Love, Promises, and Heartbreak: A 1963 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Broken Engagements and Compensation

Date of Judgment: September 5, 1963

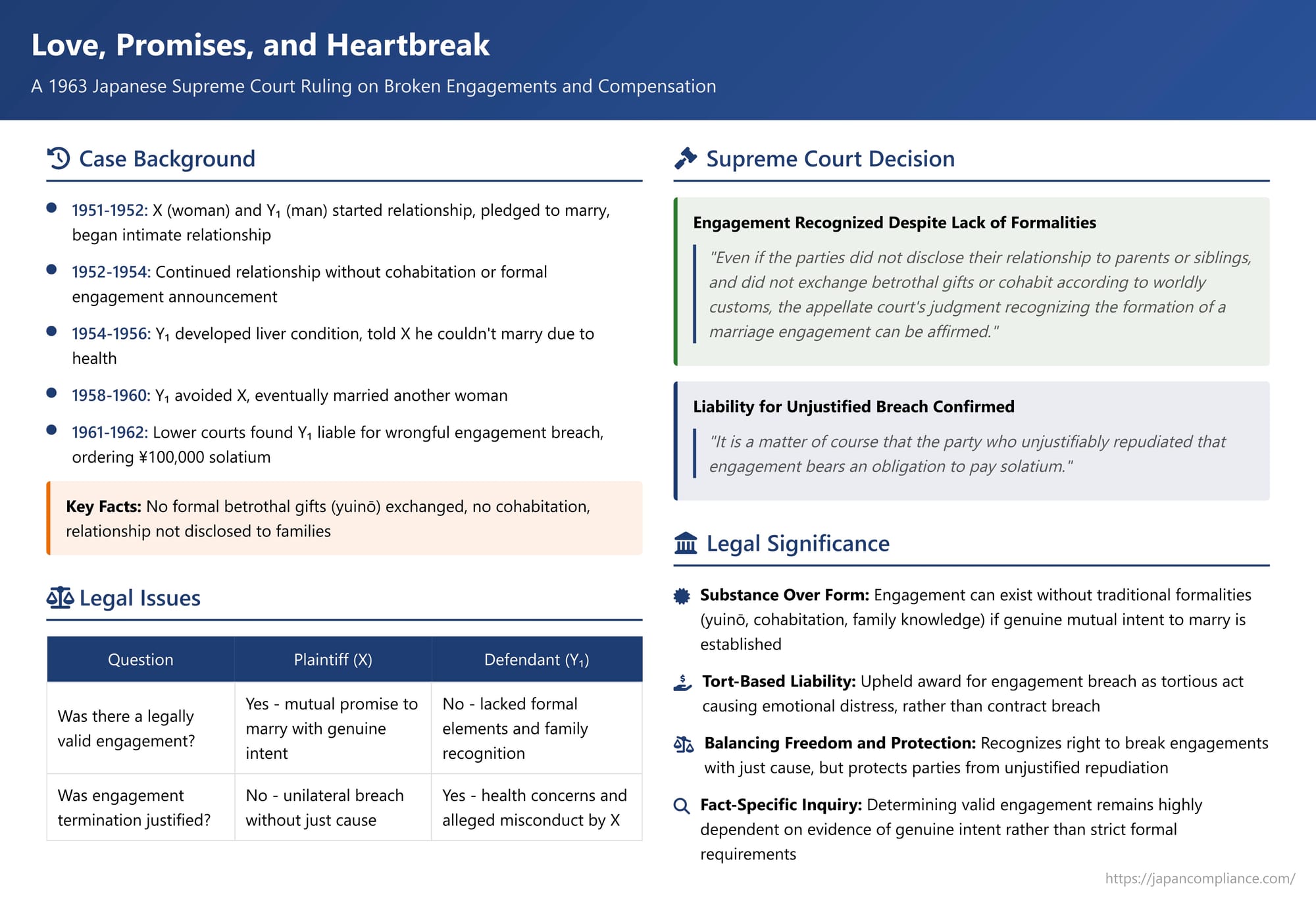

The path to marriage often begins with a promise, an engagement—known in Japanese legal contexts as a "marriage reservation" (婚姻予約 - kon'in yoyaku). This understanding between two individuals to marry in the future carries significant emotional and often practical weight. But what happens when this promise is broken? If one party unilaterally terminates the engagement without just cause, can the other seek compensation for the emotional distress and other damages incurred? And what constitutes a legally recognized engagement, especially when traditional formalities like exchanging betrothal gifts or cohabitation are absent? The Supreme Court of Japan delved into these sensitive questions in a notable decision on September 5, 1963 (Showa 37 (O) No. 1200).

The Facts: A Long Relationship, Broken Promises, and a Claim for Solatium

The case involved X, a 21-year-old woman, and Y₁, a 21-year-old man, who resided in a town in Hokkaido and had known each other for a long time. Their relationship deepened around August 1951, and by September of the following year (1952), they had pledged to marry in the future and began a sexual relationship.

For several years, until around the summer of 1954, X and Y₁ continued their intimate relationship, often meeting in places like a storage shed or on the beach. However, they did not cohabit, nor did they disclose their relationship or marriage plans to their parents or siblings. There was no formal exchange of betrothal gifts (結納 - yuinō), a traditional marker of engagement in Japan.

Around the summer of 1954, Y₁ fell ill with a liver condition. From the summer to the end of 1956, he stayed in Q village in Hiyama district for treatment. During this period, around September, X visited Y₁ in Q village, and they stayed together at an inn. The following month, Y₁ traveled to Hakodate, where X was, and told her that given his poor health, he could not consider marriage. X did not agree with this. It was also asserted by X that she had become pregnant twice during their relationship (allegedly in April 1953 and February 1957) and had undergone abortions each time at Y₁'s request.

After his illness, Y₁, still in poor health, began assisting in the family business of his father, Y₂. From around May 1958, Y₁ started avoiding X. In March 1960, Y₁ entered into a de facto marriage with another woman, A.

Feeling that Y₁ had unilaterally broken their marriage engagement and alleging that Y₂ (Y₁'s father) had coerced Y₁ into separating from her, X filed a lawsuit. She claimed damages for emotional distress (solatium) based on what she asserted was a joint tortious act by Y₁ and Y₂.

The first instance court (Hakodate District Court, September 11, 1961) dismissed X's claim against Y₂ (the father), finding no evidence that he had forced the separation. However, it found Y₁ (the son) liable for wrongfully breaking the marriage engagement with X without just cause and ordered him to pay X 100,000 yen as solatium. Y₁ appealed this decision. The second instance court (Sapporo High Court, Hakodate Branch, July 10, 1962) upheld the first instance court's judgment regarding Y₁'s liability and dismissed his appeal. Y₁ then appealed to the Supreme Court. His arguments included that the facts did not support the finding of a formal marriage engagement.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Upholding the Engagement and Liability for its Breach

The Supreme Court dismissed Y₁'s appeal, affirming the lower courts' judgments.

Affirming the Existence of a Marriage Engagement:

The Court stated: "The appellate court... found that X, in response to Y₁'s marriage proposal, agreed to it with the genuine intention of conducting a shared life as husband and wife, and thereafter continued a physical relationship for a long period. The marital intentions of both parties were clear, and it was not a mere illicit or clandestine affair. This finding is not unsupportable."

Crucially, the Court continued: "Given these findings, even if, during that time, the parties did not disclose their relationship to their parents or siblings, and did not exchange betrothal gifts or cohabit according to worldly customs, the appellate court's judgment recognizing the formation of a marriage engagement can be affirmed."

Liability for Unjustified Breach:

Having affirmed the existence of a valid marriage engagement, the Court then addressed the consequences of its breach: "Since the appellate court... has found that a marriage engagement was formed between Y₁ and X, it is a matter of course that the party who unjustifiably repudiated that engagement bears an obligation to pay solatium."

The Significance of the Ruling: Defining Engagement and Its Consequences

This 1963 Supreme Court decision carries several important points of significance for understanding marriage engagements in Japanese law:

- Formation of a Marriage Engagement Without Formalities: The most prominent aspect of this ruling is its affirmation that a legally binding marriage engagement can be formed even in the absence of traditional formalities such as the exchange of betrothal gifts (yuinō) or cohabitation, and even if the relationship has not been disclosed to the parties' families. The decisive factor is the clear and mutual "intention to marry" and to establish a genuine spousal life together. In this case, the long-term intimate relationship, coupled with what the lower courts found to be a clear agreement to marry, was deemed sufficient. This followed an earlier Daishin'in (Great Court of Cassation) precedent from Showa 6 (1931) which also held that an engagement could exist without formalities if "the man and woman, with sincerity and good faith, make this contract with the expectation of becoming husband and wife in the future." However, the factual background of that earlier "sincerity and good faith" case involved cousins whose relationship and intentions seemed to be known within their families, making the 1963 ruling's application to a more clandestine relationship notable.

- Damages for Unjustified Breach (as a Tort): The judgment upheld the award of solatium to X based on Y₁'s unjustified repudiation of the engagement, framing it as a tortious act. This differed from some earlier precedents, such as a Daishin'in ruling from Taisho 4 (1915), which, while recognizing the validity of "marriage reservations" (a term then often used to describe de facto marriages rather than mere engagements), had treated their breach as a matter of contractual default (債務不履行 - saimu furikō). The 1963 Supreme Court did not delve into whether a contractual claim would also have been possible, but by upholding the tort claim, it affirmed that the unjustified breaking of an engagement can constitute a wrongful act causing compensable emotional harm.

What Constitutes a Marriage Engagement? Beyond Outward Signs

The question of when a relationship transitions from mere dating to a legally cognizable "marriage engagement" is highly fact-dependent.

- The "Sincerity and Good Faith" Standard: The courts look for a genuine and mutual understanding and intention between the parties to marry in the future.

- Objective Indicators: While this Supreme Court ruling established that traditional formalities are not strictly necessary, their presence or absence still plays an evidentiary role.

- Courts generally find an engagement to exist when there has been an exchange of betrothal gifts, introduction to parents, setting of a wedding date, or joint preparations for married life.

- Even without these, if parents and relatives are aware of the couple's promise to marry and their close relationship, or if one party introduces the other as their fiancé(e) while cohabiting, an engagement may be recognized. Sending affectionate letters or cards explicitly discussing marriage can also be evidence.

- Conversely, if such objective indicators are lacking, and discussions about the future are vague or infrequent, courts are less likely to find a formal engagement, even if there has been a sexual relationship. For example, statements like "Let's live together before it gets cold" sent by email, or a one-time mention of "Let's get together even if our parents oppose," have been found insufficient in other cases.

In the present 1963 case, the lower courts' finding of a "clear marital intention" in both X and Y₁ was primarily based on their agreement to marry followed by a "long-continued physical relationship." The commentary suggests this finding was somewhat tenuous given the lack of other external indicators and the clandestine nature of their relationship. The fact that X underwent two abortions, allegedly at Y₁'s request, might have been a factor, though this was not explicitly highlighted by the Supreme Court as a basis for finding the engagement. The commentary notes that this specific judgment, due to its somewhat unique factual basis for inferring clear marital intent, may not have had a sweeping influence on subsequent case law regarding the formation of engagements with minimal external evidence.

Freedom to Change One's Mind vs. Protection of Expectations

A central tension in engagement law is balancing the freedom of individuals to change their minds about marriage against the need to protect the reliance interest and emotional well-being of the other party who believed in the promise.

- Unjustified Breach: If one party unilaterally breaks off an engagement without a valid reason, they can be held liable for damages. Valid reasons might include the discovery of serious misconduct by the other party (e.g., violence, infidelity by the other party) that fundamentally undermines the basis of the intended marriage.

- Mutual Responsibility or Unclear Fault: If the breakdown of the engagement is due to mutual disagreement, irreconcilable differences in values, or circumstances where neither party is clearly at fault (e.g., persistent and strong parental opposition that cannot be overcome despite efforts), liability is less likely to be imposed. For instance, cases where a party developed anxieties about the other's social skills or family compatibility, or where fundamental value differences emerged, have resulted in no liability for breaking the engagement.

- Duty to Communicate and Cooperate: The dominant academic view, and one reflected in some lower court cases, is that parties to an engagement have a duty to act with sincerity and make efforts towards achieving the marriage. A breach of this duty (e.g., by not engaging in constructive discussions about problems, or by making unreasonable demands that sabotage wedding preparations) can lead to liability if the engagement is then broken off due to such conduct.

The Supreme Court in this 1963 case did not deeply analyze Y₁'s reasons for breaking the engagement beyond noting the lower courts found it "unjustified." The lower courts had rejected Y₁'s claims about X's alleged misconduct (rumors of relationships with other men) as unproven. The fact that Y₁ cited his ill health as a reason to X, but X did not agree, and Y₁ later married another woman, likely contributed to the finding that his repudiation was unilateral and without sufficient justification concerning X's conduct.

The Nature of Liability: Tort vs. Contract

While earlier precedents often framed liability for broken engagements as a breach of contract (failure to fulfill the "promise to marry"), this Supreme Court decision upheld a judgment based on tort law—the wrongful infringement of X's legally protected interest in the expectation of marriage and the emotional distress caused by the unjustified repudiation.

The commentary notes that in practice, the distinction between these two legal theories (contract vs. tort) may not always be sharply delineated in claims for damages arising from broken engagements, as the core issue is the unjustified termination of the relationship and the resulting harm. Both theories have been used in Japanese case law.

Conclusion: Affirming Protection for Serious Marital Promises

The 1963 Supreme Court decision is significant for affirming that a serious and clear mutual intention to marry, even without traditional outward formalities like betrothal gifts or cohabitation known to families, can constitute a legally recognized marriage engagement in Japan. Furthermore, it reinforces the principle that the unjustified repudiation of such an engagement by one party can give rise to a claim for solatium by the other party, based on the emotional distress and harm caused by the breach. While societal norms around engagements and marriage have evolved since 1963, this ruling remains a key precedent illustrating the law's willingness to protect sincere expectations formed in anticipation of marriage and to provide redress when those expectations are wrongfully shattered. It underscores that a promise to marry, when clearly and mutually intended to lead to a shared life, is not a commitment to be undertaken or abandoned lightly.