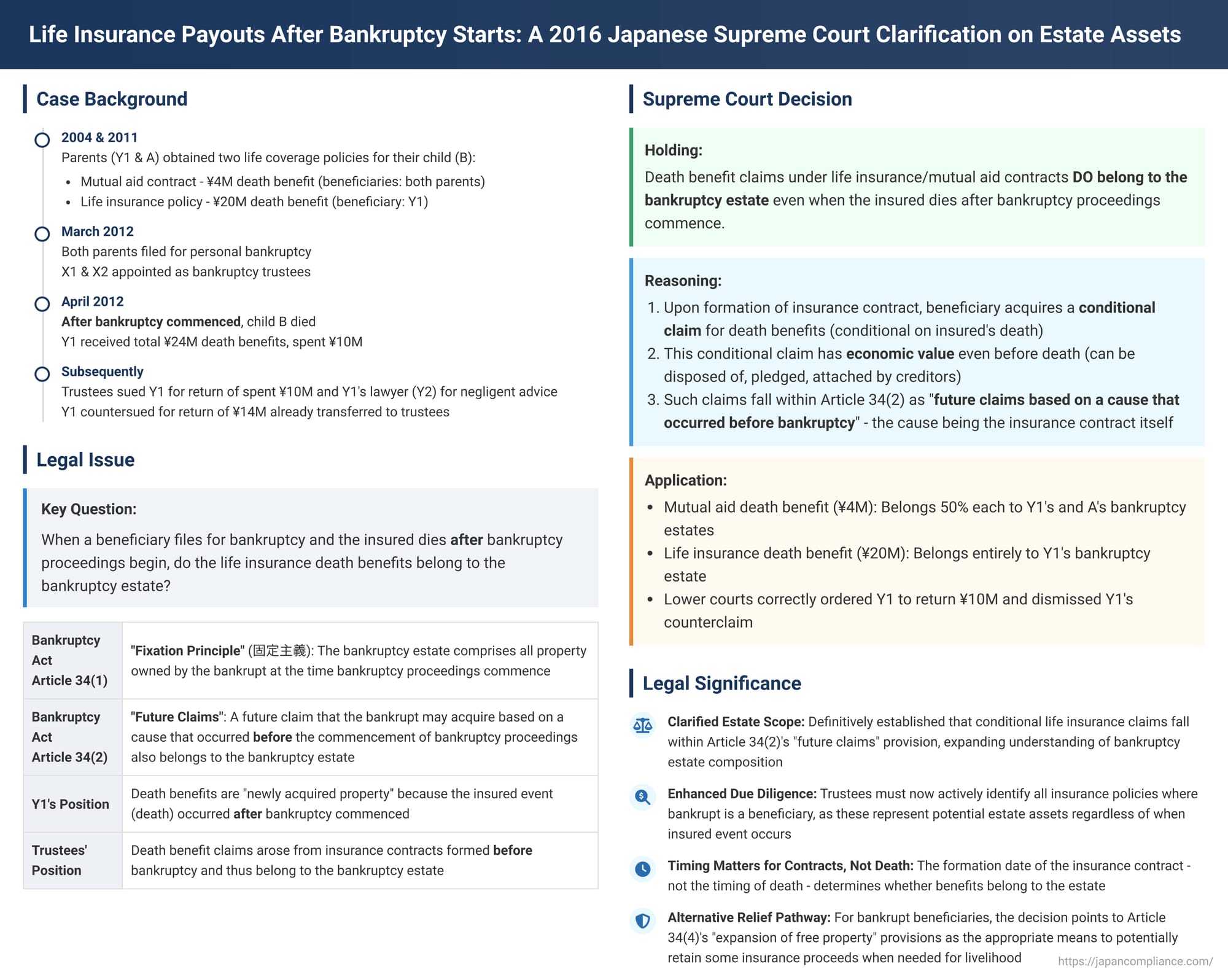

Life Insurance Payouts After Bankruptcy Starts: A 2016 Japanese Supreme Court Clarification on Estate Assets

On April 28, 2016, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued an important judgment clarifying whether death benefit claims under life insurance or life mutual aid contracts belong to a beneficiary's bankruptcy estate if the insured person dies after the beneficiary's bankruptcy proceedings have commenced. The Court affirmed that such claims indeed form part of the bankruptcy estate, categorizing them as "future claims based on a cause that occurred before the commencement of bankruptcy proceedings" under Article 34, paragraph 2, of the Bankruptcy Act.

Factual Scenario: Insurance Policies, Bankruptcy, and a Post-Bankruptcy Death

The case involved parents, Y1 and A, whose child, B, was the subject of two life coverage policies:

- A life mutual aid contract with C Mutual Aid Federation, established in 2004, covering B with a death benefit of 4 million yen. The designated beneficiaries were Y1 and A.

- A life insurance contract with D Life Insurance Co., established in 2011, insuring B with a death benefit of 20 million yen. The designated beneficiary for this policy was Y1.

In March 2012, both Y1 and A filed for personal bankruptcy, and the Tokyo District Court commenced bankruptcy proceedings for each of them. X1 and X2 (who were the same lawyer) were appointed as their respective bankruptcy trustees.

Tragically, in April 2012—after the bankruptcy proceedings for Y1 and A had started—their child, B, passed away. Subsequently, Y1 processed the claims for both policies and received a total of 24 million yen in death benefits. Y1 then spent 10 million yen of these proceeds, partly on the advice of Y1's lawyer, Y2. The remaining 14 million yen was later transferred by Y1 into a trust account managed by the bankruptcy trustees (X1/X2).

The trustees, X1 and X2, asserting that the death benefit claims rightfully belonged to the bankruptcy estates of Y1 and A, filed a lawsuit. They sued Y1 for the return of the 10 million yen spent (on grounds of unjust enrichment) and sued Y2 (Y1's lawyer) for damages due to professional negligence in advising Y1 to spend funds that allegedly belonged to the estate. The trustees sought approximately 8 million yen for Y1's estate and 2 million yen for A's estate, to be paid jointly and severally by Y1 and Y2. In response, Y1 filed a counterclaim against trustee X1, demanding the return of the 14 million yen that had already been transferred to the trustee's account, arguing the funds were not part of the bankruptcy estate.

Both the first instance court and the High Court ruled largely in favor of the trustees. They found that the death benefit claims did belong to the bankruptcy estates of Y1 and A, and consequently upheld the trustees' main claims against Y1 and (in part) against Y2, while dismissing Y1's counterclaim. Y1 and Y2 then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Framework: "Fixation Principle" vs. "Future Claims" in Bankruptcy

The core legal issue revolved around the scope of the bankruptcy estate as defined by Japan's Bankruptcy Act.

- Article 34, paragraph 1, of the Act establishes the "fixation principle" (固定主義 - kotei shugi). This principle generally dictates that the bankruptcy estate comprises all property owned by the bankrupt individual at the precise time their bankruptcy proceedings commence. Property acquired by the bankrupt after this point is typically considered "newly acquired property" (新得財産 - shintoku zaisan) and does not form part of the bankruptcy estate, instead remaining the bankrupt's "free property" (自由財産 - jiyū zaisan).

- However, Article 34, paragraph 2, provides a crucial clarification and, in effect, an expansion of this principle. It states that "a future claim that the bankrupt may acquire based on a cause that occurred before the commencement of bankruptcy proceedings" also belongs to the bankruptcy estate. This provision is designed to capture assets like conditional claims or expectancies where the legal foundation for the claim was laid before bankruptcy, even if the claim itself only materializes or becomes payable after bankruptcy begins.

The central question for the Supreme Court was whether a beneficiary's contingent right to a death benefit under a life insurance policy existing pre-bankruptcy qualifies as such a "future claim" under Article 34, paragraph 2, when the insured event (death) occurs post-bankruptcy commencement.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Death Benefit Claim Belongs to the Estate

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by Y1 and Y2, affirming the lower courts' findings that the death benefit claims were indeed part of the bankruptcy estates.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Nature of a Beneficiary's Right to Death Benefits: Citing its own precedent from 1965, the Court reiterated that the beneficiary of a life insurance policy taken out for a third party acquires, upon the formation of the insurance contract, a claim for the death benefit. This claim is conditional upon the death of the insured occurring within the term specified in the contract.

- Pre-Death Value and Disposability: Importantly, the Court noted that even before the death of the insured, this conditional claim held by the beneficiary is not a mere expectancy devoid of legal character. It can be disposed of by the beneficiary (e.g., assigned or pledged, subject to policy terms) and can also be subject to attachment by the beneficiary's general creditors. This signifies that the conditional claim possesses a discernible economic value prior to the insured event.

- Application of Bankruptcy Act Article 34(2): Given these characteristics, the Supreme Court concluded that a death benefit claim held by a bankrupt beneficiary, arising from a life insurance contract that was validly concluded before the commencement of that beneficiary's bankruptcy proceedings, squarely falls under the definition of "a future claim that the bankrupt may acquire based on a cause that occurred before the commencement of bankruptcy proceedings" as stipulated in Article 34, paragraph 2, of the Bankruptcy Act. The "cause that occurred before commencement" is the insurance contract itself.

- Conclusion on Estate Inclusion: Consequently, such death benefit claims belong to the bankruptcy estate of the beneficiary. In this specific case, because both the life mutual aid contract and the life insurance contract were established before Y1 and A's bankruptcy proceedings began, the Court affirmed that the mutual aid death benefit claim belonged to Y1's and A's respective bankruptcy estates in one-half shares each, and the life insurance death benefit claim belonged entirely to Y1's bankruptcy estate. An earlier 1995 Supreme Court decision cited by the appellants was found to be inapplicable to the facts of the present case.

Addressing Counterarguments and Practical Considerations

Legal scholarship and practitioners have sometimes raised arguments against including such contingent insurance proceeds in the bankruptcy estate, citing factors like the low probabilistic value of the claim before the insured's death, potential hardship for a bankrupt beneficiary who might rely on such funds for their fresh start, and the risk of prolonging bankruptcy proceedings while waiting for the insured event to occur (or not).

The Supreme Court's decision, supported by legal commentary, suggests that these concerns, while valid, are often better addressed through other flexible mechanisms within the Bankruptcy Act rather than by excluding such claims from the estate outright:

- Trustee's Discretion: Bankruptcy trustees have discretion to manage estate assets, which can include abandoning claims that have very little value or where pursuit would be uneconomical.

- Expansion of "Free Property": For individual bankrupts, Article 34, paragraph 4, of the Bankruptcy Act allows the court, upon petition by the bankrupt, to issue an order expanding the scope of their "free property" (自由財産の拡張 - jiyū zaisan no kakuchō). This means that even if an asset (like an insurance claim) technically belongs to the estate, the court can permit the bankrupt to retain it, or a portion of it, if deemed necessary for maintaining their livelihood or facilitating their economic rehabilitation, taking into account their specific circumstances and the needs of their dependents. This provides a case-by-case avenue for addressing potential hardship.

Implications for Bankruptcy Trustees and Beneficiaries

This Supreme Court ruling has clear implications:

- Trustees' Due Diligence: Bankruptcy trustees must make efforts to identify any life insurance or mutual aid policies where the bankrupt individual is a named beneficiary, as these represent potential (albeit conditional) assets of the estate. This requires thorough investigation beyond typical asset schedules.

- Management of Conditional Claims: Trustees need to carefully assess and manage these conditional claims, considering factors like the likelihood of the insured event, the potential payout, any ongoing premium obligations, and the overall benefit to the estate versus the cost or delay of pursuing them.

- Awareness for Bankrupt Beneficiaries: Individuals undergoing bankruptcy who are beneficiaries of life insurance policies should be aware that their future entitlement to death benefits (if the policy existed before their bankruptcy) may be considered part of their bankruptcy estate if the insured event occurs. They may need to discuss options like applying for an expansion of free property with their legal advisors.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 2016 decision brings important clarity to the treatment of death benefit claims in the bankruptcy of a beneficiary in Japan. By firmly placing such claims within the scope of Article 34, paragraph 2, of the Bankruptcy Act, the Court reinforced the principle that the bankruptcy estate includes not only present assets but also future entitlements rooted in pre-bankruptcy causes. While this broadens the potential asset pool for creditors, the ruling also implicitly acknowledges that the Japanese bankruptcy system contains other provisions, such as the expansion of free property, to balance the interests of creditors with the bankrupt individual's need for a genuine fresh start.