Locked in or Free to Roam? Japanese Supreme Court on Exclusivity Clauses in M&A Basic Agreements

Judgment Date: August 30, 2004

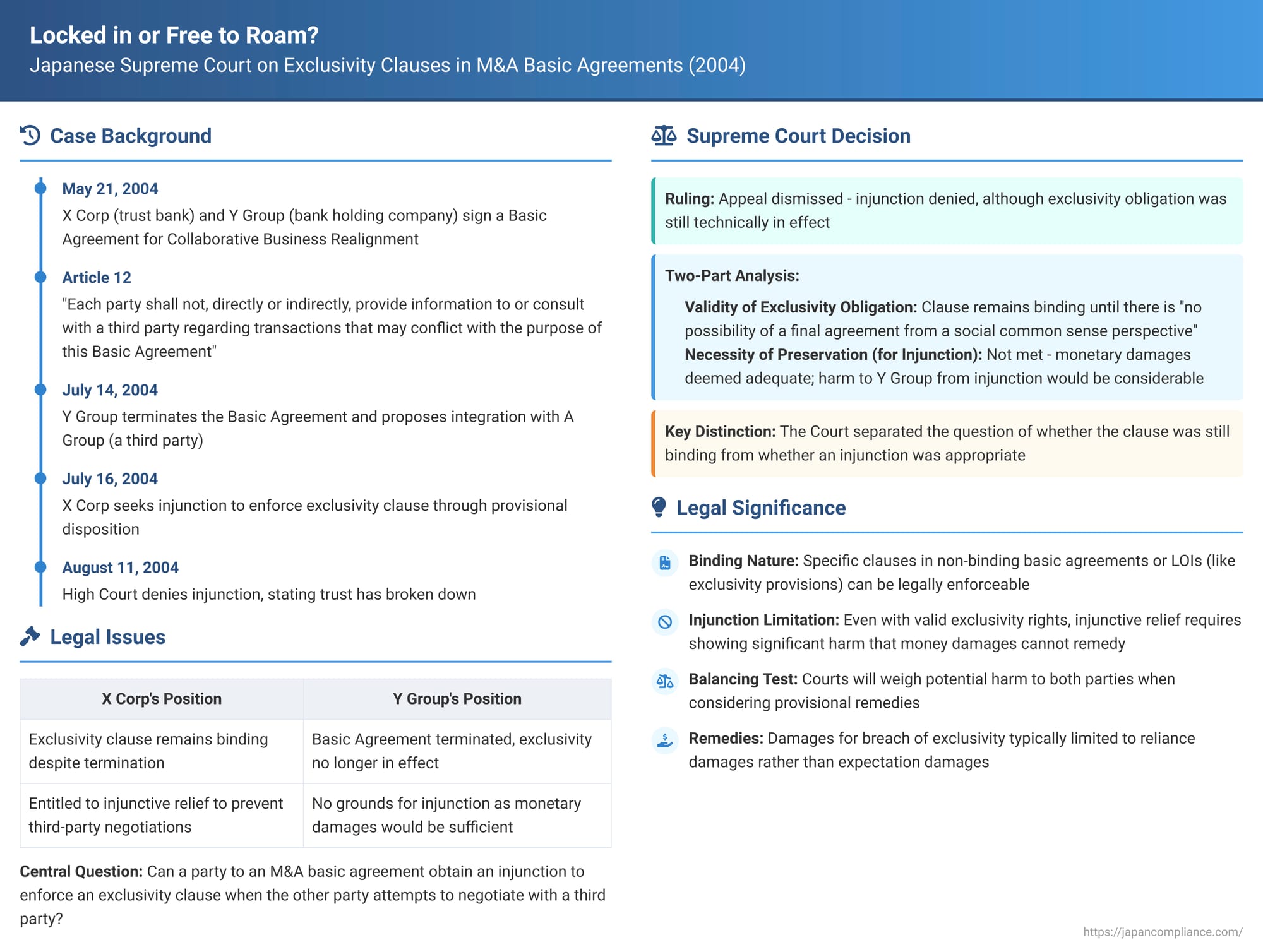

In the complex world of mergers and acquisitions (M&A), parties often enter into preliminary "basic agreements" – also known as Letters of Intent (LOIs) or Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) – to outline the general framework of a potential transaction before committing to a definitive, detailed contract. These basic agreements frequently contain "exclusivity clauses" (often termed "no-shop," "no-talk," or "exclusive negotiation" clauses) designed to prevent one party from negotiating with third parties for a specified period. A crucial 2004 Japanese Supreme Court decision shed light on the enforceability of such clauses, specifically addressing when the obligations under an exclusivity clause might cease and whether a party can obtain a court-ordered injunction (provisional disposition) to stop the other side from breaching it.

The High-Stakes Reorganization and the Basic Agreement

The case involved X Corp, a trust bank, and Y1 Corp, a bank holding company. Y1 Corp's group included Y2 Corp, another trust bank whose business operations were the target of a proposed major business reorganization. X Corp and Y1 Corp (representing the Y group entities, collectively "Y Group") entered into discussions for what they termed a "Collaborative Business Realignment." This realignment primarily involved the transfer of Y2 Corp's business (excluding certain corporate finance operations) to X Corp's group, alongside broader business collaboration between the X and Y groups.

On May 21, 2004, X Corp and Y Group formalized their preliminary understanding by signing a "Basic Agreement." This document, while outlining the intent to pursue the realignment, notably did not contain a legally binding obligation on either party to conclude a final, definitive agreement. It also lacked any specific provisions for penalties or liquidated damages if the exclusivity clause was breached.

However, Article 12 of the Basic Agreement, under the heading "Good Faith Negotiation," contained a crucial two-part provision. The first part stipulated a general duty for parties to negotiate in good faith regarding matters not covered in the Basic Agreement or if ambiguities arose. The second, and central, part of Article 12 (referred to in the judgment as "the Clause") stated:

"Furthermore, each party shall not, directly or indirectly, provide information to or consult with a third party regarding transactions, etc., that may conflict with the purpose of this Basic Agreement."

This was, in essence, an exclusivity or no-negotiation clause.

The Breakdown and the Switch

Following the execution of the Basic Agreement, X Corp and Y Group commenced negotiations to finalize the detailed terms of the Collaborative Business Realignment, with a target for concluding a definitive contract by the end of July 2004.

However, during this negotiation period, Y Group, reportedly facing its own pressing financial difficulties, came to the internal conclusion that its survival necessitated a different strategic path: a comprehensive business integration with an entirely different entity, A Group.

Consequently, on July 14, 2004, Y Group took decisive action:

- It formally notified X Corp that it was terminating the Basic Agreement.

- It simultaneously made a proposal to A Group for a full business integration, including the transfer of Y2 Corp's business operations (the very same operations that were the subject of the Basic Agreement with X Corp).

- Y Group publicly announced these developments.

The Legal Battle for Exclusivity: The Injunction Request

X Corp reacted swiftly. On July 16, 2004, asserting that Y Group's commencement of integration talks with A Group constituted a breach of X Corp's exclusive negotiation rights under the Clause in the Basic Agreement, X Corp applied to the Tokyo District Court for a provisional disposition (an interim injunction). X Corp sought to prohibit Y Group from providing information to, or consulting with, any third party (other than X Corp itself) concerning the transfer or succession of Y2 Corp's business operations, or any related mergers or company splits, for an extended period up to the end of March 2006.

- The Tokyo District Court initially granted X Corp's request, issuing the injunction. After Y Group filed an objection, the District Court reviewed the matter but ultimately upheld its initial decision, affirming the provisional disposition on August 4, 2004. Both rulings recognized the legal binding force of the Exclusivity Clause.

- Y Group then appealed to the Tokyo High Court. On August 11, 2004, the High Court reversed the District Court's decisions and dismissed X Corp's application for an injunction. The High Court's primary reasoning was that the trust relationship between X Corp and Y Group had, in its view, already been destroyed, and there was no longer any realistic expectation that sincere negotiations towards a final agreement for the Collaborative Business Realignment could continue. Therefore, the High Court concluded that the Exclusivity Clause had, for practical purposes, lost its effect for the future.

It's noteworthy that just a day after the High Court's ruling, on August 12, 2004, Y Group proceeded to sign a basic agreement with A Group for their proposed business integration. X Corp, disagreeing with the High Court's reasoning that the Clause had lost its effect, sought and obtained permission to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: A Two-Part Analysis

The Supreme Court, in its decision dated August 30, 2004, dismissed X Corp's appeal. While this upheld the High Court's outcome (the denial of the injunction), the Supreme Court's reasoning differed significantly, particularly concerning the continued validity of the Exclusivity Clause. The Supreme Court's judgment hinged on a two-part analysis:

Part 1: The Validity and Duration of the Exclusivity Clause Obligation

The Supreme Court first addressed whether the negative covenant (the obligation not to negotiate with third parties) imposed by the Exclusivity Clause had ceased to exist.

- Purpose of the Clause: The Court viewed the Clause as an agreement between X Corp and Y Group not to engage with third parties regarding transactions that could conflict with the Basic Agreement's purpose while they were actively negotiating towards a final agreement on the Collaborative Business Realignment. It was deemed "inextricably linked" to these negotiations and served as a "means" to conduct them smoothly, efficiently, and free from third-party interference, thereby facilitating the conclusion of a final agreement.

- When the Obligation Ceases: The Supreme Court stated that if, through the course of negotiations (or lack thereof), it becomes apparent from a "social common sense perspective" (社会通念上 - shakai tsūnen jō) that there is no longer any possibility of a final agreement being reached between the original parties, then the obligation under the Exclusivity Clause would also be extinguished.

- Application to the Facts (on this point): The Court acknowledged Y Group's termination notice, its public proposal to A Group, and the subsequent basic agreement with A Group. These events indicated that the likelihood of a final agreement between X Corp and Y Group was now "considerably low." However, the Court found that the situation had "not yet reached a point where all fluid elements had completely disappeared." It could not yet be definitively said, from a social common sense perspective, that there was absolutely no possibility of a final agreement between X Corp and Y Group.

- Conclusion on Clause Validity: Therefore, the Supreme Court held that the obligation arising from the Exclusivity Clause had not yet ceased to exist. This was a direct contradiction of the High Court's primary reason for denying the injunction.

Part 2: The "Necessity of Preservation" for a Provisional Disposition (Injunction)

Despite finding the Exclusivity Clause still technically in effect, the Supreme Court then turned to whether the requirements for granting a provisional disposition (injunction) under Article 23, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Provisional Remedies Act were met. This provision allows for such an injunction "when it is necessary to avoid significant harm or imminent danger to the creditor concerning the disputed legal right." This became the decisive ground for the Supreme Court's ruling.

- Nature of X Corp's "Right" and Harm from Breach: The Court noted that the Basic Agreement did not guarantee the conclusion of a final agreement for the Collaborative Business Realignment. X Corp only had an expectation that such an agreement might be reached. Therefore, the harm X Corp would suffer from Y Group breaching the Exclusivity Clause was not the loss of profits from a guaranteed finalized deal. Instead, the harm was characterized as the infringement of X Corp's expectation that it could negotiate with Y Group from an advantageous position, free from third-party interference, towards a potential final agreement.

- Assessing "Significant Harm or Imminent Danger": The Supreme Court weighed several factors:

- The nature of X Corp's harm (loss of an exclusive negotiation expectation) was deemed not to be so severe that it could not be adequately compensated by subsequent monetary damages.

- The probability of a final agreement actually materializing between X Corp and Y Group was, as already noted, "considerably low."

- The injunction sought by X Corp was for a lengthy period (until the end of March 2006).

- Conversely, the potential harm to Y Group if the injunction were granted would be "considerably large," given Y Group's stated dire financial situation and its perceived need to merge with A Group. Preventing these alternative negotiations could have severe consequences for Y Group.

- Conclusion on Necessity of Injunction: Balancing these considerations, the Supreme Court concluded that granting the provisional disposition to stop Y Group from negotiating with third parties was not necessary to prevent significant harm or imminent danger to X Corp. The requirements of Article 23, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Provisional Remedies Act were not met.

Thus, although the Exclusivity Clause was deemed to be still in force, the injunction was denied due to a lack of the requisite "necessity of preservation."

Unpacking the Legal Principles

This Supreme Court decision touches upon several important legal concepts relevant to M&A preliminary agreements:

- Binding Nature of Clauses in Basic Agreements: While basic agreements or LOIs often state that they are non-binding with respect to the ultimate transaction, specific clauses within them, such as those concerning exclusivity, confidentiality, or governing law, can be intended by the parties to be legally binding and enforceable. This case affirmed that an exclusivity clause could indeed have ongoing legal force.

- Termination of Exclusivity Obligations: The Supreme Court's "no possibility of a final agreement from a social common sense perspective" standard for when an exclusivity obligation ceases provides a more objective, albeit still somewhat flexible, test than the High Court's focus on the subjective breakdown of trust. The exact point at which this "no possibility" threshold is met remains open to interpretation in future cases (e.g., does it require the formalization of an alternative deal, shareholder approval of such a deal, or regulatory clearance?).

- Injunctive Relief is Extraordinary: The ruling underscores that an injunction (provisional disposition) is an extraordinary remedy. Even if a contractual right (like exclusivity) is being breached, an injunction will not automatically be granted. The applicant must demonstrate a genuine necessity for this pre-emptive relief, including that monetary damages would be an inadequate remedy and that the balance of hardships tips in their favor.

- Damages for Breach of Exclusivity: The Supreme Court acknowledged that X Corp might suffer damages due to Y Group's breach. The nature of these damages was defined as the loss of the expectation of negotiating exclusively and advantageously. In a subsequent lawsuit for damages brought by X Corp against Y Group (Tokyo District Court, February 13, 2006), X Corp's claim for expectation damages (profits it would have made had the collaborative deal gone through) was denied. This suggests that damages for breaching such a clause are more likely to be limited to reliance damages (e.g., costs incurred during the negotiation period). If the potential for such damages is low, it may reduce the practical "teeth" of exclusivity clauses unless accompanied by significant liquidated damages provisions (which themselves could raise other legal issues, such as directors' duties if the penalty is excessively high).

- Directors' Duties and "Fiduciary Out" Considerations: Although not directly addressed by the Supreme Court in its reasoning for denying the injunction, a background issue in enforcing strict exclusivity clauses is the potential conflict with the directors' fiduciary duties. If a board is locked into exclusive negotiations and a clearly superior offer from a third party emerges, adhering strictly to the exclusivity might breach the directors' duty to act in the best interests of the company and its shareholders. This sometimes leads to "fiduciary out" clauses being negotiated into agreements, or courts potentially implying such an out or even finding overly restrictive exclusivity clauses to be unenforceable if they unduly restrict directors' ability to consider better offers. The Supreme Court's focus on the "necessity of preservation" for the injunction might have been a way to resolve the immediate dispute without needing to delve into these complex fiduciary duty issues concerning the clause itself.

Conclusion

The August 30, 2004, Supreme Court decision provides a nuanced perspective on the enforcement of exclusivity clauses in M&A basic agreements. It establishes that while such a clause can remain legally binding even if one party attempts to terminate the underlying agreement and pursue other options, obtaining an injunction to enforce that exclusivity is a separate and more demanding hurdle. The Court will rigorously assess whether such injunctive relief is truly necessary to prevent significant and irreparable harm, carefully balancing the interests and potential hardships of all parties involved. In this instance, even with a technically surviving exclusivity obligation, the perceived adequacy of monetary damages for the specific harm suffered, combined with the low probability of the original deal succeeding and the significant potential harm to the breaching party if enjoined, led the Court to deny injunctive relief. This ruling highlights the practical challenges of rigidly enforcing exclusive negotiation periods in the dynamic and often rapidly evolving landscape of corporate M&A.