Loan Under Duress, Funds Paid to a Stranger: Who Owes What? A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Unjust Enrichment

Date of Judgment: May 26, 1998

Case Name: Claim for Promissory Note Payment

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Introduction

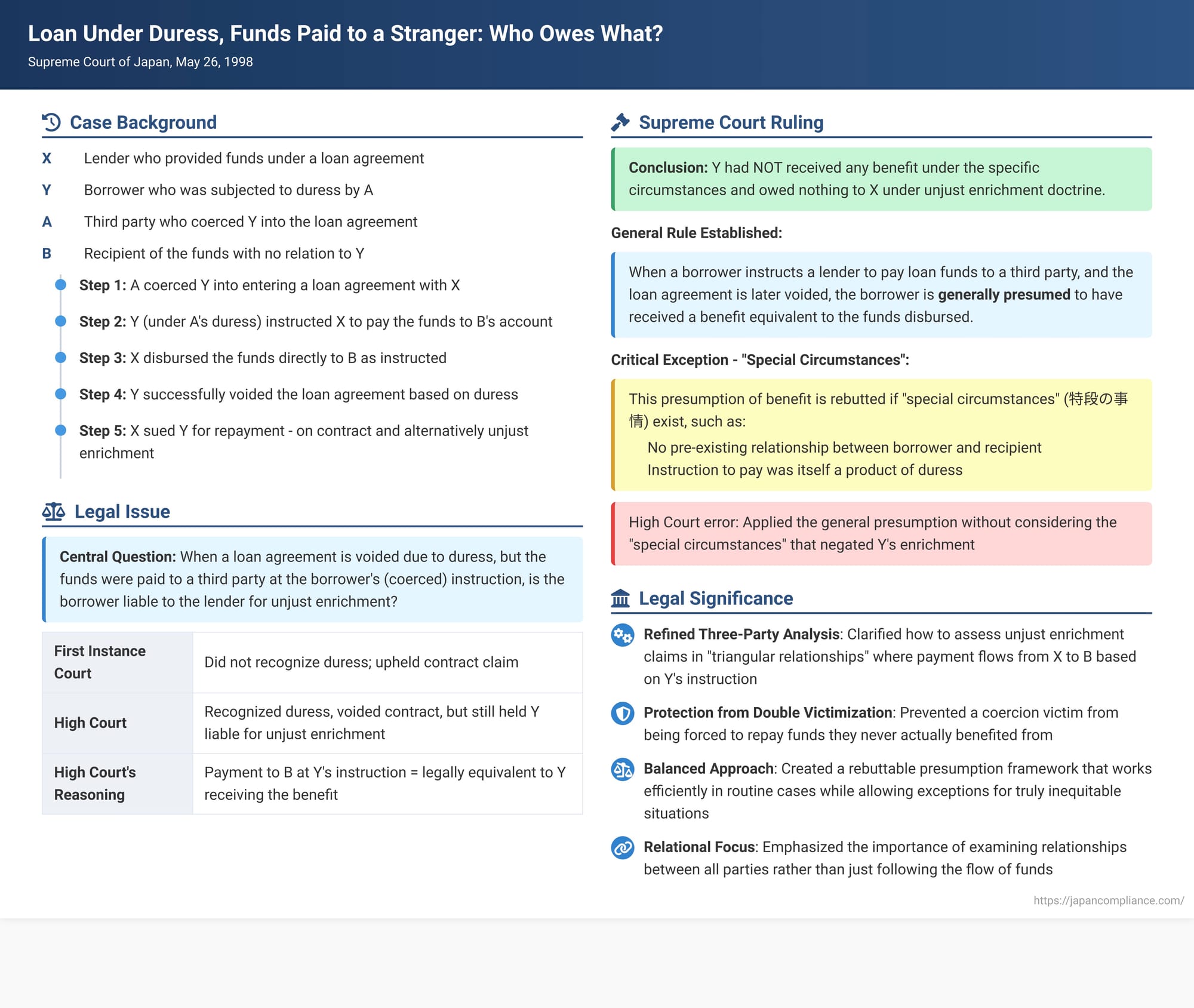

Unjust enrichment law aims to correct situations where one person benefits at another's expense without a valid legal reason. These situations can become particularly complex when they involve three or more parties. Consider this scenario: a lender provides funds, but due to a voided loan agreement, seeks their return. What if the borrower, under duress, had instructed the lender to pay those funds directly to an unrelated third party? Is the coerced borrower still considered to have "benefited" and therefore liable to repay the lender? A Japanese Supreme Court decision from May 26, 1998, delved into this intricate web of relationships.

A Loan Born of Coercion: The Factual Background

The case presented the following circumstances:

- The Coerced Loan: Y was subjected to duress (coercion) by an individual, A. Under this duress, Y was forced to enter into an interest-bearing loan agreement (the "Subject Loan Agreement") with X, who acted as the lender.

- Instructed Payment to a Third Party: As part of this coerced transaction, Y, still acting under A's duress, instructed X (the lender) to disburse the loan funds directly into the bank account of a third party, B. Crucially, Y had no prior legal or factual relationship with B; B was essentially a stranger to Y, and the instruction to pay B was solely due to A's dictates.

- Loan Agreement Voided: Y subsequently took legal steps and successfully had the Subject Loan Agreement with X voided (cancelled) on the grounds of the duress exerted by A.

- Lender Seeks Repayment: X (the lender), having disbursed the funds to B at Y's (coerced) instruction but now facing a voided loan agreement with Y, sued Y for the return of the loan amount. X's primary claim was for repayment under the loan agreement itself, and alternatively, for the return of the funds based on the principle of unjust enrichment (arguing Y had benefited from the loan disbursement).

- Lower Court Rulings:

- The first instance court did not initially recognize the duress against Y and upheld X's claim for loan repayment under the contract.

- The High Court, however, did acknowledge that Y had acted under duress and that the loan agreement with X was therefore validly voided. Despite this, the High Court still found Y liable to X under the alternative claim of unjust enrichment. It reasoned that X's disbursement of funds to B at Y's instruction was legally equivalent to X having first paid the funds to Y, and Y then choosing to pass them on to B. Therefore, the High Court concluded that Y had, in legal contemplation, received a "benefit" from X's disbursement.

Y, the coerced borrower, appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court, arguing that Y had received no actual benefit from the transaction.

The Supreme Court's Analysis

The Supreme Court, on May 26, 1998, overturned the High Court's ruling on the unjust enrichment claim. It found that Y had not received any benefit from X's payment to B under these specific circumstances and, therefore, Y owed nothing to X under the doctrine of unjust enrichment.

The General Rule in Instructed Third-Party Payments (When the Primary Contract is Voided)

The Supreme Court first laid out a general principle for such three-party situations:

- If a borrower (like Y) under a loan agreement instructs the lender (X) to disburse the loan funds to a third party (B), and the lender complies, but the loan agreement between the lender and borrower is later voided (e.g., for duress, mistake, etc.), the borrower (Y) is generally presumed to have received a benefit equivalent to the value of the funds disbursed by the lender (X) to the third party (B).

- Rationale for this general presumption:

- Usual Benefit to the Instructing Party: In typical scenarios, even if funds go directly to a third party, the instructing party (the borrower Y) usually derives some benefit in their own relationship with that third party. For instance, the payment might satisfy a debt Y owes to B, or fulfill some other obligation Y has towards B. It's common for some pre-existing legal or factual connection to exist between the party giving the instruction and the ultimate recipient.

- Burden of Proof on Lender: The lender (X), who acts in good faith based on the borrower's (Y's) instruction, is not always aware of the specific details of the relationship between the borrower (Y) and the third-party recipient (B). To require the lender to prove the exact nature and extent of the borrower's benefit in such indirect payment situations would place an unreasonable burden on the lender.

- Equitable Treatment: Treating a direct X-to-B payment (made at Y's instruction) differently from a two-step scenario where X pays Y, and Y then pays B, would often be contrary to fairness (衡平 - kōhei), as the economic substance and Y's ultimate control over the fund's disposition can be similar.

The Crucial "Special Circumstances" Exception

However, the Supreme Court immediately qualified this general presumption with a critical exception: the presumption that the borrower (Y) has benefited is rebutted if "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō) exist.

Finding "Special Circumstances" in This Case

The Supreme Court found that the facts of this particular case clearly constituted such "special circumstances," leading to the conclusion that Y had received no benefit:

- No Relationship Between Borrower and Recipient: There was no pre-existing legal or factual relationship whatsoever between Y (the coerced borrower) and B (the third party who received the loan funds). B was effectively a stranger to Y.

- Pervasive Duress: Y had acted entirely under the duress exerted by A. This coercion extended not only to Y being forced to enter into the loan agreement with X in the first place but also, crucially, to Y being forced to instruct X to transfer the loan funds to B's bank account. Y had no independent will or interest in B receiving the money.

Given these specific facts, the Supreme Court concluded that Y had derived no benefit at all from X's disbursement of the loan funds to B. Y was merely a conduit for A's coercive scheme.

Therefore, X's alternative claim against Y for unjust enrichment failed. The High Court had erred in applying the general presumption of benefit to Y without adequately considering these overriding special circumstances that negated any actual enrichment on Y's part. While the Supreme Court did not explicitly state where X's unjust enrichment claim should now be directed, the strong implication is that if anyone was unjustly enriched by X's payment (assuming B had no legal cause to receive or retain the funds from X or via Y's coerced instruction), it would be B, the actual recipient of the money.

Dissecting Three-Party Unjust Enrichment

This 1998 Supreme Court ruling provides important clarification on applying unjust enrichment principles in "triangular relationships" (三角関係 - sankaku kankei), where a payment or benefit flows from one party (X, the lender) to another (B, the recipient) based on an instruction or underlying (but defective) relationship with an intermediary (Y, the borrower).

The General Approach and Its Limits

The Court established a general starting point: the party who instructs the disbursement (Y) is presumed to benefit. This simplifies matters for the payer (X), who doesn't have to unravel complex relationships between the other two parties. However, the "special circumstances" escape hatch is vital. It prevents this presumption from leading to unfair results where the instructing party was a mere victim of coercion and gained nothing.

The Significance of Duress and Lack of Connection

The two key elements that constituted "special circumstances" here were:

- The complete lack of any prior connection or obligation between the borrower (Y) and the person to whom the funds were paid (B). This meant Y wasn't, for example, satisfying their own debt or making a gift they intended.

- The fact that Y's instruction to pay B was itself a product of duress, just like the loan agreement itself. Y had no genuine intent for B to receive funds for Y's benefit.

Broader Implications for Multi-Party Disputes

This case underscores that in multi-party unjust enrichment scenarios, courts will look beyond the simple flow of funds. The underlying relationships (or lack thereof) and the validity of the instructions and contracts involved are critical. While the law often aims to channel restitution claims along the lines of direct contractual relationships (e.g., if X-Y is void, X claims from Y), this judgment shows that if Y demonstrably received no benefit due to coercion and lack of connection to the ultimate recipient, the chain of liability from X to Y can be broken. The lender (X) might then need to pursue the actual recipient (B) if B was enriched without cause.

Conclusion

The 1998 Japanese Supreme Court decision illustrates a careful balancing act in the law of unjust enrichment. While aiming for practical solutions by generally presuming that a party instructing a payment to a third party benefits from that payment (especially if their own contract with the payer is later voided), the Court carved out a crucial exception for "special circumstances." Where the instructing party acted entirely under duress and had no meaningful connection or independent reason for the third party to receive the funds, they are deemed not to have been unjustly enriched. This ensures that the doctrine, which is rooted in fairness, does not inadvertently penalize a party who was themselves a victim of coercion and derived no actual benefit from the transaction. It highlights the importance of a thorough factual inquiry into the relationships and pressures affecting all parties in complex, multi-party financial disputes.