Life Insurance, Suicide Clauses, and Declaratory Judgments: A 2004 Supreme Court Ruling

Date of Judgment: March 25, 2004

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Introduction

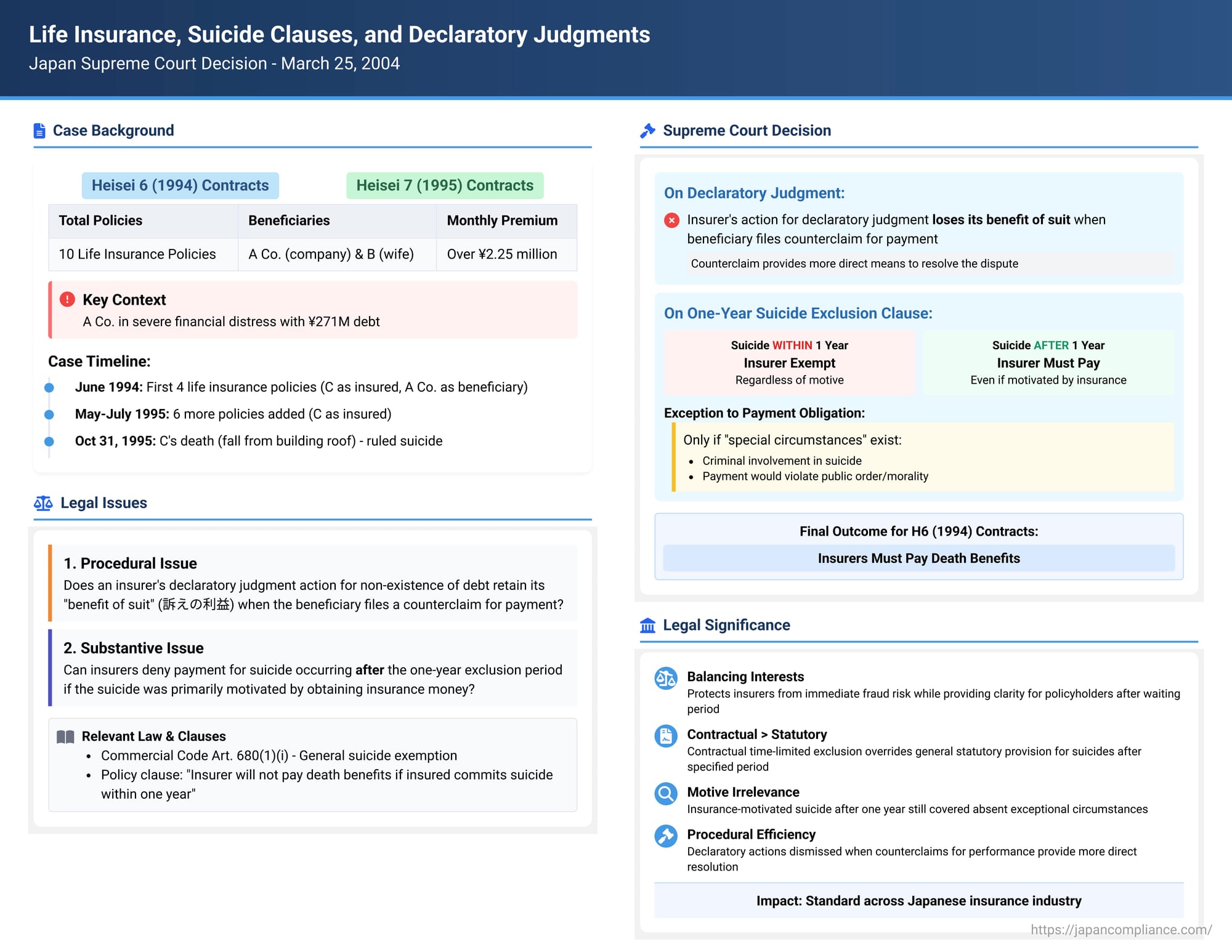

This article delves into a 2004 decision by the Supreme Court of Japan (Case Nos. Heisei 13 (O) No. 734 and Heisei 13 (Ju) No. 723), titled "Claim for Insurance Benefit, Main Action for Confirmation of Non-Existence of Debt, and Counterclaim for the Same." This complex case involves multiple life insurance policies and addresses two significant legal issues: first, the procedural question of whether a debtor's (in this case, an insurer's) action for a declaratory judgment confirming the non-existence of a debt retains its "benefit of suit" (訴えの利益 - uttae no rieki) if the creditor (the beneficiary) files a counterclaim for payment of the same debt. Second, and more substantively, it provides a crucial interpretation of "one-year suicide exclusion clauses" commonly found in life insurance policies in Japan, particularly concerning whether an insurer can still be exempted from payment if the insured's suicide after the one-year period was primarily for the purpose of obtaining insurance money.

Factual Background

The case involved a series of life insurance policies taken out on the life of C, the representative director of A Company (the first appellant, hereinafter "A Co."). C's wife, B (the second appellant), succeeded him as representative director after his death. The appellees were several life insurance companies (N Life, D Life, M Y Life, S Life, and A Life, hereinafter referred to by their anonymized initials or collectively as "the Insurers").

- Financial Situation of A Co.: A Co., established by C in July 1967 for waterproofing and construction work, had been facing increasing financial difficulties. By fiscal year 1994, its accumulated losses reached over 104 million yen, and its total borrowings were over 271 million yen. Its business condition around 1994 was described as considerably severe.

- Life Insurance Policies:

- "Heisei 6 Contracts": On June 1, 1994, A Co. entered into four life insurance contracts (Contracts 1-4 in the attached schedule of the original judgment) with N Life, D Life, M Y Life, and S Life (collectively "the Four H6 Insurers"). C was the insured, and A Co. was the beneficiary.

- "Heisei 7 Contracts":

- On May 1, 1995, A Co. entered into three more life insurance contracts (Contracts 5-7) with D Life, N Life, and M Y Life. On June 1, 1995, A Co. entered into another contract (Contract 8) with S Life. In all these, C was the insured and A Co. the beneficiary.

- On July 1, 1995, C himself entered into two life insurance contracts (Contracts 9-10) with M Y Life and A Life, naming his wife, B, as the beneficiary.

- Collectively, these ten contracts are referred to as the "Subject Life Insurance Contracts."

- Policy Terms: The applicable policy clauses for whole life and term life insurance stipulated that death benefits would be paid "when the insured dies." They also contained a special provision (the "One-Year Suicide Exclusion Clause") stating that the insurer would not pay death benefits if the insured committed suicide within one year from the insurer's commencement of liability.

- Additional Insurance and Premiums: Between August and September 1995, A Co. took out five accident insurance policies on C with multiple non-life insurers, with total benefits of 300 million yen. By July 1995, the total monthly premiums for the Subject Life Insurance Contracts alone amounted to 2,098,176 yen. By September 1995, when including premiums for other endowment and the new accident policies, the total monthly premium obligation for A Co. and C exceeded 2.25 million yen.

- C's Death: On October 31, 1995, C, after attending an interim inspection of a waterproofing repair project A Co. was undertaking on a multi-unit residential building, went alone to the rooftop of one of the buildings around 2:30 PM, fell from there, and died from spinal cord injuries and other trauma.

- Finding of Suicide: The lower courts, and ultimately the Supreme Court in its review of this point, found that C's death was a suicide. This conclusion was based on several factors: the numerous high-value insurance policies taken out by A Co. and C; A Co.'s severe financial distress making the continued payment of over 2 million yen in monthly premiums extremely difficult; and the lack of a rational explanation for C's actions leading to his death.

The Lawsuits

- First Action (H6 Contracts): A Co. sued the Four H6 Insurers (N Life, D Life, M Y Life, and S Life) for payment of death benefits under the Heisei 6 Contracts and delay damages.

- Second Action (Insurers' Declaratory Judgment): Five of the Insurers (D Life, N Life, M Y Life, S Life, and A Life – the "Five H7 Insurers") sued A Co. or B for a declaratory judgment confirming the non-existence of their obligation to pay death benefits under the main provisions of the Heisei 7 Contracts.

- Third Action (Beneficiaries' Counterclaim for H7 Contracts): In response to the Second Action, A Co. counterclaimed against D Life, N Life, M Y Life, and S Life for benefits under the Heisei 7 Contracts where it was the beneficiary. B counterclaimed against M Y Life and A Life for benefits under the Heisei 7 Contracts where she was the beneficiary.

(Claims for accidental death benefits under special riders were dismissed by the lower court and not appealed, so they were not before the Supreme Court.)

The Supreme Court's Reasoning and Decision

The Supreme Court's judgment addressed the procedural issue of the declaratory judgment suit first, then the substantive issue of the suicide exclusion clause for the Heisei 6 contracts.

1. Benefit of Suit for the Insurers' Declaratory Judgment Action (Second Action)

The Supreme Court, exercising its own initiative (shokken), addressed the procedural validity of the Five H7 Insurers' main suit (Second Action) seeking confirmation of non-existence of debt.

- Principle: The Court held that once the beneficiaries (A Co. and B) filed their counterclaims (Third Action) seeking payment of the insurance benefits under the Heisei 7 Contracts, the original suit by the Five H7 Insurers for a declaration of non-existence of these same insurance payment obligations lost its "benefit of confirmation" (確認の利益 - kakunin no rieki) and should be dismissed as improper (不適法 - futekihō).

- Rationale: A declaratory judgment action is permissible when there is a need to clarify a present legal uncertainty or risk to the plaintiff's legal position. However, when the creditor (the insured/beneficiary in this context) actively sues for performance of the alleged obligation (payment of insurance benefits), the issue of the debt's existence will be directly and definitively resolved in that performance action (the counterclaim). The counterclaim for payment provides a more direct and complete means of resolving the dispute than the insurer's original declaratory action. Therefore, the necessity for the insurers' separate declaratory judgment is extinguished.

- Disposition: Consequently, the parts of the lower appellate court's judgment dealing with the Five H7 Insurers' claims for confirmation of non-existence of debt under the Heisei 7 Contracts were quashed. The first instance judgment on these specific claims was annulled, and these particular lawsuits by the insurers were dismissed as improper.

2. Interpretation of the One-Year Suicide Exclusion Clause (First Action - H6 Contracts)

The core substantive issue was whether the Four H6 Insurers were liable under the Heisei 6 Contracts, given that C's suicide occurred after the one-year exclusion period stipulated in the policies had passed. The lower appellate court had ruled that even if the suicide occurred after one year, if the insurer could prove the suicide was solely or primarily for the purpose of obtaining insurance money, then Article 680, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Commercial Code (which generally exempts insurers from paying for death by suicide, without a time limit specified in the statute itself) would still apply, and the insurer would be exempt.

The Supreme Court disagreed with the lower appellate court's interpretation of the interplay between the statutory provision and the contractual one-year suicide exclusion clause:

- Purpose of Statutory Suicide Exclusion (Commercial Code Art. 680(1)(i)): The Court explained that the statutory provision exempting insurers for suicide is based on the idea that causing an insured event (death) intentionally by suicide violates the principle of good faith and fair dealing in an insurance contract. It also aims to prevent life insurance from being used for improper purposes (i.e., as a means to secure funds through suicide).

- Purpose of Contractual One-Year Suicide Exclusion Clauses: Life insurance policies commonly include clauses like the one-year suicide exclusion. The rationale for such time-limited exclusions is multifaceted:

- It is generally difficult to sustain a motive to commit suicide solely for insurance benefits over a long period (e.g., more than one year) from the time of contracting. Suicides occurring after a significant period are usually presumed to stem from motives unrelated to the initial insurance contract.

- It is extremely difficult to retrospectively determine the true motive or cause of a suicide.

- Therefore, these clauses aim to prevent the improper use of life insurance by providing a clear, albeit time-limited, rule: insurers are exempted for suicides within the specified period (e.g., one year) regardless of the motive or purpose for the suicide.

- Interpretation of the One-Year Clause's Effect After One Year: The Supreme Court held that if a policy contains a one-year suicide exclusion clause, this clause, by its nature, means that for suicides occurring after the one-year period:

- The insurer is generally obligated to pay the death benefit.

- The statutory provision of the Commercial Code (which provides a general suicide exclusion without a time limit) is displaced by the contractual agreement for suicides occurring after the one-year period.

- The insurer is not exempt from payment even if it can be proven that the insured's suicide after one year was motivated by the desire to obtain insurance money, UNLESS there are special circumstances, such as the involvement of criminal acts in the suicide or where paying the insurance benefit would violate public order and morality (kōjo ryōzoku).

- Validity of Such Contractual Clauses: The Court affirmed that such special clauses, which limit the insurer's exemption for suicide to a specific period, are valid agreements between the parties and take precedence over the general statutory provision for suicides occurring outside that period.

- Application to C's Suicide (H6 Contracts):

- C's suicide occurred more than one year after the Heisei 6 Contracts came into effect.

- Therefore, under the one-year suicide exclusion clause, the general suicide exclusion of the Commercial Code was inapplicable, and the insurers should, in principle, be liable for the death benefits.

- While A Co. was in severe financial distress, and C and A Co. had taken out numerous large insurance policies, there was no evidence of criminal acts involved in C's suicide, nor were there other circumstances suggesting that paying the insurance benefits would violate public order or morality.

- Even if C's primary motive for suicide was to enable A Co. and B to receive the insurance money, this did not constitute the "special circumstances" that would override the effect of the one-year exclusion clause (which implies payment for suicides after one year, regardless of insurance-procurement motive, absent public policy violations).

- Conclusion on H6 Contracts: The Supreme Court concluded that for the Heisei 6 Contracts, the insurers' obligation to pay the death benefits was not exempted by the statutory suicide provision due to the presence and effect of the one-year suicide exclusion clause. The lower appellate court's judgment, which had denied A Co.'s claim based on the reasoning that a suicide motivated by insurance fraud after one year could still be excluded under the Commercial Code, was an error in the interpretation and application of the law. This error clearly affected the judgment.

Final Judgment of the Supreme Court (Partially)

- The part of the original (appellate court) judgment concerning the First Action (A Co.'s claim under the Heisei 6 Contracts) was quashed, and this part of the case was remanded to the Tokyo High Court for further proceedings consistent with the Supreme Court's interpretation of the suicide exclusion clause.

- The parts of the original judgment concerning the Second Action (the Five H7 Insurers' main claims for confirmation of non-existence of debt under the Heisei 7 Contracts against A Co. and B) were quashed, and the first instance judgment on these parts was annulled.

- The lawsuits by the Five H7 Insurers in the Second Action were dismissed as improper (due to lack of benefit of suit after the counterclaims were filed).

- The appellants' (A Co. and B's) remaining appeals (concerning their claims under the Heisei 7 Contracts, which were dismissed by the lower court based on the suicide occurring within the one-year exclusion period for those specific later contracts, and for which leave to appeal was not granted on the merits of that point) were dismissed.

- Court costs were allocated accordingly.

Significance and Implications

This 2004 Supreme Court decision has several important implications:

- Confirmation of Non-Existence of Debt and Counterclaims: The judgment affirms the principle that a plaintiff's (debtor's) suit for a declaration of non-existence of debt generally loses its "benefit of suit" and becomes procedurally improper once the defendant (creditor) files a counterclaim for the performance of that same debt. The counterclaim for performance is seen as a more direct and comprehensive way to resolve the dispute.

- Interpretation of One-Year Suicide Exclusion Clauses in Life Insurance: This is the most significant substantive aspect of the ruling. The Supreme Court clarified that:

- A standard one-year suicide exclusion clause in a life insurance policy means that if the insured commits suicide within one year of the policy's inception, the insurer is exempt from paying death benefits, irrespective of the motive for the suicide.

- Conversely, if the insured commits suicide after one year from the policy's inception, the insurer is generally obligated to pay the death benefit. The statutory provision in the Commercial Code (which provides a general suicide exclusion without a time limit) is effectively overridden by such a contractual clause for suicides occurring after the one-year period.

- The insurer cannot deny payment for a suicide occurring after one year solely on the grounds that the suicide was motivated by the desire to obtain insurance money, unless there are exceptional circumstances, such as criminal involvement or a violation of public order and morality. The mere motive of securing insurance funds for beneficiaries, in the absence of such egregious factors, does not constitute these "special circumstances" after the one-year period has passed.

- Balancing Insurer Protection and Policyholder Expectations: This interpretation strikes a balance. The one-year clause protects insurers from claims arising from suicides planned around the time of policy inception for fraudulent purposes. After one year, the presumption shifts, and the insurer is generally expected to pay, reflecting the policyholder's expectation of coverage unless truly exceptional public policy concerns arise.

- Clarity for Insurance Practice: The decision provides greater clarity for insurers and policyholders regarding the application of suicide exclusion clauses, particularly for suicides occurring after the initial exclusion period. It limits the insurer's ability to deny claims based solely on the alleged motive of the insured if the suicide occurs outside the contractually defined exclusion period and no overriding public policy concerns are present.

This judgment is a key reference for understanding the procedural dynamics of declaratory judgment actions when counterclaims for performance are filed and provides a definitive interpretation of the widely used one-year suicide exclusion clause in Japanese life insurance contracts.