Licensing Data in Japan: Intellectual Property Considerations and Protection Strategies

TL;DR

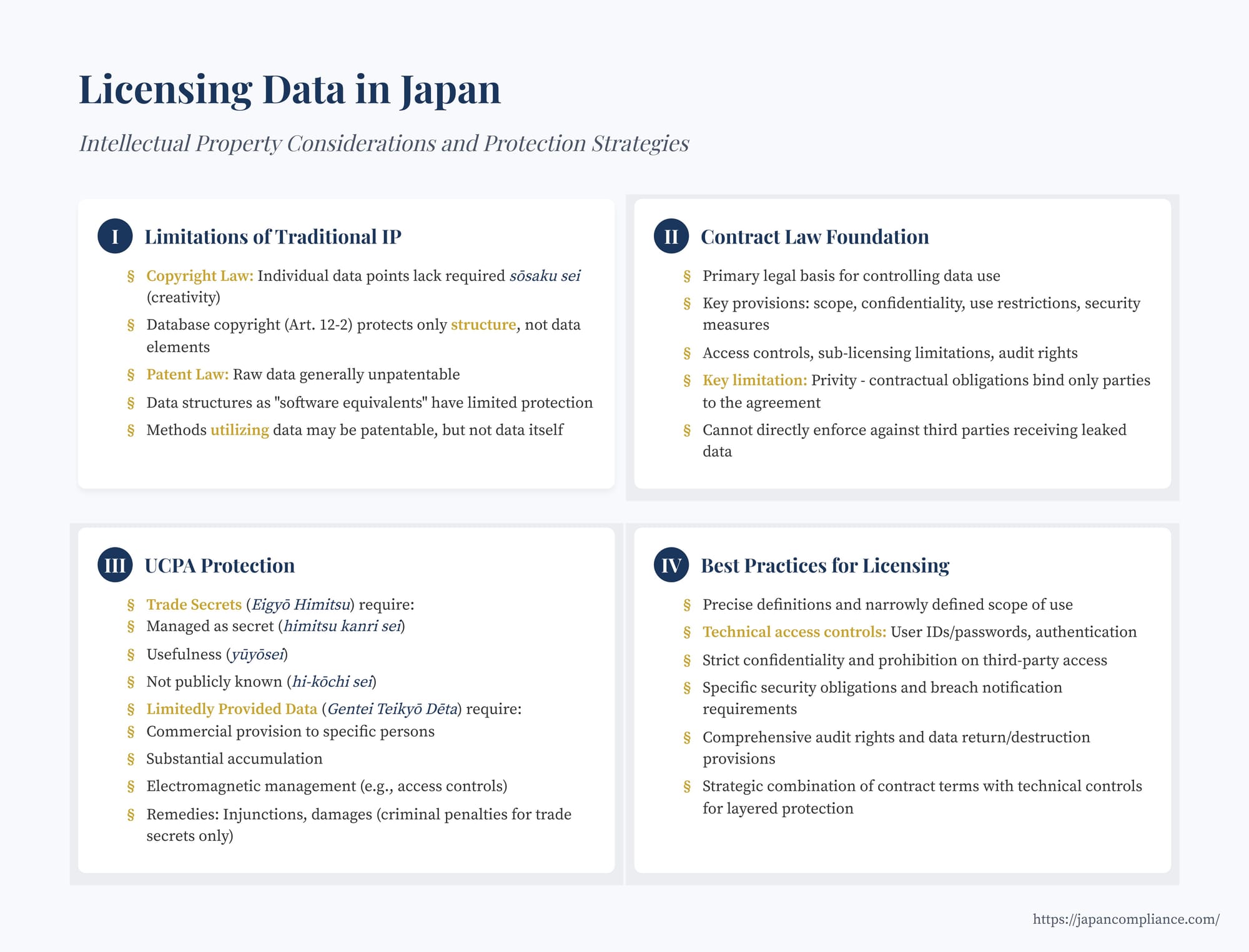

Japanese copyright and patent laws rarely cover raw datasets, so data-licensing relies on contracts plus the Unfair Competition Prevention Act. Trade-secret rules help when data remains confidential, while the 2018 “Limitedly Provided Data” regime protects commercially shared datasets managed by login controls. Combine tight licence terms with technical access controls for solid protection.

Table of Contents

- Limitations of Traditional IP for Data Protection

- The Foundational Role (and Limits) of Contract Law

- Protection Under the Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA)

- Best Practices for Data Licensing Agreements in Japan

- Conclusion

In the modern "data-driven society" , data has transcended its role as mere information to become a critical corporate asset (情報資産, jōhō shisan). Businesses invest heavily in collecting, analyzing, and curating vast datasets for various purposes, from internal R&D and operational efficiency to developing AI models and personalizing customer experiences. Recognizing the immense value locked within these datasets, companies are increasingly exploring opportunities to license or share their data with third parties – partners, customers, researchers, or even competitors – often for significant fees or in exchange for reciprocal access.

However, sharing valuable data inherently carries risks. Once data leaves the originator's direct control, preventing unauthorized use, disclosure, or further dissemination becomes a significant challenge. This necessitates robust legal frameworks and carefully crafted agreements to protect the data provider's investment and maintain control over their valuable information assets.

This article explores the legal landscape for protecting and licensing data in Japan. It examines the limitations of traditional intellectual property (IP) laws like copyright and patent, the foundational role of contract law, and the crucial supplementary protections offered by Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA), particularly its provisions on trade secrets and the relatively new concept of "Limitedly Provided Data."

Limitations of Traditional IP for Data Protection

While copyright and patent laws are the cornerstones of IP protection for many creations, their applicability to raw data itself is often limited in Japan.

1. Copyright Law (著作権法, Chosakuken Hō)

- Data Points vs. Creative Works: Individual data points or factual information generally lack the necessary "creativity" (創作性, sōsaku sei) – the expression of an author's thoughts or feelings – required for copyright protection as literary, scientific, or other works under Article 2(1)(i) of the Copyright Act. Simple facts, measurements, or observations are typically not copyrightable subject matter.

- Database Copyright (データベースの著作物, dētabēsu no chosakubutsu): Article 12-2 of the Copyright Act does provide specific protection for databases, defined as "a collection of information such as theses, numerical data, figures and other forms of information, which is systematically constructed so that such information can be searched by using a computer." However, protection hinges on demonstrating creativity in the selection or systematic arrangement of the information within the database. Standard, comprehensive databases designed for broad utility often use commonplace structures or non-selective compilation methods, making it difficult to meet this creativity threshold. Critically, even if the database structure qualifies for copyright, this protection does not extend to the individual data elements themselves if they lack their own creativity. Unauthorized copying of the entire creative database structure could constitute infringement, but extracting and reusing the underlying (non-creative) data points typically does not infringe the database copyright.

- Limited Exceptions: While Article 30-4 allows for certain non-enjoyment uses of copyrighted works (including potentially data within a creative database) for purposes like information analysis (e.g., AI training) without permission, this provision does not authorize the subsequent commercial redistribution or unauthorized sale of the data or derivative datasets if it unreasonably prejudices the copyright holder's interests.

2. Patent Law (特許法, Tokkyo Hō)

- Data vs. Invention: Raw data itself is generally considered unpatentable. It falls outside the definition of a statutory invention, often viewed as mere presentation of information, abstract ideas, or mathematical discoveries.

- Data Structures as "Software Equivalents": Japanese Patent Office (JPO) examination guidelines acknowledge that data structures can, in some limited circumstances, be treated like computer programs ("software equivalents" - プログラムに準ずるもの) if the structure itself dictates or controls specific information processing by a computer. This might apply to highly specialized data formats designed to enable particular technical functions. However, this protection relates to the structure, not the underlying data content or values.

- Inventions Utilizing Data: While data itself isn't patentable, inventions that utilize data – such as novel AI algorithms trained on specific datasets, innovative data processing methods, or systems incorporating unique data analysis techniques – may be patentable if they meet the standard requirements of novelty, inventive step, and industrial applicability. The patent protects the application or method, not the data per se.

In summary, relying solely on traditional copyright or patent law to protect the value inherent in datasets, particularly factual or non-creative data, is generally insufficient in Japan.

The Foundational Role (and Limits) of Contract Law

Given the limitations of IP law, contracts form the primary legal basis for controlling the use and dissemination of licensed data. Data license agreements are essential for defining the rights and obligations of both the data provider (licensor) and the data recipient (licensee). Key contractual provisions typically include:

- Scope of License: Clearly defining the specific data being licensed, the permitted purposes of use (e.g., internal R&D only, specific project), the duration of the license, and any geographical restrictions.

- Confidentiality/Non-Disclosure: Obligating the licensee to keep the data confidential and not disclose it to unauthorized third parties.

- Use Restrictions: Prohibiting use beyond the licensed scope, reverse engineering (if applicable), modification, or combination with other data unless permitted.

- Security Measures: Requiring the licensee to implement reasonable technical and organizational security measures to protect the data from unauthorized access or breaches.

- Access Controls: Specifying methods like user IDs, passwords, encryption, or access logs, which are also relevant for potential UCPA protection (see below).

- Sub-licensing: Prohibiting or strictly controlling the licensee's ability to grant access to the data to other parties.

- Audit Rights: Allowing the licensor to audit the licensee's compliance with the agreement's terms.

- Data Return/Destruction: Mandating the return or secure destruction of all licensed data and copies upon termination or expiration of the license.

- Liability and Indemnity: Allocating responsibility for data breaches, misuse, or inaccuracies.

While crucial, contract law suffers from a fundamental limitation: privity. Contractual obligations only bind the parties who signed the agreement (the licensor and the licensee). If the licensee breaches the contract and improperly discloses the data to an unauthorized third party, the licensor generally cannot sue that third party directly for breach of contract. While the licensor can sue the licensee for breach, recovering the data or stopping its further spread by third parties through contract law alone is often difficult or impossible. This highlights the need for legal protections that extend beyond the direct contractual relationship.

Protection Under the Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA)

Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA - 不正競争防止法, Fusei Kyōsō Bōshi Hō) provides critical supplementary protection for valuable business information, including data, that falls outside the scope of traditional IP rights. It addresses specific acts of misappropriation and unfair competition. Two regimes under the UCPA are particularly relevant for data protection:

1. Trade Secrets (営業秘密, Eigyō Himitsu) (UCPA Art. 2(1)(iv)-(x))

Data can be protected as a trade secret if it meets three cumulative requirements (defined in Art. 2(6)):

- Managed as Secret (秘密管理性, himitsu kanri sei): The information must be kept secret through reasonable efforts by the holder. This requires objective measures demonstrating an intent to maintain secrecy, such as labeling documents "Confidential," implementing access controls, using NDAs with employees and third parties, etc. The level of measures required depends on the circumstances.

- Usefulness (有用性, yūyōsei): The information must be technically or commercially useful for business activities. This threshold is generally met by curated datasets used for R&D, customer lists, proprietary algorithms, etc.

- Not Publicly Known (非公知性, hi-kōchi sei): The information must not be generally known or easily ascertainable by the public or competitors through legitimate means.

If data qualifies as a trade secret, the UCPA prohibits various acts of misappropriation, including:

- Acquiring a trade secret by improper means (theft, fraud, coercion, hacking, etc.).

- Using or disclosing an improperly acquired trade secret.

- Disclosing a trade secret in breach of a legal duty of confidentiality (e.g., by an employee or contracting party bound by an NDA).

- Acquiring, using, or disclosing a trade secret while knowing (or being grossly negligent in not knowing) that it was previously acquired or disclosed improperly or in breach of duty.

Limitations for Licensed Data: While potentially applicable, relying on trade secret protection for licensed data can be challenging. The act of licensing itself involves disclosure to the licensee. While NDAs help maintain the "managed as secret" element vis-à-vis the licensee, widespread licensing can potentially erode the "not publicly known" requirement over time. Furthermore, if the licensor's primary goal is data sharing and use by licensees, rather than strict secrecy, demonstrating robust secret management measures might become more difficult. If data is licensed to many parties, even under confidentiality obligations, proving it remains "not publicly known" in the trade secret sense can be problematic.

2. Limitedly Provided Data (限定提供データ, Gentei Teikyō Dēta) (UCPA Art. 2(7), Art. 2(1)(xi)-(xvi))

Recognizing the gap in protecting commercially valuable data shared under controlled conditions but not meeting the stringent requirements of trade secrets, Japan amended the UCPA in 2018 to introduce protection for "Limitedly Provided Data." This regime is specifically designed for scenarios common in data licensing.

To qualify as Limitedly Provided Data under Article 2(7), information must meet three criteria:

- Provided Commercially to Specific Persons (業として特定の者に提供, gyō to shite tokutei no mono ni teikyō): The data must be provided as part of a business activity to specific, identifiable parties. This explicitly includes provision under paid licenses or data service agreements. Even if access is open to anyone who pays a fee and agrees to terms, those who do so can be considered "specific persons."

- Substantial Accumulation (相当量蓄積, sōtō ryō chikuseki): The data must be accumulated to a significant extent ("substantial volume"). This focuses on the value derived from the collection and aggregation of data, typical of valuable datasets used for analysis, AI training, etc. Whether the volume is "substantial" is judged based on whether it possesses value because of its electromagnetic accumulation, considering factors like the cost/effort of collection, analysis, and management, its potential for use, and market value.

- Electromagnetic Management (電磁的方法により管理, denji-teki hōhō ni yori kanri): The data must be managed electronically in a way that restricts access to the authorized recipients. This typically requires technical access controls, such as user IDs and passwords, encryption, or similar digital measures that objectively signal the provider's intent to limit access to specific licensees. Mere physical security around servers is insufficient.

Importantly, Article 2(7) explicitly excludes information that is "managed as secret" (i.e., trade secrets). The two regimes are mutually exclusive; Limitedly Provided Data protection applies where trade secret status cannot be established (often due to the broader, albeit controlled, sharing).

Acts constituting unfair competition with respect to Limitedly Provided Data (Art. 2(1)(xi)-(xvi)) include:

- Acquiring the data through improper means (hacking, unauthorized access) with the intent to cause harm to the provider's business (Art. 2(1)(xi)).

- Using or disclosing improperly acquired Limitedly Provided Data (Art. 2(1)(xii), (xiii)).

- Disclosing Limitedly Provided Data by an authorized recipient (licensee) in significant breach of their data management duties for the purpose of unfair commercial gain or causing harm (Art. 2(1)(xiv)).

- Using or further disclosing Limitedly Provided Data acquired from an authorized recipient (licensee) while knowing (or being grossly negligent in not knowing) about the subsequent improper disclosure (Art. 2(1)(xv), (xvi)).

Advantages for Licensed Data: This regime is well-suited for protecting datasets shared via online platforms or databases where licensees are granted access through login credentials but are expected to abide by usage restrictions. It directly addresses the risk of data leakage or misuse originating from an authorized licensee or through unauthorized access, without requiring the stringent secrecy levels of trade secret law. The requirement of "electromagnetic management" (access controls) aligns well with common data licensing practices.

Remedies: If data qualifies as Limitedly Provided Data and an act of unfair competition occurs, the data provider can seek civil remedies, including:

- Injunctions (差止請求, sashitome seikyū): To stop the unauthorized acquisition, use, or disclosure (UCPA Art. 3).

- Damages (損害賠償請求, songai baishō seikyū): To compensate for losses suffered due to the misappropriation (UCPA Art. 4). Measures to restore business reputation may also be available (UCPA Art. 14).

Unlike trade secrets, however, the misappropriation of Limitedly Provided Data is currently not subject to criminal penalties under the UCPA.

Best Practices for Data Licensing Agreements in Japan

To maximize protection when licensing data in Japan, agreements should be drafted carefully, integrating contractual protections with considerations for potential UCPA applicability (especially the Limitedly Provided Data regime):

- Precise Definitions: Clearly define the specific dataset(s) being licensed. Ambiguity can lead to disputes.

- Scope of Use: Narrowly define the permitted uses, purposes, duration, and territory. Prohibit any use outside this scope.

- Access Controls: Explicitly require the use of specific technical access controls (e.g., unique user IDs/passwords, multi-factor authentication) provided by the licensor. This reinforces the "electromagnetic management" requirement for potential Limitedly Provided Data protection.

- Confidentiality & Non-Disclosure: Include robust NDA clauses covering the data and potentially the terms of the agreement itself.

- Prohibition on Third-Party Access/Sub-licensing: Strictly forbid disclosure to, or access by, unauthorized third parties or any sub-licensing without explicit prior written consent.

- Security Obligations: Impose clear obligations on the licensee to maintain adequate technical and organizational security measures to protect the data, potentially referencing specific standards (e.g., ISO 27001).

- Breach Notification: Require prompt notification from the licensee in case of any suspected or actual data breach or unauthorized access/disclosure.

- Audit Rights: Include provisions allowing the licensor to audit the licensee's compliance with data handling and security obligations.

- Termination Rights & Data Return: Clearly define termination events (including breach) and mandate the secure return or certified destruction of all licensed data and copies upon termination.

- Liability & Indemnification: Carefully allocate liability for breaches of the agreement, data misuse, or third-party claims. Consider limitations of liability, but be mindful of restrictions under laws like the Consumer Contract Act if licensing to individuals.

- Governing Law & Dispute Resolution: Choose the governing law and dispute resolution forum (court or arbitration) strategically, considering enforceability against a Japanese licensee.

Combining strong contractual terms with robust technical access controls provides the most effective layered approach to protecting licensed data under Japanese law.

Conclusion

Protecting valuable data assets, especially when sharing them through licensing agreements, presents unique challenges that traditional IP laws in Japan only partially address. While copyright and patent offer limited direct protection for data content itself, contract law remains the foundational tool for defining the terms of use and imposing obligations on licensees. However, due to the principle of privity, contracts alone cannot prevent misappropriation by third parties.

This is where Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA) becomes crucial. While trade secret protection may apply to certain highly confidential datasets, its requirements can be difficult to maintain in licensing scenarios involving broader sharing. The Limitedly Provided Data regime, introduced in 2018, offers a more tailored and often more suitable avenue for protecting commercially shared datasets managed via electronic access controls. By understanding the specific requirements of this regime – commercial provision, substantial accumulation, and electromagnetic management – and aligning licensing practices accordingly (especially through strong contractual clauses and technical access controls), businesses can significantly enhance their ability to seek legal recourse