Love, Lies, and Lawsuits: Can You Sue Your Spouse's Lover if the Marriage Was Already Over? A 1996 Japan Supreme Court Ruling

Date of Judgment: March 26, 1996

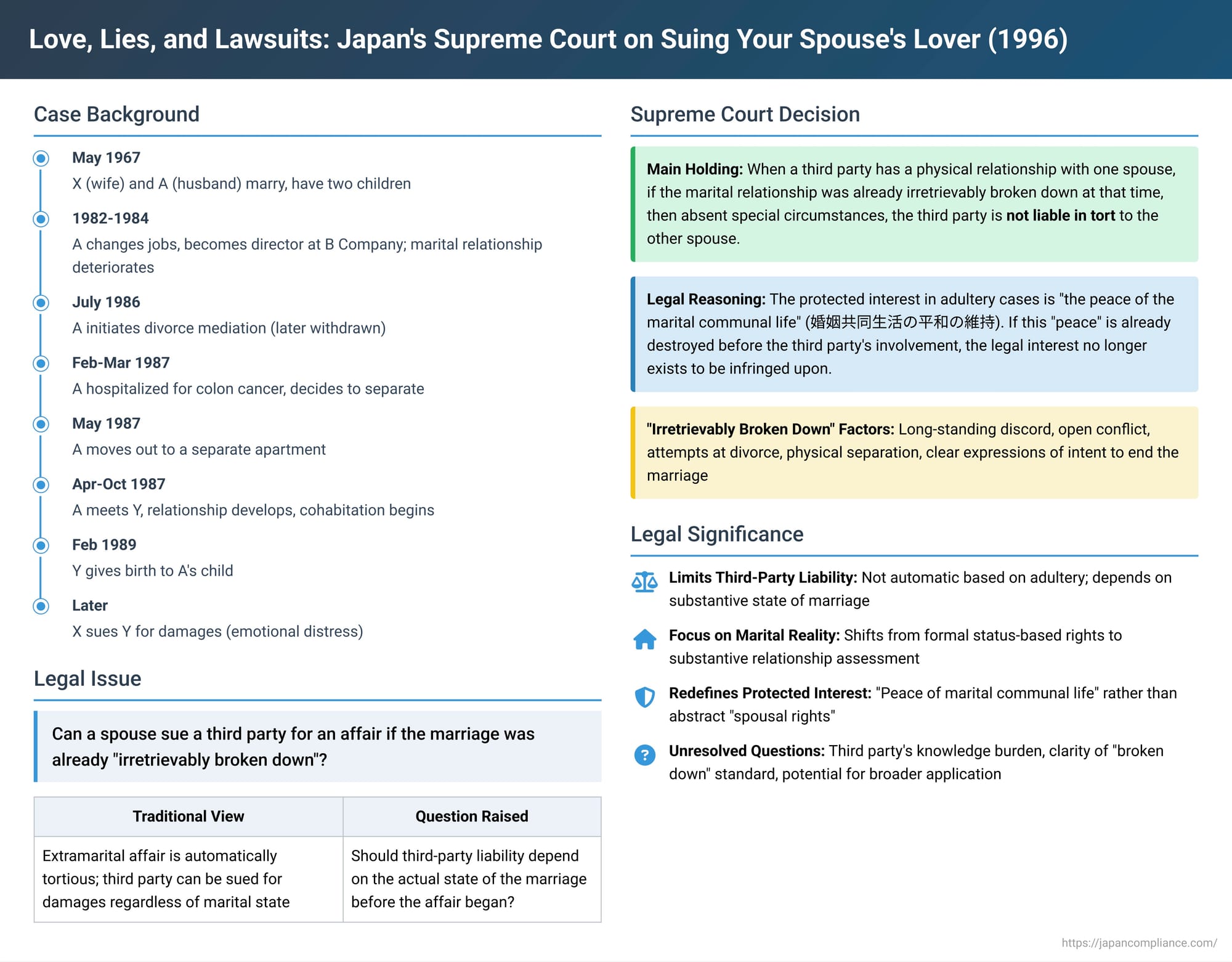

In Japan, engaging in an extramarital affair (不貞行為 - futei kōi) has long been recognized as a tortious act, potentially giving rise to a claim for damages for emotional distress (慰謝料 - isharyō). Traditionally, the "innocent" spouse could seek such damages not only from their unfaithful partner but also from the third party involved in the affair. However, a critical question arises: is this right to sue the third party absolute, or does it depend on the actual state of the marriage itself? Specifically, if a marriage was already "irretrievably broken down" (hatanshiteita) before the affair commenced, can the third party still be held liable? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this nuanced issue in a significant decision on March 26, 1996 (Heisei 5 (O) No. 281).

The Facts: A Deteriorating Marriage and a Subsequent Relationship

The case involved a couple, X (the wife) and A (the husband), who had married in May 1967 and had two children, born in 1968 and 1971. Over time, their marital relationship gradually deteriorated due to various factors, including differences in personality and financial perspectives.

The situation worsened significantly after A changed jobs in 1982 to work for B Company, eventually becoming its representative director in 1984. Amidst growing acrimony, X began demanding a division of property. In July 1986, A initiated divorce mediation proceedings in family court with the intention of separating from X. However, X did not attend the mediation sessions, and A subsequently withdrew his petition.

In February 1987, A was hospitalized for colon cancer surgery and was discharged at the end of March. During his hospitalization, B Company purchased an apartment (referred to as "the current apartment"). Having solidified his intention to separate from X while in the hospital, A moved into this apartment in May 1987, thereby physically separating from X.

Around April 1987, Y (the defendant in this case) met A. A was a customer at a snack bar where Y worked part-time. A informed Y that he was in the process of divorcing his wife. Following A's separation from X and his move into the current apartment alone, A and Y grew closer. By the summer of 1987, their relationship had become physical, and around October 1987, Y began cohabiting with A in the current apartment. In February 1989, Y gave birth to a child fathered by A, whom A legally acknowledged.

X, the wife, subsequently filed a lawsuit against Y, the third party, seeking damages for the emotional distress caused by Y's affair with her husband, A.

The Lower Courts' Stance: No Claim if Marriage Already Broken

Both the court of first instance and the appellate court dismissed X's claim for damages against Y. Their decisions were based on the finding that the marital relationship between X and A was already irretrievably broken down before Y's physical relationship with A began. X then appealed this outcome to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: No Liability Post-Breakdown, Generally

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the lower courts' decisions and establishing an important principle regarding third-party liability in adultery cases.

The Core Principle:

The Court articulated its central holding as follows: "Where a third party (C) has a physical relationship with one spouse (B) of a married couple (A and B), if the marital relationship between A and B was already irretrievably broken down at that time, then, unless special circumstances exist, C is not liable in tort to A [the aggrieved spouse]."

Rationale: The Protected Legal Interest – "Peace of the Marial Communal Life"

The Supreme Court's reasoning hinged on its definition of the legally protected interest that is infringed by an extramarital affair. The Court stated: "This is because C's physical relationship with B constitutes a tort against A... because it can be said to be an act that infringes upon A's right or legally protected interest in maintaining the peace of the marital communal life (婚姻共同生活の平和の維持 - kon'in kyōdō seikatsu no heiwa no iji)."

Crucially, the Court continued: "However, if the marital relationship between A and B was already irretrievably broken down, then, as a general rule, A no longer possesses such a right or legally protected interest." In essence, if the "peace of the marital communal life" has already been destroyed before the third party's involvement, then the third party's actions cannot be said to infringe upon an interest that no longer substantively exists.

Application to the Case and Distinction from Prior Precedent:

The Supreme Court found that the lower courts' determination—that the marriage between A and X was already irretrievably broken when Y's physical relationship with A commenced—was justifiable based on the evidence. Therefore, Y's actions did not illegally infringe upon any existing legally protected interest of X. The Court also distinguished this case from a prior Supreme Court ruling from Showa 54 (1979), which had affirmed third-party liability, by noting that the 1979 case involved a marital relationship that was not broken down prior to the affair.

What Constitutes an "Irretrievably Broken Down" Marriage?

While the Supreme Court's judgment doesn't provide an exhaustive definition of an "irretrievably broken down" marriage, the factual circumstances of X and A's relationship leading up to A's involvement with Y are illustrative. These included:

- Long-standing and escalating marital discord due to differences in personality and financial views.

- Open conflict, including X's demands for property division.

- A formal attempt by A to seek divorce through court-mediated conciliation.

- A's decision, made during a serious illness, to live separately, followed by his actual physical separation from X and move into a new residence.

These factors collectively painted a picture of a marriage that had, for all practical purposes, ceased to function as a "communal life" before Y entered A's life.

Implications of the Ruling: A Shift in Focus

This 1996 decision marked a significant development in Japanese tort law concerning adultery:

- Limits Third-Party Liability: It substantially limits the scope of a third party's liability for engaging in an affair with a married individual. Liability is no longer automatic based simply on the act of adultery; the actual state of the marriage at the time the affair begins is a critical determining factor.

- Focus on Substantive Marital Reality: The ruling shifts the focus from a purely status-based spousal right (e.g., an abstract "right as a spouse" to marital fidelity) to a more concrete and substantive interest in the "peace of the actual, functioning marital communal life." If that peace is already gone due to the actions or inactions of the spouses themselves, a third party's subsequent involvement does not, in principle, cause a new infringement of that specific interest.

Unresolved Questions and Ongoing Academic Debate

Despite the clarity of its core principle, the Supreme Court's decision also highlighted and left open several complex legal and practical questions, which continue to be debated by legal scholars:

- Defining the Protected Legal Interest: Earlier cases, like the Showa 54 (1979) precedent, referred to the infringement of "the other spouse's rights as a husband or wife." This 1996 judgment defined it as the "right or legally protected interest in maintaining the peace of the marital communal life." Some scholars ponder whether this represents a qualitative shift in understanding the protected interest. If the core interest is the "peace of communal life," could this concept potentially extend to non-marital cohabiting relationships, or even form a basis for claims by children affected by a parent's affair? (Notably, the 1979 SC case denied children's direct claims for loss of parental affection due to adultery, absent special circumstances ). The 1996 judgment specifies "marital" communal life, but the conceptual groundwork is a point of discussion.

- Liability Between the Spouses Themselves: The judgment primarily addresses the liability of the third party. It does not fully clarify the tortious liability between the spouses themselves for an act of adultery, especially if the marriage continues (i.e., they don't divorce). The commentary points out that if an aggrieved spouse cannot claim damages from their own unfaithful partner while the marriage is ongoing, but can claim from the third party, this could lead to problematic situations, including the "badger game" (美人局 - tsutsumotase) scenario where a couple might collude to extort money from a third party. Addressing third-party liability without a clear framework for inter-spousal liability remains a challenge.

- The Third Party's Knowledge of the Marital Breakdown: A significant practical question is how a third party is expected to ascertain whether their partner's existing marriage is "irretrievably broken down." Does this ruling implicitly place a duty on the third party to investigate the marital situation of the person they are becoming involved with? The judgment does not directly address this. Resolving this issue by assessing the third party's "negligence" in not knowing the marriage was broken would imply some duty of inquiry, which is a debatable premise for ordinary social interactions.

- Clarity and Predictability of the "Broken Down" Standard: While the principle seems clear, factually determining when a marriage has crossed the threshold into being "irretrievably broken down" can be highly subjective and complex, potentially leading to uncertainty in its application across diverse cases.

Conclusion: A More Nuanced Approach to Adultery Claims

The Supreme Court of Japan's March 1996 decision represents a significant refinement of the law regarding tort claims for adultery. It established the important principle that a third party engaging in an affair with a married individual is generally not liable for damages to the other spouse if the marriage was already irretrievably broken down at the time the affair commenced. This is because the legally protected interest at stake is conceived as the "peace of the marital communal life," an interest that is presumed to no longer exist in a defunct marriage.

This ruling moves away from a model of automatic liability based solely on the act of adultery with a married person, introducing a more fact-sensitive approach that considers the substantive reality of the marital relationship. While it provides greater clarity in one respect, it also underscores the ongoing complexities and debates surrounding the legal treatment of marital infidelity, the nature of spousal rights, and the practical challenges of applying such standards in deeply personal and often emotionally charged situations.