Life Insurance Payouts to Heirs: A Japanese Supreme Court Case on Fairness in Estate Division

Date of Decision: October 29, 2004

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Case No. 11 (kyo) of 2004 (Appeal against a High Court modification decision in an estate division and contributory portion determination case)

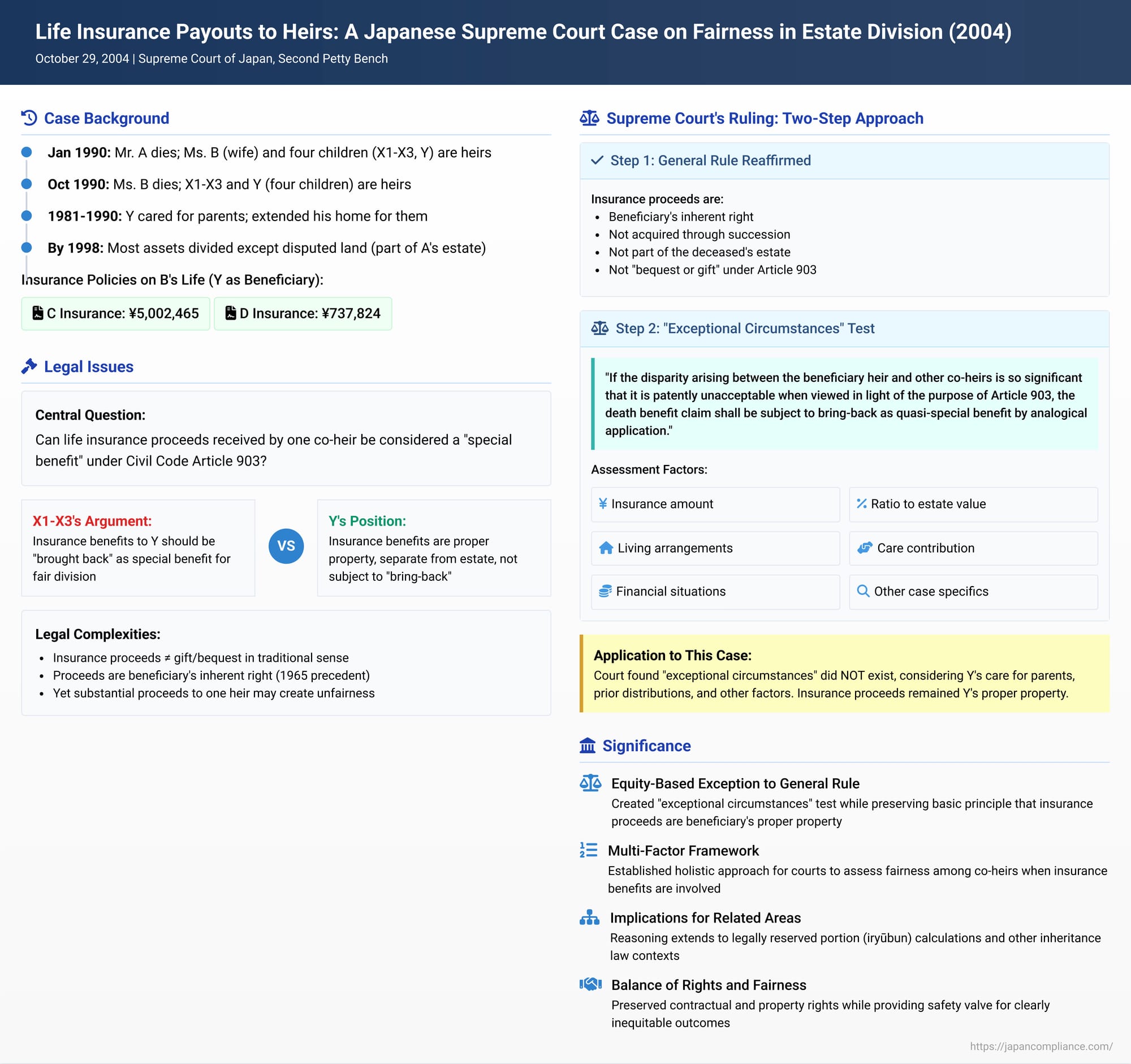

Life insurance is a common tool for financial planning, often intended to provide for loved ones after one's passing. In Japan, as in many jurisdictions, a death benefit paid to a specifically named beneficiary, even if that beneficiary is an heir, is generally considered the beneficiary's own inherent property, separate from the deceased's inheritable estate. This principle is well-established. However, what happens when this rule leads to outcomes that seem inequitable among co-heirs? A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on October 29, 2004, addressed this tension, carving out an exception to the general rule based on considerations of fairness.

The Factual Matrix

The case involved the estates of Mr. A and his wife, Ms. B. Mr. A passed away in January 1990, and Ms. B followed in October 1990[cite: 1]. The statutory heirs of Ms. B were their four children: X1, X2, X3 (the appellants), and Y (the respondent), each entitled to a one-fourth share[cite: 1]. Mr. A's heirs were Ms. B and their four children[cite: 1].

For many years, Mr. A had required significant care. From around 1981, he needed assistance with all aspects of daily life[cite: 1]. To provide this care, Ms. B quit her job in September 1981[cite: 1]. Around June 1981, Y, one of the children, extended his own home to create a separate living space for his parents, A and B, where they resided until their respective deaths[cite: 1]. Y also assisted Ms. B in caring for Mr. A[cite: 1]. During this period, the other children, X1, X2, and X3, did not live with A and B[cite: 1].

By 1998, X1-X3 and Y had already divided most of A's and B's assets (excluding a specific piece of land, "the land in question") through mutual agreements and court-mediated settlements[cite: 1]. As a result of these prior divisions, each child had received property valued between approximately 11.99 million yen and 14.41 million yen[cite: 1]. The legal proceedings leading to the Supreme Court decision, initiated around 1995 for A's estate and 1998 for B's, eventually focused solely on the division of "the land in question," which was part of A's estate and used by Y for his home and business[cite: 1].

The Family Court, in its initial substantive ruling (the "lower-lower court"), had decided that Y should receive the land in question and, in return, pay monetary compensation to X1, X2, and X3[cite: 1]. This ruling was made on the premise that certain life insurance proceeds Y had received constituted a "special benefit" to him[cite: 1]. These insurance policies were:

- An endowment policy from C Insurance, with B as the policyholder and insured, and Y as the death beneficiary. The contract was dated March 1, 1990, and the death benefit was 5,002,465 yen[cite: 2].

- An endowment policy from D Insurance, also with B as the policyholder and insured, and Y as the death beneficiary. This contract was dated October 31, 1964, and the death benefit was 737,824 yen[cite: 2].

(A third policy, a mutual aid (kyosai) contract with E Agricultural Cooperative, where A was the policyholder and beneficiary and B was the insured, was also mentioned, but the Supreme Court deemed it not relevant for the core legal discussion on special benefits by analogical application, as the beneficiary was the policyholder himself.)

The appellants (X1-X3) appealed to the High Court. The High Court dismissed the case concerning B's estate, finding no assets left to divide[cite: 1]. Regarding A's estate, it determined that only the insurance proceeds received by Y were at issue as a potential special benefit[cite: 1]. The High Court, largely quoting a previous Supreme Court decision (from 2002), ruled that these insurance proceeds did not qualify as a bequest or a gift of capital for living expenses under Article 903, paragraph 1, of the Civil Code[cite: 1]. Consequently, it ordered that Y should obtain sole ownership of the land (valued at 11.49 million yen) and pay each of X1, X2, and X3 one-fourth of this value as compensation, without factoring in the insurance proceeds as a special benefit to Y[cite: 1].

Dissatisfied, X1, X2, and X3 sought and obtained permission to appeal to the Supreme Court, specifically challenging the High Court's general denial of the special benefit nature of death insurance proceeds[cite: 1].

The Legal Dilemma: Insurance as a "Special Benefit"?

Under Japanese inheritance law, Article 903 of the Civil Code addresses the concept of "special benefits." This provision generally requires that if an heir has received a gift from the deceased during their lifetime for the purpose of marriage, adoption, or as capital for maintaining a livelihood, or has received a bequest, the value of such a benefit should be added back to the value of the deceased's estate at the time of death. This "bring-back" or "clawback" mechanism is designed to calculate the shares for each heir fairly, ensuring that such lifetime advancements are accounted for.

However, a long-standing principle in Japanese law, affirmed by a Supreme Court decision in 1965 (Showa 40.2.2)[cite: 2], is that death benefit insurance proceeds received by a designated beneficiary are acquired as the beneficiary's own inherent right. They are not considered to be succeeded from the policyholder or insured, nor do they form part of the deceased's inheritable estate[cite: 2]. This created a conflict: if insurance proceeds are not part of the estate and not a "gift or bequest" in the traditional sense, how could potential unfairness among co-heirs—where one heir receives substantial insurance benefits while others do not—be addressed within the framework of equitable estate division?

The Supreme Court's Two-Step Approach (Decision of October 29, 2004)

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by X1-X3, upholding the High Court's conclusion but on a significantly more nuanced legal basis[cite: 2]. It established a two-step approach:

Step 1: The General Rule Reaffirmed

The Court began by reaffirming the established legal principles:

- A death benefit claim based on an endowment insurance contract where the deceased was the policyholder and insured, and a co-heir was designated as the beneficiary, is acquired by that beneficiary as their own inherent right[cite: 2]. It is not obtained through succession from the policyholder or insured and is not part of their inheritable estate[cite: 2]. (The Court cited its 1965 decision for this point, though it notably omitted the phrase "simultaneously with the insurance contract taking effect" found in the 1965 ruling, possibly to align with a 2002 Supreme Court decision (Heisei 14.11.5) which stated that the death benefit claim arises only when the insured dies [cite: 3, 2]).

- Furthermore, a death benefit claim arises only upon the death of the insured. It is not in an equivalent value relationship with the premiums paid by the policyholder, nor is it a substitute for the insured's earning capacity[cite: 2]. Therefore, it cannot be considered as property that substantially belonged to the policyholder or insured[cite: 2].

- Based on these premises, the Court concluded that such death insurance proceeds acquired by a beneficiary heir do not fall under the category of property received by "bequest or gift" as stipulated in Article 903, paragraph 1, of the Civil Code[cite: 2]. This is the general rule.

Step 2: The "Exceptional Circumstances" Caveat – Analogical Application of Article 903

This is where the Court introduced a groundbreaking qualification. It stated:

"However, considering that the premiums, which are the cost for acquiring the said death benefit claim, were paid by the deceased during their lifetime, and that the death benefit claim arises for the beneficiary heir upon the death of the deceased policyholder, if the disparity arising between the beneficiary heir and other co-heirs is so significant that it is patently unacceptable when viewed in light of the purpose of Article 903 of the Civil Code, it is appropriate to construe that, by analogical application of the said article, the said death benefit claim shall be subject to bring-back as quasi-special benefit." [cite: 2]

To determine whether such "exceptional circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō) exist, rendering the disparity "patently unacceptable," the Court laid out a comprehensive, multi-factor test. The following should be considered holistically:

- The amount of the insurance benefit received[cite: 2].

- The ratio of this insurance amount to the total value of the deceased's estate[cite: 2].

- The relationship between the beneficiary heir, other co-heirs, and the deceased. This includes factors such as:

- Whether they lived together[cite: 2].

- The degree of contribution to the deceased's care[cite: 2].

- The living situations and financial realities of each co-heir[cite: 2].

- Any other relevant circumstances of the particular case[cite: 2].

Application to the Case at Hand

Applying this newly articulated test to the facts concerning the insurance policies on Ms. B's life (where B was the policyholder/insured and Y was the beneficiary), the Supreme Court concluded that "exceptional circumstances" warranting the bring-back of the insurance proceeds did not exist[cite: 2].

The Court considered:

- The amounts of the insurance benefits Y received from these policies (approx. 5 million yen and 0.73 million yen)[cite: 2].

- The value of the land in question (the only asset from A's estate remaining for division, valued at approx. 11.49 million yen)[cite: 2].

- The apparent total value of Ms. B's estate (inferred from the prior distributions where each heir, including Y, had already received substantial assets from A's and B's estates)[cite: 2].

- The relationships between X1-X3, Y, and their parents A and B (notably Y's long-term cohabitation with and care for A and B)[cite: 2].

- The living situations of X1-X3 and Y as presented in the case[cite: 2].

Weighing these factors, the Court found that the imbalance caused by Y receiving the insurance proceeds was not so markedly unjust as to trigger the analogical application of Article 903[cite: 2]. (The Court also seemed to frame its analysis of these specific insurance policies as potential special benefits from Ms. B's estate, given she was the policyholder and insured for them [cite: 2]).

Elaborating on the "Exceptional Circumstances" Test

The "exceptional circumstances" test introduced by the 2004 Supreme Court decision is significant because it attempts to inject a degree of equitable consideration into a previously more rigid rule[cite: 3]. It acknowledges that while the principle of insurance proceeds being an inherent right of the beneficiary is sound, its strict application can sometimes clash with the underlying goal of Article 903, which is to achieve fairness among co-heirs.

The test is fact-intensive and requires a holistic evaluation. Legal commentary following the decision has noted that, in practice, lower courts have often placed particular emphasis on the absolute amount of the insurance payout and, critically, its proportion relative to the total value of the decedent's estate when assessing if a disparity is "patently unacceptable"[cite: 3].

Interestingly, the factors listed by the Supreme Court for determining "exceptional circumstances" bear a resemblance to the considerations involved when a court determines whether a deceased person implicitly expressed an intention to exempt a lifetime gift from being brought back under Article 903, paragraph 3 (known as "exemption from bring-back" or mochimodoshi no menjo no ishi hyōji)[cite: 3, 4]. The process of inferring such an exemption has itself been criticized by some scholars for potentially leading to an over-attribution of intent to the deceased and for a lack of predictability[cite: 4]. Similar challenges in predicting outcomes might arise with the "exceptional circumstances" test, given its broad, multi-factor nature[cite: 4].

It's also worth noting that the decision generally contemplates the bring-back of the actual insurance benefit amount received, not necessarily just the sum of premiums paid by the deceased[cite: 3].

Broader Implications: Connection to Iryūbun (Legally Reserved Portion)

The principles laid down in this 2004 decision, though directly addressing special benefits in the context of estate division, may also have implications for the calculation of the iryūbun, or the "legally reserved portion" of an estate[cite: 4]. Iryūbun is a statutory right for certain heirs (typically a spouse, children, or lineal ascendants) to receive a minimum share of the deceased's property, even if a will attempts to disinherit them or leave them a smaller share.

The question arises: if death benefits paid to a co-heir can, under exceptional circumstances, be treated like a special benefit for estate division, can they also be added to the calculation base for iryūbun? Legal scholarship suggests that this is a complex area. If the insurance beneficiary is a non-heir, the 2002 Supreme Court ruling (which found that changing a beneficiary from an heir to a non-heir was not akin to a gift affecting iryūbun) might still directly apply[cite: 4]. However, if the beneficiary is one of the co-heirs, the situation is different[cite: 4]. Article 1044, paragraph 3 of the Japanese Civil Code (both before and after the 2018 inheritance law reforms) establishes a link between special benefits made to co-heirs and the calculation of the iryūbun base[cite: 4]. Through this linkage, the reasoning of the 2004 Supreme Court decision could potentially extend to iryūbun calculations[cite: 4]. This becomes particularly relevant in scenarios where a will disposes of all estate assets, leaving no property for traditional estate division (the usual forum for special benefit calculations), making the iryūbun claim the primary avenue for heirs to seek their due[cite: 4].

Post-2004 lower court decisions involving iryūbun claims and death insurance benefits have been numerous[cite: 4]. In cases where the beneficiary was a co-heir, relatively few have resulted in the insurance proceeds being added to the iryūbun calculation base[cite: 4]. However, some decisions have affirmed such an addition[cite: 4]. These affirmative cases often share characteristics such as:

- The insurance amount being very large, especially in proportion to the other estate assets[cite: 4].

- The life insurance policy having been concluded only a few years before the deceased's death, with premiums paid in a lump sum[cite: 4]. In such instances, the insurance policy functions very similarly to a cash deposit, making the argument for treating it as part of the deceased's financial legacy more compelling[cite: 4]. Some analyses suggest that these cases could almost be viewed as a bring-back of the premium amount, given the close equivalence between premium paid and benefit received in such scenarios[cite: 4].

Significance of the 2004 Ruling

The Supreme Court's October 29, 2004 decision represents a nuanced evolution in Japanese inheritance and insurance law.

- It carefully preserves the fundamental principle that life insurance proceeds paid to a named beneficiary are their inherent right.

- However, it introduces a vital exception, rooted in equity, allowing for these proceeds to be treated as a special benefit under Article 903 of the Civil Code by analogical application if "exceptional circumstances" lead to a "patently unacceptable" disparity among co-heirs.

- It provides a flexible, multi-factor framework for courts to assess such disparities, aiming to achieve fairness without unduly disrupting established contractual and property rights.

- The ruling, while specific to endowment insurance in its facts, is generally understood to apply to life insurance more broadly[cite: 3].

Concluding Thoughts

This 2004 Supreme Court decision marks a significant step towards balancing the contractual nature of life insurance with the overarching principles of fairness in inheritance. While the bar for invoking the "exceptional circumstances" test is set high, its existence provides a crucial safety valve to address situations where a rigid application of general rules would lead to profoundly inequitable outcomes among heirs. The decision underscores a continuing effort within Japanese jurisprudence to adapt long-standing legal doctrines to ensure they meet contemporary standards of justice and equity in complex family and financial matters.