Long Vacations vs. Business Needs: Japan's Supreme Court on Changing Leave Timing (June 23, 1992)

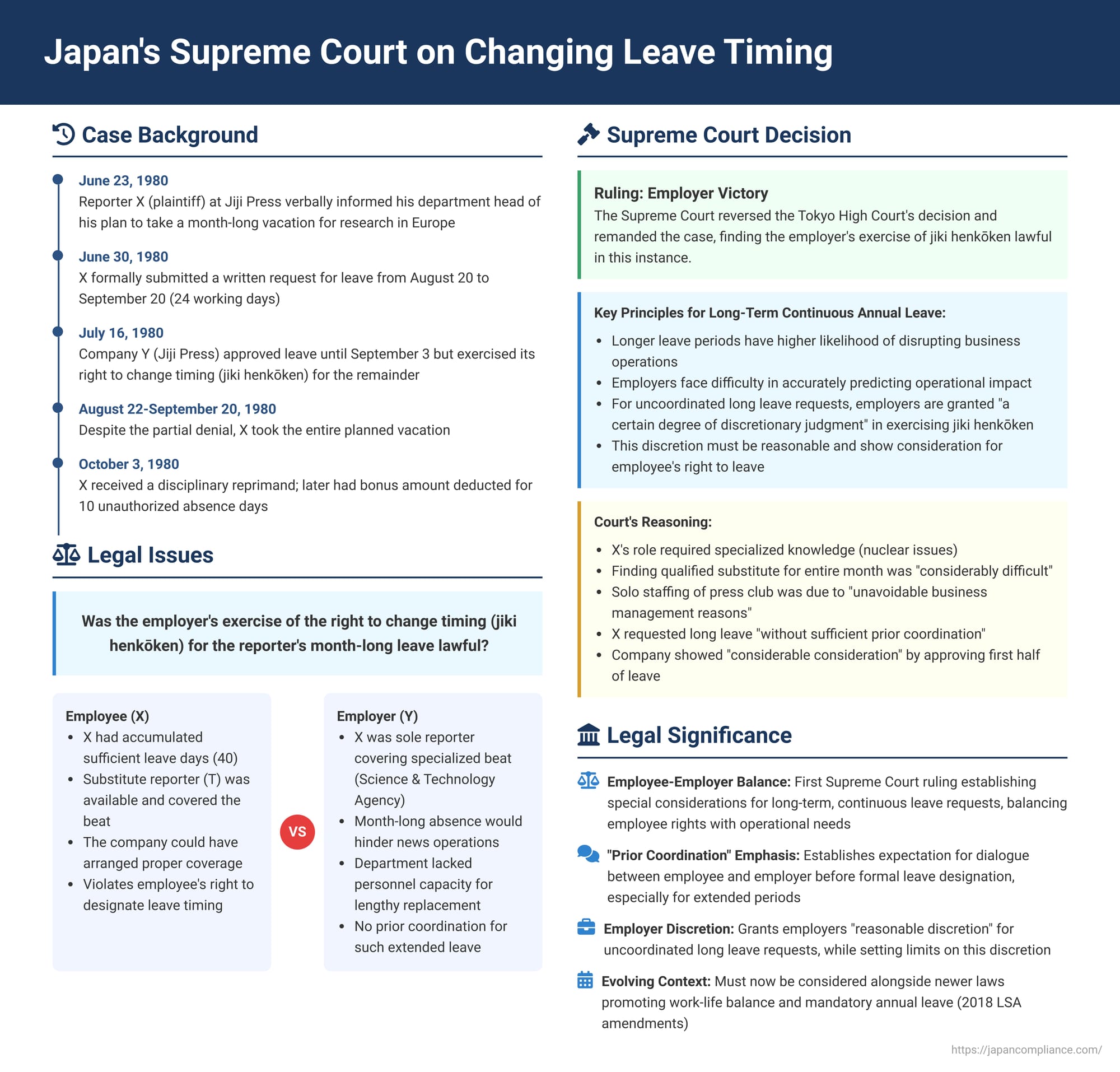

On June 23, 1992, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment in a case concerning a news reporter's request for a month-long period of paid annual leave. This case, often dubbed the "Jiji Press Case" (時事通信社事件) by commentators and sometimes referred to as the "Vacances Trial", critically examined the extent of an employer's right to change the timing (時季変更権 - jiki henkōken) of such long-term, continuous leave, particularly when the employee holds a specialized role with sole responsibility for their beat. The ruling provides insight into the balance between an employee's right to take extended leave and an employer's operational necessities, granting employers a degree of discretion under specific circumstances.

A Reporter's Request for Extended Leave

The plaintiff, X, was an experienced reporter employed by Company Y, a news agency. From April 1978, X worked in the social affairs department of Company Y's head office. By the time of the events in question (1980), X was solely responsible for covering the press club at the Science and Technology Agency (a government body at the time). Previously, until March 1979, this beat had been handled by a two-person team. X's area of coverage was extensive, encompassing a wide range of science and technology topics, with a significant emphasis on nuclear energy issues.

The dispute arose from the following sequence of events:

- Leave Request: On June 23, 1980, X verbally informed Department Head A of the social affairs department of an intention to take approximately one month of paid annual leave, starting around August 20, 1980. X stated the purpose of this leave was to travel to Europe to conduct research and reporting on nuclear power issues there. On June 30, 1980, X formally submitted a written leave and absence request, specifying the period from August 20 to September 20, 1980, which amounted to 24 working days of paid annual leave. At that time, X was entitled to 40 days of annual leave, including carry-over from the previous year.

- Company Y's Response: Department Head A responded by asking X to split the requested one-month leave into two separate two-week blocks. Subsequently, on July 16, 1980, Company Y formally notified X that leave from August 20 to September 3 was approved. However, for the remainder of the requested period, specifically for working days falling between September 4 and September 20, Company Y exercised its statutory right to change the timing of the leave (jiki henkōken). (The start of this modified period would adjust if X delayed the initial leave start date).

- Reasons for Changing Timing: Department Head A provided two main reasons for this decision:

- X was the sole permanently assigned reporter covering the Science and Technology Agency press club. An absence of such a specialized reporter for an entire month could potentially hinder news gathering and reporting activities.

- The department lacked the personnel capacity to arrange a suitable replacement reporter for such an extended period.

- Unresolved Discussions and Departure: Collective bargaining sessions between X's labor union and Company Y failed to yield a compromise on the leave issue. Despite the company's exercise of its right to change timing for the latter part of the leave, X proceeded with the original travel plans, departing on August 22 (slightly later than the initial August 20 request) and remaining off work until September 20, 1980. Before departing, X did submit a document to Department Head A, stating an intention to cut the trip short and return if any major incident, such as a nuclear power plant accident (a concern for the company), occurred, and provided contact information (though this was general contact information for Japanese diplomatic missions abroad).

- Disciplinary Action and Bonus Deduction: As a result of X's absence during the period for which the company had exercised its right to change timing (specifically, 10 working days between September 6 and September 20, after accounting for X's slightly delayed departure), Company Y took disciplinary action. On October 3, 1980, X was given a formal reprimand (けん責処分 - kenseki shobun) for violating a work order by not working during this period. Furthermore, when year-end bonuses were paid in December 1980, Company Y deducted an amount from X's bonus equivalent to the pay for these 10 days of absence.

- Substitute Coverage During X's Absence: During X's absence from August 22 to September 20, a colleague, Reporter T (who worked as a desk assistant in the social affairs department, also covered the Meteorological Agency press club, and had prior experience at the Science and Technology press club), covered X's beat. Reporter T produced 15 articles related to science and technology during this period.

X subsequently filed a lawsuit seeking invalidation of the disciplinary reprimand, payment of the deducted bonus amount, and solatium for emotional distress.

The Lower Courts' Conflicting Decisions

The case saw differing outcomes in the lower courts:

- Tokyo District Court (First Instance): Dismissed all of X's claims, siding with Company Y.

- Tokyo High Court (Appeal): Overturned the District Court's decision, ruling in favor of X. The High Court found the disciplinary action invalid and awarded partial damages. Its reasoning included the assessment that, even considering Company Y's staffing constraints and the specialized nature of X's duties, it was not "extremely difficult" for the company to arrange a substitute for X.

Company Y then appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: A Degree of Employer Discretion

The Supreme Court reversed the Tokyo High Court's decision (which had favored the employee) and remanded the case for further consideration. The Supreme Court's judgment established important principles regarding an employer's exercise of the right to change timing for long-term, continuous annual leave requests.

I. General Principles for Long-Term Continuous Annual Leave

The Court outlined several general considerations:

- Increased Likelihood of Disruption and Need for Coordination: "When a worker attempts to take long-term, continuous paid annual leave, the longer the period, the higher the likelihood that it will hinder the normal operation of the business (e.g., increased difficulty in securing substitute workers), and it usually becomes necessary to coordinate in advance with the employer's business plans and other workers' leave schedules".

- Employer's Predictive Challenge and Discretionary Judgment: "Moreover, for the employer, it is difficult at the time of the worker's timing designation to accurately predict various circumstances relevant to maintaining the normal operation of business activities, such as the anticipated workload at the worker's assigned workplace during the long leave period, the possibility of securing substitute workers, and the number of other workers designating leave for the same period. The employer has to make a judgment based on probabilities regarding the existence and extent of disruption the worker's leave might cause to business operations". In light of this, "if a worker, without undergoing such coordination, specifies the start and end dates for a long and continuous period of annual leave within their entitled days, the employer must be allowed a certain degree of discretionary judgment in exercising the right to change the timing with respect to what kind of disruption the said leave would cause to business operations and what extent of modification or change to the timing or duration of the leave is necessary".

- Requirement of Reasonableness and Due Consideration: "Of course, this discretionary judgment concerning the employer's exercise of the right to change timing must be reasonable and align with the purpose of Article 39 of the Labor Standards Act, which guarantees the worker's right to paid annual leave. If this discretionary judgment is found to be contrary to the purpose of said Article, such as lacking due consideration by the employer for enabling the worker to take leave according to the circumstances, it should be judged as lacking the requirements for exercising the right to change timing as prescribed in the proviso of Paragraph 3 [now Paragraph 5] of said Article, and its exercise should be deemed unlawful".

II. Application to the Specific Facts of the Case

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court found Company Y's exercise of its right to change timing to be lawful in this instance:

- Difficulty in Securing a Qualified Substitute: X's duties as the sole reporter for the Science and Technology press club required a certain level of specialized knowledge, particularly concerning nuclear issues, and X had, by that time, acquired considerable expertise. The Court concluded that finding a reporter within Company Y's social affairs department who could seamlessly cover X's specialized duties without disruption for an extended period was "considerably difficult".

- Justification for Solo Staffing: The Supreme Court acknowledged that Company Y's practice of having solo reporters or reporters covering multiple beats in its social affairs department was a result of "unavoidable business management reasons". Company Y's primary business focus was on specialized news services for government agencies and corporations, leading to a leaner staffing model for general news services (which included the social affairs department) compared to other major news organizations. Therefore, X's solo assignment was not deemed inherently improper solely from the perspective of facilitating annual leave.

- Lack of Sufficient Prior Coordination by the Employee: X had requested a long, continuous leave period of approximately one month without engaging in "sufficient prior coordination" with Company Y regarding the timing and duration.

- Employer's "Considerable Consideration": Department Head A exercised the right to change timing only for the latter portion of the requested leave (from September 6 onwards), thereby still approving a significant initial period of leave (August 22 to September 5, effectively two weeks). The Supreme Court viewed this as Company Y showing "considerable consideration" for X's leave request under the prevailing circumstances.

Considering these points, the Supreme Court concluded: "Under the circumstances at the time in July and August 1980, where it was difficult to secure a reporter within the social affairs department who could, without disruption, substitute for X's duties requiring specialized knowledge, Company Y's exercise of its right to change the timing for a portion of X's leave, deeming that granting the full long-term annual leave as designated by X would 'hinder the normal operation of the business,' cannot be said to be an unreasonable discretionary judgment contrary to the purpose of Article 39 of the Labor Standards Act, and should be considered as fulfilling the requirements of the proviso to Paragraph 3 [now Paragraph 5] of said Article".

In-Depth Analysis and Lasting Implications

This "Vacances Trial" was a landmark because it was one of the first high-profile cases to directly address the issue of long-term, continuous paid annual leave, a practice less common in Japan compared to shorter, often fragmented, leave periods.

- The Emphasis on "Prior Coordination": The judgment's stress on the need for "prior coordination" for long leave requests is significant. This resonates with earlier Supreme Court jurisprudence (like the 1973 Shiraishi Forestry Office Case) which, while establishing the employee's fundamental right to designate leave timing, also hinted at the desirability of planned and coordinated approaches, especially for extended leave periods. The "coordination" envisaged seems to be a dialogue between employer and employee before a formal, unalterable designation is made, to align the employee's wishes with operational realities. However, the precise legal nature and requirements of this "coordination," and the consequences if it fails, remain areas of discussion.

- Employer Discretion and its Limits: The Court's recognition of "a certain degree of discretionary judgment" for employers when faced with uncoordinated long leave requests is a key takeaway. This discretion is granted due to the inherent difficulty for employers in precisely predicting the operational impact (disruption, need for substitutes) of such leave at the moment of request. However, this discretion is not absolute; it must be "reasonable" and demonstrate "due consideration" for the employee's right to take leave. The commentary suggests that because the Court bases this discretion on a "probability-based judgment" by the employer, the employer's right to change timing might be interpreted quite broadly in practice when long, uncoordinated leave is requested.

- Academic and Critical Perspectives: The judgment has elicited varied reactions. Some scholars show understanding for the Supreme Court's approach, given the practical challenges of long leave. Others raise concerns, arguing against:

- Treating long leave differently from short leave in principle.

- Granting employers discretionary judgment over what is fundamentally an employee's right.

- The potential negative impact on the overall goal of full annual leave utilization.

- Divergence on Factual Assessment: There's a notable contrast between the Supreme Court's and the High Court's assessment of the facts, particularly regarding the difficulty of finding a substitute for X. The High Court found substitution not "extremely difficult," noting that Reporter T did, in fact, cover X's beat. The Supreme Court, while acknowledging Reporter T's coverage, emphasized the difficulty of securing a long-term substitute for X's specialized role from within the existing social affairs department staff. The commentary questions whether the Supreme Court adequately justified overturning the High Court's factual assessment here, and whether it gave sufficient weight to the fact that X's beat was previously a two-person assignment. The argument is that if solo staffing (a management decision) makes leave-taking difficult, the employer might bear a greater responsibility to find solutions beyond simply curtailing the employee's leave.

Modern Context and Evolving Norms

Since this 1992 judgment, Japanese labor law and societal norms around work-life balance have continued to evolve.

- The Labor Contract Act (enacted later) includes provisions concerning work-life balance (Article 3, Paragraph 3).

- More significantly, amendments to the Labor Standards Act in 2018 (effective 2019) now mandate that employers ensure employees entitled to 10 or more days of annual leave take at least 5 of those days within a year. This legislation includes provisions requiring employers to consult with employees about the timing of these mandated leave days and to make efforts to respect their opinions.

These developments signal a stronger legislative push towards ensuring employees actually take their entitled leave. Future interpretations of disputes involving long-term leave requests will likely need to consider these evolving legal and social expectations favoring better work-life balance and fuller utilization of annual leave.

Conclusion: A Qualified Nod to Employer Discretion

The Jiji Press Case underscores that while employees have a statutory right to designate the timing of their paid annual leave, this right is not entirely unfettered when it comes to requests for long and continuous periods taken without substantial prior coordination with the employer. In such situations, the Supreme Court grants employers a degree of reasonable discretion to change the timing of the leave if there is a demonstrable likelihood of significant disruption to the normal operation of the business. This discretion, however, must be exercised with genuine consideration for the employee's need for leave. The case highlights the delicate balance employers must strike between respecting employees' rights to extended rest and ensuring business continuity, particularly in roles requiring specialized skills or where staffing is lean. It also implicitly encourages proactive dialogue and planning between employees and employers for longer leave periods to avoid such disputes.