Licensing Trade Secrets and Data in Japan: Navigating the Risks to Licensee Rights

Understand Japan's legal gaps that leave trade secret and data licensees exposed in M&A or bankruptcy—and practical steps to mitigate the risks.

TL;DR

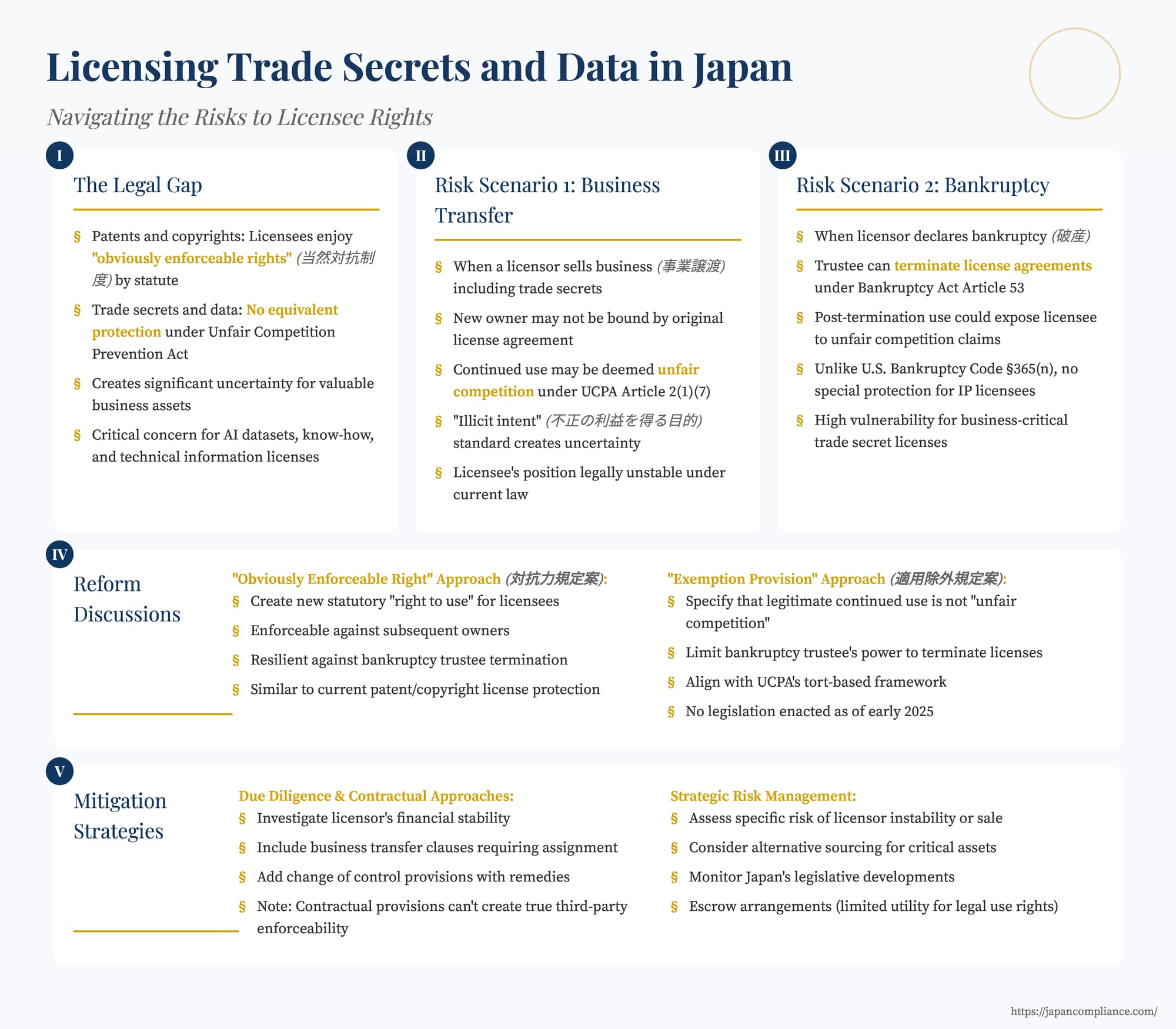

Japan’s Unfair Competition Prevention Act safeguards trade secrets themselves but gives licensees little statutory protection if a licensor sells its business or goes bankrupt. Until reform arrives, parties must rely on due‑diligence, successor‑assumption clauses, and contingency planning.

Table of Contents

- Why Licensee Protection is a Critical Concern

- The Current Legal Gap: Trade Secrets and Data vs. Other IP

- Risks Illustrated: Potential Pitfalls for Licensees in Japan

- The Drive for Reform: Legislative Discussions in Japan

- Practical Implications and Mitigation Strategies for US Businesses

- Conclusion: Awareness and Vigilance Required

For US businesses, licensing intellectual property is a cornerstone of international strategy, whether it's acquiring critical know-how, accessing valuable datasets for AI development, or distributing software. When licensing trade secrets or proprietary data from Japanese entities, or allowing Japanese licensees to use your company's valuable information, understanding the robustness of licensee rights under Japanese law is paramount.

While Japan offers strong protection for trade secrets themselves under the Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA), the legal standing of a licensee of trade secrets or "limitedly provided data" (限定提供データ - gentei teikyo data, a category of valuable business data protected under the UCPA) faces significant uncertainties, particularly if the licensor undergoes a change of ownership or faces insolvency. This contrasts with the clearer protections afforded to licensees of other IP rights like patents and copyrights in Japan.

This article explores the current legal landscape for licensees of trade secrets and data in Japan, the potential risks, and ongoing discussions for reform.

Why Licensee Protection is a Critical Concern

Businesses increasingly rely on licensing to access and leverage valuable intangible assets. Common scenarios include:

- Know-How Licensing: Often bundled with patent licenses, know-how or trade secret licenses provide access to essential unpatented technical information, manufacturing processes, or formulas crucial for effectively using patented technology.

- Data Licensing: The rise of big data analytics, IoT, and AI has spurred a market for licensing large datasets, such as industrial operational data from sensors, consumer behavior data, or curated datasets for training AI models.

- Franchising and Distribution: Franchise agreements often involve the transfer of significant operational trade secrets and business methods.

For the licensee, the continuity of these license rights is often critical for their business operations, product development, and return on investment. If the right to use the licensed trade secret or data is suddenly terminated or becomes unenforceable against a new owner of that information, the licensee's business can suffer severe disruption and financial loss.

The Current Legal Gap: Trade Secrets and Data vs. Other IP

A key point of reference is how Japanese law treats licensees of other forms of intellectual property. For patents, copyrights, and trademarks, Japan has systems that provide what is often termed an "obviously enforceable right" or "automatic perfection" (当然対抗制度 - touzen taikou seido).

- Patents: Under Article 99 of the Patent Act, a non-exclusive licensee (通常実施権者 - tsuujou jisshikensha) whose license was granted by the patent holder or an exclusive licensee generally can assert their license rights against anyone who subsequently acquires the patent or an exclusive license, even without registration of the non-exclusive license.

- Copyrights: Similarly, Article 63-2 of the Copyright Act, following a 2020 amendment, provides that a licensee of a copyright can assert their license rights against a subsequent transferee of the copyright or a pledgee, without needing to register the license.

These provisions mean that if a patent or copyright is sold, or the owner goes bankrupt, the legitimate licensee can typically continue to use the IP under the terms of their license.

However, the Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA), which is the primary law governing the protection and misappropriation of trade secrets and limitedly provided data, currently lacks any equivalent explicit statutory protection for licensees of these assets. This silence in the law creates significant ambiguity and risk.

Risks Illustrated: Potential Pitfalls for Licensees in Japan

The absence of clear statutory protection for trade secret and data licensees under the UCPA can lead to precarious situations, especially in two common scenarios: the licensor's business is sold, or the licensor goes bankrupt.

Scenario 1: Licensor's Business (including the Trade Secret/Data) is Sold (事業譲渡 - jigyou jouto)

Imagine a US company (Licensee Y) has a valid license to use a trade secret from a Japanese company (Licensor A). Licensor A then sells its entire business, including the trade secret, to another company (New Owner X).

- Can New Owner X stop Licensee Y from using the trade secret? This is where the uncertainty lies.

- Licensee Y's contractual right was with Licensor A. New Owner X is not a party to that original license.

- New Owner X might argue that Licensee Y's continued use, without X's permission, constitutes an act of unfair competition. Specifically, they might point to UCPA Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 7. This provision covers situations where a person who was legitimately shown a trade secret (e.g., an employee or original licensee) subsequently uses or discloses it for an illicit purpose (like unfair competition or harming the new owner) or beyond the scope of their original authorization (which effectively ceased with the transfer to X if the license isn't assumed).

- To establish unfair competition under Item 7, "illicit intent" (不正の利益を得る目的、又はその営業秘密保有者に損害を加える目的 - fusei no rieki o eru mokuteki, matawa sono eigyou himitsu hoyuusha ni songai o kuwaeru mokuteki) is typically required. Whether a licensee merely continuing to operate under a previously valid license demonstrates such intent is debatable and fact-dependent.

- Defenses for the licensee, such as claiming they were a bona fide acquirer of the information (UCPA Article 19, Paragraph 1, Item 6, which provides an exception for those who acquire a trade secret without knowledge of prior misappropriation and without gross negligence), are often difficult to apply in this context because the licensee originally acquired the information legitimately from Licensor A, not through a chain of misappropriation. The issue is whether their continued use becomes unauthorized after the transfer.

Japanese legal commentary suggests that in such business transfer scenarios, the licensee's position is legally unstable due to the lack of a clear "obviously enforceable right."

Scenario 2: Licensor Goes Bankrupt (破産 - hasan)

Consider the same license agreement. This time, Licensor A declares bankruptcy. A bankruptcy trustee is appointed to manage A's assets.

- Can the bankruptcy trustee terminate the license agreement and stop Licensee Y's use?

- Under Japan's Bankruptcy Act (破産法 - Hasan Hou), Article 53, Paragraph 1 gives the trustee the power to either assume or terminate bilateral executory contracts (contracts where both parties still have outstanding obligations). A trade secret or data license, where the licensor has an ongoing obligation to permit use and the licensee to pay royalties or adhere to terms, would likely be considered such a contract.

- If the trustee terminates the license, Licensee Y loses its contractual basis to use the trade secret or data.

- Continued use by Licensee Y post-termination could again expose it to claims of unfair competition from the bankruptcy estate (as the new controller of the trade secret). The "illicit intent" and bona fide acquisition arguments would surface similarly to the business transfer scenario, with similarly uncertain outcomes for the licensee.

Again, the consensus among legal experts in Japan is that, without specific statutory protection, the licensee's ability to continue using the trade secret or data after the licensor's bankruptcy is highly vulnerable.

The Drive for Reform: Legislative Discussions in Japan

The precarious legal position of trade secret and data licensees has not gone unnoticed in Japan. Recognizing the increasing importance of know-how and data licensing for innovation and economic activity (e.g., for IoT, AI, and open innovation initiatives), there have been official discussions within governmental bodies like METI subcommittees about the need to establish a more robust protection system for these licensees.

The primary goal is to provide licensees with greater legal stability and predictability, thereby encouraging the licensing and utilization of these valuable intangible assets. Two main approaches have been prominent in these discussions:

- "Obviously Enforceable Right" Approach (対抗力規定案 - taikouryoku kitei an):

- This approach would involve amending the UCPA to create a new statutory "right to use" (or a similar legal status) for legitimate licensees of trade secrets and limitedly provided data.

- This "right to use" would be, by its nature, enforceable against third parties who subsequently acquire the trade secret/data (e.g., a new business owner) and would be resilient against termination by a bankruptcy trustee, similar to how patent and copyright licenses are treated.

- Arguments for this approach include harmonization with other IP laws in Japan and providing the strongest, clearest form of protection for licensees.

- "Exemption Provision" Approach (適用除外規定案 - tekiyou jogai kitei an):

- This approach would focus on amending the UCPA to specifically state that legitimate continued use of a trade secret or data by a licensee, following a business transfer or licensor bankruptcy (where the license might otherwise be deemed terminated), does not constitute an act of unfair competition under defined circumstances.

- It might also involve amending Article 53 of the Bankruptcy Act to limit the trustee's power to terminate such licenses if it would be unduly detrimental to the licensee and the continuation is not overly burdensome to the bankruptcy estate.

- Arguments for this approach suggest it might better align with the UCPA's traditional structure as a law regulating "unfair acts" (a tort-based framework) rather than creating new proprietary-like rights. However, some express concern that this approach might be less comprehensive or could, depending on drafting, overly strengthen licensee rights beyond what is balanced.

As of early 2025, while these discussions have been ongoing and the need for reform is acknowledged, specific legislation creating such protections for trade secret and data licensees has not yet been enacted. The amendments to the UCPA in 2023 (effective 2024) focused on other areas like damages, burden of proof, and international jurisdiction. Therefore, the legal uncertainty for these licensees largely remains.

Practical Implications and Mitigation Strategies for US Businesses

Given the current legal landscape in Japan, US companies entering into or relying on trade secret or data licenses with Japanese counterparts, or licensing their own such assets into Japan, should be aware of these risks and consider potential mitigation strategies:

- Thorough Due Diligence:

- Before entering into a license, especially as a licensee, conduct due diligence on the licensor's financial stability and business prospects.

- Understand the ownership structure of the IP and any encumbrances.

- Careful Contractual Drafting (Acknowledging Limitations):

- While contractual clauses cannot create true "obviously enforceable rights" against third parties or bankruptcy trustees where the statute doesn't provide for them, they can still offer some level of protection or clarity between the contracting parties:

- Business Transfer Clauses: Include clauses requiring the licensor to obligate any successor-in-interest (new owner of the business/secret) to assume the license agreement on the same terms. While enforceability against a non-assuming new owner is the core problem, this places a clear obligation on the original licensor.

- Change of Control Provisions: These might give the licensee certain rights (e.g., termination, modified terms, or even a claim for damages against the original licensor) if the licensor undergoes a change of control that jeopardizes the license.

- Bankruptcy Provisions: Attempting to stipulate that the license cannot be terminated in bankruptcy is unlikely to override the trustee's statutory powers under Article 53. However, clauses addressing continued use post-termination (perhaps with a transition period or a separate, nominal consideration) might be attempted, though their enforceability would be highly questionable.

- Governing Law and Dispute Resolution: While Japanese law will likely govern the UCPA aspects and bankruptcy within Japan, ensure the contract's general governing law and dispute resolution clauses (e.g., arbitration in a neutral venue) are favorable for resolving contractual breaches by the licensor.

- While contractual clauses cannot create true "obviously enforceable rights" against third parties or bankruptcy trustees where the statute doesn't provide for them, they can still offer some level of protection or clarity between the contracting parties:

- Strategic Risk Assessment:

- For critical licenses where disruption would be catastrophic, assess the specific risk of licensor instability or business sale.

- Consider the value of the licensed asset and the investment made in reliance on the license.

- Explore alternative sourcing or parallel development if the risk is deemed too high and the licensed asset is absolutely core to your Japanese operations.

- Source Code/Data Escrow (Limited Utility for Use Rights):

- While more common for software source code, escrow arrangements ensure access to the material if the licensor fails to support it. However, this doesn't inherently grant the legal right to continue using a trade secret or data if the license right itself is terminated or lost against a new owner. Its utility is more for maintenance and understanding, not necessarily continued commercial exploitation rights.

Conclusion: Awareness and Vigilance Required

The current Japanese legal framework presents a notable vulnerability for licensees of trade secrets and limitedly provided data when compared to licensees of patents or copyrights. The absence of an explicit "obviously enforceable right" means that such licensees face considerable uncertainty and risk if their licensor sells the relevant business or becomes insolvent.

For US companies, awareness of this legal gap is the first step. While contractual clauses can attempt to mitigate some risks between the direct parties, they cannot fully substitute for statutory third-party enforceability or protection in bankruptcy. Therefore, when negotiating and managing licenses for these critical intangible assets in Japan, a heightened level of due diligence, careful risk assessment, and strategic contractual drafting is essential. Furthermore, US businesses should continue to monitor legislative developments in Japan, as there is a recognized need and ongoing discussion for reforms that could significantly improve the position of trade secret and data licensees in the future.

- Protecting Your IP in Japan: Strategies for Patents, Trademarks, and Copyright

- Disclosed Your Invention Before Filing in Japan? Understanding Japan's Grace Period for Novelty

- How Does Japan's Anti‑Monopoly Act Impact M&A Transactions?

- Unfair Competition Prevention Act – English Translation (Cabinet Office)

- Outline of the Unfair Competition Prevention Act – METI