Life Insurance and Tort Damages: A 1964 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on "Double Dipping"

Date of Judgment: September 25, 1964

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Case No. 328 (o) of 1964 (Damages Claim Case)

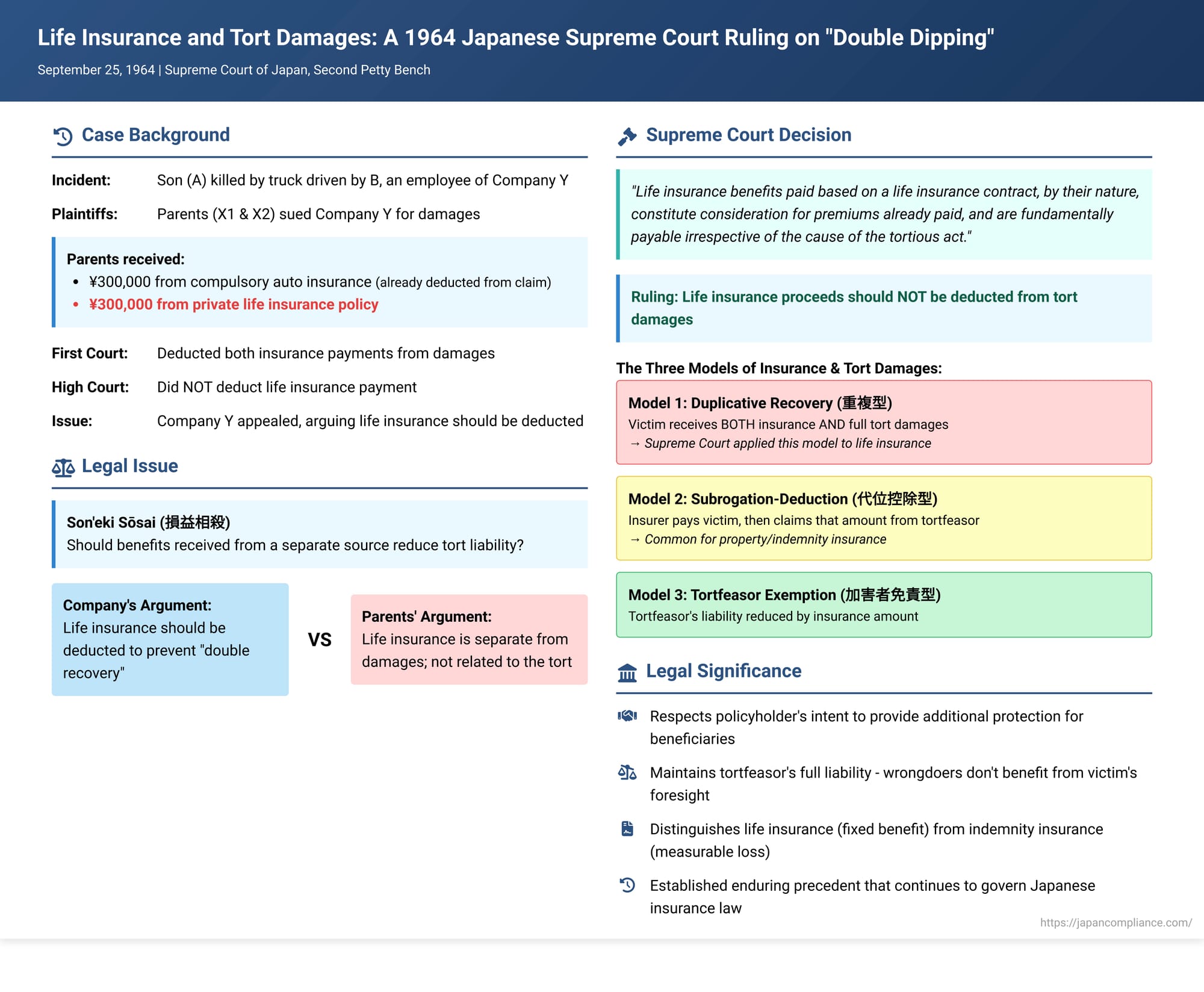

When a person's death is caused by the wrongful act of another (a tort), the deceased's heirs are generally entitled to claim damages from the tortfeasor. These damages can cover lost future earnings, funeral expenses, emotional distress, and more. A complex legal question arises, however, if the heirs also receive proceeds from a life insurance policy taken out on the deceased's life. Should these life insurance benefits be deducted from the amount of damages the tortfeasor is required to pay? This issue, touching upon the legal principle of son'eki sōsai (損益相殺 – set-off of benefits or compensatio lucri cum damno), was definitively addressed by the Supreme Court of Japan in a landmark decision on September 25, 1964.

The Tragic Event and Initial Rulings: Facts of the Case

The plaintiffs, X1 and X2, were the parents of A, who was tragically killed when he was struck by a small freight truck driven by B. B was an employee of Y company (the defendant and appellant). X1 and X2 filed a lawsuit against Y, as B's employer, seeking damages under Japan's Automobile Liability Security Act (自賠法 - jibaishōhō). Their claim included compensation for A's lost future earnings (an asset they inherited), medical expenses they incurred, funeral costs, and solatium for their emotional suffering. From this total, they had already deducted 300,000 yen received from compulsory automobile liability insurance.

The first instance court (Hakodate District Court) calculated A's lost earnings at a lower figure than claimed. More significantly for this appeal, it noted that X1 and X2 had not only received the 300,000 yen from the compulsory auto insurance but had also received an additional 300,000 yen from a life insurance policy on A's life where they were named as beneficiaries. The District Court held that, due to the "principle of subrogation from insurance benefits," X1 and X2 had effectively lost their right to claim damages from Y up to the combined sum of 600,000 yen (300,000 from auto insurance plus 300,000 from life insurance). After also finding A contributorily negligent and applying a reduction for comparative negligence, the court ordered Y to pay X1 and X2 a total of 343,056 yen.

Both X1 and X2, and Y company, appealed this decision. The Sapporo High Court (Hakodate Branch) dismissed Y's appeal and largely sided with X1 and X2 on the quantum of damages (before accounting for A's contributory negligence). It ordered Y to pay 550,000 yen to X1 and 500,000 yen to X2 after applying comparative negligence. Critically, the High Court made no mention of the 300,000 yen private life insurance proceeds and did not deduct this amount from the damages awarded to X1 and X2.

Y company appealed this High Court ruling to the Supreme Court. One of its main grounds for appeal was that the High Court had acted illegally by failing to deduct the 300,000 yen in life insurance proceeds that X1 and X2 had received.

The Legal Principle: Son'eki Sōsai (Set-Off of Benefits)

The legal principle at the heart of this dispute is son'eki sōsai. Generally, this principle states that if a claimant suffers damage but, as a result of the same event or cause that led to the damage, also receives some form of benefit, that benefit should be deducted from the total amount of damages awarded. This is to prevent the claimant from being "unjustly enriched" or overcompensated. While there is no explicit provision for son'eki sōsai in the Japanese Civil Code for torts, its application has been developed through case law and legal doctrine.

Modern legal terminology sometimes distinguishes between a strict son'eki sōsai (where the benefit arises from the very same cause as the loss) and a broader concept of son'eki sōsaiteki chōsei (an adjustment similar to a set-off of benefits). The latter is often used when considering whether benefits received by a victim or their heirs from third-party sources, like insurance payouts, should be deducted from tort damages.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Life Insurance is Not Deducted

The Supreme Court dismissed Y company's appeal, upholding the High Court's decision not to deduct the life insurance proceeds. The Court's reasoning was concise but definitive:

"Life insurance benefits paid based on a life insurance contract, by their nature, constitute consideration for premiums already paid, and are fundamentally payable irrespective of the cause of the tortious act. Therefore, even if, as in this case, the insured's death due to a tortious act results in the payment of insurance benefits to their heirs, X1 and X2, there is no basis for these benefits to be deducted from the amount of damages arising from the tortious act. It is appropriate to so interpret."

In essence, the Supreme Court found that life insurance payouts are a separate matter, stemming from a private contract financed by the insured or policyholder, and are not a "windfall" that should reduce the tortfeasor's liability.

Why Life Insurance Differs from Indemnity Insurance (e.g., Property Insurance)

The Supreme Court's decision to treat life insurance proceeds differently from benefits that might be subject to deduction in other contexts (particularly in relation to indemnity insurance, like property insurance) is significant. The rationale for this distinction involves several interrelated points:

1. Nature of the Benefit – Not Strictly Indemnification:

The Court emphasized that life insurance benefits are payable "irrespective of the cause of the tort." This is often interpreted to mean that life insurance, unlike property insurance which aims to indemnify (make whole) a specific, measurable financial loss, provides a pre-agreed, fixed sum upon the occurrence of death. This fixed-sum nature is characteristic of personal insurance. A 1995 Supreme Court decision concerning a fixed-sum passenger personal accident insurance policy similarly denied deduction from tort damages, reasoning that such insurance "does not have the nature of indemnifying the damage suffered by the insured." While some scholars argue that life insurance does serve an indemnification function (e.g., replacing lost income for dependents), the prevailing view in this line of cases is that its primary purpose is not a direct, itemized reimbursement of loss in the way indemnity insurance operates.

2. Absence of Insurer's Subrogation Rights in Life Insurance:

A crucial difference lies in the concept of insurer's subrogation. In indemnity insurance (e.g., fire insurance for a building), if an insurer pays the policyholder for damage caused by a third-party tortfeasor, the insurer typically "steps into the shoes" of the insured (is subrogated) and acquires the right to sue the tortfeasor for the amount it paid. This prevents the insured from recovering twice (once from the insurer, once from the tortfeasor) and ensures that the tortfeasor ultimately bears the cost of the damage.

Life insurance (and other forms of personal insurance) in Japan generally does not feature insurer subrogation (see Insurance Act, Article 25, which primarily applies to indemnity insurance). The absence of this subrogation mechanism for life insurance is sometimes cited as a reason why the law permits what might appear to be a "double recovery" by the beneficiaries (full insurance proceeds plus full tort damages). If the insurer cannot recover from the tortfeasor, and the beneficiaries cannot keep both, then the tortfeasor would effectively benefit from the victim's foresight in having insurance. The question then arises: why is subrogation generally absent in life insurance? One prominent view is that it's due to the inherent difficulties in precisely quantifying the "loss" in human life cases and the societal undesirability of strictly enforcing an "actual loss" indemnification principle in such sensitive matters.

3. The "Three Models" of Handling Insurance Benefits and Tort Damages:

When considering how insurance payouts intersect with tort damages, legal systems often implicitly or explicitly follow one of three broad models:

* Model 1: Duplicative Recovery (重複型 - jūfuku-gata): The victim or their heirs receive the full insurance payout AND the full amount of damages from the tortfeasor. The Supreme Court's 1964 decision effectively places life insurance in this category.

* Model 2: Subrogation-Deduction Type (代位控除型 - daikōjo-gata): The victim/heirs receive the insurance payout. They can then claim damages from the tortfeasor, but only for the amount exceeding the insurance payout. The insurer, through subrogation, claims the amount it paid from the tortfeasor. The net result is that the victim/heirs are made whole, and the tortfeasor pays the full amount of damages (part to the victim/heirs, part to the insurer). This is typical for indemnity insurance.

* Model 3: Tortfeasor Exemption Type (加害者免責型 - kagaisha menseki-gata): The victim/heirs receive the insurance payout. They can claim damages from the tortfeasor only for the amount exceeding the insurance payout. However, the insurer does not have a right of subrogation against the tortfeasor. In this model, the tortfeasor's total liability is effectively reduced by the amount of the insurance.

From the perspective of the victim/heirs, both Model 2 and Model 3 involve an "adjustment similar to set-off of benefits" because their direct claim against the tortfeasor is reduced. However, the tortfeasor's total financial burden is only reduced under Model 3.

Debating the Rationale

The Supreme Court's reasoning in the 1964 case has been subject to considerable academic discussion:

- "Consideration for Premiums": The judgment mentions that life insurance benefits are "consideration for premiums already paid." While factually correct, critics point out that this is also true for indemnity insurance, so it doesn't, by itself, explain the different treatment regarding deduction from tort damages.

- Policyholder's Intent: Perhaps the most compelling justification for not deducting life insurance proceeds is rooted in the presumed intent of the policyholder. It is widely argued that individuals take out life insurance with the intention of providing an additional financial resource for their beneficiaries, over and above any compensation they might receive from other sources, such as a tort claim. Deducting the life insurance payout from tort damages would frustrate this intent, effectively allowing the tortfeasor to benefit from the victim's prudence and premium payments. This view suggests that the "collateral source rule" (a principle in some legal systems that tort damages are not reduced by benefits received by the injured party from sources independent of the wrongdoer) finds a parallel here. It is also noted that if a policyholder had a demonstrably different intent (e.g., for the insurance to specifically offset tortfeasor liability), the outcome might theoretically differ, though this is rarely the case.

- Maintaining Tortfeasor Liability: An underlying normative principle is that a tortfeasor should be fully responsible for the harm they have caused and should not have their liability reduced because their victim was insured. While the subrogation model (Type 2) also achieves this by ensuring the tortfeasor pays the full amount (just to different parties), the no-deduction rule for life insurance (Type 1) directly benefits the victim's heirs while still holding the tortfeasor fully accountable.

Significance of the Ruling

The 1964 Supreme Court decision established a vital and enduring precedent in Japanese law:

- It clarified that life insurance proceeds received by the heirs of a tort victim are generally not to be deducted from the damages awarded against the tortfeasor. This allows for what is effectively a "duplicative recovery" from the perspective of the beneficiaries receiving both payments.

- The ruling underscores a fundamental distinction in the legal treatment of life insurance (as a form of personal, often fixed-sum, insurance) and non-life (indemnity) insurance when interacting with tort damages.

- It implicitly supports the idea that life insurance is often intended by the policyholder to be an independent source of financial support for beneficiaries, distinct from any legal claims arising from wrongful death.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 1964 judgment prioritizes the nature of the life insurance contract as a private agreement funded by premiums, with benefits intended for the designated beneficiaries, largely independent of the circumstances of a tort that might cause the insured's death. By ruling against the deduction of life insurance proceeds from tort damages, the Court ensured that the financial planning and security sought through life insurance are not diminished by the wrongful acts of third parties. Crucially, this also means that the tortfeasor does not indirectly benefit from the victim's foresight in securing life insurance for their loved ones. The decision reflects a policy choice to allow beneficiaries to receive the full benefit of both the insurance contract and any tort recovery, reinforcing the distinct purposes these two forms of compensation serve.