Survivor Pensions Are Not Lost Earnings: Japan’s Supreme Court on Wrongful‑Death Damages

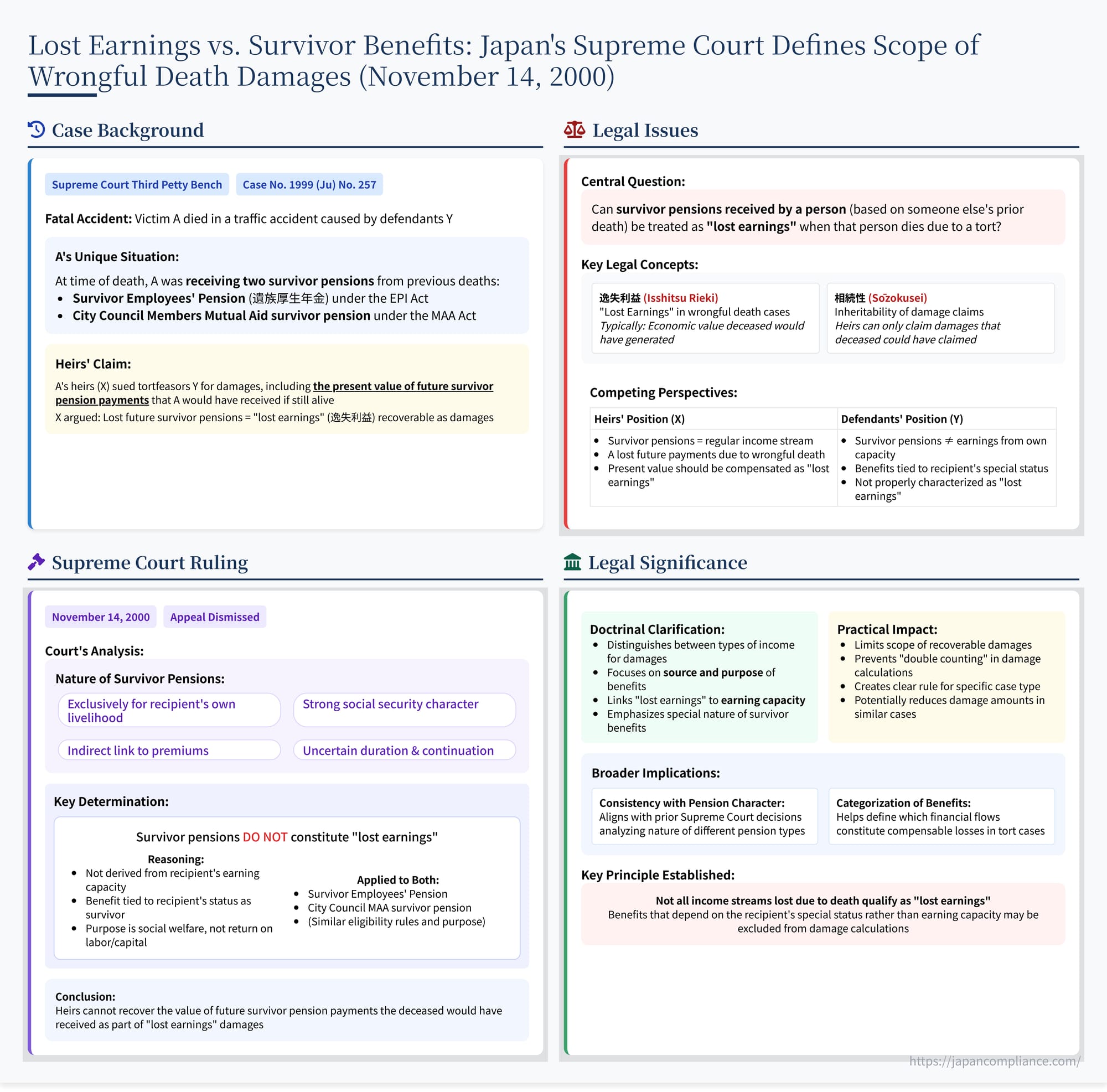

Japan’s Supreme Court (Nov 14 2000) ruled that survivor pensions are not part of a decedent’s lost earnings, sharpening the limits of wrongful‑death damages under Japanese tort law.

TL;DR

- The Supreme Court (Nov 14 2000) held that survivor pensions received by a victim cannot be treated as the victim’s own “lost earnings” in wrongful‑death claims.

- Such pensions exist solely to sustain the survivor’s livelihood and have only an indirect link to insurance premiums.

- Heirs may claim wages or retirement benefits based on the decedent’s own earning capacity, but not survivor benefits triggered by a third person’s death.

- The ruling limits recoverable damages and clarifies the economic‑loss calculus under Japanese tort law.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: A Fatal Accident and a Claim for Lost Survivor Pensions

- The Legal Issue: Are Survivor Pensions “Lost Earnings”?

- The Supreme Court’s Analysis (November 14 2000)

- Implications and Significance

- Conclusion

On November 14, 2000, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a concise but important judgment clarifying the scope of recoverable damages in wrongful death cases, specifically addressing whether survivor pensions received by the deceased can be counted as "lost earnings" (逸失利益 - isshitsu rieki) (Case No. 1999 (Ju) No. 257, "Damages Claim Case"). The Court distinguished survivor benefits, designed for the recipient's own livelihood, from income derived from earning capacity, ruling that the loss of future survivor pension payments due to the recipient's death is not recoverable as lost earnings by their heirs in a tort claim against the party responsible for the death. This decision helps delineate the types of economic losses considered compensable in wrongful death actions under Japanese law.

Note: The official Supreme Court judgment text for this case is quite brief. This analysis elaborates on the core reasoning presented within that text and its broader implications.

Factual Background: A Fatal Accident and a Claim for Lost Survivor Pensions

The case involved a claim for damages following a fatal traffic accident:

- The Accident and Victim: The victim, A, was killed in a traffic accident caused by the appellees, Y (the tortfeasors/defendants).

- A's Pension Status: Crucially, at the time of death, A was receiving two types of survivor pensions:

- A Survivor Employees' Pension (遺族厚生年金 - izoku kōsei nenkin) under the Employees' Pension Insurance Act (EPI Act). This pension is typically paid to the surviving dependents (like a spouse or child) of a deceased person who was covered by the Employees' Pension system. A was receiving this presumably due to the prior death of a spouse or other qualifying family member who had been insured under the EPI.

- A survivor pension from the City Council Members Mutual Aid Association (市議会議員共済会の共済給付金としての遺族年金 - shigikaigiin kyōsaikai no kyōsai kyūfukin to shite no izoku nenkin) under the provisions of the Local Public Employees, etc. Mutual Aid Association Act (MAA Act) and the association's bylaws. This likely arose from the prior death of a family member who had been a city council member.

- The Heirs' Claim: A's heirs, the appellants X, sued the tortfeasors Y for damages resulting from A's wrongful death. As part of their claim for A's economic losses, X argued that A's death caused the loss of the future stream of payments from both the Survivor Employees' Pension and the MAA survivor pension that A would have received over their remaining life expectancy. X contended that the present value of these lost future pension payments constituted "lost earnings" (isshitsu rieki) attributable to A and should be recoverable as damages by the heirs.

The Legal Issue: Are Survivor Pensions "Lost Earnings"?

The central legal question was whether survivor pensions, received by an individual based on the prior death of another person (like a spouse or parent), can be treated as part of the recipient's own "lost earnings" when the recipient themselves dies due to a tort.

In Japanese wrongful death cases, heirs can typically claim damages for the deceased's isshitsu rieki. This generally represents the economic value of what the deceased would have likely earned or produced through their own efforts or assets had they lived out their normal lifespan, minus their likely personal living expenses. It often involves calculating lost wages based on earning capacity. The question here was whether survivor pensions fit within this concept of income representing the deceased's own economic value or earning potential.

The lower appellate court (the High Court) had presumably rejected this part of the heirs' claim, leading to their appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Analysis (November 14, 2000)

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by X (the heirs), affirming the lower court's decision that the lost survivor pensions did not constitute recoverable lost earnings of the deceased, A. The Court analyzed the nature and purpose of each type of survivor pension A had been receiving.

1. Nature of the Survivor Employees' Pension (EPI Act):

The Court focused on the defining characteristics of the Survivor Employees' Pension under the EPI Act (Art. 58 et seq.):

- Beneficiary Criteria: It is paid only to specific categories of survivors (spouse, children, parents, etc.) who were financially dependent on the deceased insured person at the time of their death. Eligibility often further depends on factors like the survivor's age or disability status (except usually for widows).

- Purpose: Survivor's Livelihood: The structure and eligibility rules indicate that the pension's purpose is "exclusively for the maintenance of the recipient survivor's own livelihood" (専ら受給権者自身の生計の維持を目的とした給付 - moppara jukyūkensha jishin no seikei no iji o mokuteki to shita kyūfu). It is intended to provide economic support directly to the surviving dependent.

- Social Security Character & Indirect Link to Premiums: The recipient survivor typically has not paid premiums directly for this benefit. While funded by the overall EPI system (based on contributions by workers and employers, plus state subsidies), the connection (kenrensei - けん連性) between the benefit received by the survivor and premiums paid (either by the survivor or even the originally deceased insured person) is indirect. This highlights the pension's strong "social security character" (shakai hoshōteki seikaku - 社会保障的性格) rather than being a direct return on contributions or an earned entitlement of the survivor recipient in the same way as, for example, an Old-Age Employees' Pension based on one's own work history.

- Uncertainty of Duration: The right to receive the survivor pension is not guaranteed indefinitely. It terminates upon certain events related to the survivor's status, such as their own death, remarriage (for a spouse), adoption by someone other than a lineal relative (for a child), or reaching a certain age (for children/grandchildren). Since some of these terminating events (like marriage or adoption) can depend on the recipient's own decisions, the "continuation [of the right] is not necessarily certain" (sono sonzoku ga kanarazushimo kakujitsu na mono to iu koto mo dekinai).

Conclusion on EPI Survivor Pension: Considering these points – its purpose (recipient's livelihood), its social security nature with an indirect link to premiums, and the uncertainty of its duration – the Court concluded that the Survivor Employees' Pension is fundamentally a benefit intended to support the recipient survivor during their lifetime based on their status as a dependent survivor. Therefore, the potential future stream of these payments, which A happened to be receiving due to someone else's prior death, could not be considered as representing A's own lost earnings or earning capacity. Thus, its loss due to A's death caused by Y's tort was not compensable as A's lost earnings recoverable by A's heirs (X).

2. Nature of the City Council MAA Survivor Pension:

The Court then examined the survivor pension A received from the City Council Members Mutual Aid Association. It noted that the governing rules (under the MAA Act and the association's bylaws) regarding the scope of eligible survivors, grounds for termination of the right (disqualification events - shikken jiyū), etc., were similar to those for the Survivor Employees' Pension. Furthermore, the recipient survivor (A) did not contribute premiums or dues (kakekin oyobi tokubetsu kakekin) specifically for this survivor benefit.

Conclusion on MAA Survivor Pension: Based on these similarities, the Court concluded that the City Council MAA survivor pension shared the same essential purpose and character as the Survivor Employees' Pension – namely, providing livelihood support to the recipient survivor. Therefore, the reasoning applied to the EPI survivor pension held true here as well: the loss of future payments of this pension due to A's death did not constitute recoverable lost earnings for A.

Final Judgment: As both types of survivor pensions A was receiving were deemed not to constitute lost earnings, the lower court's judgment rejecting this part of the heirs' (X's) damages claim was correct. The Supreme Court therefore dismissed the appeal.

Implications and Significance

This 2000 Supreme Court decision provides crucial clarification on the calculation of lost earnings in Japanese wrongful death tort claims, particularly when the deceased was receiving survivor benefits.

- Distinction Between Income Types: The ruling highlights the critical legal distinction between different types of income or benefits received by a deceased person. While income derived from the deceased's own labor or capital (wages, business profits, potentially retirement pensions based on their own contributions and work history) might be considered lost earnings, benefits received solely based on their status as a survivor of another person are generally not.

- Focus on the Purpose and Nature of the Benefit: The Court's analysis emphasizes the purpose for which a benefit is granted. Survivor pensions, aimed specifically at maintaining the survivor's livelihood and possessing a strong social security character with an indirect link to contributions, are distinct from benefits earned through one's own economic activity or contributions.

- "Lost Earnings" Tied to Earning Capacity: The decision implicitly reinforces the idea that "lost earnings" (isshitsu rieki) in wrongful death cases are fundamentally linked to the deceased's own lost earning capacity or the economic value they generated, rather than simply any income stream they happened to be receiving. Survivor benefits do not reflect the recipient's earning capacity.

- Consistency with Prior Rulings on Pension Characteristics: The reasoning aligns with elements of previous Supreme Court decisions that analyzed the nature of different pension types (e.g., the Heisei 5 [1993] Grand Bench decision distinguishing between retirement and survivor pensions regarding homogeneity for son'eki sōsai, and the Heisei 11 [1999] decision distinguishing pension components based on contribution linkage and certainty). This case adds another layer by focusing on whether the benefit itself represents the deceased's own economic loss.

- Impact on Damages Calculation: This ruling prevents heirs from claiming the loss of survivor benefits received by the deceased as part of the deceased's own lost earnings damages. This likely limits the total recoverable amount in such specific cases compared to a scenario where all lost income streams were treated equally as lost earnings.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's November 14, 2000, judgment established that survivor pensions received by an individual under Japan's public pension systems (like the Employees' Pension Insurance Act or similar mutual aid schemes) are primarily intended for the recipient's own livelihood support and possess a strong social security character. They do not represent the recipient's earning capacity. Consequently, if such a recipient dies due to a tortious act, the loss of their future survivor pension payments cannot be claimed by their heirs as part of the deceased's "lost earnings" (isshitsu rieki) in a wrongful death damages lawsuit against the tortfeasor. This decision clarifies the scope of recoverable damages by distinguishing benefits based on survivorship status from economic losses stemming from the deceased's own earning potential.

- Japan Supreme Court 2017 Survivor‑Pension Case: Why Age Rules for Widowers Survived an Equality Challenge

- What Types of Damages Can Be Claimed and How Are They Calculated in Japanese Torts?

- Japan Supreme Court 2023 Pension‑Cut Ruling: Balancing Sustainability and Recipient Rights

- Judgments of the Supreme Court | Courts in Japan

- Pension Policy Overview | Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare