Life, Death, and the Law: A Japanese Supreme Court Case on Withdrawing Medical Treatment and Homicide

Date of Decision: December 7, 2009, Supreme Court of Japan (Third Petty Bench)

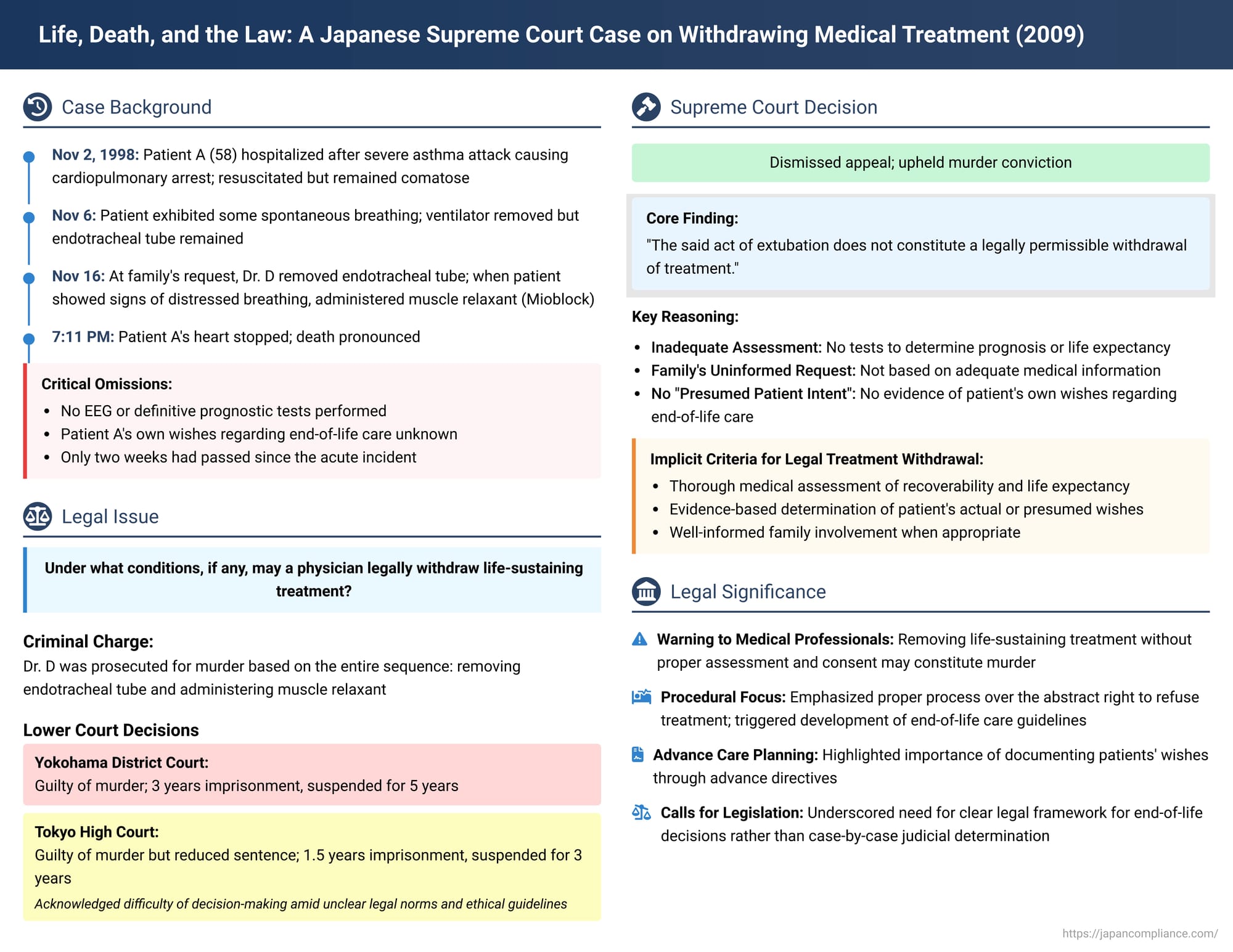

End-of-life medical decisions, particularly the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment, reside at a complex intersection of medical ethics, patient autonomy, family wishes, and the law. In Japan, where clear legislative guidelines on this issue have been sparse, medical professionals can find themselves in perilous legal territory. A landmark Supreme Court decision on December 7, 2009, starkly illustrated these challenges, upholding a murder conviction against a doctor who, at the request of a comatose patient's family, removed an endotracheal tube and subsequently administered a muscle relaxant. This case has been pivotal in discussions surrounding end-of-life care in Japan.

The Facts: A Patient in Coma, A Family's Plea, A Doctor's Actions

The case involved Patient A, a 58-year-old man, who was rushed to a hospital on November 2, 1998, after suffering a severe asthma attack that led to cardiopulmonary arrest. He was successfully resuscitated, but his consciousness did not return, and he remained in a comatose state until his death. The defendant, Dr. D, was the head of the hospital's respiratory medicine department and had been Patient A's attending physician since around 1985.

Initial Medical Management and Family Discussions:

- On November 4, 1998, Dr. D explained to Patient A's family that recovery of consciousness was unlikely and there was a high probability he would remain in a vegetative state.

- By November 6, Patient A exhibited some spontaneous breathing, and the mechanical ventilator was removed. However, an endotracheal tube remained in place to maintain an open airway by preventing tongue collapse and allowing for the suctioning of sputum.

- On November 12, Dr. D moved Patient A from the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) to a private room in a general ward. He instructed the nursing staff to reduce the patient's oxygen supply and IV fluid levels. He also communicated a "do not resuscitate" (DNR) policy to be followed in the event of a sudden deterioration in Patient A's condition.

- On November 13, Dr. D informed Patient A's wife about the move to the general ward, explaining that this transfer increased the risk of sudden, adverse changes in his condition, and he reconfirmed the DNR policy with her.

Critical Omissions and Unknown Patient Wishes:

A crucial aspect of the case was that between Patient A's admission and the eventual removal of the endotracheal tube, no electroencephalogram (EEG) or other tests considered necessary to definitively determine his prognosis or life expectancy were performed. Furthermore, Patient A's own views or wishes regarding end-of-life medical care were unknown.

The Tube Removal Incident on November 16, 1998:

- In the afternoon, Patient A's wife met with Dr. D and conveyed the family's collective decision. She reportedly said, "We've all thought about it, so we want you to remove the tube. We're all gathering tonight, so please do it today". Based on this request, Dr. D resolved to remove the tube.

- Around 6:00 PM, with Patient A's family gathered in his room, Dr. D, acknowledging that Patient A would likely die as a result, removed the endotracheal tube. He took no further measures to secure Patient A's airway. The family, at this point, had reportedly given up hope for Patient A's recovery.

- Unexpectedly, Patient A did not pass away quietly. Instead, he began to exhibit signs of severely labored and distressed breathing (agonal respiration), including arching his body.

- Dr. D attempted to alleviate this by administering sedatives (such as diazepam and midazolam) intravenously, but these measures failed to calm the patient's breathing.

- Dr. D then sought advice from a medical colleague, who suggested the use of a muscle relaxant. Dr. D obtained Mioblock (pancuronium bromide, a neuromuscular blocking agent) from the ICU's nursing station.

- Around 7:00 PM, Dr. D instructed a practical nurse to administer three ampules of Mioblock to Patient A via intravenous injection.

- Patient A's breathing stopped at approximately 7:03 PM, and his heart stopped at approximately 7:11 PM.

The Legal Battle: Murder Charges and Lower Court Rulings

Dr. D was subsequently prosecuted for murder, with the charge encompassing the entire sequence of actions from the removal of the endotracheal tube to the administration of Mioblock.

- Trial Court (Yokohama District Court): Found Dr. D guilty of murder. The court emphasized the lack of a definitive prognosis for Patient A, the fact that the family's request was made without adequate medical information, and the inability to confirm that the withdrawal was in line with Patient A's presumed intent. Dr. D was sentenced to three years in prison, with a five-year suspended execution of sentence.

- High Court (Tokyo High Court): Also found Dr. D guilty of murder. However, the High Court considered the sentence imposed by the trial court to be unduly harsh. It acknowledged that Dr. D was compelled to make a difficult decision in response to the family's strong request, particularly in a context where established legal norms and medical ethics regarding the withdrawal of treatment were lacking in Japan. Consequently, the High Court reduced the sentence to the then-minimum legal penalty for murder: one year and six months in prison, with a three-year suspended execution of sentence.

Dr. D's defense team appealed this decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision (December 7, 2009)

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, dismissed Dr. D's appeal, thereby affirming his conviction for murder.

Core Reasoning: Tube Removal Not Legally Permissible Treatment Withdrawal

The Supreme Court focused on the legality of the initial act of removing the endotracheal tube. Its key findings were:

- Inadequate Prognostic Assessment: No EEG or other necessary tests to determine Patient A's prognosis or life expectancy had been conducted prior to the tube removal. Only two weeks had passed since the acute asthma attack, which the Court deemed insufficient time to make an accurate judgment about recoverability or life expectancy.

- Family's Request Based on Insufficient Information: Patient A was in a comatose state. The family's request for tube removal, while stemming from their perception that Patient A's recovery was hopeless, was made in a situation where they had not been provided with adequate and objective medical information about his condition and potential prognosis.

- Lack of "Presumed Patient Intent": Crucially, the Court stated that the act of removing the tube could not be justified as being based on Patient A's "presumed intent" (推定的意思 - suitei teki ishi). There was no evidence of Patient A's own wishes regarding end-of-life care.

- Conclusion on Tube Removal: Based on these points, the Supreme Court concluded that "the said act of extubation does not constitute a legally permissible withdrawal of treatment".

Affirmation of Homicide:

Since the initial act of removing the endotracheal tube was deemed unlawful, the Supreme Court upheld the High Court's judgment that this act, combined with the subsequent administration of Mioblock, together constituted the act of murder.

Unpacking "Legally Permissible Treatment Withdrawal" – Insights and Unanswered Questions

This Supreme Court decision was the first by Japan's highest court to directly address the withdrawal of medical treatment in such a context. While it did not establish general, explicit criteria for when treatment withdrawal is legally permissible, its reasoning provided important, albeit implicit, pointers.

- SC's Implicit Factors: The Court's emphasis on the lack of adequate assessment of Patient A's "recoverability and life expectancy" and its finding that the family's request was not based on sufficient information nor on the patient's "presumed intent" strongly suggests that these are critical considerations for any legally defensible withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment. However, the judgment did not elaborate on how these factors should be weighed or how "presumed intent" should be ascertained, nor did it articulate an underlying legal principle (e.g., patient autonomy, medical futility) that would justify permissible withdrawal.

- The Trial Court's Framework: The first-instance court had drawn upon principles discussed in another well-known Japanese end-of-life case, the Tokai University Hospital euthanasia case. It had articulated two potential grounds for permissible treatment withdrawal:

- Patient's Right to Self-Determination: Where a patient's wishes are not explicitly known (e.g., due to unconsciousness), their "presumed intent" might be inferred, often with input from close family members. However, this process should be guided by the principle of "in dubio pro vita" (when in doubt, err on the side of life), with a general duty for physicians to prioritize life-sustaining measures.

- Objective Limits to the Doctor's Duty to Treat: This approach suggests that if medical treatment becomes objectively futile or even harmful to the patient, there is no legal obligation for the physician to continue it, regardless of any expressed patient wishes (or lack thereof) for its continuation. The trial court seemed to view these as independent justifications, where self-determination might allow for withdrawal at an earlier stage than purely objective medical futility.

The trial court also refined the patient condition requirement, moving from the Tokai case's "incurable disease, no hope of recovery, death inevitable and in its terminal stages" to "irrecoverable and death is imminent," requiring confirmation by multiple physicians and adherence to the "in dubio pro vita" principle.

- The High Court's Critique and Call for Legislation: The appellate High Court, while also convicting Dr. D, was critical of the existing legal ambiguity and the frameworks proposed by the trial court.

- It questioned the constitutional underpinnings of a patient's "right to refuse" life-sustaining treatment, particularly in light of Japanese Penal Code Article 202, which criminalizes participation in suicide and homicide by consent. It referenced a Supreme Court decision on a Jehovah's Witness patient's refusal of blood transfusion, where the right was framed as an aspect of "personality rights" rather than a broad "right to self-determination".

- The High Court expressed skepticism about relying on family members to determine a patient's "presumed intent," warning that families' own interests (e.g., relief from financial or emotional burdens) might unduly influence their judgment, making it more a reflection of the family's wishes than the patient's. It also suggested that trying to estimate an unconscious patient's wishes often borders on "fiction".

- Regarding the "limits of the duty to treat" argument, the High Court felt it applied too narrowly, essentially only to situations akin to brain death where treatment is truly medically meaningless, and thus did not adequately cover the broader spectrum of end-of-life scenarios where "death with dignity" might be sought.

- Ultimately, the High Court concluded that a fundamental resolution of the "death with dignity" issue requires the enactment of specific legislation or, at a minimum, comprehensive, authoritative guidelines. It emphasized the need for clear procedural safeguards, not just substantive criteria, and deemed the problem too profound for the judiciary to resolve comprehensively on its own.

The Aftermath: The Ongoing Quest for Clarity in End-of-Life Care in Japan

The Supreme Court's 2009 decision, by convicting Dr. D of murder, sent a strong message about the legal risks physicians face in Japan when making end-of-life decisions in the absence of clear legal and societal consensus. While the judgment itself did not lay down general rules for permissible treatment withdrawal, it powerfully highlighted the necessity of:

- Thorough Medical Assessment: A rigorous evaluation of the patient's condition, including prognosis and potential for recovery, using all appropriate diagnostic tools.

- Ascertaining Patient Wishes: A genuine effort to determine the patient's own wishes regarding end-of-life care, either through prior expressions or, if that is not possible, through a carefully considered process of determining presumed intent, based on adequate information.

- Informed Family Involvement: Ensuring that any family requests are based on a full and accurate understanding of the patient's medical situation and prospects.

In the years following this decision, there has been continued debate and development in Japan regarding end-of-life care:

- Development of Guidelines: The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, along with various medical societies, has issued several sets of guidelines concerning medical decision-making processes at the end of life. While these guidelines are not legally binding in the same way as statutes, they aim to provide ethical and procedural frameworks for healthcare professionals.

- Emphasis on Advance Care Planning (ACP): There is a growing recognition of the importance of Advance Care Planning, encouraging individuals to discuss and document their wishes for future medical care, including end-of-life preferences, through tools like advance directives.

- Persistent Challenges: Despite these developments, significant challenges remain. These include defining "medical futility" in a consistent manner, clarifying the precise role and legal standing of family members in decision-making for incapacitated patients, and operationalizing the concept of the "patient's best interests" when their specific wishes are unknown.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2009 decision in the case of Dr. D and Patient A was a watershed moment in Japanese medicolegal history. By upholding a murder conviction against a physician for withdrawing treatment under circumstances deemed medically and procedurally inadequate, the Court underscored the grave legal jeopardy involved in end-of-life decisions made without a clear legal mandate or adherence to rigorous standards of assessment and consent (or presumed intent).

While the judgment did not provide the comprehensive legal framework many had hoped for, it critically highlighted the deficiencies in the existing system and implicitly pointed towards essential considerations for any future legal or ethical guidelines: meticulous medical evaluation, respect for patient autonomy (including presumed intent when directly expressed wishes are absent), and transparent, informed involvement of family. The case has undoubtedly fueled the ongoing societal and professional discourse in Japan aimed at establishing clearer, more humane, and legally sound approaches to care at the end of life.