Majority Rules: Designating Shareholder Rights for Co-Owned Stock in Japan

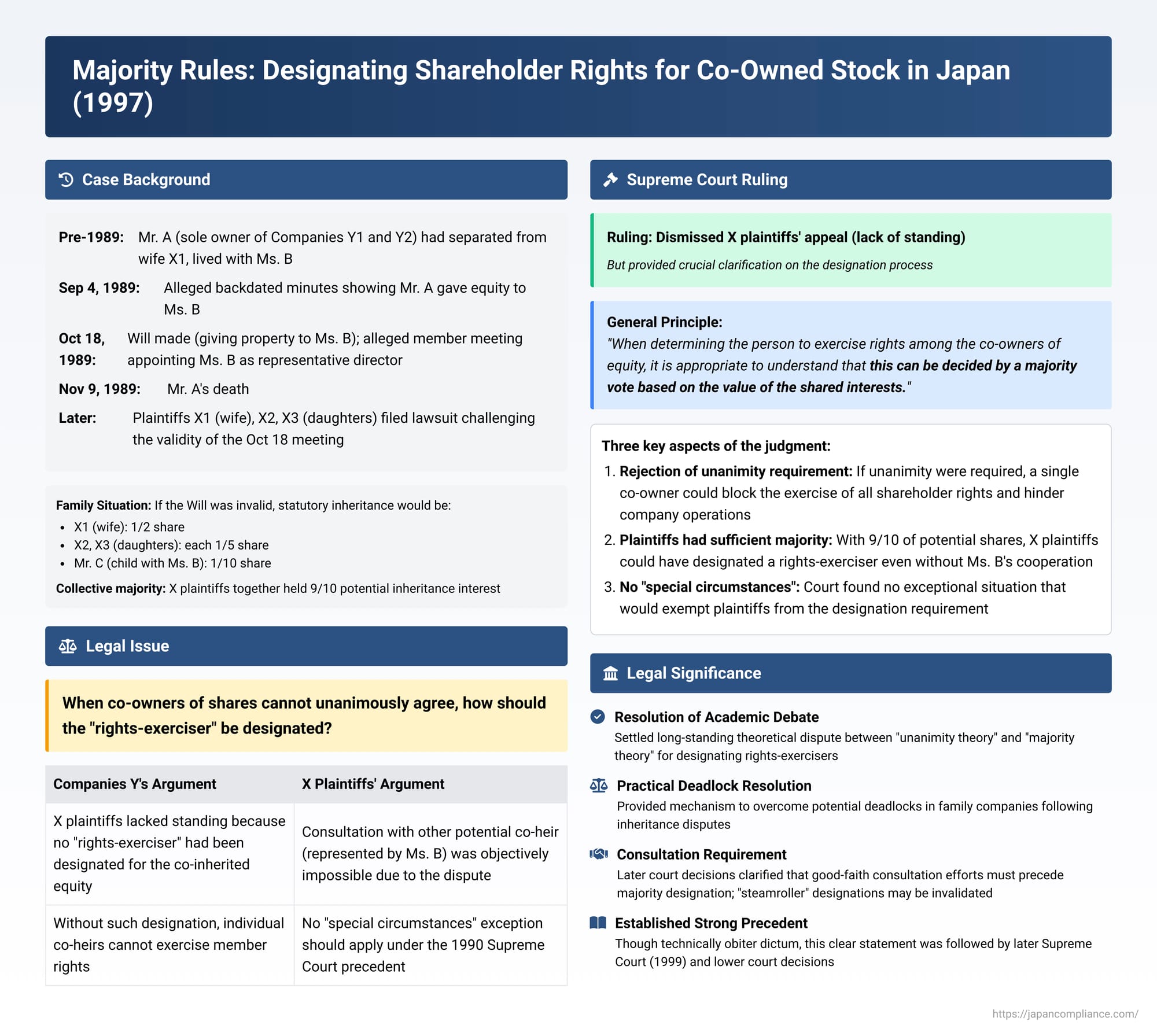

When an individual who owns all the shares or equity in a company passes away, their holdings typically become the joint property of their heirs. This co-ownership can lead to complex governance issues, especially if the heirs are in disagreement. Japanese company law stipulates that co-owners of shares must designate a single person to exercise the rights associated with those shares and notify the company of this designation. Without such a "rights-exerciser," shareholder rights generally cannot be exercised. A key question that arose was how this designation should be made if the co-owners could not unanimously agree. A Japanese Supreme Court decision on January 28, 1997, provided a significant clarification, endorsing a majority-rule approach for this designation.

The Facts: A Disputed Inheritance and a Battle for Company Control

The case revolved around the equity (mochibun) in two limited liability companies, Company Y1 and Company Y2 (collectively "Companies Y"). Mr. A, the sole owner of all equity in both companies and their representative director, passed away on November 9, 1989. This event set the stage for a complex inheritance dispute.

Mr. A had been married to Ms. X1, with whom he had two daughters, Ms. X2 and Ms. X3 (these three—the wife and two daughters—were the plaintiffs, collectively "the X plaintiffs"). However, around 1974, Mr. A had separated from Ms. X1 and subsequently lived with Ms. B, with whom he had a child, Mr. C. Mr. A had maintained his family with Ms. B while also providing financial support for his daughters, Ms. X2 and Ms. X3. Attempts at divorce from Ms. X1 had been unsuccessful.

Around the time of Mr. A's illness and death, several events concerning the ownership and management of Companies Y transpired:

- Alleged Lifetime Gift: On September 4, 1989, Mr. A purportedly instructed Mr. D to prepare minutes for members' meetings of Companies Y1 and Y2. These minutes, backdated to the companies' respective fiscal year-ends, allegedly recorded that Mr. A had gifted all his equity in both companies to Ms. B, and that these gifts had been approved by the companies' members. Mr. A reportedly signed these minutes.

- Will and Disputed Resolutions: A will dated October 18, 1989 ("the Will") was said to exist, under which Mr. A bequeathed all his property to Ms. B. On the same date, minutes were drafted for members' meetings of Companies Y1 and Y2. These minutes documented resolutions appointing Ms. B and a Mr. E as directors, Mr. D as an auditor, and Ms. B as the representative director of both companies ("the Disputed Resolutions"). These appointments were subsequently registered in the commercial registry.

The X plaintiffs (Mr. A's estranged wife and their two daughters) contested these developments. They filed a lawsuit seeking a judicial declaration that the members' meetings supposedly held on October 18, 1989, never actually occurred, and therefore, the Disputed Resolutions appointing Ms. B and others were non-existent. The validity of the Will itself was also being challenged by the X plaintiffs in separate legal proceedings, which were still pending at the time of the Supreme Court appeal in this case.

The Core Issue: Standing to Sue Without Unanimous Designation

A central defense raised by Companies Y was that the X plaintiffs lacked legal standing (genkoku tekikaku) to bring their lawsuit. The companies argued that even if the alleged lifetime gift and the Will in favor of Ms. B were ultimately found to be invalid (meaning the X plaintiffs, along with Mr. C, would be the joint heirs of Mr. A's equity), the co-heirs had failed to designate a single "person to exercise rights" (kenri kōshisha) and notify the companies of this designation, as required by the Limited Company Law (Article 22, incorporating by reference then-Commercial Code Article 203, Paragraph 2, which is analogous to Article 106 of the current Companies Act). Without such designation, the companies contended, an individual co-heir could not exercise shareholder/member rights, including the right to challenge company resolutions.

The lower courts (Tokyo District Court and Tokyo High Court) agreed with this defense and dismissed the X plaintiffs' suit on the grounds that they lacked standing. While acknowledging that Mr. A might have intended to gift the equity to Ms. B, the courts found no evidence that Ms. B was aware of or had accepted this gift during Mr. A's lifetime. More critically for the appeal, they held that even if the X plaintiffs were co-heirs, their failure to designate a rights-exerciser was fatal to their standing, finding no "special circumstances" (an exception established in a 1990 Supreme Court case, see case #9 in the Hyakusen series) that would excuse this requirement. The High Court specifically noted that although the X plaintiffs had not initiated or participated in discussions with the other potential co-heir (Mr. C, represented by Ms. B) to designate a rights-exerciser, it could not be concluded that such discussions were objectively impossible.

The X plaintiffs appealed to the Supreme Court, challenging, among other things, the High Court's assessment that consultation for designating a rights-exerciser was not impossible. Their statutory inheritance shares (if the Will was invalid) would have given Ms. X1 a 1/2 share, Ms. X2 and Ms. X3 each a 1/5 share, and Mr. C (Mr. A's child with Ms. B) a 1/10 share.

The Supreme Court's Key Rulings: Clarifying the Path Forward

The Supreme Court, in its Third Petty Bench judgment of January 28, 1997, dismissed the X plaintiffs' appeal, ultimately agreeing that they lacked standing. However, in doing so, it made a crucial pronouncement regarding the method for designating a rights-exerciser for co-owned equity.

1. Reaffirmation of the General Rule on Standing:

The Court began by reiterating the established principle:

- Co-heirs who come to jointly own equity in a limited company through inheritance must, in order to sue for a declaration of non-existence of a members' meeting resolution based on their status as co-owning members, generally have a "person to exercise rights" designated among them.

- This designation must be notified to the company.

- If this designation and notification are lacking, the co-heirs generally do not have standing to bring such a suit, absent "special circumstances." The Court explicitly referenced its earlier judgment of December 4, 1990 (the subject of case #9 in the Hyakusen series), which had established this "special circumstances" exception.

2. The Method of Designation: Majority Vote by Value of Shared Interests:

This was the most significant part of the ruling. The Court stated:

"And, in this case, when determining the person to exercise rights among the co-owners of equity, it is appropriate to understand that this can be decided by a majority vote based on the value of the shared interests (持分の価格に従いその過半数をもってこれを決することができる - mochibun no kakaku ni shitagai sono kahansū o motte kore o kessuru koto ga dekiru)."

3. Rationale for the Majority Rule:

The Supreme Court provided a clear justification for adopting the majority rule for designation:

"Because, if it were held that a rights-exerciser cannot be designated unless all co-owners unanimously agree, then if even one of the co-owners objects, it would not only render it impossible for any of the co-owners to exercise their membership rights but also risk hindering the company's operations. This would also result in a consequence contrary to the purpose of the aforementioned regulation [requiring designation], which was established considering the company's administrative convenience."

4. Application to the Case at Hand:

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court addressed the X plaintiffs' situation:

- The statutory heirs were Ms. X1 (1/2 share), Ms. X2 (1/5), Ms. X3 (1/5), and Mr. C (1/10). The X plaintiffs (X1, X2, X3) collectively held a clear majority (1/2 + 1/5 + 1/5 = 9/10) of the potential inheritance interest if the Will benefiting Ms. B was invalid.

- The Court reasoned that even if Ms. B (acting for herself or as legal representative for Mr. C, depending on the scenario) refused to participate in discussions to designate a rights-exerciser, it was not impossible for Mr. A's heirs (among whom the X plaintiffs held a majority interest) to designate such a person by a majority vote based on their respective shares.

- Since the X plaintiffs had not undertaken this procedure—they had not attempted to designate a rights-exerciser by majority vote and notify Companies Y—they could not be granted standing to bring their lawsuits.

- The Court explicitly stated that it found no "special circumstances" in this case that would make the designation and notification of a rights-exerciser unnecessary.

Consequently, the Supreme Court upheld the lower courts' dismissal of the X plaintiffs' lawsuit due to lack of standing.

The Significance of the "Majority Rule" for Designating a Rights-Exerciser

While the X plaintiffs ultimately lost their appeal, the Supreme Court's clear pronouncement on the "majority rule" for designating a rights-exerciser was a landmark clarification.

- Resolving Deadlock: Prior to this judgment, there had been a significant academic debate between the "unanimity theory" (requiring all co-owners to agree) and the "majority theory." The unanimity theory, while aiming to protect minority co-owners, could easily lead to deadlock, paralyzing the exercise of shareholder rights if even one co-owner dissented. The majority rule, as endorsed by the Supreme Court, provides a practical mechanism to overcome such deadlocks and enable the co-owned shares/equity to be represented and voted.

- Balance of Interests: The Court's rationale emphasized administrative convenience for the company and the need to prevent disruption to company operations, which could occur if shareholder rights became completely unexercisable. This approach shifts the balance away from a de facto veto power for minority co-owners in the designation process.

- Strong Precedent: Although technically an obiter dictum in this specific judgment (as the X plaintiffs had not even attempted a majority designation), the PDF commentary notes that this clear statement on majority rule was subsequently followed and treated as authoritative by the Supreme Court in a later case (Sup. Ct. Dec. 14, 1999) and by lower courts, effectively establishing it as the prevailing legal standard.

The Role of Consultation Among Co-owners

While the Supreme Court endorsed the majority rule for designation, the judgment also implied that the X plaintiffs could have designated a rights-exerciser, suggesting a procedural path was available to them. The PDF commentary discusses how lower courts have since grappled with the issue of consultation among co-owners prior to a majority designation:

- Some cases have upheld a majority designation as valid even when a minority co-owner refused to participate in consultations, provided they were given an opportunity to do so.

- However, other cases have invalidated designations where the majority merely went through the motions of consultation ("formally as if consultation occurred") without genuine, good-faith efforts, especially in highly contentious situations such as pending estate division litigation or disputes over the validity of wills affecting share ownership. Such "steamroller" designations have been deemed an abuse of rights.

- This suggests that while a majority can ultimately decide, a good-faith attempt at consultation with all co-owners is generally expected. The absence of genuine consultation, particularly if coupled with other factors suggesting an attempt to unfairly exclude minority co-owners or preempt ongoing legal processes concerning the shares' ultimate ownership, can lead to a majority designation being invalidated as an abuse of rights. The commentary notes that courts are particularly cautious when (a) the ultimate ownership of the shares is still in flux due to pending litigation about wills or estate division, and (b) the designation and subsequent exercise of rights could decisively alter company control.

"Special Circumstances" Exception Revisited

The Supreme Court in this case reaffirmed the "special circumstances" exception (established in its December 4, 1990, ruling) that might allow a co-heir to sue without a formal designation of a rights-exerciser.

- Such circumstances typically arise when the company's litigation posture is inherently contradictory—for example, if the company defends the validity of a shareholder resolution (which presumes shareholder rights were validly exercised by or on behalf of the co-owners) while simultaneously arguing that a plaintiff co-heir lacks standing because no rights-exerciser was designated for those same co-owned shares.

- In the present case, the Supreme Court found no such "special circumstances." The PDF commentary suggests this might be because the Disputed Resolutions were arguably based on Ms. B's claim to ownership (via the alleged gift or the Will), rather than on any purported collective action by all co-heirs of Mr. A. Thus, the company's defense of those resolutions might not have created the same direct contradiction with its challenge to the X plaintiffs' standing based on their (potential) inherited shares.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's January 28, 1997, decision provided a critical and practical clarification regarding the governance of co-owned company shares or equity in Japan, particularly in the often-fraught context of inheritance by multiple heirs. By endorsing the principle that the "person to exercise rights" for such co-owned interests can be designated by a majority vote based on the value of those interests, the Court offered a way to prevent paralysis in the exercise of shareholder rights due to dissent from a minority of co-owners. While the X plaintiffs in this specific instance were found to lack standing because they had not even attempted this majority designation process, the ruling's articulation of the majority rule principle has had a lasting impact. It aims to facilitate corporate functionality while acknowledging, through subsequent lower court interpretations, the need for good-faith consultation among co-owners and the potential for judicial intervention if the majority rule is exercised abusively, especially amidst unresolved disputes over the ultimate ownership of the inherited equity.