Local Power, National Rules: Japan's Supreme Court on Ordinances and Penal Sanctions

A Foundational Grand Bench Ruling from May 30, 1962

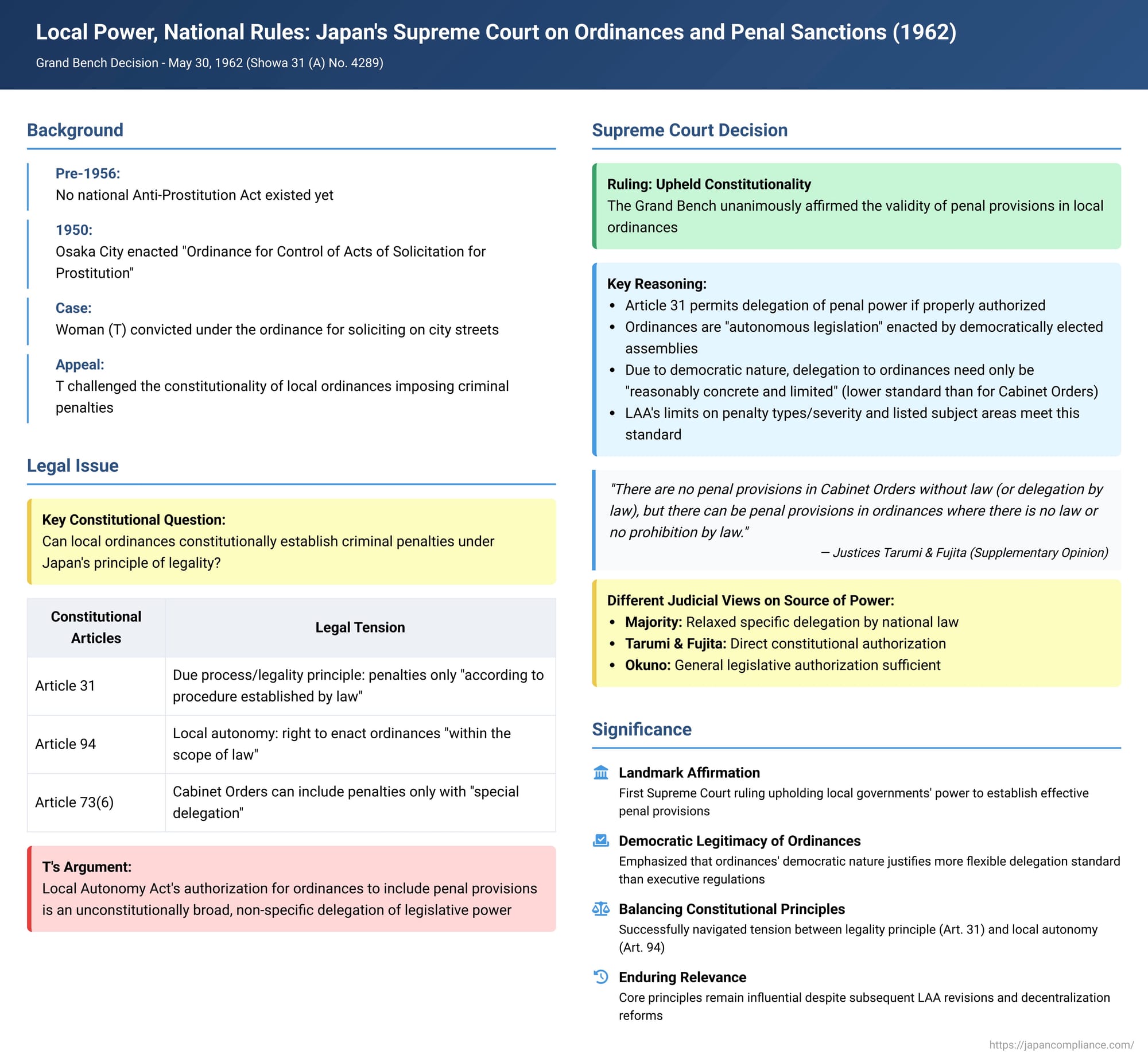

In any nation with a system of local governance, a fundamental constitutional question arises: to what extent can local authorities create and enforce their own rules, particularly when those rules carry penal sanctions? This issue brings into focus the delicate balance between local autonomy – the ability of communities to address their specific needs – and the overarching principle of legality, which often dictates that the power to define crimes and prescribe punishments should reside with the national legislature. A landmark decision by the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on May 30, 1962 (Showa 31 (A) No. 4289), delved deep into this matter, examining the constitutionality of local ordinances imposing criminal penalties.

The Case of T in Osaka: A City Ordinance Before National Law

The defendant in this case, a woman referred to as T, was charged and convicted in the lower courts for violating a local ordinance in Osaka City. Specifically, she was found to have solicited passersby for the purpose of prostitution on the city streets. This act was prohibited by Article 2, paragraph 1, of Osaka City's "Ordinance for the Control of Acts of Solicitation for Prostitution, etc., in Streets and Other Public Places" (Osaka City Ordinance No. 68 of 1950).

It's important to note the legal landscape at the time of T's offense: the national Anti-Prostitution Act (Law No. 118 of 1956) had not yet been enacted. This meant that Osaka City was addressing a matter of public morality and order through its own local legislation in the absence of a comprehensive national framework specifically targeting such acts.

The Constitutional Challenge: Delegation of Penal Power

T's appeal to the Supreme Court did not primarily contest the facts of her actions. Instead, her defense mounted a fundamental constitutional challenge against the very basis of the ordinance's penal provisions. The argument centered on the Local Autonomy Act (LAA), the national law that empowers local public entities to enact ordinances. At the time, Article 14, paragraph 1, and paragraph 5 of the LAA (old version, corresponding to the current Article 14, paragraph 3) authorized local governments to include penal provisions in their ordinances – such as imprisonment (up to two years), fines (up to 100,000 yen), penal detention, minor fines, or confiscation – for violations of those ordinances, unless otherwise stipulated by a specific national law.

The defense contended that this provision in the LAA constituted an unconstitutionally broad and non-specific delegation of legislative power to local authorities. Article 31 of the Constitution of Japan states: "No person shall be deprived of life or liberty, nor shall any other criminal penalty be imposed, except according to procedure established by law." This is Japan's due process clause, which is understood to embody the principle of legality (nullum crimen sine lege, nulla poena sine lege), meaning that crimes and punishments must be clearly defined by "law"—which, in its strictest sense, refers to statutes enacted by the National Diet, Japan's parliament. T's argument was that the LAA effectively gave local governments a "blank cheque" to create new crimes and punishments, thereby undermining this fundamental constitutional safeguard.

The Supreme Court's Decision of May 30, 1962

The Grand Bench of the Supreme Court dismissed T's appeal, upholding her conviction and, more significantly, affirming the constitutionality of the LAA's provisions authorizing ordinances to carry penal sanctions.

Core Reasoning on Delegated Legislative Power:

The Court's majority opinion meticulously addressed the constitutional concerns:

- Delegation is Permissible: The Court first established that Article 31 of the Constitution does not strictly require all criminal penalties to be directly stipulated within statutes enacted by the Diet itself. It acknowledged that penal provisions can be established by subordinate legislation (such as ordinances enacted by local governments or cabinet orders issued by the executive) provided there is a proper authorization from a Diet-enacted law. This interpretation, the Court noted, is supported by Article 73, item 6, proviso, of the Constitution, which explicitly allows Cabinet Orders (政令 - seirei) to include penal provisions "in cases of special delegation by that law."

- No "Blank Cheque" Delegation: While permitting delegation, the Court emphasized that such statutory authorization cannot be an "unspecified, general, blank-cheque type of delegation." The empowering law must provide sufficient guidance and limits.

- The Special Nature of Ordinances: Crucially, the Court distinguished ordinances from other forms of subordinate legislation, like executive orders. Ordinances, it highlighted, are "autonomous legislation" (自治立法 - jichi rippō) enacted by local assemblies, the members of which are directly elected by the local populace. In this respect, ordinances share a democratic legitimacy akin to laws passed by the National Diet, which is also composed of publicly elected representatives. This democratic pedigree sets them apart from regulations created solely by administrative bodies.

- "Reasonably Concrete and Limited" Delegation for Ordinances: Given their democratic nature, the Court reasoned that when a law authorizes ordinances to establish penal provisions, the standard for the specificity of that delegation can be less stringent than for delegation to purely executive orders. The authorization needs only to be "to a reasonable degree concrete and limited."

- LAA Provisions Meet the Standard: The Court found that the LAA, as it existed at the time, met this standard.

- Article 2, paragraph 3 of the LAA then listed various affairs that local public entities could handle, including (item 1) "maintaining the safety, health, and welfare of residents and sojourners" and (item 7) "restricting acts that defile morals or cleanliness, and other matters concerning public health and purification of morals." The Court described these listed subject matters as being "considerably concrete in content."

- Furthermore, Article 14, paragraph 5 of the LAA explicitly limited the types and maximum severity of penalties that ordinances could impose (e.g., imprisonment up to two years, fines up to 100,000 yen).

- Therefore, the LAA's framework—authorizing ordinances to set penalties within these defined subject areas and within these prescribed penal limits—was deemed a sufficiently concrete and limited delegation of power. It was not an unconstitutional "blank cheque."

The Court concluded that imposing penalties through ordinances enacted under such a statutory framework aligns with the constitutional requirement of Article 31 that penalties be imposed "according to procedure established by law." Consequently, the LAA provisions were constitutional, and so was the Osaka City Ordinance based upon them.

The Court also dismissed the defendant's other arguments, stating that in the absence of a specific national law at the time (pre-Anti-Prostitution Act), Osaka City was well within its rights under Article 94 of the Constitution and the LAA to regulate street solicitation via an ordinance with penal provisions. The claim that punishing such acts contravened the prevailing legal order was also rejected.

Key Principles from the Majority Opinion

The majority opinion in this 1962 case established several enduring principles:

- Democratic Legitimacy of Ordinances: It underscored the unique character of ordinances as a form of democratic legislation stemming from elected local assemblies, distinguishing them from executive-branch regulations.

- Flexible Standard for Delegation: It introduced a more flexible standard for the delegation of penal power to ordinances, requiring the authorization to be "reasonably concrete and limited" rather than demanding the high level of specificity that might be expected for delegation to purely administrative decrees.

The Spectrum of Judicial Views: The Supplementary Opinions

The decision was unanimous in its outcome (dismissing the appeal), but several Justices offered supplementary opinions, revealing a fascinating spectrum of reasoning on the precise constitutional basis for ordinances to carry penal sanctions. These opinions highlight the depth of the legal debate:

- Justice Irie's View (Relaxed Specific Delegation): Justice Irie agreed that ordinances require legal delegation for penal provisions, akin to Cabinet Orders under Article 73(6), proviso, which demands specific delegation. However, he argued that because ordinances are products of democratic local assemblies, the degree of specificity required for this delegation can be "more lenient" than that for executive orders. He found that LAA Article 14(5), when read in conjunction with the then-existing Article 2 (listing local government functions), provided a sufficiently specific (albeit relaxed) delegation.

- Justice Tarumi's View (joined by Justice Fujita - Direct Constitutional Authorization): This opinion offered a fundamentally different rationale. Justices Tarumi and Fujita contended that ordinances, unlike Cabinet Orders, do not require a specific delegation from a particular law to enact penal provisions. They argued that the power to enact ordinances, granted by Article 94 of the Constitution ("Local public entities... may enact ordinances within the scope of law"), inherently includes the power to make them effective, which means including penal provisions. For them, LAA Article 14(5) was not a delegating statute but rather a law that defined and limited the scope (e.g., maximum penalties) within which this constitutionally derived power could be exercised. In their memorable phrasing: "There are no penal provisions in Cabinet Orders without law (or delegation by law), but there can be penal provisions in ordinances where there is no law or no prohibition by law."

- Justice Okuno's View (General Delegation Sufficient for Ordinances): Justice Okuno also concurred, believing that delegating penal power to subordinate legislation is constitutionally permissible if the empowering law establishes certain limits and standards. He agreed that ordinances, due to their creation by representative local assemblies, do not require the same kind of specific, individual delegation as Cabinet Orders under Article 73(6), proviso. He viewed LAA Article 14(5) as a general authorization for ordinances to set penalties, which is acceptable given their democratic nature and the limitations on subject matter and penalty severity imposed by the LAA. However, he disagreed with the majority's implication that the (then-existing) list of local affairs in LAA Article 2(3) made the delegation in Article 14(5) "specific"; rather, he saw Article 14(5) itself as a general enabling provision for all permissible ordinance matters. He also explicitly disagreed with Justice Tarumi's view that Article 94 of the Constitution alone, without LAA Article 14(5), would grant local governments the power to enact penal statutes.

Understanding the Broader Legal Framework

This case touches upon several key articles of the Japanese Constitution and the Local Autonomy Act:

- Constitution Article 31 (Due Process and Principle of Legality): The core safeguard against arbitrary punishment, requiring crimes and penalties to be established by law.

- Constitution Article 94 (Local Autonomy): Grants local public entities the right to manage their property, affairs, and administration, and to "enact their own ordinances within the scope of law."

- Constitution Article 73(6), proviso (Penalties in Cabinet Orders): Allows Cabinet Orders to include penal provisions only "in cases of special delegation by that law," setting a high bar for executive branch penal rulemaking.

- Local Autonomy Act Article 14(5) (Old Version, now Art. 14(3)): The statutory provision directly authorizing local ordinances to establish penal provisions within certain limits.

Significance and Evolution of Thought

The 1962 Supreme Court decision was a landmark for several reasons:

- Affirmation of Local Penal Power: It was the first definitive Supreme Court ruling to uphold the constitutionality of the LAA's general authorization for local ordinances to include penal provisions, a crucial element for effective local governance.

- The "Democratic Nature of Ordinances": A key takeaway from the majority opinion, and echoed in some supplementary opinions, is the emphasis on the democratic process behind ordinances. Because they are enacted by locally elected assemblies, they are treated with a degree of deference regarding penal rulemaking power that is not accorded to purely executive regulations.

- Enduring Debate on the Source of Power: The case vividly illustrates the ongoing jurisprudential debate in Japan about the precise constitutional wellspring of the power of ordinances to set penalties:

- Is it derived from a (necessarily somewhat relaxed) delegation by national law (the Diet), as the majority and Justice Irie suggested?

- Or does it flow more directly from the constitutional grant of ordinance-making power itself (Article 94), with national law merely setting the outer boundaries, as Justices Tarumi and Fujita argued?

- Or is a general authorization by national law, tailored for the democratic nature of ordinances, the appropriate model, as Justice Okuno proposed?

- Relevance in Light of LAA Revisions: Legal commentators have noted that the majority opinion's reliance on the "considerably concrete" list of local government affairs in the old LAA Article 2(3) as a basis for finding the delegation sufficiently specific might face challenges today. The LAA has since been revised, and such illustrative lists of affairs have been removed, aiming to give local governments broader discretion. This could lend more weight to theories (like Justice Tarumi's) that ground penal power more directly in the constitutional status of ordinances or in a general authorization, rather than in specific (and now absent) subject-matter lists within the LAA.

- Impact of Decentralization: Subsequent waves of decentralization reform in Japan have aimed to further empower local governments and emphasize their role as autonomous legislative bodies. This trend might also bolster arguments for a more inherent or broadly authorized power for ordinances to include necessary enforcement mechanisms, including penalties.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1962 ruling in the Osaka City Ordinance case remains a foundational decision in Japanese constitutional and administrative law. It affirmed the vital power of local governments to enforce their policies through penal sanctions, thereby ensuring that ordinances are not mere "paper tigers." While upholding this power, the Court also navigated the essential requirements of the principle of legality under Article 31 of the Constitution, emphasizing that such local penal authority must ultimately be grounded in, and limited by, national law. The rich array of opinions within the Grand Bench decision continues to fuel discussion about the precise nature and scope of local legislative power, a debate that remains highly relevant as Japan continues to evolve its system of local autonomy.