Loss of a Substantial Chance: Japan's Supreme Court on Compensation When Causation of Death is Uncertain

Date of Judgment: September 22, 2000 (Heisei 12)

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, 1997 (O) No. 42

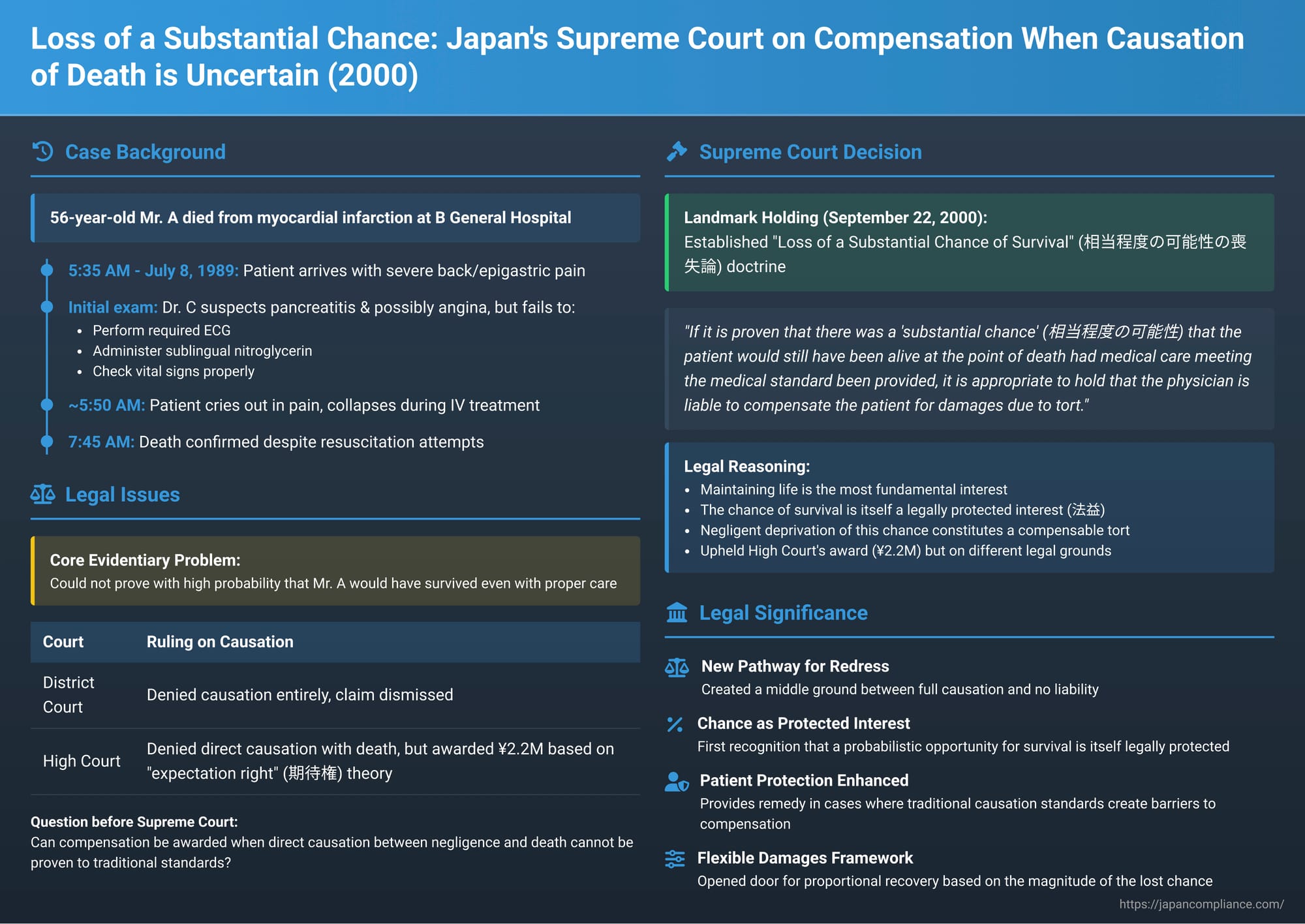

In a landmark decision issued on September 22, 2000, the Supreme Court of Japan formally recognized a basis for compensation in medical malpractice cases even when a direct causal link between a physician's negligence and a patient's death cannot be definitively proven under traditional standards. This judgment introduced and endorsed the doctrine of "loss of a substantial chance of survival," allowing for damages if a physician's negligence deprived a patient of a significant possibility of living, thereby acknowledging a new category of legally protected interest.

Factual Background: A Sudden Illness and Missed Diagnostic Opportunities

The case involved Mr. A, a 56-year-old man, who experienced a sudden onset of severe back pain in the early morning hours of July 8, 1989.

- Emergency Visit: After the pain recurred, Mr. A was taken by his son to B General Hospital, operated by defendant Y. They arrived around 5:35 AM.

- Initial Examination by Dr. C: Mr. A complained of upper back pain and epigastric (upper central abdominal) pain. Dr. C, the physician on duty, conducted a physical examination. While tenderness was noted in the epigastric region upon palpation, chest auscultation reportedly revealed no abnormal findings such as heart murmurs or arrhythmias. Mr. A informed Dr. C that he had experienced similar pain seven or eight years prior, which had been diagnosed as a ureteral stone. Dr. C, considering the nature of the pain, was skeptical of ureteral stones but ordered a urine test as a precaution, which came back negative for blood. Based on the symptoms, their location, and progression, Dr. C formed a primary suspicion of acute pancreatitis and a secondary suspicion of angina pectoris.

- Treatment Initiated Without Cardiac Evaluation: Dr. C then instructed a nurse to administer an intramuscular injection of a painkiller. Following this, Mr. A was moved to an adjacent room for an intravenous (IV) drip containing medication for acute pancreatitis. Critically, Dr. C initiated this IV treatment without first performing an electrocardiogram (ECG) or administering sublingual nitroglycerin, which were standard initial diagnostic steps for a patient presenting with symptoms suspicious of a cardiac condition like angina or myocardial infarction. The time from the start of the examination to Mr. A being moved for the IV drip was about ten minutes.

- Sudden Deterioration and Death: Approximately five minutes after the IV drip was started (making it about 15 minutes since arrival at the hospital and start of consultation), Mr. A suddenly cried out, "It hurts, it hurts!" He grimaced, writhed in pain, experienced a large convulsive movement, and then immediately fell into what appeared to be a deep, snoring sleep. His son alerted Dr. C, who rushed from the examination room. Dr. C attempted to rouse Mr. A, but his breathing soon stopped. Although his pulse was initially palpable (though very weak), Dr. C began external cardiac massage and other resuscitation efforts. Around 6:00 AM, Mr. A was moved to the hospital's intensive care unit, where other physicians joined the resuscitation attempts. Despite these efforts, Mr. A's death was confirmed at approximately 7:45 AM.

- Cause of Death and Identified Negligence: It was later determined that Mr. A had suffered an angina attack at home, which progressed to an acute myocardial infarction (heart attack) en route to or at the hospital. At the time of Dr. C's examination, the myocardial infarction was likely already in an advanced state. The sudden deterioration during the IV drip was attributed to a fatal arrhythmia.

The medical standard of care at the time for a patient presenting with symptoms like Mr. A's (back and epigastric pain) required physicians to first rule out urgent thoracic conditions. This involved taking a detailed history, measuring vital signs (blood pressure, pulse, temperature), and, if cardiac issues like angina or myocardial infarction were suspected, administering sublingual nitroglycerin while promptly performing an ECG to assess for arrhythmias and signs of ischemia. If myocardial infarction was confirmed, immediate measures such as securing IV access and administering oxygen and anti-arrhythmic drugs (like lidocaine if indicated) were necessary.

Dr. C, however, performed only palpation and auscultation. He failed to inquire about a history of thoracic disease, measure vital signs, or perform an ECG. Despite suspecting angina, he did not administer nitroglycerin. These omissions were deemed a failure to perform the basic duties required in the initial treatment of a patient with potential cardiac disease.

Legal Proceedings: From Denial of Causation to "Loss of Expectation Right"

Mr. A's surviving family members (X et al.) filed a lawsuit against Y, the operator of B General Hospital, seeking damages of over 69 million yen for Mr. A's wrongful death, including claims for lost income.

- First Instance (Tokyo District Court): The trial court dismissed the plaintiffs' claim. It found that a causal relationship between Dr. C's acts or omissions and Mr. A's death had not been proven.

- High Court (Tokyo High Court): The High Court also denied that a direct causal link between Dr. C's negligence and Mr. A's death was established (meaning it could not be proven with a high degree of probability that Mr. A would have survived if Dr. C had acted appropriately).

- However, the High Court adopted a different legal theory to find liability. It held that Dr. C's negligence had infringed Mr. A's "expectation right" (期待権 - kitaiken)—essentially, his right to expect and receive appropriate medical care according to the prevailing medical standards.

- The High Court stated that Mr. A was "unjustly deprived of the opportunity to receive appropriate medical treatment" due to Dr. C's failures.

- Based on this infringement of Mr. A's expectation right, the High Court ordered Y (the hospital operator) to pay 2.2 million yen as consolation money (慰謝料 - isharyō) for the mental suffering caused.

The defendant, Y, appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court, likely challenging the finding of liability based on this "expectation right" theory, especially since direct causation with death had been negated.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision (September 22, 2000)

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's award of compensation to Mr. A's heirs. However, the Supreme Court did so by establishing a new legal foundation for such awards, distinct from the "expectation right" theory relied upon by the High Court. This new foundation is now widely known as the "loss of a substantial chance of survival" doctrine.

The "Substantial Chance of Survival" Doctrine:

The Court articulated the core of this new doctrine as follows:

"In a case where a physician's medical act, due to their negligence, did not meet the medical standard of the time when treating a patient who subsequently died from an illness, and although a causal relationship between the said medical act (or omission) and the patient's death is not proven [to the traditional standard of high probability], if it is proven that there was a 'substantial chance' (相当程度の可能性 - sōtō teido no kanōsei) that the patient would still have been alive at the point of death had medical care meeting the medical standard been provided, it is appropriate to hold that the physician is liable to compensate the patient for damages due to tort."

Rationale for Protecting This "Chance":

The Supreme Court provided a clear justification for recognizing this "chance" as a legally protectable interest:

"This is because maintaining life is the most fundamental interest for a person, and the aforementioned chance [of survival] is an interest that ought to be protected by law. It can be said that the patient's legal interest (法益 - hōeki) was infringed by the physician's failure, due to negligence, to provide medical care meeting the medical standard."

Affirming the High Court's Conclusion on New Legal Grounds:

While the High Court had based its award on the infringement of an "expectation right," the Supreme Court stated:

"The original instance court [High Court], based on a legal interpretation to the same effect as above [i.e., recognizing liability even if causation of death itself was not proven, where proper care offered a significant chance], recognized the establishment of Dr. C's tort and held that Y, as Dr. C's employer, was obliged to pay consolation money for the mental suffering Mr. A incurred due to that tort. This judgment by the original instance court can be affirmed as just."

In essence, the Supreme Court found that the High Court had reached the correct outcome (awarding compensation) but reframed the legal basis for that outcome as the infringement of the patient's "substantial chance of survival" due to the physician's negligence.

Analysis and Implications: A New Avenue for Patient Redress

The Supreme Court's decision in this 2000 case is a watershed moment in Japanese medical malpractice law for several key reasons:

- Formal Establishment of the "Loss of a Substantial Chance of Survival" Doctrine: This judgment is recognized as the first clear instance where the Japanese Supreme Court explicitly endorsed and articulated the "loss of a substantial chance of survival" as a distinct basis for compensation in medical malpractice cases resulting in death.

- Addressing the "Causation Gap": The doctrine was developed to address the significant challenge faced by plaintiffs in proving, with a high degree of probability (the standard for full causation of death as established in the 1975 Lumbar Puncture Case), that the physician's negligence was the direct cause of the patient's death. In many medical scenarios, especially with complex or rapidly progressing illnesses, it can be very difficult to prove that the patient definitively would have survived if not for the negligence. The "substantial chance" doctrine allows for recovery if negligence deprived the patient of a significant possibility of survival, even if survival was not a certainty.

- "Substantial Chance" as a Legally Protected Interest: The Court's explicit recognition of the "chance of survival" as a legal interest (hōeki) worthy of protection under tort law was a critical conceptual step. The negligent infringement of this chance became, in itself, a compensable harm.

- Nature and Quantum of Damages: Compensation under this doctrine is typically for the loss of the chance itself. This often leads to damages that are less than what would be awarded in a successful full wrongful death claim (where lost income, full consolation for death, etc., are calculated). In this specific case, the High Court had awarded consolation money for the "loss of opportunity for appropriate treatment," and the Supreme Court upheld this quantum under its "loss of substantial chance" framework. The precise method for quantifying damages for a lost chance has been a subject of ongoing discussion in subsequent jurisprudence.

- Defining "Substantial": The term "substantial chance" (or "considerable degree of possibility") is not mathematically quantified in the judgment. It implies a chance that is more than merely speculative or remote but may be less than a "more likely than not" probability (i.e., >50%). The exact threshold remains a matter for case-by-case determination based on expert testimony and the specific facts.

- Evolution from Prior Legal Theories: The PDF commentary accompanying this case insightfully traces the development of legal thinking in Japan aimed at addressing the difficulties of proving medical causation. Earlier lower court attempts included theories like "infringement of life-prolonging interest" or, as seen in this case's High Court ruling, "infringement of expectation right." The Supreme Court's "substantial chance" doctrine provided a more robust and authoritative legal foundation.

- Relationship with Other Causation Principles: This doctrine operates alongside, rather than replaces, the traditional standard for proving full causation of death (as per the 1975 Lumbar Puncture Case and the 1999 Liver Cancer Case). The "loss of chance" doctrine comes into play when the higher threshold for proving full causation cannot be met, but evidence still shows that negligence significantly diminished the patient's prospects for survival. Legal scholars continue to debate the precise interplay and theoretical underpinnings of these different approaches to causation and harm in medical law.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's September 22, 2000, judgment marks a pivotal advancement in Japanese medical malpractice law. By establishing the "loss of a substantial chance of survival" as a compensable harm, the Court provided an essential avenue for redress to patients and their families in situations where medical negligence demonstrably reduced a patient's prospects for life, even if it could not be proven with certainty that the negligence directly caused the death. This doctrine reflects a judicial effort to achieve a fairer balance in medical litigation, acknowledging the inherent uncertainties of medical outcomes while holding healthcare providers accountable for negligent acts that deprive patients of significant opportunities for survival. It remains a crucial legal principle in navigating the complex interface of medicine, law, and the pursuit of justice.