Lost in Transit: Can a Courier's Liability Limit Protect Against Claims from the Recipient? A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Judgment Date: April 30, 1998

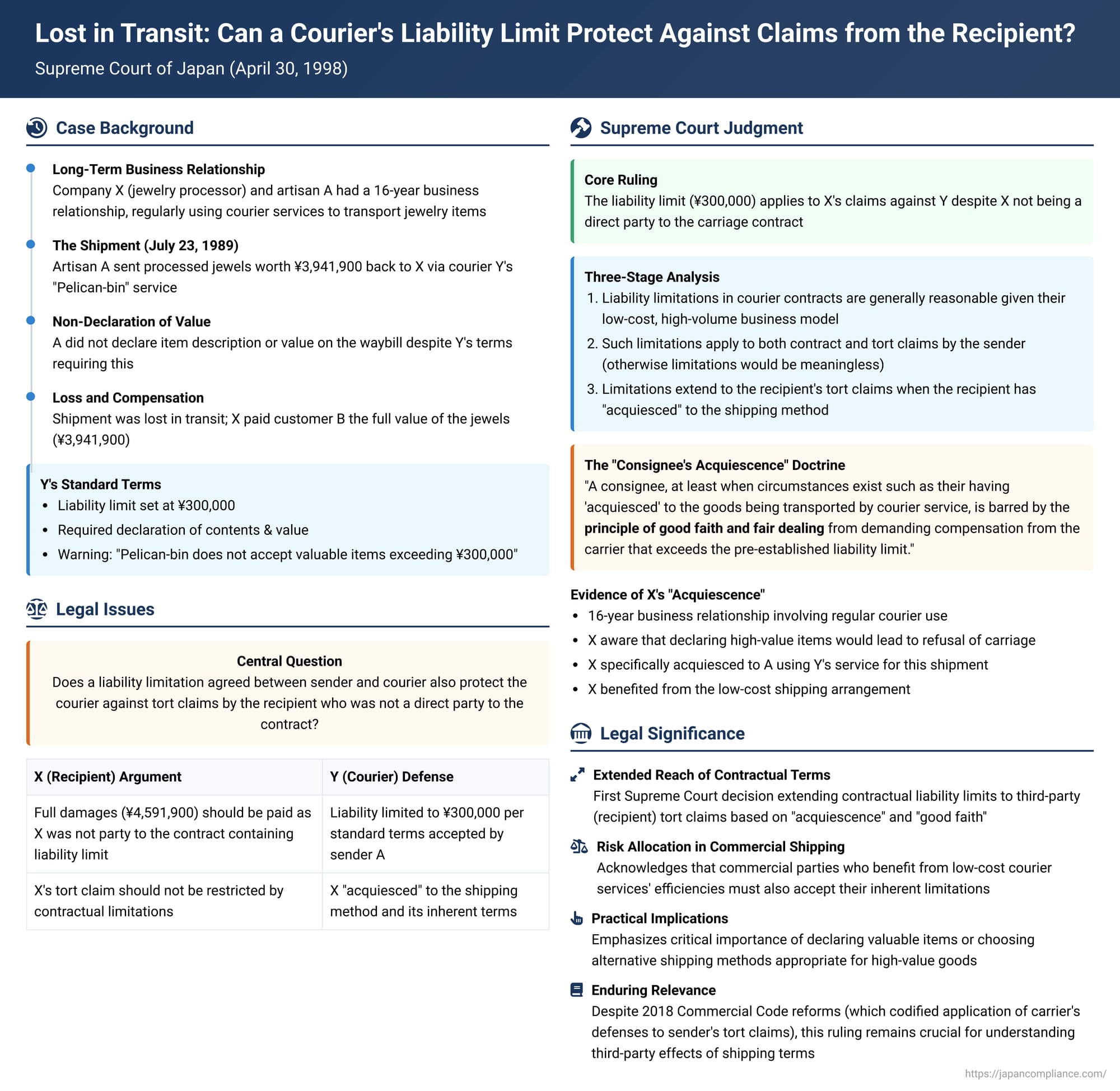

Courier services (宅配便 - takuhai-bin) are an integral part of modern commerce and daily life, prized for their convenience and speed in delivering a vast number of small parcels at relatively low cost. To maintain these low costs and manage risks associated with high-volume operations, courier companies typically include clauses in their contracts of carriage that limit their liability for lost or damaged goods, especially for high-value items that are not properly declared. A crucial legal question arises when a parcel is lost: how far does this contractual limitation of liability extend, particularly when the party claiming damages is the recipient (consignee) of the goods, who was not a direct signatory to the carriage contract between the sender and the courier? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this complex issue in a significant decision on April 30, 1998 (Heisei 6 (O) No. 799).

The Case of the Lost Jewels: A Chain of Commerce and a Courier's Terms

The plaintiff, X, was a company engaged in the sale and processing of precious metals. X had a long-standing business relationship with A, an individual artisan who had been X's exclusive subcontractor for jewelry processing for approximately 16 years. It was an established practice between X and A to use courier services for transporting valuable jewelry items back and forth. The judgment noted that X had "previously acquiesced" (容認していた - yōnin shite ita) to A using such services for these purposes.

The specific dispute arose when X subcontracted the processing of certain valuable jewels ("the Jewels"), owned by X's customer B, to A on July 6, 1989. After completing the processing, A arranged to send the Jewels back to X's premises in Tokyo. On July 23, 1989, A entrusted the parcel containing the processed Jewels ("the Shipment") to a local agent of the defendant courier company, Y, for delivery via Y's "Pelican-bin" courier service. This was reportedly the fourth occasion on which A had used Y's service to send jewels to X.

Y's courier service operated under standard terms and conditions, based on the then-prevailing Standard Courier Service Terms and Conditions stipulated by the Ministry of Transport. These terms included several important provisions:

- The sender was required to declare the description and value of the goods on the waybill. The carrier (Y) would then record its liability limit.

- Y's liability limit for loss or damage was set at ¥300,000.

- The waybill forms explicitly warned senders: "Please be sure to enter the value of your parcel. Pelican-bin does not accept valuable items exceeding ¥300,000. Even if such an item is shipped, we cannot be responsible for damages."

- Furthermore, a notice displayed at Y's agent (where A dropped off the parcel) stated that certain high-value items, including jewelry like diamonds, could be refused for carriage. It was also general industry practice for courier services to have similar liability limits (typically ¥200,000 to ¥400,000) and restrictions on accepting undeclared or high-value jewelry.

Despite these terms and warnings, when A dispatched the Shipment containing the valuable Jewels, A did not fill in the item description or value on Y's waybill. Y's agent, in turn, did not specifically prompt A about this omission or inquire about the contents. This pattern of non-declaration was reportedly similar to the previous three shipments A had made to X via Y's service.

Tragically, the Shipment containing the Jewels was lost somewhere in transit after being picked up by Y's agent and processed through Y's sorting terminals. The exact cause of the loss could not be determined. As a result of this loss, X was unable to return the processed Jewels to its customer B (the original owner). X subsequently compensated customer B for the full value of the Jewels, an amount totaling ¥3,941,900.

The Legal Battle: Can the Consignee Recover the Full Value from the Courier?

X then initiated a lawsuit against Y, the courier company, seeking to recover damages amounting to ¥4,591,900. This sum comprised the ¥3,941,900 X had paid to customer B, ¥150,000 for X's lost processing fees, and ¥500,000 for attorney's fees, plus interest.

The Tokyo High Court, as the appellate court below the Supreme Court, had limited X's recoverable damages to ¥300,000, the liability limit stipulated in Y's carriage contract with A. The High Court's reasoning was somewhat intricate: it acknowledged X's standing to sue (likely on the basis of having compensated the owner B and thus subrogating B's rights against Y under Article 422 of the Civil Code). While recognizing that, under the prevailing interpretation of the Commercial Code at the time, contractual limitations might not automatically apply to a sender's tort claim against a carrier, the High Court found that X could be "substantially identified" with the sender A due to their close and long-standing business relationship and the repeated use of courier services. It also found that Y had breached a good faith duty by not prompting A to declare the parcel's contents and value. Ultimately, however, it did not directly apply Y's liability limitation clause to X but instead used the ¥300,000 figure as a factor in determining the foreseeability of damages under general tort principles (Civil Code Article 416). Dissatisfied with this limitation, X appealed to the Supreme Court, seeking recovery of the full amount.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Extending the Shield of the Liability Limitation to the Acquiescing Consignee

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the ¥300,000 limit on Y's liability. The Court's judgment provided a clearer and more direct rationale for this conclusion, focusing on the nature of courier services, the purpose of liability limitations, and the conduct of the consignee, X.

The Supreme Court's reasoning unfolded in three key stages:

- Rationale for Liability Limits in Courier Services: The Court began by affirming the general reasonableness of liability limitation clauses in the context of courier services. It noted that such services offer significant public convenience by providing low-cost, high-volume, and rapid delivery of small parcels. To maintain these low fares and operational efficiency, it is understandable and acceptable for users to be subject to certain restrictions. Specifically, it is a rational business practice for courier operators to decline to carry items exceeding a certain declared value and to limit their liability for loss or damage to a predetermined amount (provided there is no willful misconduct or gross negligence on the carrier's part).

- Application of the Liability Limit to the Sender's Tort Claims: The Supreme Court then stated that such a liability limitation, agreed upon between the sender (A) and the carrier (Y), should apply not only to the carrier's liability for breach of contract towards the sender but also to any potential tort liability the carrier might have towards the sender. The Court reasoned that this interpretation aligns with the "rational intent of the parties." If the sender could simply circumvent the agreed liability limit by framing their claim in tort instead of contract, the entire purpose of the limitation would be nullified. This approach does not unduly prejudice the sender, the Court added, because standard courier terms (including Y's Article 25, Paragraph 6) typically stipulate that if the loss or damage is caused by the carrier's willful misconduct or gross negligence, the carrier must compensate for all resulting damages, thus overriding the ordinary limit.

- Extension of the Liability Limit to the Consignee's Tort Claims (The Core of the Decision): This was the most significant part of the judgment. The Supreme Court held that the liability limitation could indeed be extended to cover claims made by the consignee (X), even though X was not a direct party to the carriage contract between A and Y. The Court based this extension on the following considerations:Applying this to the specific facts involving X, the Supreme Court found compelling evidence of such acquiescence:Given these circumstances, the Supreme Court concluded that it would be contrary to the principle of good faith and fair dealing for X, having participated in and benefited from this established method of shipping with its known (or reasonably knowable) limitations and risks, to then demand compensation from Y far exceeding the ¥300,000 liability limit simply because a risk inherent in that system materialized. Thus, the High Court's decision to limit X's recoverable damages to ¥300,000 was affirmed as correct.

- The specific characteristics of courier services and the underlying purpose of establishing a liability limit.

- The fact that Y's terms and conditions (Article 25, Paragraph 3) also considered circumstances affecting the consignee when determining the amount of damages for loss or damage to goods.

- The Key Condition: The Consignee's "Acquiescence" (容認 - yōnin). The Court ruled that a consignee, "at least when circumstances exist such as their having 'acquiesced' to the goods being transported by courier service," is barred by the principle of good faith and fair dealing (信義則 - shingisoku) from demanding compensation from the carrier that exceeds the pre-established liability limit.

- X, the consignee, was aware that using Y's (or other similar) courier services for transporting valuable jewelry was effectively impossible if the true nature and high value of the items were accurately declared, as this would likely lead to refusal of carriage or require a different, more expensive shipping method.

- X and the sender A had a long-standing business relationship (16 years) involving the frequent use of courier services (up to 80 times a year from X to A alone) for sending jewelry back and forth.

- Regarding the specific lost Shipment, X had not merely recognized that it was being sent by courier but had, according to the facts, "acquiesced" to A using Y's particular courier service for this purpose.

- X, as a business, had arguably benefited from this practice of using low-cost courier services (facilitated by non-declaration or under-declaration) for transporting valuable items.

Analyzing the "Consignee's Acquiescence" Doctrine

The Supreme Court's introduction of the "consignee's acquiescence" as a condition for extending the carrier's liability limitation to a third-party consignee is a pivotal aspect of this ruling.

- Nature of Acquiescence: "Acquiescence" in this context appears to signify more than just passive knowledge that a courier service is being used. It implies a degree of understanding, acceptance, or even tacit approval of the shipping method, including its inherent terms and associated risks, particularly when demonstrated through a consistent course of conduct or specific agreement. In X's case, the long history of using couriers for valuable items, coupled with the understanding that full declarations would preclude this low-cost option, and X's specific consent to A using Y's service for the lost shipment, all pointed to a robust form of acquiescence.

- Good Faith as the Foundation: The decision to bind the consignee to the liability limit is explicitly rooted in the principle of good faith. This allows for a flexible, fact-sensitive analysis. It prevents a party (the consignee) who has, in essence, benefited from or participated in a system that relies on certain risk allocations (like liability limits for low-cost services) from then disavowing those allocations when a loss occurs.

- Distinction from Direct Contractual Privity: It's important to note that this ruling does not create a direct contractual relationship between the carrier (Y) and the consignee (X) for the purpose of enforcing the liability limitation clause as a contract term against X. Rather, the principle of good faith operates to prevent X from asserting a tort claim in a manner that would unfairly undermine the reasonable commercial arrangements and risk limitations established between the sender (A) and the carrier (Y)—arrangements of which X was aware and from which X derived benefits.

Implications for Commercial Shipments and Risk Allocation

This Supreme Court decision has several important implications for commercial shipping practices and the allocation of risk:

- It underscores the critical importance for senders to accurately declare the nature and value of goods entrusted to courier services, especially if they wish to secure coverage beyond the standard liability limits.

- It signals that consignees who are actively involved in or aware of and benefit from shipping practices that might involve under-declaration or the use of services with known limitations on high-value items may find their ability to recover the full extent of their losses curtailed.

- The judgment reinforces the general validity and enforceability of reasonable liability limitation clauses in standard courier service contracts, particularly when these clauses do not seek to exclude liability for the carrier's willful misconduct or gross negligence.

It is worth noting that subsequent reforms to Japan's Commercial Code (in 2018) have, to some extent, changed the landscape for disputes directly between the sender and the carrier by making many of the carrier's traditional defenses and limitations (such as those for undeclared high-value goods) generally applicable to tort claims brought by the sender as well. However, the principles articulated by the Supreme Court in this 1998 case concerning the extension of such limitations to third-party consignees based on "acquiescence" and "good faith" remain highly relevant for understanding the broader reach of contractual terms in multi-party commercial interactions.

Brief Note on the Consumer Context

This case involved commercial entities (X, the jewelry company, and A, its subcontractor). As such, the Consumer Contract Act (CCA) was not applicable. If a consumer were the sender or consignee in a similar scenario, the analysis might involve additional considerations under the CCA, particularly its provisions that restrict or nullify clauses that unduly limit a business's liability or unfairly disadvantage consumers (e.g., CCA Articles 8 and 10). The validity and enforceability of a liability limitation clause against a consumer would then be subject to these specific consumer protection standards, although the factual element of a consumer's knowing "acquiescence" to certain risks might still play a role in the overall assessment depending on the circumstances.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1998 ruling in the lost jewels case provides a nuanced framework for determining when a courier company's contractual limitation of liability can be invoked against a claim made by the consignee, a third party to the original carriage contract. By centering the analysis on the consignee's "acquiescence" to the method of shipment and its inherent terms, and grounding this in the overarching principle of good faith and fair dealing, the Court sought to achieve an equitable balance. It prevents a consignee who has knowingly benefited from a low-cost, potentially higher-risk shipping arrangement from later imposing full liability on the carrier when that inherent risk materializes, thereby upholding the reasonable commercial expectations and risk allocations that underpin such widely used services.