Local Taxing Power vs. National Law: Japan's Supreme Court on Kanagawa's Special Corporate Tax

Judgment Date: March 21, 2013

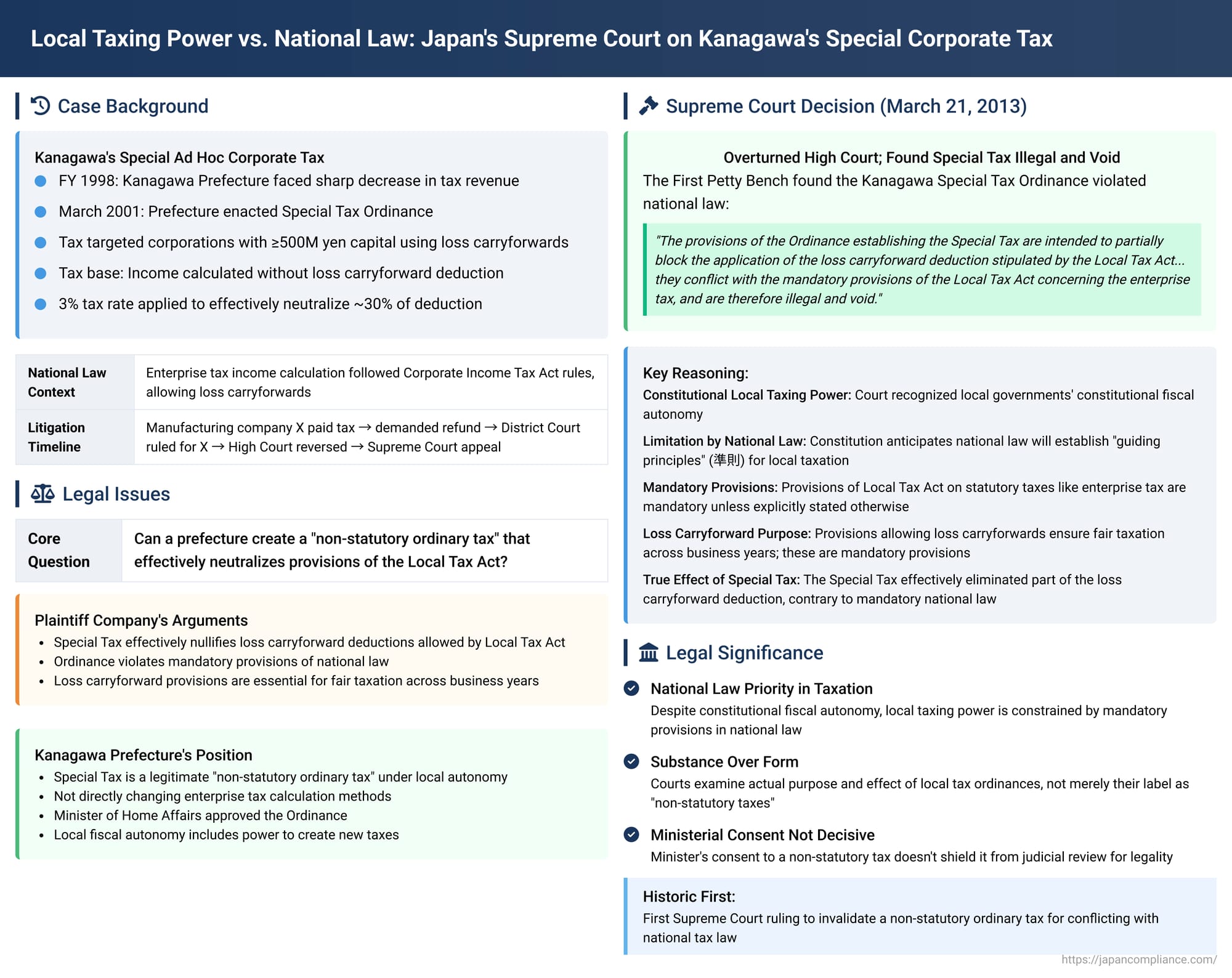

In a landmark decision clarifying the boundaries of local government taxing authority in Japan, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court struck down a special corporate tax implemented by Kanagawa Prefecture. The Court found that the "Kanagawa Prefectural Special Ad Hoc Corporate Tax," a type of "non-statutory ordinary tax" created by a prefectural ordinance, illegally conflicted with mandatory provisions of the national Local Tax Act concerning the standard enterprise tax, particularly its rules on loss carryforwards. This case marked the first time the Supreme Court invalidated a non-statutory ordinary tax for such a conflict.

Background: Kanagawa's Fiscal Challenge and the "Special Tax"

The case arose from fiscal pressures faced by Kanagawa Prefecture. In Fiscal Year (FY) 1998, the prefecture experienced a sharp decrease in tax revenue. In response, a prefectural research group was established. In May 2000, this group issued an interim report suggesting that if a nationwide system of enterprise tax based on external standards (such as company size rather than just profit, known as 外形標準課税 - gaikei hyojun kazei) was not introduced soon, Kanagawa Prefecture should consider creating its own "non-statutory ordinary tax" (法定外普通税 - hoteigai futsuzei) to effectively prevent corporations from utilizing certain loss carryforward deductions against their enterprise tax liabilities.

The national tax reforms for FY2001 did not introduce the anticipated nationwide external standard taxation for enterprise tax. Following a final report from its research group in January 2001, Kanagawa Prefecture proceeded to enact the "Kanagawa Prefectural Special Ad Hoc Corporate Tax Ordinance" (hereinafter "the Ordinance") in March 2001. This Ordinance, which established the "Special Ad Hoc Corporate Tax" (referred to as "the Special Tax"), received the formal consent of the (then) Minister of Home Affairs and came into effect.

Key Features of the Kanagawa Special Tax

The Special Tax, as defined by the Ordinance, had the following main characteristics:

- Taxpayers: It was levied on corporations with a stated capital of 500 million yen or more that had offices or places of business within Kanagawa Prefecture.

- Taxable Years: The Special Tax applied to business years in which a corporation utilized loss carryforward deductions when calculating its income for the standard prefectural enterprise tax.

- Tax Base: The tax base for the Special Tax was defined as the amount equivalent to the corporation's income for that business year if calculated without applying the loss carryforward deduction. However, this amount was capped at the actual amount of the loss carryforward deduction claimed for enterprise tax purposes.

- Tax Rate: The rate for the Special Tax was set at 3%.

Underpinning this local initiative were existing national tax laws:

- The Local Tax Act (before its 2003 amendment) stipulated that the tax base for the standard corporate enterprise tax was, in principle, the income of each business year. This income was to be calculated largely following the same rules used for determining income for national corporate income tax purposes.

- The National Corporate Income Tax Act allowed corporations filing "blue form" tax returns to carry forward net operating losses (欠損金 - kessonkin) incurred in business years that began within the previous seven years (five years before a 2004 national amendment) and deduct these losses from their income in subsequent years. This loss carryforward provision was thus also applicable to the calculation of income for the local enterprise tax.

Following the enactment of the Special Tax Ordinance, the national Local Tax Act was amended in 2003 to partially introduce external standard taxation for the enterprise tax. Kanagawa Prefecture subsequently amended its Special Tax Ordinance in 2004. The Special Tax Ordinance itself was set to generally expire on March 31, 2009.

The Plaintiff's Challenge

The plaintiff, X (appellant in the Supreme Court), was a manufacturing company with a factory in Kanagawa Prefecture and capital exceeding 500 million yen. In its FY2003 and FY2004 business years, X had incurred losses that were carried forward and utilized as deductions in calculating its enterprise tax. X declared and paid the Special Tax for these years in accordance with the Ordinance. However, X later filed a claim against Kanagawa Prefecture for a refund of the amounts paid, arguing that the Ordinance was illegal and void because it violated the provisions of the national Local Tax Act.

The Yokohama District Court (court of first instance) ruled in favor of X. It found that the Special Tax effectively nullified the loss carryforward deductions allowed for enterprise tax and declared the Ordinance illegal and void. However, the Tokyo High Court (appellate court) reversed this decision, ruling in favor of Kanagawa Prefecture. It held that the Ordinance did not substantially change the provisions of the Local Tax Act concerning enterprise tax and therefore did not violate it. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling

The Supreme Court overturned the Tokyo High Court's decision and reinstated the District Court's ruling, thereby finding Kanagawa's Special Tax Ordinance illegal and void. The Court's comprehensive reasoning addressed the constitutional status of local taxing power and the criteria for determining conflicts between local ordinances and national laws.

I. The Test for Conflict Between Ordinances and National Laws

The Court began by referencing its established test from the 1975 Tokushima City Public Safety Ordinance case: "Whether an ordinance violates a national law or regulation is to be determined not merely by making a superficial comparison of the wording of their respective provisions, but by comparing their respective purposes, objectives, content, and effects to ascertain whether any contradiction or conflict exists between them."

II. Constitutional Basis of Local Taxing Power

The Supreme Court, for the first time, explicitly affirmed the principle of "fiscal autonomy" (jishu zaisei shugi) for local governments. It stated:

"Ordinary local public entities, in accordance with the principle of local autonomy, possess the authority to manage their property, administer their affairs, and execute their administration (Constitution, Articles 92 and 94). To carry out these functions in accordance with this principle, it is necessary for them to have the authority to procure their own financial resources. From this, it is understood that ordinary local public entities are constitutionally envisioned as subjects of taxing power, separate from the national government, as an indispensable element of local autonomy."

III. Limitations on Local Taxing Power by National Law

Despite this inherent taxing power, the Court outlined its constitutional and statutory limitations:

The Constitution does not specify the concrete content of local taxing power. Instead, it stipulates that matters concerning the organization and operation of local public entities shall be fixed by law (Article 92), and that local public entities can enact ordinances within the scope of law (Article 94). Furthermore, the Court noted that the imposition of taxes requires coordination from the perspective of the overall tax burden on citizens and the allocation of financial resources between national and local governments, as well as among local governments themselves.

In light of these considerations, the Court reasoned that, under the principle of "taxation by law" (Constitution, Article 84), the Constitution anticipates that national law will establish "guiding principles" (junsoku) for local taxation, covering aspects such as tax items, taxable objects, tax bases, and tax rates, while respecting the principle of local autonomy. When such guiding principles are laid down by national law, the taxing power of local public entities must be exercised in accordance therewith and within the scope thereof.

IV. The Local Tax Act's Provisions as Mandatory Law

The Court then focused on the nature of the Local Tax Act:

The Local Tax Act defines "statutory ordinary taxes" (hotei futsuzei), such as the enterprise tax, which local public entities are generally obligated to levy, except in special circumstances (e.g., if collection costs are disproportionately high). The Act provides detailed and specific regulations for these statutory taxes, covering tax items, taxable objects, tax bases, calculation methods, standard and limit tax rates, non-taxable items, and special exemptions.

From this, the Court concluded that the provisions of the Local Tax Act concerning statutory ordinary taxes are, unless explicitly stated otherwise (as in the case of standard tax rates, which allow for local variation within limits), to be construed as mandatory provisions (kyoko kitei), not merely optional guidelines. Local public entities are therefore bound by these guiding principles in the Local Tax Act when enacting or amending their tax ordinances.

Consequently, it is impermissible for an ordinance dealing with a statutory ordinary tax to alter the content of such mandatory provisions of the Local Tax Act. Crucially, the Court extended this logic: it is equally impermissible for an ordinance establishing a non-statutory ordinary tax (like Kanagawa's Special Tax) to include provisions that contradict and thereby substantially alter the content of the mandatory provisions governing statutory ordinary taxes. Such an ordinance would be deemed contrary to the purpose and objectives of the Local Tax Act and would obstruct its intended effects.

V. Loss Carryforward Deduction as a Mandatory Provision

The Court then specifically addressed the loss carryforward deduction:

The loss carryforward deduction under the national Corporate Income Tax Act (which the Local Tax Act incorporates by reference for calculating enterprise tax income) serves the purpose of mitigating the potential for excessive tax burdens that can arise because income is calculated for artificial annual periods. It aims to average out income and losses across multiple business years, ensuring that tax burdens are as equitable as possible regardless of year-to-year fluctuations in profitability. This, the Court stated, is a provision that must necessarily be applied.

Therefore, the provisions of the Local Tax Act that mandate the application of this loss carryforward deduction (by referencing the national Corporate Income Tax Act's rules) for calculating the income base of the enterprise tax are mandatory provisions of the Local Tax Act.

Given this, the Court asserted that it is impermissible for a local ordinance to exclude the application of this statutory loss carryforward deduction, even partially. If an ordinance were to contain such exclusionary provisions, those provisions would directly conflict with the mandatory rules of the Local Tax Act and would therefore be illegal and void.

VI. The True Nature and Effect of Kanagawa's Special Tax

The Court then analyzed the substance and effect of the Kanagawa Special Tax Ordinance:

At first glance, Article 7, Paragraph 1 of the Ordinance, defining the tax base for the Special Tax, appeared to be based on the income of the business year calculated, in principle, without deducting carried-forward losses. However, the same paragraph included a crucial parenthetical clause: the tax base was capped at an amount equivalent to the carried-forward loss that was actually deducted for enterprise tax purposes. Considering that the maximum amount of loss that can be carried forward is, by definition, the income before such deduction (Corporate Income Tax Act, Article 57, Paragraph 1, proviso), the Court concluded that the substance of the Special Tax base was nothing other than the amount of the carried-forward loss itself.

This structure, the Court found, effectively resulted in a partial elimination of the loss carryforward deduction that would otherwise apply to the calculation of the standard enterprise tax.

The Court also considered the documented legislative history of the Special Tax, including the final report of the prefectural research group. This history indicated that the Ordinance was enacted with the explicit intention of blocking the application of approximately 30% of the loss carryforward deductions for enterprise tax purposes.

VII. Conclusion: Illegality of the Special Tax Ordinance

Based on this analysis, the Supreme Court concluded:

"The provisions of the Ordinance establishing the Special Tax are intended, as their purpose and objective, to partially block the application of the loss carryforward deduction stipulated by the Local Tax Act. Through the imposition of the Special Tax, they produce the effect of substantially and partially eliminating the loss carryforward deduction in the calculation of income for each business year. In relation to the provisions of the Local Tax Act which mandate the necessary application of the loss carryforward deduction for the purpose of leveling income and losses across business years and achieving fair taxation by equalizing corporate tax burdens as much as possible regardless of income fluctuations, these Ordinance provisions are contrary to the purpose and objective of the Local Tax Act and obstruct its effects. As such, they conflict with the mandatory provisions of the Local Tax Act concerning the enterprise tax, and are therefore illegal and void."

Judgment and Its Significance

The Supreme Court thereby reversed the Tokyo High Court's decision and affirmed the Yokohama District Court's original judgment in favor of the plaintiff company, X. Kanagawa Prefecture was consequently obliged to refund the Special Tax paid by corporations.

This case is a landmark for several reasons:

- Reinforcing National Law Supremacy in Taxation: It clearly establishes that while local governments possess constitutionally recognized fiscal autonomy, their power to create local taxes, even "non-statutory" ones, is constrained by national law, particularly the mandatory provisions of the Local Tax Act concerning established statutory taxes.

- Substance Over Form: The ruling emphasizes that courts will look beyond the mere form or name of a local tax to its actual substance and effect when determining if it conflicts with national legislation. Kanagawa's attempt to characterize the Special Tax as a distinct "non-statutory ordinary tax" did not prevent the Court from finding that its true purpose and effect was to alter the application of the statutory enterprise tax.

- "Guiding Principles" (Junsoku) and Mandatory Provisions: The decision provides significant interpretation of the Local Tax Act's role in providing "guiding principles" for local taxation, deeming many of its core provisions for statutory taxes as "mandatory." This limits the scope for local deviation.

- Impact on Local Fiscal Autonomy: While affirming fiscal autonomy in principle, the judgment sets clear limits, indicating that local initiatives to raise revenue cannot contravene the nationally established framework for core taxes like the enterprise tax. It suggests that significant alterations to such frameworks desired by local governments may need to be pursued through amendments to national law rather than purely local ordinances.

- Irrelevance of Ministerial Consent for Legality: The fact that the Minister of Home Affairs had consented to the Ordinance did not sway the Court's judgment on its legality. The supplementary opinion by Justice Kinzuchi emphasized that ministerial consent for non-statutory taxes is primarily a policy-level control and does not confer legality if the ordinance otherwise conflicts with higher law, nor does it bind judicial review.

The Kanagawa Special Ad Hoc Corporate Tax case serves as a critical precedent in defining the delicate balance between local fiscal initiative and the coherence of the national tax system. It underscores that local autonomy, while constitutionally protected, operates within the framework established by national law, especially concerning fundamental aspects of established tax categories.