Loan Shark Victims Don't Have to "Net Out" Principal from Damages: Japan's Supreme Court on Illegal Loans and "Illegal Cause Benefit"

Judgment Date: June 10, 2008

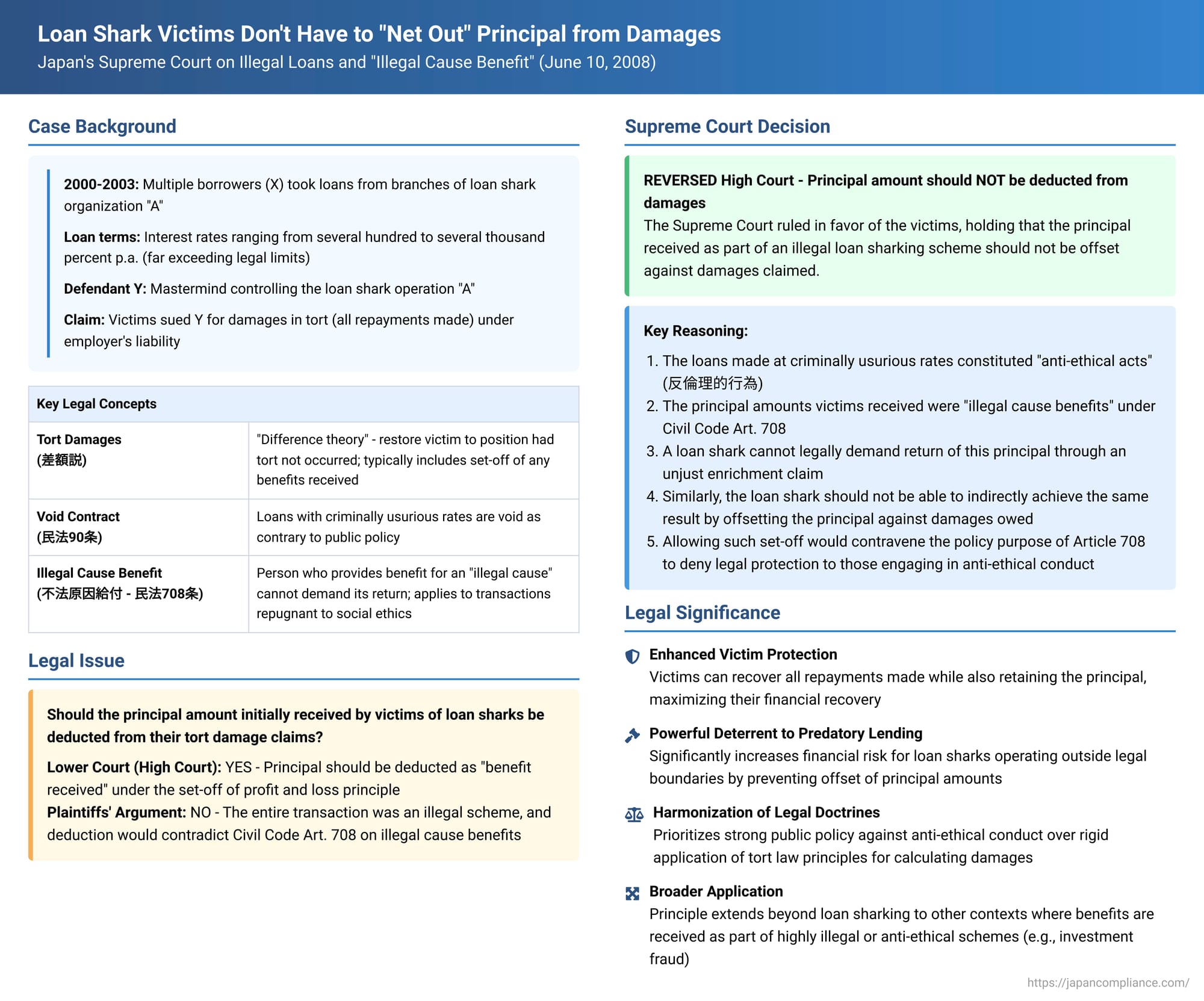

Loan sharking, known in Japan as "yamikin'yū" (ヤミ金融), involves lending money at exorbitantly high interest rates that far exceed legal limits, often accompanied by aggressive and illicit collection tactics. Victims of such predatory lending often find themselves in dire financial straits, having made substantial repayments that predominantly cover interest rather than reducing the principal. When these victims sue the loan sharks (or their principals) for damages in tort, a critical legal question arises: should the principal amount initially received by the borrower be deducted from the total damages claimed (typically the sum of all repayments made)? The Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, addressed this issue in a landmark decision on June 10, 2008 (Heisei 19 (Ju) No. 569), providing significant protection to victims of such "anti-ethical" financial practices.

The Predatory Lending Scheme and the Victims' Plight

The case involved multiple plaintiffs (collectively referred to as X) who had borrowed money from various branches of a loan sharking organization operating under the name "A" between November 2000 and May 2003. The defendant, Y, was the mastermind and controller of this organization, employing store managers and staff who engaged in these lending activities. The interest rates charged to X were astronomically high, ranging from several hundred to several thousand percent per annum, far exceeding the caps set by Japan's Interest Rate Restriction Act and even the criminal sanctions threshold under the (then-applicable) Act on Regulation of Receiving of Capital Subscription, Deposits and Interest on Deposits (the "Investment Law" or 出資法 - Shusshi Hō).

The plaintiffs argued that the "loans" they received from A's branches were not legitimate credit transactions but were merely a means used by the loan sharking operation to unlawfully extract exorbitant sums of money from them under the guise of principal and interest repayments. They contended that these actions constituted a tort (an unlawful act causing harm) and sued Y, as the principal and employer of those running the A operations, for damages under the doctrine of employer's liability (Civil Code Article 715). The damages claimed were essentially the total amounts they had repaid to the loan shark.

The Legal Doctrines at Play: Tort, Unjust Enrichment, and "Illegal Cause Benefit"

To understand the Supreme Court's decision, it's crucial to grasp three interconnected legal concepts:

- Tort Damages and the "Difference Theory" (差額説 - sagaku-setsu): In Japanese tort law, damages are generally calculated based on the "difference theory." This means the aim is to restore the victim to the financial position they would have been in had the tort not occurred. If, as part of the tortious transaction, the victim received some form of benefit (e.g., the principal amount of a loan in a fraudulent lending scheme), a strict application might suggest that this benefit should be deducted from the gross loss suffered by the victim. This is often conceptualized through the principle of "set-off of profit and loss" (損益相殺 - son'eki sōsai), where any gains to the victim arising from the tortious act are offset against their losses to determine the net compensable damage.

- Contracts Void Against Public Policy (Civil Code Article 90): Loan agreements with interest rates that are grossly extortionate, particularly those violating criminal statutes like the Investment Law, are typically considered void as being contrary to public policy and good morals (公序良俗違反 - kōjo ryōzoku ihan).

- "Illegal Cause Benefit" (不法原因給付 - fuhō gen'in kyūfu - Civil Code Article 708): This article is pivotal. It states that a person who provides a benefit (e.g., money, goods) for an "illegal cause" (不法な原因 - fuhō na gen'in) cannot demand its return as unjust enrichment. The term "illegal cause" is generally interpreted to mean acts that are not merely contrary to law but are significantly "anti-ethical" (反倫理的行為 - hanrinriteki kōi), i.e., repugnant to social ethics and morals. In the context of loan sharking, the principal amount lent by the loan shark at criminally usurious rates is considered a benefit provided for an illegal cause. Consequently, the loan shark (the giver) cannot legally sue the borrower to recover this principal. As a "reflexive effect" of this, the borrower (the recipient) is generally considered to acquire the right to retain this principal without an obligation to repay it, at least under the law of unjust enrichment.

The Lower Court's Approach: Allowing Set-Off of the Principal

The Takamatsu High Court, acting as the lower appellate court, found that Y was indeed liable as the principal for the tortious actions of the A loan sharking operation. The court acknowledged that A's conduct—contracting for and receiving interest at rates grossly exceeding the limits set by the Investment Law—was highly illegal and constituted a tort.

However, when calculating the damages payable by Y to the plaintiffs (X), the High Court applied the principle of "set-off of profit and loss." It ruled that the principal amounts X had originally received from A's branches should be deducted from the total sum of repayments X had made. This significantly reduced the amount of damages X could recover. The plaintiffs appealed this specific aspect of the High Court's decision—the deduction of the principal—to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Reversal: No Set-Off for Tainted Benefits

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision on the set-off issue and remanded the case for recalculation of damages without deducting the principal amounts X had received.

The Court's core reasoning was a direct application and prioritization of the policy behind Civil Code Article 708:

- Purpose of Article 708: The Supreme Court emphasized that Article 708, by denying the right to reclaim benefits provided for an illegal cause (specifically, an "anti-ethical act"), aims to make it clear that the law will not offer its protection or assistance to such morally reprehensible transactions.

- The Loan Principal as an "Illegal Cause Benefit": The Court affirmed that the loans made by A's branches to X at grossly usurious rates, with the intent to illegally extract exorbitant repayments, constituted "anti-ethical acts." Therefore, the principal amounts that X received as part of these loan transactions were benefits provided for an illegal cause.

- Direct Effect of Article 708: As a direct consequence of Article 708, the loan shark (A, and by extension Y) could not legally demand the return of this principal from X through an unjust enrichment claim.

- No Set-Off in Tort Damages – Upholding Article 708's Policy: This was the crucial step. The Supreme Court ruled that if a benefit received by the victim of an "anti-ethical" tort is itself an "illegal cause benefit" (which the perpetrator cannot reclaim), then that benefit cannot be deducted from the victim's damages in a tort claim through the mechanism of set-off of profit and loss or any similar profit-loss balancing adjustment.

- Rationale for Prohibiting Set-Off: To allow the loan shark to deduct the principal they "lent" as an integral part of their illegal and anti-ethical scheme from the damages they are ordered to pay would fundamentally contravene the purpose of Article 708. It would indirectly permit the perpetrator to benefit from their illegal act by reducing their ultimate liability. The law, having denied the loan shark the right to reclaim the principal directly, should not then allow them to achieve a similar result by offsetting it against the damages they owe for their wrongdoing.

In essence, the Supreme Court held that the policy objective of Article 708—to refuse legal assistance to those engaging in anti-ethical conduct—takes precedence over the general tort law principle of set-off of profit and loss when the "profit" in question is an illegal cause benefit. As a result, the victim (the borrower) is effectively allowed to retain the principal they received and can also claim damages from the loan shark for all amounts they subsequently repaid (whether those repayments were nominally for principal or the extortionate interest, as the entire transaction is tainted by the tortious scheme).

Justice Mutsuo Tahara, in a concurring opinion, agreed with the outcome but expressed some hesitation about a categorical rule that set-off is never allowed for illegal cause benefits, suggesting a need to consider specific circumstances. However, he ultimately concurred that in this loan sharking context, where the loan itself was void and an illegal cause benefit, all repayments made by the victims should be considered damages, and the initial principal received by them should not be offset.

Analyzing the Decision's Rationale, Scope, and Impact

This Supreme Court decision has significant implications for victims of loan sharking and other "anti-ethical" tortious conduct in Japan:

- Strengthened Protection for Victims: By disallowing the set-off of the principal in damage calculations, the ruling ensures that victims of loan sharking can recover a greater portion of the money extracted from them, effectively allowing them to keep the principal and recover all repayments. This brings the outcome of a tort claim in such cases closer to what might be achieved if the claim were framed purely in terms of unjust enrichment based on a void contract coupled with the non-recoverability of the illegal cause benefit by the lender.

- Deterrence of Predatory Lending: The decision significantly raises the financial stakes for loan sharks. Knowing that they cannot even offset the principal amounts they disbursed as part of their illegal schemes when sued for damages strengthens the deterrent effect against such predatory lending.

- When Does the "No Set-Off" Rule Apply? The key criterion appears to be that the initial "benefit" received by the victim (e.g., the loan principal) must itself be an integral component of an "anti-ethical act." The PDF commentary and the judgment's context suggest that this threshold is met when the underlying transaction (like a loan) is not merely contrary to civil law (e.g., exceeding IRRA interest limits but not criminal limits) but is so egregious that it violates criminal statutes (such as the Investment Law's then-applicable cap on interest rates, which, if grossly exceeded, characterized the lending as a criminal offense). Such transactions are considered not just partially void but wholly void against public policy and deeply repugnant to social ethics.

- Harmonizing Tort Law with Public Policy on Illegal Acts: The Supreme Court's ruling can be seen as an effort to harmonize the application of tort law principles with the strong public policy embodied in Civil Code Article 708. It prioritizes the objective of discouraging and refusing legal sanction to "anti-ethical" conduct over a rigid adherence to the traditional "difference theory" of damages or the principle of set-off of profit and loss, particularly when those doctrines would lead to a result that effectively aids or lessens the consequences for the perpetrator of the illegal act.

- Broader Applicability: The principle established in this case is not necessarily confined to loan sharking. As indicated by legal commentators and subsequent jurisprudence (e.g., a Supreme Court decision on June 24, 2008, concerning investment fraud), the rule that a "benefit" received by a victim as an integral part of the perpetrator's highly illegal or anti-ethical scheme should not be subject to set-off in a damages claim has broader potential application. For example, if a fraudster makes small, sham "dividend" payments to a victim to lure them into a larger fraudulent investment, those sham payments might not be deductible from the victim's ultimate damages claim for the larger sum lost.

This judgment represents a notable development in Japanese law, where the courts have shown a willingness to adapt general legal principles to address the severe societal harm caused by predatory practices like loan sharking, ensuring that the legal framework does not inadvertently provide relief or advantage to those who engage in such "anti-ethical" conduct.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's June 2008 decision in the loan sharking case is a powerful affirmation of protection for victims of highly illegal and unethical financial exploitation. By ruling that the principal amount "lent" by a loan shark as part of a criminally usurious scheme cannot be deducted from the damages owed to the victim, the Court reinforced the strong public policy against countenancing such predatory acts. This decision ensures that victims are not forced to effectively subsidize the loan shark's illegal enterprise by having the "tainted" principal set off against their rightful claims for repayments made under duress and deception. It marks a significant step in aligning the remedies available under tort law with the broader societal condemnation of "anti-ethical" transactions.