succession:

- If a US company holds Japanese real estate through a local subsidiary or branch, the succession of ownership upon the dissolution or relevant event concerning the holding entity needs proper registration reflection, though corporate succession differs from individual inheritance.

- If a US-based company directly inherits Japanese real estate (a less common scenario, often requiring specific legal structuring), it becomes directly subject to the registration rules.

- American citizens residing in Japan (expatriates) or those living abroad who inherit Japanese property are directly bound by the three-year registration deadline. Their heirs, regardless of nationality or residence, will also face this obligation upon subsequent inheritance.

- Cross-Border Documentation Challenges:

- Proving inheritance relationships often relies on Japan's family register (koseki) system. For foreign heirs or deceased individuals without a koseki, obtaining equivalent official documentation from the US (e.g., birth certificates, death certificates, marriage certificates, court orders establishing heirship, affidavits) that satisfies the Legal Affairs Bureau can be challenging and time-consuming. Sworn translations are typically required.

- Requirements for documents like registered seal certificates (inkan shōmeisho) for inheritance division agreements can be problematic for non-residents. Alternatives like signature certificates (shomei shōmeisho) obtained from Japanese embassies/consulates abroad are often necessary but add complexity.

- Foreign Wills and Inheritance Laws:

- While Japan generally recognizes foreign wills if validly executed under the relevant foreign law (Act on General Rules for Application of Laws, Art. 37), applying them to Japanese real estate can involve complexities in proving validity and interpreting terms for the Japanese registry.

- The substantive rules governing who inherits and in what shares are typically determined by the deceased's national law (Act on General Rules for Application of Laws, Art. 36). Reconciling US state inheritance laws with Japanese registration procedures requires careful handling.

- Need for Local Representation and Expertise:

- Navigating the Japanese legal system, language barriers, and specific documentation requirements often necessitates appointing local legal counsel (弁護士 - bengoshi) or, very commonly for registration procedures, a judicial scrivener (司法書士 - shihō shoshi). Judicial scriveners specialize in registry applications and preparing related documents.

- Foreign heirs without a presence in Japan may need to appoint a resident agent or attorney to manage the process. Recent rules also emphasize the need to register a domestic contact address for foreign property owners, adding another layer of administration.

- Increased Importance of Proactive Estate Planning:

- For US individuals holding Japanese property, the mandatory registration underscores the importance of clear estate planning, potentially including well-drafted wills recognized under Japanese law or considering structures like trusts to simplify future succession and avoid burdening heirs with complex registration tasks.

Practical Steps and Considerations

For US companies and individuals potentially affected:

- Identify Potential Interests: Review any direct or indirect holdings involving Japanese real estate. Understand the current registered ownership.

- Monitor Key Individuals: For corporate holdings or family properties, be aware of the status of registered owners and have contingency plans for inheritance events.

- Act Promptly Upon Inheritance: If an inheritance involving Japanese property occurs, initiate the process of identifying heirs and gathering documentation immediately. Do not wait until the three-year deadline approaches.

- Engage Local Professionals: Secure qualified Japanese legal counsel and/or a judicial scrivener early in the process, particularly for cross-border situations. Their expertise is invaluable for navigating procedures and document requirements.

- Consider Simplified Registration: If finalizing the inheritance division will take time, utilize the Sōzokunin Shinkoku Tōki (Heir Reporting Registration) to meet the initial deadline and avoid potential fines.

- Budget for Costs: Factor in potential costs for document procurement, translations, professional fees (lawyers, scriveners), and registration taxes.

Conclusion: Compliance is Key

The mandatory inheritance registration system marks a significant shift in Japanese real property law, moving from an optional practice to a legal obligation with potential penalties. Driven by the need to combat the growing problem of ownerless land, this change aims to enhance registry accuracy and facilitate smoother land use and transactions in the long run.

For US companies and expatriates with interests in Japanese real estate, proactive attention to this requirement is essential. Understanding the deadlines, procedures (including the simplified reporting option), documentation challenges, and the necessity of local professional assistance is crucial for ensuring compliance, avoiding fines, and managing property interests effectively in Japan's evolving legal environment. Ignoring this obligation can lead to future complications far exceeding the cost and effort of timely registration.

- Navigating Japan’s Land-with-Unknown-Owners Crisis: New Laws and Business Implications

- Derivative vs. Original Acquisition of Rights in Japan: Key Differences for U.S. Investors

- Real Estate Auctions in Japan: A Primer on Commencement, Seizure and Sale Conditions

- Ministry of Justice — Mandatory Inheritance Registration (English)

https://www.moj.go.jp/EN/MINJI/m_minji07_00004.html