Love, Lies, and State Secrets: How Japan's Supreme Court Drew the Line for Investigative Journalism

Decision Date: May 31, 1978

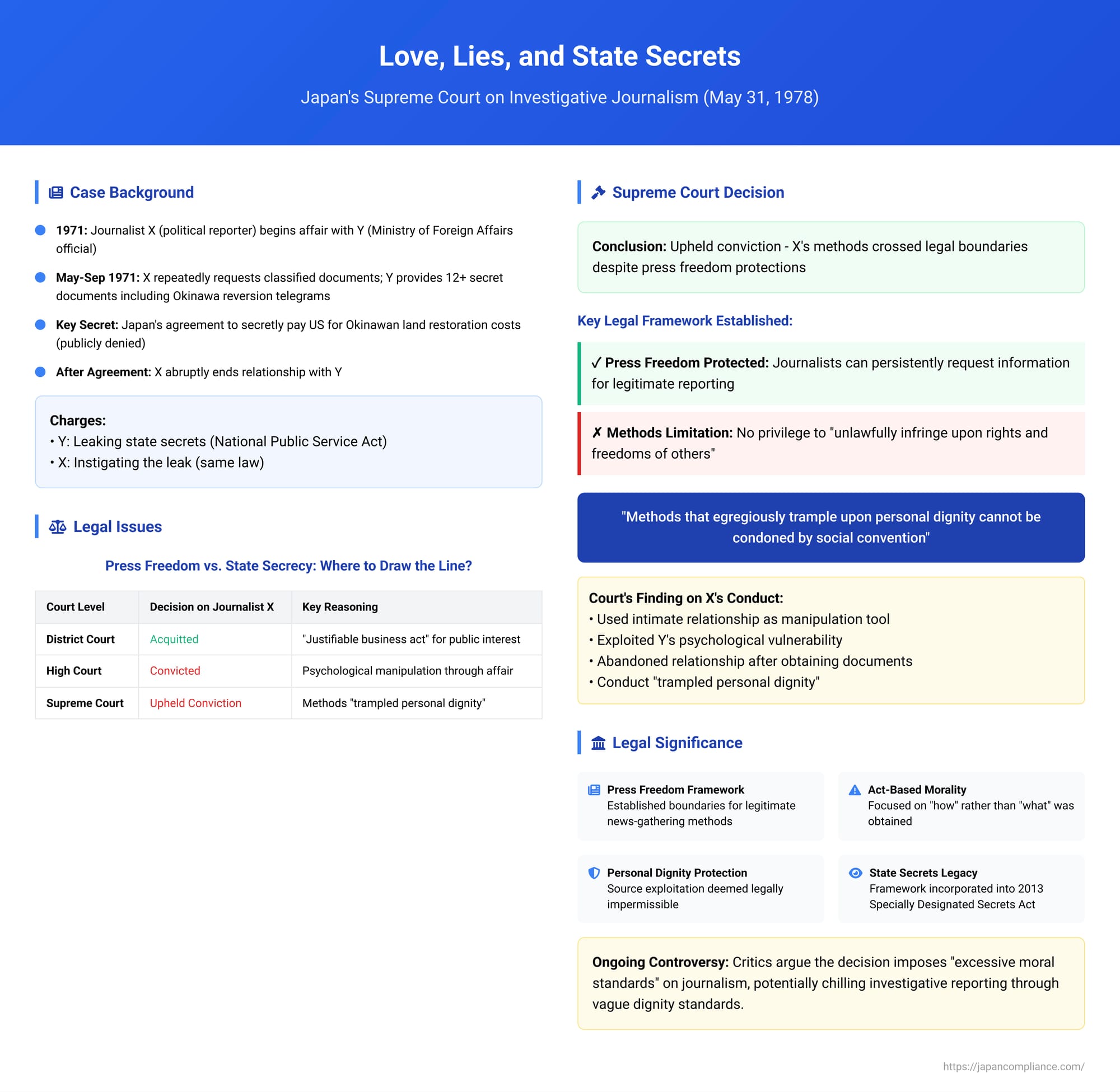

The relationship between a free press and a functioning government is one of inherent and perpetual tension. Journalists, driven by the public's right to know, strive to uncover information that governments, citing national security or diplomatic necessity, labor to keep secret. In 1978, this fundamental conflict erupted into one of modern Japan's most sensational and politically charged legal battles. The case, known as the "Okinawa Secret Pact Incident," involved a prominent journalist, a female diplomat, an intimate affair, and a leaked state secret that shook the foundations of Japanese politics. The resulting Supreme Court decision on May 31, 1978, established a crucial and controversial precedent on the legal limits of news-gathering, drawing a line in the sand based not on the importance of the secret revealed, but on the morality of the methods used to obtain it.

The Factual Background: A Relationship and a Revelation

The story unfolded against the backdrop of the 1971 negotiations for the reversion of Okinawa from United States control to Japan, a moment of immense national significance. The key players were X, a male political journalist for a major newspaper, and Y, a female administrative official in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Over several months, X cultivated a relationship with Y, which became a continuous sexual affair. During this time, X repeatedly implored Y to provide him with classified documents related to the ongoing Okinawa negotiations. Between May and September of 1971, Y complied, giving X access to and copies of more than a dozen secret documents.

Among these were three confidential diplomatic telegrams that contained a political bombshell: a "secret pact" in which the Japanese government had agreed to secretly pay the United States for the costs of restoring military-used land on Okinawa to its original state—a financial burden that the government had publicly denied it would shoulder.

The leak eventually came to light, leading to a high-profile prosecution. Y, the official, was charged with leaking state secrets in violation of the National Public Service Act. X, the journalist, was charged with instigating (sosonokashi) her to commit the crime under the same law.

The Journey Through the Courts: A Shifting Legal Focus

The case wound its way through the Japanese legal system, with each court level offering a different perspective on the clash between press freedom and state secrecy.

- The Trial Court: A Victory for the Press. The Tokyo District Court convicted the official, Y (her conviction became final). However, in a stunning decision, it acquitted the journalist, X. The court ruled that X's actions were a form of news-gathering intended to serve the public interest and therefore constituted a "justifiable business act." It placed the burden of proof on the prosecution to show that his methods were not justifiable, a burden it failed to meet.

- The High Court: A Reversal. The prosecution appealed the acquittal. The Tokyo High Court overturned the trial court's decision and found X guilty. The appellate court applied a narrow definition of "instigation," holding that it required solicitation that rendered a public official's free will impossible. However, it found that X's profound psychological influence over Y, stemming from their affair, met this high standard. It also parsed the specific documents, finding that while X might have reasonably believed two were not truly secret, he had no such excuse for the third, crucial telegram revealing the secret pact.

- The Appeal to the Supreme Court. X appealed his conviction, arguing that the so-called secret was an "illegal secret" that the government had no right to conceal from its people, and that his actions as a journalist did not constitute illegal instigation.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: It's Not What You Get, It's How You Get It

On May 31, 1978, the Supreme Court delivered its final judgment. It dismissed X's appeal and upheld his conviction, but in doing so, it laid out a comprehensive legal framework for evaluating the legitimacy of news-gathering activities that continues to be cited to this day.

The Secret Was Legitimate.

First, the Court summarily dealt with the defense's claim that the document was an "illegal secret." It affirmed that the contents of the telegram, which related to ongoing diplomatic negotiations, were non-public information worthy of protection and thus constituted a "secret" under the National Public Service Act.

Freedom of the Press is Respected, But Not Absolute.

The Court then turned to the core issue of press freedom. It began by explicitly recognizing the vital role of the press in a democracy. It stated that reporting on national affairs serves the "people's right to know" and that freedom of the press is an especially important aspect of the freedom of expression guaranteed by Article 21 of the Constitution. To that end, "freedom of news-gathering... must be fully respected."

Crucially, the Court declared that merely persuading or persistently requesting a public official to leak a secret does not automatically render a journalist's conduct illegal. So long as the reporter's actions are "genuinely for the purpose of reporting" and the "means and methods are, in light of the spirit of the entire legal order, condoned as appropriate by social convention," they can be considered a "justifiable business act" and thus lawful.

The Line That Cannot Be Crossed.

Having established this broad protection for journalists, the Court then drew a firm line. It unequivocally stated: "it goes without saying that even the press does not have a special privilege to unlawfully infringe upon the rights and freedoms of others in the course of its news-gathering."

The Court held that a journalist's methods become illegal not only when they involve obvious crimes like bribery or coercion, but also when the methods, though not technically criminal themselves, are of a "mode that egregiously tramples upon the personal dignity of the subject of the news-gathering and cannot be condoned by social convention in light of the spirit of the entire legal order."

Applying the Standard to X's Conduct.

In the Court's view, X's methods had crossed this line. The judgment detailed a narrative of manipulation:

- X initiated the sexual relationship with Y not out of affection, but with the "intention of using her as a means to obtain secret documents from the outset."

- He took advantage of the "psychological state in which she found it difficult to refuse his requests" that arose from their intimate relationship.

- After the Okinawa Reversion Agreement was signed and he no longer needed her as a source, he "abruptly changed his attitude towards her... and the relationship faded," after which he "paid her no further mind."

Based on this sequence of events, the Court concluded that X's conduct "must be said to have egregiously trampled upon the personal dignity of Y, the subject of his news-gathering." His methods were "inappropriate" and "cannot be condoned," thus falling outside the scope of legitimate journalistic activity.

A Controversial Legacy: Act-Based Morality and Its Critics

The Supreme Court's decision is notable for what it chose not to do. It did not engage in a direct balancing of the competing interests at stake—the value of the public learning about the secret pact versus the value of the government maintaining diplomatic secrecy. Instead, it laser-focused its analysis almost entirely on the journalist's methods. This reflects a strong tendency in Japanese jurisprudence toward an "act-based theory of wrongdoing" (kōi mukachi ron), which judges the rightness or wrongness of an act itself, rather than a "result-based theory" (kekka mukachi ron), which would focus on the consequences.

This approach has drawn considerable criticism. While few would defend X's actions as ethically pristine, critics question whether they legally amount to "trampling on personal dignity," especially given that Y was an adult official who consented to the relationship. There is no general crime for injuring a person's dignity in the Japanese penal code. This has led to the charge that the Court imposed an "excessive act-based moralism," using a vague ethical standard to justify a criminal conviction in a case with profound implications for press freedom.

Conclusion

The "Okinawa Secret Pact Incident" remains one of the most significant and debated cases in the history of Japanese law. It firmly established the principle that while freedom of the press is a cornerstone of democracy, it is not a license for journalists to engage in methods that are deemed grossly exploitative or manipulative. The Supreme Court's framework, which privileges the "how" over the "what," allows for aggressive, persistent reporting but withdraws legal protection when a reporter's methods egregiously violate the personal dignity of their source. The legacy of this decision is complex; it simultaneously offers broad protection for legitimate journalistic inquiry while setting a controversial, morality-infused limit that continues to fuel debate about the proper role and responsibilities of the press in a democratic society. With the recent passage of Japan's Act on the Protection of Specially Designated Secrets, which explicitly incorporates the legal framework from this very decision, the ghost of this case continues to shape the landscape of press freedom in Japan today.