Long-Term Medical Leave & Dismissal: Japan's Supreme Court on Workers' Comp and Termination Compensation (June 8, 2015)

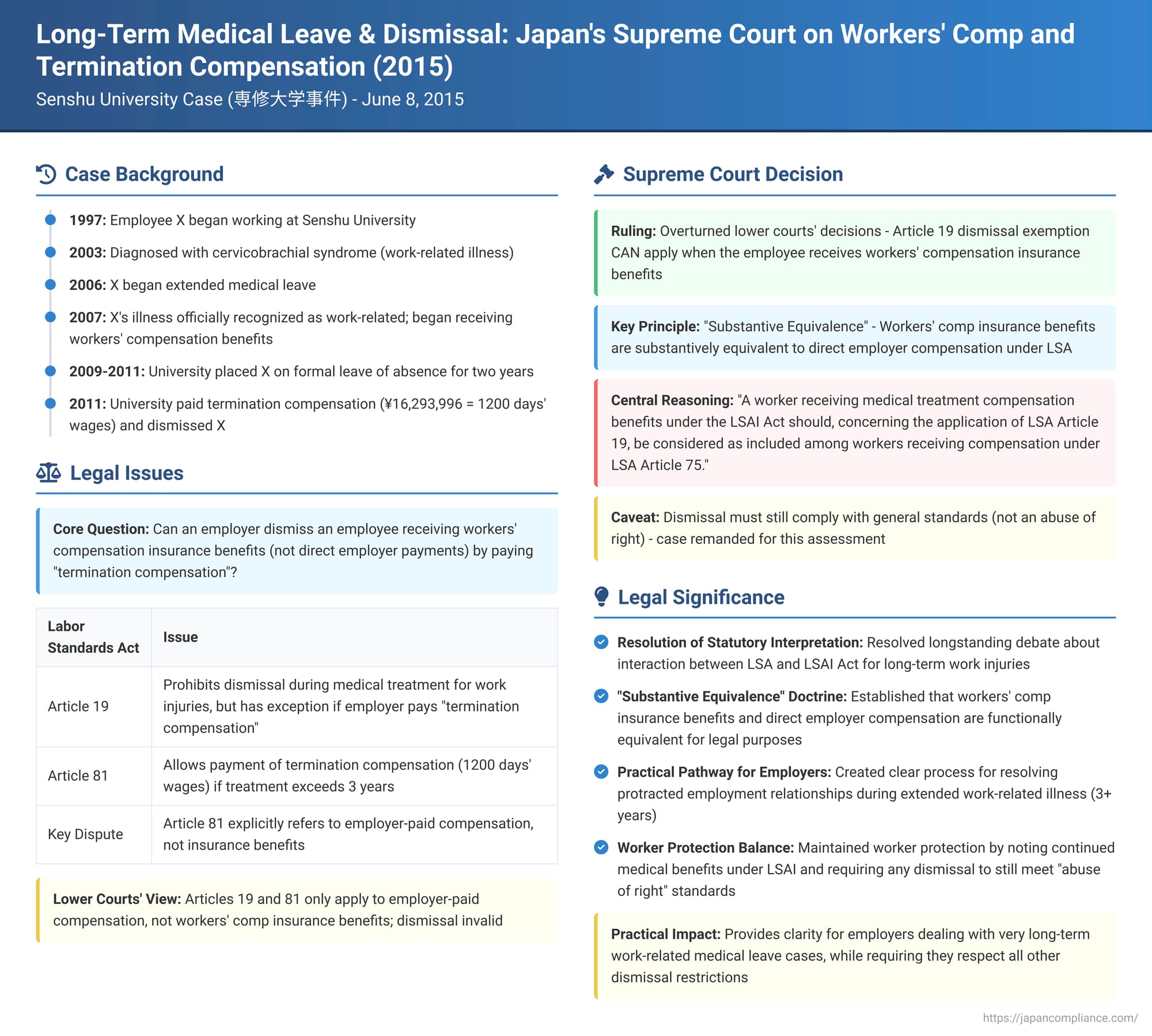

On June 8, 2015, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment in a case often referred to as the "Senshu University Case" by legal commentators. This ruling addressed a critical question at the intersection of Japan's Labor Standards Act (LSA) and the Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act (LSAI Act): Can an employer dismiss an employee who is on extended medical leave for a work-related illness and receiving benefits under the LSAI Act, by paying a "termination compensation" (打切補償 - uchikiri hoshō) as stipulated in LSA Article 81, thereby lifting the dismissal restrictions otherwise imposed by LSA Article 19? The Court's affirmative answer, based on the "substantive equivalence" of LSAI benefits and direct employer compensation, has important implications for long-term employment relationships affected by work-related health issues.

A Protracted Absence Due to Work-Related Illness

The plaintiff, X, had been employed as a university staff member by Defendant Y, an incorporated educational institution (hereafter "University S"), since April 1997.

- In March 2003, X was diagnosed with cervicobrachial syndrome (頸肩腕症候群 - keikenwan shōkōgun), a condition affecting the neck, shoulders, and arms (the "Illness").

- Following this diagnosis, X began to have repeated absences from work starting in April 2003, and from January 2006, X commenced a period of long-term absence.

- In November 2007, Labor Standards Inspection Office Director A officially recognized X's Illness as work-related. Consequently, a decision was made to grant X medical treatment compensation benefits (療養補償給付 - ryōyō hoshō kyūfu) and work absence compensation benefits (休業補償給付 - kyūgyō hoshō kyūfu) under the LSAI Act.

- By January 2009, X's continuous absence from work (since January 2006) had exceeded three years. As X remained unable to work due to the Illness, University S, in accordance with its internal regulations, placed X on a formal leave of absence for a period of two years, starting from January 2009.

- This two-year leave period expired in January 2011. University S, deeming X's return to work impossible, took action in October 2011. It paid X a sum equivalent to 1200 days of X's average wage (amounting to 16,293,996 yen) as "termination compensation" (打切補償 - uchikiri hoshō), pursuant to Article 9 of its internal employee compensation regulations (which mirrored LSA Article 81). Following this payment, University S dismissed X. University S also made additional ex-gratia payments to X totaling 18,960,506 yen.

Initially, University S filed a lawsuit seeking a declaration that X was no longer its employee. X responded with a counterclaim, seeking confirmation of X's continued employment status and arguing that the dismissal was invalid. University S subsequently withdrew its original suit, and the legal battle proceeded based on X's counterclaim.

The Core Legal Question: Lifting Dismissal Restrictions

The central legal issue revolved around LSA Article 19, Paragraph 1. This provision generally prohibits an employer from dismissing an employee during a period of medical leave taken for a work-related injury or illness, and for 30 days thereafter. However, a proviso to this article states that this dismissal restriction does not apply if the employer pays "termination compensation" as stipulated in LSA Article 81.

LSA Article 81, in turn, states that if an employee receiving medical compensation under LSA Article 75 (which obliges the employer to directly provide necessary medical treatment compensation) is not cured after three years from the commencement of medical treatment, the employer can pay termination compensation (1200 days' average wage) and thereby end its ongoing compensation obligations.

The question was: Does this exception (lifting the dismissal restriction via termination compensation) apply when the employee, like X, is receiving medical treatment benefits under the LSAI Act (specifically, LSAI Act Article 12-8, Paragraph 1, Item 1 for medical treatment compensation benefits) rather than directly from the employer under LSA Article 75?

Both the Tokyo District Court (first instance) and the Tokyo High Court (on appeal) ruled in favor of X, finding the dismissal invalid. They adopted a strict textual interpretation, reasoning that LSA Article 81 explicitly refers to workers receiving compensation under LSA Article 75. Since X was receiving LSAI Act benefits, they concluded that the conditions of LSA Article 81 were not met, and therefore the dismissal restriction under LSA Article 19, Paragraph 1 remained in force, rendering X's dismissal unlawful. University S appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: "Substantive Equivalence"

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further consideration, finding that the dismissal restriction could indeed be lifted under these circumstances.

I. The Interplay Between LSA Compensation and LSAI Act Benefits

The Court began by analyzing the relationship between the employer's direct compensation duties under the LSA and the benefits provided by the LSAI Act:

- It reaffirmed a long-standing principle (citing a 1977 Supreme Court precedent, the Sankyo Motorcar Case): "Considering the purpose of the LSAI Act and the content of provisions in the Labor Standards Act and the LSAI Act concerning compensation for work-related disasters, the workers' accident compensation insurance system... is a system where, premised on the existence of the employer's disaster compensation obligation under the Labor Standards Act, insurance benefits are provided as an alternative to employer's disaster compensation, in order to alleviate the employer's compensation burden while ensuring swift and fair protection for afflicted workers. The substance of such insurance benefits under the LSAI Act should be understood as the government fulfilling the employer's LSA disaster compensation obligations in the form of insurance benefits."

- The Court further stated: "Thus, the various insurance benefits stipulated in LSAI Act Article 12-8, Paragraph 1, Items 1 to 5 can be said to be alternatives to their corresponding LSA disaster compensations."

II. The Purpose of Termination Compensation and Dismissal Restriction Exception

The Court then examined the rationale behind LSA Article 81 (termination compensation) and its link to the dismissal restriction in LSA Article 19:

- "The system of termination compensation stipulated in LSA Article 81 allows an employer, by providing a considerable amount of compensation, to terminate subsequent disaster compensation obligations. Concurrently, Article 19, Paragraph 1, proviso of said Act makes this an exception to the dismissal restriction in the main text of said paragraph, allowing the employer to be exempted from the burden arising from the prolonged medical treatment of the said worker."

III. Applying the Dismissal Restriction Exception When LSAI Benefits Are Paid

The core of the Supreme Court's reasoning lay in applying the principle of substantive equivalence:

- "Considering the substance of insurance benefits under the LSAI Act and their relationship with LSA disaster compensation... the disaster compensation that is an employer's obligation under the LSA can be said to be substantively fulfilled by the provision of alternative LSAI Act insurance benefits."

- Consequently, "there is no compelling reason to treat differently, with respect to the applicability of the proviso to Article 19, Paragraph 1, cases where disaster compensation is provided by the employer's own burden and cases where alternative LSAI Act insurance benefits are provided."

- The Court also addressed potential concerns about worker protection: "Furthermore, considering that even if termination compensation of a considerable amount is paid in the latter case [where LSAI benefits are received], necessary medical treatment compensation benefits under the LSAI Act will continue to be provided until the injury or illness is cured, it cannot be said that applying the proviso to Article 19, Paragraph 1 differently in these cases would result in a lack of protection for the worker's interests."

IV. Conclusion on LSA Article 81 and LSAI Medical Benefits

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court concluded:

- "A worker receiving medical treatment compensation benefits under LSAI Act Article 12-8, Paragraph 1, Item 1, should, concerning the application of LSA Article 19, Paragraph 1 (dismissal restriction), be considered as included among workers receiving compensation under the provisions of LSA Article 75, as referred to in LSA Article 81."

- Therefore, "When a worker receiving LSAI Act medical treatment compensation benefits continues to be uncured after three years from the start of medical treatment, the employer, by paying termination compensation under LSA Article 81, can avail themselves of the exception to the dismissal restriction provided in LSA Article 19, Paragraph 1, proviso, just as if the worker had been receiving direct employer-paid medical compensation under LSA Article 75."

Since University S had paid X termination compensation equivalent to 1200 days' average wage after X had been receiving LSAI medical benefits for over three years without being cured, the dismissal was not in violation of LSA Article 19, Paragraph 1. The High Court's finding to the contrary was deemed an error of law.

The case was remanded to the Tokyo High Court to determine whether the dismissal, while not violating LSA Article 19, might still be invalid under other principles, such as Article 16 of the Labor Contract Act (which prohibits dismissals lacking objectively reasonable grounds and social appropriateness, i.e., the abuse of dismissal right doctrine). (The commentary notes that the High Court on remand subsequently found the dismissal valid under this doctrine ).

Unpacking the Legal Framework and Its Implications

This Supreme Court decision resolved a significant point of contention in Japanese labor law concerning long-term work-related illnesses.

- The Core Debate: The main divergence between the lower courts and the Supreme Court was on the interpretation of LSA Article 81. The lower courts adopted a strict textual interpretation, focusing on Article 81's explicit reference to medical compensation provided by the employer under LSA Article 75. The Supreme Court, however, opted for a "substantive equivalence" approach, reasoning that since LSAI Act benefits replace and fulfill the employer's direct LSA compensation duties, the legal consequences attached to fulfilling those duties (like the ability to lift dismissal restrictions via termination compensation) should also apply when LSAI benefits are being provided.

- Rationale for "Substantive Equivalence": The commentary highlights several arguments that support the Supreme Court's stance, including the potential for inconsistent treatment of workers based on the severity of their condition (as the LSAI Act already provided a mechanism for lifting dismissal restrictions for very severe cases qualifying for an "injury/sickness compensation pension" after 1.5 years, if termination compensation was deemed paid). Denying the employer the ability to use termination compensation in less severe but still very prolonged LSAI medical benefit cases could create legal instability and place an indefinite burden on employers who are already contributing to the LSAI system.

- Critiques and Lingering Issues: The commentary also points to critiques of the Supreme Court's reasoning. Some scholars argue that the distinct purposes and operational mechanisms of the direct employer compensation under LSA and the social insurance system of the LSAI Act should not be so readily equated for all purposes. There are concerns that the decision did not sufficiently address the employee's potential for eventual rehabilitation and return to work, or fully consider the nature of the employer's "burden" when LSAI is covering most costs. The original legislative intent behind LSA Article 81 was primarily to relieve employers from the open-ended financial burden of direct and ongoing medical care and absence compensation. When the LSAI system shoulders this primary financial burden, the employer's remaining financial exposure is largely their LSAI premium contributions and potentially social insurance contributions for an employee still on the books but on long-term leave.

The commentary author suggests that while the Supreme Court aimed for a practical solution in this individual case, the underlying complexities and potential for perceived imbalances, especially for employees on long-term LSAI medical benefits who do not meet the disability thresholds for the LSAI injury/sickness compensation pension (where dismissal restriction lifting is more clearly outlined), might ideally warrant legislative clarification rather than relying solely on judicial interpretation.

The Overarching Principle of "Abuse of Dismissal Right"

It is crucial to remember, as the Supreme Court itself noted in its remand order, that even if the specific dismissal restriction under LSA Article 19 is lifted by the payment of termination compensation, the dismissal must still comply with the general principles governing dismissals in Japan. Specifically, under Article 16 of the Labor Contract Act, a dismissal will be void if it lacks objectively reasonable grounds and is not considered socially appropriate (this is the doctrine of abuse of the right to dismiss). Therefore, even after paying termination compensation, an employer must still have valid substantive reasons for the dismissal. Factors such as the employee's prognosis, the possibility of a return to work in any capacity, the employer's efforts (or lack thereof) to accommodate the employee, and the overall impact on the business would be relevant in this "abuse of right" assessment.

Conclusion: Clarifying a Path for Employers in Long-Term Sickness Cases

The Supreme Court's 2015 decision in the University S (Senshu University) case provided significant clarification for employers dealing with employees on very long-term medical leave for work-related conditions who are receiving benefits under the Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act. By endorsing a "substantive equivalence" approach, the Court confirmed that employers can, after three years of medical treatment and upon payment of the statutory termination compensation (1200 days' average wages), lift the LSA Article 19 dismissal restriction, even if the employee's medical care has been funded through the LSAI system rather than directly by the employer. This offers a mechanism for resolving protracted employment situations arising from long-term incapacity. However, any such dismissal remains subject to the overarching legal principle that it must not constitute an abuse of the employer's right to dismiss, requiring a careful consideration of all relevant circumstances.